Zev Eleff

In June 1984, Rabbi Fabian Schonfeld told hundreds assembled at a Rabbinical Council of America convention that there were just a few differences between the Modern Orthodox and the Orthodox Right. “We are just as right wing as they are,” he announced. “There are two major differences: one is our total commitment to the State of Israel and the other is the area of the pursuit of secular knowledge which they at best tolerate as a last resort.”[1] Rabbi Schonfeld was in good company. Several years earlier, the RCA published an eighty-page symposium on the “State of Orthodoxy.” The sixteen participants covered many issues but the vast majority seemed to ignore, in the words of one vociferous critic, the “invisible majority,” namely, “Orthodox women.”[2] The sentiment was shared by other female (and some male) observers, who also conveyed a feeling of betrayal.[3]

Advances for Modern Orthodox Women

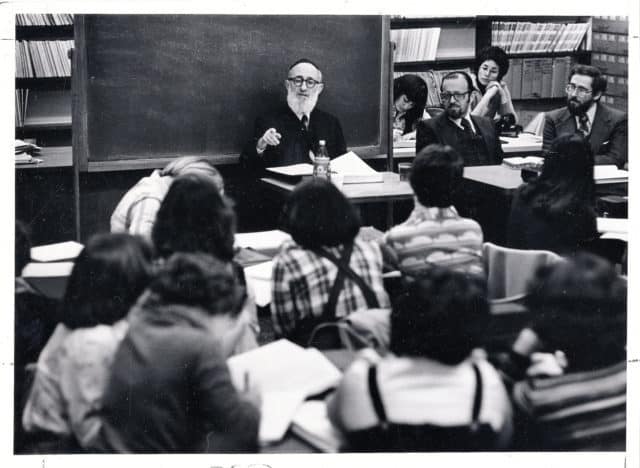

After all, the recent past had promised much to Modern Orthodox girls and women, particularly in the realms of advanced Torah study, prayer, and leadership. First, there were gains made in women’s Talmud. This was not altogether new. A handful of Orthodox day schools had implemented Talmud instruction for girls back in the 1940s. However, there was little traction and much resistance, particularly among the Orthodox Right. In January 1965, the Agudath Israel published a checklist to “help parents rate the institutions that seek to provide a Torah education for their children.” One item in the field of “Curriculum” read: “The boys’ curriculum leads to, and emphasizes Gemorah, and the girls’ curriculum excludes it.”[4] Momentum arrived in a big way in the late-1970s. On October 11, 1977, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik delivered the inaugural Talmud lecture at Stern College for Women. The newly minted Beit Midrash Program was meant to usher in a “new era in Jewish education.”[5] The Rav’s support should have solidified that, some believed. At the very least, one observer claimed, the “halakhic issue [had] been settled for the modern Orthodox community.”[6]

Second was the very vocal debates over the legitimacy of women’s prayer groups. Halakhic discussions and treatments on this form of semiformal worship—they omitted all parts of prayer that required a quorum—is substantial.[7] Those who spearheaded this effort were generally day school-educated women, very much part of the Modern Orthodox mainstream. The majority of women’s prayer did not differ from the daily ritual “conducted at Bais Yaakov schools,” as some of its defenders liked to point out.[8] Still, there was much opposition. It was not an easy matter for Modern Orthodox Jews to simultaneously support women’s Talmud but rebuff attempts to form prayer groups. After all, the Talmud itself (Sotah 20a) discouraged women from opening up its tomes. The sages (Berakhot 22a), on the other hand, permitted women handling a Torah scroll, though later commentators and contemporary critics called that permissive stance into question.[9] Critical sociological and political considerations aside, though, the basic texts of Jewish law provided far more justification for prayer groups than it did for women’s Talmud. Moreover, various women’s prayer groups claimed the support of Rabbi Soloveitchik, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, and Rabbi Shlomo Goren.[10] Of course, this hardly went uncontested.[11] Nonetheless, in the early 1980s there existed more than a dozen well-populated women’s prayer groups, although all but one—Riverdale—met in private homes rather than in the friendlier and more official confines of local synagogues.

The third area of interest for Modern Orthodox women was in the realm of religious leadership. In May 1976, Kehillath Jeshurun on New York’s Upper East Side amended its constitution as follows: “Women who are married to regular members or who are special members are hereby eligible to serve as trustees.” At the congregation’s annual meeting, Rabbi Joseph Lookstein explained that he had met with the Rav and secured his approval.[12] Rabbi Lookstein celebrated the authentically Orthodox decision that kept his congregation at the forefront, or in his terms, as the “pace-setter” of Modern Orthodox Judaism.[13] Others picked up on the “innovation,” but with more than a modicum of caution. For instance, the Young Israel of Plainview elected a woman to its board for the first time in 1980—but one who made it understood that she was uninterested in “dancing with the Torah on Simchat Torah.”[14]

Lookstein was a trailblazer. His granddaughter was one of the first Orthodox bat mitzvah girls in New York, although the practice had been circulating in “out-of-town” communities for decades.[15] There were limits, however, when it came to religious leadership, as opposed to lay leadership. Those who sought the former were not exactly in accord with one another. The first type appealed for gradual and subtle advancement. In 1981, Rabbi Saul Berman told an interviewer that he was not in favor of Orthodox women rabbis but encouraged larger female involvement in halakhic decision making. In fact, Berman had no “doubt in [his] mind that [this would start in] the relatively near future,” especially in “Halacha of particular concern to women, areas such as the Laws of Niddah.” The interviewer pressed Rabbi Berman on whether such a role would require rabbinical ordination. He demurred, explaining that ordination “in and of itself has no legal consequence.” The back and forth continued, but Berman held firm: “I don’t think that Smicha will be a significant issue.”[16]

In contrast, the pioneering Orthodox feminist, Blu Greenberg, was adamant that the title was crucial. “It is to be hoped that the notion of women rabbis ultimately will be accepted in all branches of Judaism,” she argued, “for women can make a valuable contribution to the spiritual growth of the Jewish community.” Without the title, argued Greenberg, “Jewish women with fine minds are being wooed by secular society to make their contributions there, while the door to Jewish scholarship remains, in great part, closed.”[17] Apparently, there was modest support for her position. In 1984, after the Conservative Movement invited women to its leading rabbinical school, Greenberg testified that the “Modern Orthodox community, if not exactly abuzz, is certainly examining the issue from a sober, somber distance.”[18]

Modern Orthodox Judaism was hardly of one mind. Around this time, an assembly of women at Great Neck Synagogue were reportedly “not very receptive” to Blu Greenberg and her somewhat toned down calls for religious change.[19] Yet, the general groundswell of momentum was all too evident. The question I seek to answer is how did these so-called women’s issues fall so rapidly from the Modern Orthodox agenda?

Inauspicious Timing

Surely, part of the answer has much to do with inauspicious timing. First, advocacy of various women’s matters coincided with the struggle at the Jewish Theological Seminary over whether to ordain women. In October 1983, the JTS faculty voted 34-8 to allow women into its rabbinical program.[20] Critics of Orthodox women’s initiatives observed too many parallels to ignore. Detractors of women’s prayer groups alleged that the Orthodox women took their cues from Conservative Judaism.[21] Interestingly, they were not the only ones who detected some comparisons. One prominent Conservative rabbi linked women’s ordination with Stern College’s recently established Talmud program. “Noteworthy and admirable,” affirmed Rabbi Harold Schulweis, “is the decision of the Orthodox Stern College for Women in New York to introduce intensive courses in Talmudic studies for women, a course of studies introduced by none other than Rabbi J.B. Soloveitchik who offered its introductory Talmudic shiur.”[22]

The languishing state of feminism in this decade was a second factor that impaired these endeavors. The very decade that witnessed Sandra Day O’Connor’s appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court and the nomination of Geraldine Ferraro as the first female vice presidential candidate also saw severe backlash to the kind of feminist rhetoric that was so much in vogue a decade prior. In 1982, the Equal Rights Amendment that guaranteed legal gender parity failed a series of state ratifications. Despite their triumphs in the 1970s, the proponents of the movement were branded “antifamily.” Hugely empowered conservative pundits lashed out against liberal politicians who “do not want to help families meet the increasing costs of raising children.”[23] The bulk of successful women’s activism in this period achieved their victories with understated language, and beyond media detection. Those who elected to employ forceful feminist rhetoric usually struggled against the strong rightist cultural currents.[24]

Third, the 1980s proved a precarious moment for the Modern Orthodox, in particular. In that time, Rabbi Soloveitchik was severely limited. Students recalled the “heartbreak” of watching their mentor “struggle to board an airplane, enter and leave a car” and require the support of “two students to help him walk across Amsterdam Avenue,” to his lecture room on Yeshiva University’s campus.[25] During these years, various factions within Modern Orthodox Judaism sometimes put forward competing views, each claiming the Rav’s support.[26] He was in no position to rebut or clarify. In 1985, the Rav retired from Yeshiva and the public scene.

The absence of the Rav’s stabilizing persona within the Modern Orthodox orbit had much to do with a communal crisis of self-confidence. As one rabbinic leader put it: “The question will be, ‘What did the Rav say and when did he say it.’”[27] In the mid-1980s, an outgoing RCA president expressed distress that his colleagues “collapse into miserable surrender” against the outcries of “so-called right-wing Orthodox groups.”[28] No doubt, the Rav would not have supported every initiative. But he also worried about many of his students who, he believed, considered their teacher’s philosophies “persona non grata. My ideas are too radical for them. If they could find another one, it would be alright.”[29] His absence weakened the Modern Orthodox woman’s foothold, even on a few matters that the Rav had once so prominently and undeniably championed.

Bottom-Up Opposition

Modern Orthodox women and their supporters were prepared for all this. Like successful women’s efforts in this time, they were subtle and careful about rhetoric. A minority, of course, were quick to admit that feminism had led to their decisions to form or join a women’s prayer group.[30] Mostly, however, Rivkah Haut and others eschewed any kind of “feminist”—the “F-word”—designation. They feared its politicized implications and the potential alienation from their friends and local Orthodox institutions.[31] To the accusations of Conservative influences, Haut would often shrug and explain that “I can’t help what it looks like. If we wanted that we could go to Conservative shuls.”[32] This language was crucial. Haut hoped to obtain approval from Modern Orthodoxy’s flagship institutions. That did not happen, but their efforts were enough to ensure that the RCA defeated a motion to accept as binding a resolution—undergirded by a much-discussed responsum authored by five leading YU rabbinic scholars—to ban women’s prayer groups.[33]

In large measure, Modern Orthodox women—believing that they were carrying forth the agenda set in the previous decade—knew exactly how to answer some of their most vocal critics.[34] Owing to this, one such opponent warned his rabbinic colleagues that “anybody who dares scorn the fury of the ladies is tempting a fate at least worse than hell.”[35] These grassroots leaders, however, were hardly prepared for the bottom-up opposition. In March 1977, the RCA’s executive vice president told a reporter that the “Orthodox woman by and large is very satisfied with her role within the Jewish community.”[36] For sure, this was something of an overstatement. Other voices, particularly those in better touch with a younger generation of Orthodox women, disagreed. One Manhattan woman described feminism’s impact upon her Orthodox cohort, particularly in light of the “Jewish family.” She acknowledged a “concentration of professional Jewish women in the upper 20s are single, and a lot of religious men can’t deal with it.”[37]

Nevertheless, the Modern Orthodox women’s agenda encountered debilitating false starts, mostly to do with female ambivalence and dissent. First, consider the women’s Talmud initiative. In the wake of the Rav’s path breaking lecture at Stern College, a number of day schools considered taking up the cause. Coed schools in Boston, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Riverdale had a long history of girls Talmud, although for young ladies enrolled at the Yeshivah of Flatbush in the 1970s, Talmud was only available to honors-level female students.[38] For the rest, “while the boys are having a double period of Talmud, the girls are given one period of Halacha and one period of dance.”[39] Subsequently and much to do with the Rav’s influence, Yeshiva University’s Queens-based girls high school added a mandatory requirement in Mishnah and reinforced its Talmud elective.[40] The Frisch School in New Jersey incorporated it into its curriculum, and even invited the Rav to teach and observe. Importantly, in 1979 Rabbi David Silber founded the Drisha Institute for adult female learners on the grounds that it was “preposterous that women who are advancing in all other fields should be held back when it comes to Jewish studies.”[41]

For the most part, though, that was it. Shulamith in Brooklyn instituted an elective course for seniors, but mollified its constituencies by calling it a “Torah She-Ba’al Peh” class rather than Talmud. In 1981, Chicago’s Ida Crown Jewish Academy started a girls Talmud track but it received little traction among female students.[42] Communities in Detroit, Long Island, and St. Louis debated the matter but ultimately decided against teaching Talmud to girls. The subject was not much broached in potential locales like Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Seattle. Lack of consistency motivated one prominent educator to call for Rabbi Soloveitchik and other leaders to come up with a set of official guidelines to retain some of the dwindling momentum.[43]

Interest also waned at Stern College. Two years after the Rav’s lecture, Stern undergraduates still showed far greater interest in “concentrating their learning in Tanach and other areas.” The Beit Midrash Program was “eventually dissolved.” Students complained that they lacked the “learning skills in Talmudic material and the teaching of those skills is not systematically addressed in these content-important classes.”[44] The program reopened a few years later, with modest results. In 1984, a YU student newspaper reported that “only six women joined the Stern Beit Midrash under the tutelage of Rabbi Moshe Kahn.”[45] In all likelihood, the temporary stagnation—it would make a major comeback with the help of Israeli seminaries—provided the necessary courage for one New York rabbi to call into question, before a large audience at a Long Island synagogue, the entire women’s Talmud enterprise, reminding his listeners that Rabbi Soloveitchik’s was very much the minority opinion.[46]

Women’s prayer groups were similarly derailed by apathy, but also with a strong dose of rancor. Here are some excerpts from a maelstrom that took place in the pages of Teaneck’s Jewish press. Unsurprisingly, the local prayer group’s fiercest opponents were women. One demanded to know whether the “members of the Women’s Tefillah [have] consulted directly with today’s Gedoley Hador, such as Rav Moshe Feinstein or Rav Joseph B. Soloveitchik?”[47] Another felt challenged by the accusation that Orthodox women oftentimes feel like “passive observers” in synagogue. Therefore, the critic defensively shot back:

I do not feel inferior because I sit on the women’s side of the Mechitza. And when the wind-chill factor is -2° or it is raining hard outside and my husband and sons have to walk to the synagogue because it is the Sabbath, I am very happy that I can fulfill my religious obligations at home. When the aroma of the “chulent” that I prepare fills my home and my family gathers around the Sabbath table which my daughter set and we eat the challah which my children and I baked, and my family sings “Eishet Chayil”—then I am truly fulfilled as a Jewish wife and mother. And don’t let anyone put that job down—it is a foundation stone without which Judaism cannot survive.[48]

Criticism came in other forms, as well. Prayer groups were far less than satisfying to more progressive change-seekers. In the late 1970s, Blu Greenberg made it clear that she, too, could not align with the prayer group leaders:

I imagine that something is happening in heaven. God on the Kingly throne hears Jews all over the world calling his name. And then he says, “Why do women deny my kingship?” It’s not a simple question of what does God want. But it’s strange that these women can’t say certain things, it’s strange that there is an active leaving out of women from the spiritual congregation.[49]

Most of all, Greenberg objected to the separatist character of these groups. To her, it made far more sense to educate and identify opportunities for women within the general context of the service—with women and men participating. In her 1981 book, she described women’s prayer as an “interim solution at best.” And, she prophesied quite correctly that a “separate minyan will continue to be satisfying only for a small number of women.”[50]

Conclusion: A History of Discontinuities

The 1990s proved far more welcoming to a new wave of self-identifying Orthodox feminists. Yet, it was a very different sort of effort. In the decade earlier, Blu Greenberg’s attempt to lobby for Orthodox women’s ordination had not moved all too much. In 1993, she confessed that the “lines have hardened.” More grievous still, from her vantage point, “Orthodox women themselves are largely inhospitable to the idea.”[51] Of course, if Modern Orthodox women were not all that keen on prayer groups and Talmud, then there was little chance that they would support the more egalitarian-minded rabbinate campaign.

This did not stop Greenberg. To the contrary, she continued to lead her Orthodox feminist cause. In 1997, she founded the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance. She established this with grand fanfare. JOFA was unabashedly feminist and avowedly antiestablishment. It was something unprecedented in Orthodox Jewish life. Along with Edah, it was the first of a host of institutions that sought to influence the mainstream from the outside.

This, then, is a history of discontinuities. The new Orthodox feminist agenda emerged from the unfulfilled aspirations of the 1980s. The current model lacks the “insiderness” of its predecessors—but it is perhaps better prepared for the invariable ups and downs. Of course, it is not for historians to determine the worthiness of any of these endeavors. It is their responsibility, however, to sort through all of the continuities and discontinuities, and to figure out how we arrived at this curious and complex moment.

[1] “Polarization within Orthodoxy Must be solved by Dialogue Not Battle,” Jewish Press (June 15, 1984): 24. Note: this paper was originally delivered on Sunday, January 15, 2017, at the JOFA Conference 2017.

[2] Margy-Ruth Davis, “Modern Orthodoxy,” Tradition 20 (Winter 1982): 368. For the symposium, see “The State of Orthodoxy,” Tradition 20 (Spring 1982): 3-83.

[3] See, for example, Gitelle Rapoport, Letter to the Editor, Tradition 20 (Winter 1982): 368; and Joel B. Wolowelsky, “Modern Orthodoxy and Women’s Changing Self-Perception,” Tradition 22 (Spring 1986): 65-81.

[4] S. Joseph, “A Check List: How Good is Your School?” Jewish Observer 2 (January 1965): 12. I thank Shimon Steinmetz for alerting me to this source.

[5] See Zev Eleff, Modern Orthodox Judaism: A Documentary History (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2016), 209-10.

[6] Joel B. Wolowelsky, “Modern Orthodoxy and Women’s Changing Self-Perception,” 78.

[7] See Areyh A. Frimer and Dov I. Frimer, “Women’s Prayer Services—Theory and Practice,” Tradition 32 (Winter 1998): 5-118.

[8] See Irwin H. Haut, “The Halacha On Women Minyon,” Jewish Press (September 21, 1984): 42.

[9] See Avraham Weiss, “Women and Sifrei Torah,” Tradition 20 (Summer 1982): 106-18.

[10] See, for example, Toby Fishbein Feifman, “Members Clarify Women’s Tefillah,” Jewish Standard (February 24, 1984): 12. See also, Shlomo Riskin, Listening to God: Inspirational Stories for my Grandchildren (New Milford: Maggid, 2010), 193-96.

[11] See Moshe Meiselman, Jewish Women in Jewish Law (New York: Ktav, 1978), 197 n.64; Louis Bernstein, “Rabbi Bernstein Replies On Women’s Minyon,” Jewish Press (November 23, 1984): 5; and “Teshuvah bi-Inyan Nashim bi-Hakefot.” Ha-Darom 54 (Sivan 1985): 51–53.

[12] See Bernard Postal, “Postal Card,” Jewish Week (October 9, 1976): 25.

[13] “Congregation Votes in Favor of Women Trustees,” Kehilath Jeshurun Bulletin 43 (May 14, 1976): 1.

[14] See Marta Beri Shapiro, “Women in Synagogues on Long Island,” Jewish World (April 4, 1980): 17.

[15] See Zev Eleff and Menachem Butler, “How Bat Mitzvah Became Orthodox,” Symposium on Mesorah (Torah Musings: 2016), 20.

[16] Saul Berman and Shulamith Magnes, “Orthodoxy Responds to Feminist Ferment,” Response 12 (Spring 1981): 16-17.

[17] Blu Greenberg, On Women and Judaism: A View from Tradition (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1981), 10.

[18] Blu Greenberg, “Will There Be Orthodox Women Rabbis?” Judaism 33 (January 1984): 23.

[19] See Stewart Ain, “Religious Role of Orthodox Women is Changing,” Jewish World (February 11, 1983): 17.

[20] Pamela S. Nadell, Women Who Would Be Rabbis: A History of Women’s Ordination, 1889-1985 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998), 212.

[21] Dvorah Shurin, “On a Minyan for Women,” Jewish Press (December 24, 1982): 5.

[22] Harold M. Schulweis, “Rabbi Wanted: No Women Need Apply,” Reform Judaism 12 (Fall 1983): 10.

[23] George Gilder, “An Open Letter to Orrin Hatch,” National Review 40 (May 13, 1988): 34.

[24] See Sara M. Evans, “Feminism in the 1980s: Surviving the Backlash,” in Living in the Eighties, eds. Gil Troy and Vincent J. Cannato (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 85-97.

[25] See Howard Jachter, “The Rav as an Aging Giant (1983-1985),” in Mentor of Generations: Reflections on Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, ed. Zev Eleff (Jersey City: Ktav, 2008), 330.

[26] See Larry Cohler, “RCA Suspends Orthodox Pre-Nuptial Agreement,” Jewish World (November 23, 1984): 12-14.

[27] Larry Yudelson, “After the Rav: RCA Rabbis Listening for Master’s Voice,” Jewish World (May 29, 1987): 20.

[28] See Stewart Ain, “Rabbinical Council President Decries Holier-than-Thou Attitude of Right Wing,” Jewish World (March 1, 1984): 14.

[29] See Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, vol. II (Hoboken: Ktav, 1999), 240. I thank Lawrence Grossman for pointing out this source to me.

[30] See “Davening with Women,” Jewish World (November 9, 1979): 7.

[31] See Sylvia Barack Fishman, A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community (Hanover: Brandeis University Press, 1993), 158-68.

[32] See Larry Cohler, “Women’s Davening Group Comes into its Own, Despite Criticism,” Jewish World (July 13, 1984): 18.

[33] See Rabbinical Council of America Executive Committee Minutes, February 27, 1985, Box 6, Rabbi Louis Bernstein Papers, Yeshiva University, New York, NY.

[34] On these criticisms and analyses, see Adam Ferziger, “Feminism and Heresy: The Construction of a Jewish Metanarrative,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 77 (September 2009): 494-546; and Rachel Adler, “Innovation and Authority: A Feminist Reading of the ‘Women’s Minyan’ Responsum,” in Gender Issues in Jewish Law: Essays and Responsa, eds. Walter Jacob and Moshe Zemer (New York: Berghahn Books, 2001), 3-32.

[35] Louis Bernstein to RCA Colleagues, December 23, 1984, Box 14, Folder 8, Rabbi [Irving] Greenberg Papers, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

[36] See Irving Spiegel, “Judaism is Called Cool to Feminism,” New York Times (March 6, 1977): 54.

[37] See Zev Brenner, “The Roving Jewish Eye,” Jewish Press (November 26, 1982): 4.

[38] See Seth Farber, An American Orthodox Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Boston’s Maimonides School (Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2004), 68-87; and Jeffrey S. Gurock, “The Ramaz Version of American Orthodoxy,” in Ramaz: School, Community, Scholarship, and Orthodoxy, ed. Jeffrey S. Gurock (Hoboken: Ktav, 1989), 59.

[39] See Eleanor Finkelstein, “A Study of Female Role Definitions in a Yeshivah High School (A Jewish Day School)” (PhD diss., New York University, 1980), 78-79. I thank Seth Farber for identifying this source.

[40] See Arthur M. Silver, “May Women Be Taught Bible, Mishnah and Talmud?” Tradition 17 (Summer 1978): 80-81.

[41] Soshea Leibler, “Teaching Talmud to Women,” Baltimore Jewish Times (May 30, 1980): 11.

[42] In fact, the augmented curriculum was not even mentioned in the yearbook, among other recent innovations. See “Memories,” ICJA Keter (1981): 58.

[43] See Alvin I. Schiff, “The Centrist Torah Educator Faces Critical Ideological and Communal Challenges,” Tradition 19 (Winter 1981): 282-83.

[44] Shoshana Jedwab, “Talmud Torah at Stern College,” Hamevaser (September 1985): 5.

[45] Aviva Ganchrow, “On the Other Side of the Mechitza,” Hamevaser (November 1984): 6.

[46] See Melanie B. Shimoff, “Speakers Debate Orthodox Women’s Role,” Jewish World (March 18, 1983): 13.

[47] Judith Rosenbaum, “Oppose Women’s Tefillah,” Jewish Standard (February 10, 1984): 3.

[48] Anne Senter, “Oppose Women’s Tefillah,” Jewish Standard (February 10, 1984): 13.

[49] “Blu Greenberg: Distinct and Equal,” Jewish World (November 9, 1979): 7.

[50] Blu Greenberg, On Women and Judaism: A View from Tradition (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1981), 95-96.

[51] Blu Greenberg, “Is Now the Time for Orthodox Women Rabbis?” Moment 18 (December 1993): 51.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.