Moshe Kurtz

Do national flags belong in our synagogues?[1] The Jewish people are familiar with the concept of a flag, whether it be the biblical tribes living in the wilderness (Numbers 2:2) or seventeenth-century Jews attending the Old New Synagogue (Altneuschul) in Prague. However, controversy over the place of flags in synagogues first emerged in the twentieth century.

What makes the modern issue of flags pertinent is twofold: first, it will serve as a case study for understanding how recent rabbinic thinkers reckoned with the principles of Zionism, American patriotism, and nationalism writ large. Secondly, the question of placing national flags specifically within the synagogue’s sanctuary will require us to deepen our understanding of the imperative to uphold kedushat beit ha-kneset, the sanctity of the synagogue.

We will initially survey noteworthy rabbinic authorities who either supported, rejected, or merely tolerated national flags. Subsequently, we will analyze whether placing such flags in the synagogue’s sanctuary presents a further challenge or a unique opportunity.

I . Reasons to Promote National Flags

Dr. Yeshayahu Leibowitz once quipped that the Israeli flag is nothing more than a “rag hanging on a pole.”[2] However, for many, it represents much more than a reductive physical description. Students of R. Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, such as R. Aharon Ziegler, record the following:

Regarding the Halachic significance of the Israeli flag, Rav Soloveitchik said that he did not think that flags and ceremonies have any significance.[3] However, [Rav Soloveitchik said,] let us not ignore a basic law in Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh Dei’a, Hilchot Aveilut, that if a Jew is killed by Gentiles he is buried in his clothing, so that his blood will be visible, and people will avenge it. The clothes of a Jew become holy to some degree when they are stained with holy blood, and this is certainly true of the blue and white flag, which is soaked in the blood of thousands of young Jews who fell in the defense of the land and the settlements. It has a spark of Kedusha which stems from dedication and self-sacrifice. We are all obligated to honor the flag of Israel and to show respect for it.[4]

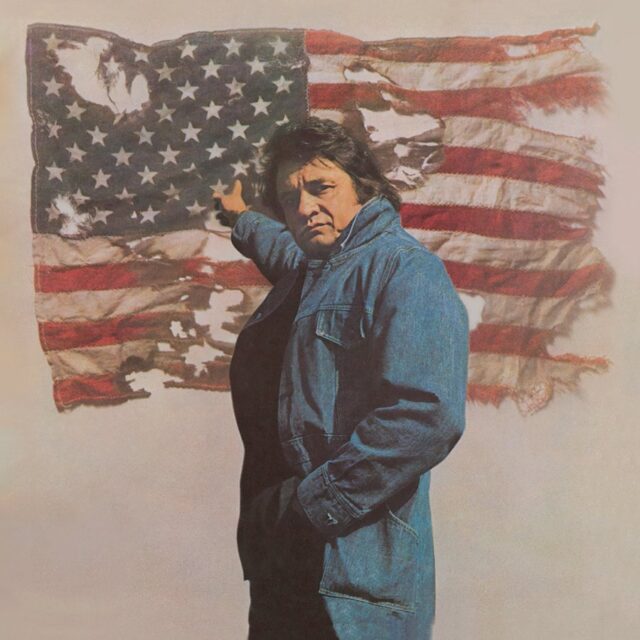

R. Soloveitchik draws an analogy from Rema’s (Yoreh De’ah 364:4)[5] reverence for a single martyr’s blood-soaked clothing to the symbolism of the Israeli flag which represents the blood of thousands of martyrs.[6] R. Soloveitchik’s rationale need not be limited to the Israeli flag but can be used to understand the imperative for honoring the American flag as well. In “Ragged Old Flag,” Johnny Cash expresses a similar sentiment vis-a-vis the United States: the flag is much more than just a ragged piece of fabric—it is a symbol of all who bled and sacrificed to protect the people of their country. Indeed, the service flag hung in many synagogues during World War I began as a demonstration for honoring their members serving in the armed forces, and it likely set a precedent for normalizing national flags in the sanctuary.

Shortly after the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Texas v. Johnson (1989) that flag burning constitutes symbolic speech protected by the First Amendment, R. Avigdor Miller was asked to opine on the matter. In a transcription of his oral response, R. Miller asserted that it is our duty to honor the American flag:

And therefore we have to be very displeased with those people who go as low as to burn the American flag. The flag is a symbol of all the privileges that Hakodosh Boruch Hu is giving us in this country. And therefore it’s not a bad idea – even if you never did it before – to hang out a flag on the Fourth of July, l’hachis ha’rishaim [to spite the wicked]. It’s not a goyishe thing. No! Do it l’hachis – to show them that, yes, we do appreciate what Hashem gave us.[7]

R. Miller not only supported the American flag but also advocated for flying it on the synagogue premises in honor of July 4th, American Independence Day.[8] In addition to R. Soloveitchik’s rationale that a national flag represents those who fell in its defense, R. Miller emphasized the importance of demonstrating gratitude for the privileges that its country grants us.

Whether one views a national flag as a symbol of self-sacrifice or as a reminder to demonstrate hakarat ha-tov (gratitude), both rationales can be applied to the United States and Israel. However, what makes the Israeli flag especially unique is that it represents a Jewish state. Whereas the United States deserves to be recognized as a benevolent country, it could be argued that it is fundamentally different from the State of Israel which might play a role in bringing about the destiny of the Jewish people on God’s holy land. R. Moshe Malkah writes:

In my opinion there is no issue with placing an Israeli or American flag in the sanctuary. On the contrary, it is honorable and glorious for the State of Israel’s flag to hang over the holy ark in order to demonstrate to those gathered that the Torah of Israel and the Land of Israel are one and the same. For the flag of Israel necessitates being bound to the Torah of Israel.[9]

While R. Malkah merely permits the American flag, he enthusiastically advocates for the flying of the Israeli one as it uniquely serves as a call to bring about the destiny of a Jewish people in the Holy Land living according to the dictates of the Torah.

While some might be uneasy with the innovation of the Israeli flag, R. Dr. Ari Shevat asserts that such a flag should not be an unfamiliar concept to the Jewish people:

If the Holy One Blessed be He celebrated the distinct identity of every tribe through their respective flags, certainly (kal va’-homer) God celebrates when a flag serves to distinguish the identity of the entire Jewish people from the rest of the nations, [as the Midrash[10] states:] Said the Holy One Blessed be He, the nations of the world have flags, however the only flag that is beloved to me is the flag of Jacob.”[11]

For Religious Zionists,[12] the flag of Israel is not simply a national flag, but it is a fulfillment of our liturgy in which we beseech God to “raise a banner to gather our exiles, and gather us together from the four corners of the earth.” However, as we will see momentarily, not everyone viewed the State of Israel through the same rose-colored glasses.

II. Principled Opposition to National Flags

While our guiding question is whether one should display a flag in synagogue, R. Menashe Klein addresses this issue from a notably different point of departure: “Is it permissible to pray in a synagogue that has a Zionist flag which signifies the State of Israel?” Hardliners like R. Klein presuppose that it is obviously problematic to place an Israeli flag in a synagogue; thus, the scope of their inquiry is whether one who finds themselves in a synagogue bearing an Israeli flag may pray there.

Initially, R. Klein cites the suggestion of a R. Mordechai Savitsky who contended that the Israeli flag represents a form of avodah zarah (idolatry); however, he ultimately concludes:

However, [R. Savitsky] fundamentally erred in his analogy. Certainly this flag does not have any element of idolatry, for these Zionists [who founded the State of Israel] were not idolaters – on the contrary they were absolute deniers (kofrim ba-kol)! In the multitude of our sins, they [essentially] stated “My own power and the might of my own hand [have won this wealth for me]” (Deut. 8:17). And they [further] say, God forbid, that “there is no judgment and no Judge” [Vayikra Rabbah 28:1]. Accordingly, this flag that they established is not [related to] idol worship, rather it is a symbol for their rejection [of God] and their wickedness – woe to them and woe to their souls![13]

While those sympathetic to the Israeli flag might appreciate that R. Klein disagreed with those who diagnosed it as idolatry, they might be dismayed to learn that he only disagreed because he thought it fell under the category of heresy instead.

However, it behooves us to ask why the State of Israel, a country dedicated to the protection and welfare of the Jewish people, met such a negative reception among many of the most preeminent rabbinic scholars. When the question of displaying an Israeli flag in the synagogue was raised in a previous issue of the journal Koveitz Ha-maor, R. Dr. Solomon Michael Neches, a prominent rabbi from California, wrote back: “Can the inquirer please explain why his question singled out “the blue-and-white flag.” After all, the American flag is standing there right next to the blue-and-white flag. So why did he not address his “question” in regards to both flags?”[14]

Indeed we can observe many instances in which the American flag not only escaped rabbinic censor, but was used to kasher the presence of the Israeli flag. R. Hershel Schachter records in Nefesh HaRav (pp. 99-100) that there was once an Agudas Yisroel convention held at a hotel in Jerusalem in which the organizers were uncomfortable with the presence of the Israeli flag. Seeing as removing the Israeli flag would not be viable, they instead opted to hang the flags representing the nationalities of all the convention’s participants. Thus the flags of countries such as America, France, and Britain in essence kashered the existence of the Israeli flag. Both R. Klein and R. Moshe Feinstein made a similar suggestion for tolerating the presence of the Israeli flag inside the synagogue. R. Feinstein writes:

Even though those who made this flag and symbol of the State of Israel were wicked, nonetheless, they never established it as a sacred entity, to the degree that we would need to be concerned that it would lead to idolatry. For it is known to all that this was merely a general symbol and is a secular entity. The fact that the American flag is also there proves that they did not bring in [the Israeli flag] because they regard it as a holy entity, rather it is [just] a symbol that the synagogue administration has affection (she-mihavevin) for this country and for the State of Israel – and they just want to display it in a place where they will be seen…[thus] it is not plausible to claim that this constitutes idolatry, rather it is [simply] vanity and silliness (hevel u-shtus).[15]

While R. Feinstein would prefer the absence of the Israeli flag, he appears to be more tolerant than some of his Haredi compatriots. So long as the Israeli flag is regarded as no different than any other national symbol, its presence can be abided. However, should the Israeli flag assume a religious status, it would seem that even R. Feinstein would be forced to put his foot down.

R. Feinstein would appear to take less issue with a secular-Zionist orientation toward the Israeli flag than the religious-Zionist community, in which many regard it with a sacred stature. Many of the Haredi opponents of the Israeli flag tend to focus on the secular aspects of Zionism. Take for instance R. Miller’s sentiments toward the Israeli flag:

The Israeli flag is a symbol of Zionism…Zionism is not just some political movement; it represents the principle that in order to be a Jew all you need is to subscribe to the idea of a Jewish state. You don’t need any Torah. You know you can be an atheist and you can still be a very good Zionist! And that’s where we come in and we say, that’s the chillul Hashem! … And therefore a flag that proclaims that the Torah is not necessary to be a Jew – that you can be an oichel treifos (eat non-kosher)…you can be a michaleil Shabbos (desecrator of Shabbos), and work on Yom Kippur, and be an eishes-ishnik, you can commit adultery, it’s nothing to them.[16]

Thus, the primary opposition to the Israeli flag is not necessarily due to a lack of recognition for what the country provides nor from an antagonism toward the Land of Israel, which is clearly sacred. Rather, the primary Haredi aversion stems from a profound dissatisfaction with the State of Israel in its current iteration versus what they believe it ought to be.[17]

Indeed, national flags can serve as a form of a Rorschach test: two people can see the same piece of fabric and walk away with diametrically opposed interpretations about what it represents. Some will be moved to gratitude for all the positives that the country has done, while others will feel a sense of disappointment for what it currently fails to provide.

III. The Sanctity of the Synagogue

Let us now grant the premise that there exist no fundamental objections to both the Israeli and American flags. The second piece of this equation is determining whether the synagogue, particularly its sanctuary, serves as the appropriate place to display these symbols. While some authorities expressed a relative tolerance for national flags, situating them next to the holy ark incurred the ire of many prominent rabbis.

(1) Distractions During Services

R. Aharon Simcha Blumenthal[18] invokes the concern of Shulhan Arukh regarding visual distractions during prayer: “[Regarding] illustrated garments, even though [the image] does not protrude (ie. like an embroidered garment), it is not proper to pray in front of them. And if one happens to pray (i.e. he has no choice) in front of an illustrated garment or wall, he should close his eyes” (Orah Hayyim 90:23).

Shulhan Arukh is generally concerned with anything that presents a distraction during prayers, and R. Blumenthal believes that flags would qualify as such. However, one needs to take a genuine look at our synagogues and ask if the national flags are truly more distracting than some of the other ornaments that receive far less scrutiny.

(2) The Analogue of the Muslim Prayer Mat

One of the most common precedents cited in opposition to placing national flags in synagogue was the Responsa of the Rosh (Klal 5, Siman 2), which forbade hanging of a mat with the image of a scale in the synagogue since such a mat was commonly used by Muslims for their prayers. He writes that “it appears to me that it is forbidden to hang this in the synagogue – certainly next to the side of the sanctuary.” However, if we grant the premise that there is nothing fundamentally idolatrous about national flags, then it would make our case less analogous to the case of the Rosh.

(3) The House of God is Only for God

While we may grant that national flags do not carry the problematic associations of another religion, displaying them in the sanctuary, especially next to the ark, risks conveying an erroneous message.

R. Avraham Chaim Naeh cites Berakhot 49a, which explains that God’s kingship is not invoked in the third blessing of Birkat Ha-Mazon because it would be inappropriate (lav orah ar’a) to mention it alongside the kingship of David, as it would appear to equate God’s dominion with that of a mortal. Likewise, R. Naeh asserts, it would be inappropriate to display national flags next to the holy ark, since it places God and government on the same playing field.[19]

From a slightly different standpoint, R. Meir Amsel cites the following ruling codified by Rema (Orah Hayyim 98:1): “And it is forbidden for a person to kiss one’s small children in synagogue, in order to fix in one’s heart that there is no love like the love of the Omnipresent Who is Blessed.”[20]

Certainly it is not an affront to God for a parent to love their own child. Rather, the location where parents choose to express their affection may be inappropriate. Jewish law sets laws that govern the kedushat beit ha-kneset, the sanctity of the synagogue. While eating and drinking are necessary human functions, they may not be done within a synagogue’s sanctuary.[21] Similarly, Judaism expects that a parent should bear affection for their child, but it is simply not appropriate to display that in the beit ha-kneset, a place designated exclusively for demonstrating affection and allegiance to God. Likewise, while expressing appreciation for one’s country may be commendable, the beit ha-kneset is perhaps not the appropriate place to demonstrate it.[22]

(4) Christians and the Alleged Worship of America

While most of the aforementioned arguments have been made vis-a-vis the Israeli flag, R. Hillel Posek argues that the American flag constitutes an even bigger issue:

It is repugnant in a location in which [we express] that “we are for God and our eyes are to God,” to [demonstrate] a reliance on the guarantees of the American flag. For the Torah has already stated, “Yet even among those nations you shall find no peace” (Deut. 28:65). For we should only rely upon our Father in Heaven, and not which the masses think to pray to the flags and the military might which they represent.[23]

Granted, most people are likely not directing their prayers to the American (or Israeli flags); however, the optics convey a certain set of values that some rabbinic authorities find questionable.

Rabbis who subscribe to R. Posek’s opposition to placing the American flag in the sanctuary are not alone. R. Meir Amsel, in disagreeing with the more tolerant position of R. Feinstein cited above, employs the following argument:

Regarding the Zionist flag in synagogues. It is known to all that the intention behind their placement is to acculturate those praying there with a love of Zionism in place of a love of the Creator. Go out and see the desecration of God’s name in this matter, for even the nations of the world will not bring flags into their houses of worship – only we who have become lower than any other nation.[24]

R. Amsel is seemingly referring to an ever-growing frustration among Christian theologians with the near deification of the American flag. Dr. Jonathan Sarna explains how the American flag developed religious-like qualities in the late 19th century. “The aftermath of the divisive Civil War, followed by the immigration of millions of foreigners to America’s shores, generated — even more than in Europe — a civil religious devotion to the national flag as an emblem of national unity. America soon pioneered the world in developing flag-related holidays and rituals, such as Flag Day…and the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag.”[25]

Concern with conflating American patriotism and worship of God has led to strong pushback from certain segments of the Christian community. In the publishing of a 2005 issue of Pepperdine University’s Christian journal Leaven, Craig M. Watts writes:

A natural love for one’s own country coupled with a dedication for the wellbeing of all is a form of patriotism compatible with discipleship. There are ways that Christians as individuals can appropriately display patriotism. But the same cannot be said for a church. Because of the nature of the church’s identity and mission, patriotic expressions have no legitimate place in its worship and ministry… The so-called patriotic hymns are most often songs of praise to a personification of the country and not a means of truly glorifying God. “My country, ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing,” or “America, America, God shed his grace on thee.’” The “thee” is not God but country. If these are songs of worship, it is false worship. God is mentioned as a supporting figure, a means to bolster the greatness of the nation, which is the real object of adoration in the hymns. We should label this for what it is—idolatry.[26]

Taking a similar stance, another contributor to the same issue of Leaven, Dr. Micki Pulleyking, shares her church’s conclusion when they explored the question of patriotic displays in church:

Why would you ever say the Pledge of Allegiance in a sanctuary where the church gathers weekly to proclaim their loyalty to God alone? Our study led us to three important conclusions: First, whenever a national symbol is displayed in the church it is an unspoken form of idolatry. Second, Christians are to remember that their true citizenship is not tied to any country but to the kingdom of God. Third, the God Christians claim to worship is the God of all persons, the creator God who equally loves all creation.[27]

While the full extent of Christian opinions on this matter falls beyond the scope of this essay, it is noteworthy to see that some Christian thinkers have employed very similar lines of argumentation to the rabbinic sources who also emphasized that our sole allegiance is to God.[28] Patriotic displays in synagogues present a similar challenge. For even when we invoke God’s name in prayers for the state, it is imperative that He not become relegated in our eyes to a “supporting figure,” to borrow Watts’ formulation.[29]

An important takeaway from the Christian opposition to displaying national flags in church is that it demonstrates that this conversation is not necessarily contingent on how one relates to Zionism and the Jewish state. These theologians are not concerned with the Jewish debate surrounding Zionism, yet they still reached similar conclusions to many of the rabbinic authorities we have reviewed. In other words, one can maintain a strong appreciation for their country while still believing that the sanctuary is not the most appropriate place for such demonstrations.

IV. Conclusion

From a halakhic standpoint, it would be difficult to make a cogent argument to remove national flags from a synagogue – and certainly, to contend that one may not pray at such a place. R. Klein among many others notes that the Old-New Synagogue in Prague proudly displayed a flag and that the numerous Torah scholars who prayed there were not known to have protested its existence. Furthermore, R. Klein cites a Talmudic story (Avodah Zarah 43b),[30] in which a number of prominent sages did not refrain from praying in a synagogue that displayed a statue of the king. While the presence of the statue was clearly not desirable, it did not invalidate the status of the synagogue as a legitimate place of prayer. R. Feinstein makes the same point by citing Magen Avraham, who ruled that if someone committed a sexual sin inside a synagogue, it did not detract from its status as a beit ha-kneset—certainly a national flag should be no worse.[31]

It would seem that the propriety of displaying flags in synagogue need to be determined instead on meta-halakhic grounds. On the one hand, national flags serve as a reminder to those who sacrificed their lives for us, and the Israeli flag in particular may be a symbol of God returning the Jewish people to their homeland as “the beginning of the flowering of our redemption.” According to R. Malkah there is an added imperative to inculcate into our hearts that the “Torah of Israel and the Land of Israel are one and the same.” On the other hand, some have raised fundamental issues with national flags, particularly the Israeli one, which represents to them a government which deliberately neglects to rule God’s land according to His Torah. Leaders like R. Miller and his school of thought would brand the flag as representing idolatry or kefirah.

The middle ground between these two poles is occupied by those who view national flags as legitimate, but strongly question whether the synagogue and its sanctuary are the appropriate venue to display them. While the Israeli or American flag may not be inherently idolatrous in nature, placing them next to the holy ark might come uncomfortably close to conveying such a message. Appreciation for Israel and America should be encouraged, but like loving one’s own child, the sanctuary may not be the right place to express such affection – for it is solely the house of God.

With these considerations in mind, let us conclude with a passage from the end of R. Feinstein’s responsum on the matter: “If it is possible to remove the flags from the synagogue in a peaceful manner, it would be a good thing – but it would be forbidden to [do so if it would] cause discord.” R. Feinstein believed that shalom, peace, in the congregation takes priority in this scenario.[32] While the question of whether to display a flag in the synagogue and its sanctuary is important, there are other factors that need to be taken into the equation. In a similar fashion, R. Klein suggests that our paramount concern should be “with whom we pray, for prayer is supplication, and God desires what is in our hearts.”[33]

National flags are complex symbols that represent different ideas to different people. An introspective community should take all of the aforementioned considerations into account. Ultimately, whatever they do conclude, they should make the decision in a manner that upholds the integrity of the community and encourages them to proudly bear the banner of God.

[1] I would like to express my gratitude to Yisroel Ben-Porat for editing this piece, and to R. Yair Lichtman for his invaluable insights.

[2] Oreshet Vol. 1 (5770) Mikhlelet Orot Yisrael (pp. 297-342), n. 14.

[3] This is consistent with R. Soloveitchik’s general opposition to inventing new rituals, as he branded religious innovation absent a Divine mandate as a form of paganism. See, for example, Darosh Darash Yosef (pp. 333-338).

[4] R. Aharon Ziegler, “Halakhic Significance of the Israeli Flag” (Torah Musings 9/2/2016).

[5] Text as follows: “If they found a slain Israelite, they may bury him [in the same condition] as they found him without shrouds, and they do not even remove his shoes. Gloss: Thus they do [with respect] to a woman in confinement who died, or regarding a person who fell down and died. Some say that they wrap them over their garments [with] shrouds. The accepted practice is that one makes no shrouds for them as [for] other dead, but one buries them in their garments over which [they place] a sheet as [in the case] of other dead.”

[6] R. Hershel Schachter communicated to me that he was not aware of whether R. Soloveitchik explicitly opined on the issue of displaying an Israeli flag in the synagogue.

[7] “Rav Avigdor Miller on Flag Burning and Flag Hanging” (Tape #790, July 1990).

[8] “Rav Avigdor Miller on The Fourth of July” (Tape #833, July 1991).

[9] Responsa Mikveh Ha-Mayim (Vol. 5, Orah Hayyim, p. 21).

[10] Midrash Tanhuma (Numbers, no.10) based on Song of Songs (2:4), “He brought me to the banquet room, and his banner of love was over me.”

[11] R. Dr. Ari Yitzchak Shevat, Oreshet Vol. 3 (5772) Mikhlelet Orot Yisrael (pp. 297-342). Many of Shevat’s stand alone articles, such as those cited here, were later synthesized into Le’-harim et Ha-Degel, a remarkably researched work about the Israeli flag and Hebrew language.

[12] For R. Abraham Isaac Kook’s view on the significance of the Israeli flag, see Ha-Maayan, Nisan 5769 (49:3).

[13] Responsa Mishneh Halakhot 19:116. See also Mishneh Halakhot (4:110) where R. Klein addresses a similar issue regarding the permissibility of praying in a synagogue that displays images of animals.

[14] Koveitz Ha-maor, Vol. 2, no. 12 (18) Heshvan 5712 (p. 15). See further citations from this journal collected in Petihat Ha-Igrot (pp. 50-51).

[15] Responsa Igrot Moshe, Orah Hayyim 1:46.

[16] “Rav Avigdor Miller on Burning the Israeli Flag” (Tape #252, January 1979). It is noteworthy that the same R. Miller, who spoke in such lofty terms about protecting the honor of the American flag, also expressed absolute opposition to the Israeli standard. And similar to R. Feinstein, he only addressed the secular approach to Zionism, while either being unaware of or purposely omitting the existence of many religious Zionists who want nothing more than for Israel to be realized as a halachic theocracy.

[17] The Haredi opposition addressed in this essay reflects the mainstream view which is in principle comfortable with reclaiming the Land of Israel, but is practically disappointed that it is not governed according to Jewish law. It should be noted that the Satmar sect fundamentally opposes returning to Israel at this point in time based on their understanding of Ketubot 111a. Thus, for the Satmar school of thought, the question of relating to any form of an Israeli symbol is moot.

[18] Quoted in Responsa Hillel Omer, no. 37. R. Blumenthal advances the argument in Koveitz Ha-maor, Vol. 2, no. 12 (18) Heshvan 5712 (p. 15).

[19] Koveitz Ha-maor, Av 5712, p. 3. R. Blumenthal cites the following verse as evidence for the same position: “There was nothing inside the Ark but the two tablets of stone which Moses placed there at Horeb, when the LORD made [a covenant] with the Israelites after their departure from the land of Egypt.” (I Kings 8:9). This verse implies that only the two tablets belong in the ark, and no other object, including flags. However, R. Blumenthal would need to reckon with the medieval commentaries (e.g. Malbim and Abarbanel ad loc.) who seek to reconcile this with the Talmudic account that there were indeed other items contained within the Ark. Furthermore, the flags are generally not inside the synagogue’s ark but placed to the side of it.

[20] Koveitz Ha-maor (Vol. 2, no. 12 (18) Heshvan 5712, pp. 15-16). See also Binyamin Ze’ev (responsum 163) and Agudah in chapter six of tractate Berachot.

[21] Mishneh Torah, Prayer and the Priestly Blessing 11:6.

[22] It should be noted that the rules for a beit midrash are generally more relaxed than a room that bears the status of a beit ha-kneset. See Ran (Commentary on Rif 9a, s.v. Ravina), Rema (Orah Hayyim 151:1) and Beiur Ha-Gra (ad loc.).

[23] Responsa Hillel Omer, no. 37, p. 24.

[24] Koveitz Ha-maor, Vol. 14, no. 10 (148) Kislev 5725, p. 23. R. Amsel makes reference to Magen Avraham (Orah Hayyim 244:8), who forbade the use of leniencies to allow gentiles to construct a synagogue on Shabbat since gentiles would never conscience having their houses of worship constructed on their holidays.

[25] Jonathan D. Sarna, “American Jews and the Flag of Israel.” See also idem, “The Cult of Synthesis in American Jewish Culture,” in Coming to Terms with America: Essays on Jewish History, Religion, and Culture (Philadelphia: University of Nebraska Press, The Jewish Publication Society, 2021).

[26] Craig M. Watts, “Theological Problems with Patriotism in Worship,” Leaven 13.4 (2005), Article 4.

[27] Micki Pulleyking, “Flying the Flag in Church: A Tale of Strife and Idolatry,” Leaven 13.4 (2005), Article 3.

[28] R. Dr. Shevat argues that Judaism differs from Christianity as the former contains an explicit national component; Oreshet Vol. 2 (5771) Mikhlelet Orot Yisrael (pp. 153-200). However, the phenomenon of Christian nationalism in America offers a compelling analogy.

[29] While the scope of this essay is limited to national flags, it is worthwhile to consider the reception of national prayers in synagogue. While they are similar issues, it is worth noting that making prayers for one’s own country is a longstanding Jewish practice based on Jeremiah 29:7, as adapted in Avot 3:2. See also Noda Be-Yehudah, 2nd ed., Even Ha-Ezer 88.

[30] See also Rosh Ha-Shanah 24b.

[31] I would like to thank R. Naftali Wolfe for pointing out to me that while the passage in Avodah Zarah serves as a valid precedent, the case of Magen Avraham is less analogous since the sexual sin took place before services whereas the flags are on display during services.

[32] Responsa Igrot Moshe, Orah Hayyim 1:46. See Yalkut Yosef (Orah Hayyim Vol. 6, Laws of Torah Reading, Torah Scrolls and Synagogue, p. 429), which rules in accordance with Igrot Moshe. Also, see Igrot Moshe, Orah Hayyim 3:15, in which R. Feinstein addresses the status of Stars of David in the synagogue. Similar to the case of flags he concludes that an item bearing a Star of David with the word “tziyon” should be removed only in a way that avoids discord. It is noteworthy that R. Feinstein adopted a conciliatory position on this issue, whereas on other modern issues such as the Conservative Movement (Igrot Moshe, Yoreh De’ah 2:100-108) and feminism (Igrot Moshe, Orah Hayyim 4:49) he was far more unyielding.

[33] Responsa Mishneh Halakhot 19:116, citing Berakhot 26a and Zohar, Vol. 2, 162b.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.