Yiscah Smith

Its Beginning

Shortly prior to Moses’ passing, after the forty-year sojourn in the wilderness, the Eternal invites Moses to ascend a nearby mountain to view from afar the Promised Land that the Children of Israel will soon inhabit. After forty years of leading his flock to the Promised Land, Moses is not allowed to enter because he mistakenly behaved in a way that undermined God’s sovereign will. In Num. 20:7-12, we witness the tragic incident when he “hit” the rock to bring forth water for the Israelites, (as he did forty years earlier), instead of “speaking” to the rock, as God had commanded him to do—which would have produced the same desired result with water miraculously pouring forth.

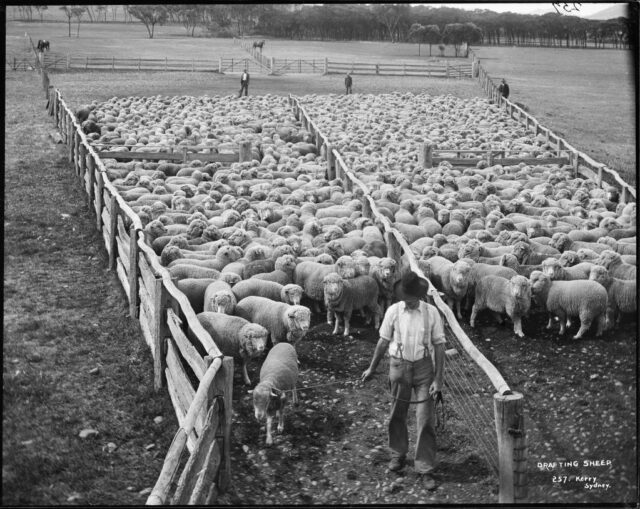

Moses has attempted several times to convince the Eternal to annul the edict, but when he finally accepts his fate, he asks something else of God. In Num. 27:15-17, we read, “Moses spoke to the Eternal, saying: ‘Let the Eternal, Source of the breath of all flesh, appoint someone over the community, who shall go out before them and come in before them, and who shall take them out and bring them in, so that the Eternal’s community may not be like sheep that have no shepherd for them.’”[1]

When Moses first encountered the Eternal at the burning bush forty years prior, he was shepherding his father-in-law Jethro’s flock (Exod. 3:1). God called Moses to move from shepherding sheep to shepherding the Israelites. Now Moses beseeches the Divine to appoint a new leader that will continue his tradition of shepherd leadership. He petitions God to choose a successor who likewise will lead by being in service to their followers—what Robert K. Greenleaf (twentieth c., United States) refers to as “servant leadership.”[2] And God approvingly accepts Moses’ request!

Acknowledging that Moses’ appeal comes across as considerably less than humble (a point several commentators raise), the Or Ha-Hayyim (Hayyim ibn Attar, eighteenth c., Morocco and Jerusalem) holds that, through the lens of the shepherd about to bid farewell to his flock, Moses’ concern is fitting: “It seems inappropriate for Moses to have addressed God in such a forward way . . . [but in truth] Moses’ entire speech reflected only his love and compassion for his people.”[3] Because Moses sees his role as being in service, he feels required to advocate on behalf of his people, regardless of what may seem as an affront to others— including, here, even God.

Rashi (Shlomo Yitzhaki, eleventh c., France) explores an additional requirement of the Torah’s understanding of servant leadership by commenting on the phrase “source of the breath” in the verse, “Source of the breath of all flesh.” Quoting a midrashic teaching, Rashi suggests: “Moses said to God: ‘Master of the Universe, the personality of each person is revealed to you, and no two are alike. Appoint over them a leader who will bear each person according to their individual character.’”[4] It appears that Rashi understands the word in the verse ruhot, literally “spirits,” as in “the spirits of all flesh,” to connect with the word for soul, neshamah, sharing the same Hebrew root as breath—neshimah. Hence, the “source of the breath/soul of all flesh” teaches that while our bodies may appear similar to each other, how we express our souls remains unique to each individual person—just as no two people breathe the same. We can now understand why Rashi concludes that this phrase expresses Moses’ leadership as calibrated to support each of the individual people he leads.

Addressing a third component of servant leadership that Moses embodies, Rabbeinu Bahya (Bahya ben Asher ibn Halawa, thirteenth-fourteenth c., Spain) comments on the need for a leader “who shall go out before them and come in before them” (Num. 27:17) as meaning that the leader personally, and not anyone else, must always be in the front, “and not as the way of the kings of the nations who remain at home and send their armies to battle.”[5] Moses exemplifies this by leading the Israelite armies during the battles along their journey to the Promised Land. More broadly, as a shepherd leader, he models to the people the behavior that the Eternal expects of them.

To summarize, these commentators, considered together, suggest that in the Torah’s conception, “shepherd leadership” calls for a leader 1) that unconditionally advocates steadfastly on behalf of their followers, 2) that honors each person’s unique personality, and 3) that leads by example.

A Missed Opportunity

R. Jonathan Sacks, (twentieth–twenty-first c., U.K.) builds on this original understanding of shepherd leadership when he writes,

Each age produces its leaders, and each leader is a function of an age. There may be—indeed there are—certain timeless truths about leadership. 1) A leader must have courage and integrity and 2) He or she must be able to relate to each individual according to their distinctive needs. But these are necessary, not sufficient, conditions. A leader must be sensitive to the call of the hour—this hour, this generation, this chapter in the long story of a people. And because he or she is of a specific generation, even the greatest leader cannot meet the challenges of a different generation. That is not a failing. It is the existential condition of humanity.[6]

While sharing common ideas with the above classical commentaries, R. Sacks opines that leadership also needs to be “sensitive to the call of the hour—this hour, this generation, this chapter in the long story of a people.” This innovative idea may have touched on what I would argue much of contemporary leadership lacks the most — relevancy, both in its methodology and content. The lack of leadership rising to the occasion results in an unfortunate missed opportunity.

Let us be careful, though, not to judge this missed opportunity as ill-intended or malicious behavior. When commenting on the tragic incident in Numbers 20:7-12, when Moses hit the rock rather than spoke to it as he was commanded, R. Sacks comments

Moses’ inability to hear this distinction was not a failing, still less was it a sin. It was an inescapable consequence of the fact that he was mortal. The fact that at a moment of crisis Moses reverted to an act that had been appropriate forty years before showed that time had come for the leadership to be handed on to a new generation. It is a sign of his greatness that Moses, too, recognized this fact and took the initiative in asking God to appoint a successor… The fact that Moses was not destined to enter the promised land was not a punishment but the very condition of his (and our) mortality.[7]

I suspect that much of contemporary Jewish leadership finds itself in a similar situation. This beckons us to consider what it is we seek in our leaders to alleviate much of our growing despair, frustration, and disappointment. In fact, many people, and increasingly so, do feel leaderless. Moses himself worried that his own flock would experience a similar feeling, so much so that he implored the Eternal, when choosing his replacement, to do so in such a way “so that God’s community may not be like sheep that have no shepherd for them” (Num. 27:17).

How can we address this modern dilemma: that a growing number of Jews relate neither to most of our leaders’ style of leadership— ‘hitting’ the rock rather than ‘speaking’ to it — nor to its message. I am concerned that, at one end of the contemporary leadership spectrum, I witness excessive emphasis on external observance of the halakhah—Jewish Law—and, equally so, at the other end, I see excessive emphasis on rejecting its legitimacy or relevancy. The all-too-common style in which leaders view their role as convincing their disciples to “fall in line” in one way or another, to the degree that they robotically adopt their ideas, succinctly expresses the reason for leaders’ increasing ineffectiveness.

The Call of the Hour

R. Moshe Rothenberg, (twentieth c., Warsaw and New York) suggests that “the leader, the rebbe, must know the souls of each and every one, and know the service that pertains to that soul, and draw them near and connect them to their root-source. This is what it means when Rashi comments: ‘appoint a leader who can bear each person according to their individual character’, i.e., their soul, to draw them near and connect them to their root-source, each and every one according to their soul.”[8]

Adding to what may appear as an innovative, even radical, understanding of the call to leadership, contemporary Israeli scholar Michael Rosen describes the approach of Reb Simhah Bunim (eighteenth-nineteenth c., Poland) in these terms:

…the zaddik as teacher was essentially a living paradigm… who endeavored to help the student fulfill his own potential. Under no circumstance was the disciple under any obligation to abrogate his own personality or responsibility to the zaddik. On the contrary, the role of the teacher was to help the disciple develop his own sense of judgment and discrimination, to develop his own sense of autonomy.[9]

When we weave all these ideas together, might we identify a common denominator shared by all? I would argue yes—they all address different shades of a type of leadership that currently is sorely missing and urgently necessary. What I ask of leadership today may appear as a new and even foreign approach. I would argue to the contrary. In fact, the call for a different leadership style today requires us to reclaim what has already been historically documented as having existed before— but for too long has been ignored.

In contemporary times, a leader’s role demands dedicated service to someone else’s life journey and recognition of each person’s unique spiritual self. This compassionate type of “shepherd leadership” focuses less on flexing power and more on inspiring and being in service. Shepherding a disciple to their own internal awareness of their soul and unique purpose in life must now take priority over emphasizing the expectation to conform to a common external behavior. Might it be that guiding a person to encounter the inner Divine spark of their soul dwelling within demonstrates the most important aspect of reclaiming shepherd leadership?

Furthermore, I would suggest that it behooves our leaders today to recognize, welcome, and honor that they are called upon by our Creator to compassionately speak, listen to, and connect with their followers with more of an intimate and customized soul-to-soul connection. This call to action requires a robust, courageous, and keenly sensitive type of leadership—a mindful and deeply spiritual “shepherd leadership.” This approach can then effectively help reveal each individual’s unique Godly purpose.

While, at the end of his life, Moses’ understanding of his flock may have displayed a lack of “sensitivity to the call of the hour,” his commitment to serving as a faithful shepherd to his people never wavered nor weakened. Our contemporary leaders would benefit in no small way—as would we as their followers—by seriously considering adopting this type of traditional leadership. How refreshing and welcoming it would be if our leaders took a more personalized approach when engaging with their congregants, students, and followers. This may take the form of spiritual mentoring and guidance, providing classes that address specific issues attracting smaller focus groups, and leading by example how to view the political arena through a spiritual lens. Specifically, in the realm of education, I call on all educators, regardless of their students’ ages, to begin demonstrating a sensitivity to the “call of the hour,” whereby the students themselves feel heard and respected, allowing them to be inspired by their learning experiences. These represent just a few ideas of the paradigm shift necessary to reclaim shepherd leadership. I would argue that posturing an openness to create and innovate is the fundamental building block for this.

Or, equally so, seriously considering the possibility that the time has arrived for current leadership, recognizing its own human limitations, to hand over the baton to a new generation, or to contemporaries with a different worldview.

As I delve deeper into the idea of reclaiming “shepherd leadership,” I invite the reader to consider the possibility that each of us possesses our own personal inner shepherd—the internal still, small voice that leads and shepherds us along our life path.

The Personal Spiritual Practice

In the Zohar, the Rabbis usually do not refer to Moses by the customary honorific Moshe Rabbeinu (“Moses our Rabbi”) but as Ra’aya Meheimena (“the faithful shepherd”). A flock of sheep needs a shepherd to direct them to pasture, and we human beings need our own shepherds to guide and inspire us.

The Piaseczner Rebbe (Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, twentieth c., Poland) opens the window of awareness of our inner shepherd by first directing our attention to a more nuanced understanding of lifneihem (“before them,” or alternatively “within them”) in our verse, “who shall go out before them and come in before them”:

This is the meaning of Moses’ plea for a leader who can clearly set out before them what they need to internally understand in order to actualize their potential awareness from within them of what they need to know at any given moment. . . . [a leader] who will lead them by modeling for them how best to use their individual intelligence wisely. The extra emphasis placed on the phrase “for them” [at the end of the verse] means ensuring that each person inside of themselves possesses their own internal shepherd. The [outer] shepherd must enter inside, into the depths of each person, strengthening their faith in the Eternal.[10]

By translating the word la-hem at the end of the verse as “for/to them,” the Piaseczner captures the enigmatic quality inherent in shepherd leadership. One who shepherds one’s followers to discover their own inner shepherd has mastered the calling of servant leadership. The leader leads the follower to the follower’s own internal leadership!

Developing this idea, I would suggest that the Piaseczner believes we all possess the capacity to discover and encounter our unique internal “shepherd leadership.” The leader within us gently, yet clearly, indicates to us how to move along our life journey, with an inner, ephemeral tugging. Some of us may experience our internal shepherd as intuition, a sort of sixth sense by which we immediately and mysteriously understand or know something without conscious reasoning.

Rav Kook (Avraham Yitzhak Ha-Kohen Kook, twentieth c., Jerusalem) considers “the unique sense of intuition, which derives from the depths of one’s personality” as “the spiritual sense . . . through which it is possible to sense God.”[11]

Like Moses, our internal shepherd—if we develop it—can lead us in the three ways discussed earlier: 1) to honor our unique personality, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach to living our lives; 2) to advocate on our own behalf regardless of undesirable consequences; and 3) to mindfully model what we sense the Divine Presence is asking specifically of us in all our uniqueness.

The third aspect in particular renders this as a spiritual practice, with Moses again as our model. When Moses encounters God at the burning bush (Exod. 3:1–10), the Divine appoints him as the shepherd who will lead his flock out of Egyptian slavery—essentially transforming Moses’ responsibility for literal sheep into the sacred act of shepherding the Jewish people. Before this divine encounter, Moses could honor, and advocate for, himself (the first two of the three components). However, this third element requires him, and, by extension, us as well, to realize and then act upon the realization that our inner shepherd is in fact the Divine shepherding us to sacred action.

Yet to uncover and actualize our inner shepherd seems to require an impetus toward self-agency that is not necessarily familiar to all of us. The Piaseczner observes that many of his own disciples (Warsaw Jews during the interwar period) lack this quality: “People are always bemoaning, sighing, ‘Where is my freedom of choice? I feel so imprisoned . . . that it is almost impossible to control myself, to choose between what to want and what to deem as loathsome’.”[12]

He then suggests the root cause of these symptoms:

For every choice that emerges from an individual’s will, rather than reflecting someone else’s will [making the choice], there first must be a person who is choosing for themselves [rather than relying on another’s choice]. There must be an individuated person—a distinguishable self—who can decide what they want for themselves. But if there is no individuated person—a distinguishable self—just one among the species, there can be no free choice or personal will. Because who will choose, if, besides the herd mentality, there is nothing there at all?[13]

The Piaseczner now writes his prescription:

So, gaze into your soul. Are you bringing forth your true real self? Are you an individuated person . . . ? Or are you just a member of the species, the human species? . . . A person must distinguish themselves with the qualitative essence of who they really are: not only must they not remain imprisoned by social rules, cultural customs, or accepted thought without the ability to see beyond them, but they must also have a mind of their own. . . . This means revealing one’s own personality and unique sense of self that is within you—that which depicts your very self.[14]

With this understanding, all three phases of internal shepherd leadership may now be seen as both a realistic and yet uplifting spiritual practice. To “distinguish [ourselves] with the qualitative essence of who [we] really are,” the Piaseczner’s prescription directs us to encounter our soul, the Divine Presence within each of us—and, as Rav Kook mentions, to experience this intuitively, meaning to sense this as Godly awareness.

Similarly, when we advocate on our own behalf, we can introduce our Godly selves into the world ‘at all costs’—in our own vulnerability and transparency. Like Moses commanding in the name of the Eternal, as if the Eternal is moving resoundingly through him, “Let My people go!” (Exod. 5:1), we might imagine ourselves advocating for a vital objective with nearly commensurate clarity, power, and sense of purpose. When we infuse our intuitive awareness into our actions, led by our internal shepherd, we hallow the moment as Godly.

In all, by being faithful to our inner shepherd’s leadership, we may model to ourselves and others how to help bring the world to a more redeemed place. Expressing our unique selves and advocating for what we believe the Divine is asking of us, we step forward and try to model it to all. The shepherd within seems to be calling us to spiritual activism, to become agents of sacred change. Part of this spiritual paradigm shift includes recognizing that each of us possesses shepherd leadership, even if this awareness is buried. The shepherd in me hopes to encourage and activate the shepherd in you, as I hope the shepherd in you will do the same for me.

[1] All Tanakh translations are from the JPS 2023 edition, with minor modifications.

[2] Robert K. Greenleaf, “What Is Servant Leadership?,” 2021, Robert K. Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership, www.greenleaf.org/what-is-servant-leadership.

[3] Or Ha-Hayyim to Num. 27:15, s.v. “va-yedabber Moshe.” Writer’s translation.

[4] Rashi to Num. 27:16, s.v. “Elohei ha-ruhot,” pulling from Midrash Tanhuma, Pinhas 10. Writer’s translation.

[5] Rabbeinu Bahya on Num. 27:17, s.v. “asher yeitzei lifneihem.”

[6] Sacks, “Why Was Moses Not Destined to Enter the Land”, in Covenant and Conversation, Chukkat 5773 (2013), https://rabbisacks.org/covenant-conversation/chukat/why-was-moses-not-destined-to-enter-the-land/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Rabbi Moshe Rothenberg, Sefer Bikkurei Aviv, Pinhas (St. Louis, 1942) (emphasis added). Translation from Rabbi David Ackerman, “Chukkat: Each According to their Soul,” in Torah Without End: Neo-Hasidic Teachings and Practices in Honor of Rabbi Jonathan Slater, ed. Rabbi Michael Strassfeld (Ben Yehuda Press, 2022), 78-79.

[9] Michael Rosen, The Quest for Authenticity: The Thought of Reb Simhah Bunim (Urim Publications, 2008), 40.

[10] Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, Derashot Mi-Shenot Ha-Za’am [Heb.], ed. Daniel Reiser (Herzog Academic College and Yad VaShem, 2017), 148 (writer’s translation) (emphasis added).

[11] Shemoneh Kevatzim, 3:81. The writer’s translation takes liberties for this interpretation.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.