Moshe Kurtz

The Talmud records an opinion that Moshe Rabbeinu wrote the final words of the Torah in tears (Menahot 30a and Bava Batra 15a). And while only Moshe Rabbeinu could have the benefit of God dictating the words to him when he lacked composure, I pray that God will help guide my hand to eulogize my rebbe, Rabbi Dr. Moshe Dovid Tendler zt”l.

I always advise my congregants when they lose a loved one that during sha’at himum (when the pain is fresh) it is nearly impossible to adequately eulogize their dearly departed. Nonetheless, there is a value in sharing what we can muster with the short notice that we are granted.

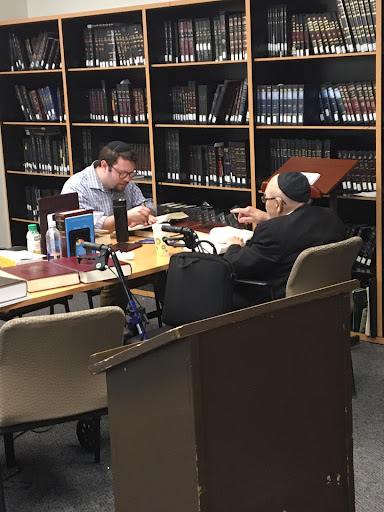

Rav Tendler, thank God, lived a long and fulfilling life. One might even say that now is actually a time to celebrate his legacy and impact. However, it still remains challenging for me to internalize that reality because I was granted merely the last three years with him – and so, for completely selfish reasons, I have a difficult time coming to terms with his loss. Nevertheless we spent considerable time together during this final chapter of his life. In fact, I spent one of those years learning with Rav Tendler in what could be best termed a one-to-one “chavrusa” experience, despite the unfathomable disparity between us in Torah and general erudition. During these moments, I had the immense privilege of a sustained private interaction with Rav Tendler. Thus, while I am certainly not an authority on Rav Tendler’s Halakhah and philosophy, I did have access to some exclusive insights and experiences.

Many have already summarized the Torah and academic achievements of Rav Tendler, in which they highlight his most well-known positions such as his opposition to the kashrut of swordfish, his insistence upon the rediscovery of tekhelet, and, of course, defining brain death as synonymous with the moment of halakhic death. In addition to Rav Tendler’s personal positions, he offered unique glimpses into the mind of his esteemed father-in-law Rav Moshe Feinstein. In some instances, Rav Tendler wrote these insights publicly, such as his article in the Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem’s publication Le-Torah Ve-Hora’ah: Sefer Zikaron Le-Maran Ha-Gaon Rav Moshe Feinstein, where he delves into the halakhic analysis behind Rav Moshe’s landmark decision to proceed with separating conjoined twins.

Yet being a student also gave me a unique glimpse into issues that were never published. For instance, I once inquired why Rav Moshe did not accept his own rationale to drink halav stam as recorded in Igrot Moshe (Yoreh De’ah 1:47). Rav Tendler replied that of course Rav Moshe believed in his own heter; in fact, many of the members of his own household relied upon it! Rather, Rav Tendler explained, Rav Moshe’s true concern was that before he moved to America he had maintained the minhag to avoid halav stam, and he would never annul a minhag if possible. This position was based on the Talmudic account (Ketubot 77b) of R. Yehoshua ben Levi defying the Angel of Death and being permitted to remain alive in The Garden of Eden because he never annulled a vow. (This explanation is novel and perplexing, as it does not seem to comport with the end of the responsum where Rav Moshe advises conscientious individuals to continue avoiding halav stam. R. Shimshon Nadel told me that Rav Tendler believed that Rav Moshe was motivated to add this qualification out of sensitivity and concern for those in the industry who sacrificed and made it their livelihood to provide halav yisrael for the Jewish people.)

Another edifying experience took place about two years ago when I began my rabbinic job search. At the time, Rav Tendler and I were learning “bechavrusa.” When I told Rav Tendler that I would soon be entering the rabbinate, he strongly recommended that we study what he considered to be the most critical responsa of Igrot Moshe to prepare me for the practical issues I would face in the pulpit. Unfortunately, we never made it through all the responsa that Rav Tendler had planned, but he was kind enough to write them down and have his aide scan them for me.

While Rav Tendler had the utmost reverence for his father-in-law, he did not let that get in the way of his unquenchable quest for truth. And so, on the rare occasion that he disagreed with Rav Moshe, he did so respectfully and with little equivocation. For instance, Rav Tendler thought that Rav Moshe (Igrot Moshe, Orah Hayyim 1:99) took it a step too far when he classified those who keep their shul parking lots open and encourage people who will inevitably drive on Shabbat to attend as being a meisit (inciter, generally of idolatry) – far worse than the standard violation of lifnei iver. I remarked that I was glad to hear that Rebbe thought that, because my current shul has an open parking lot! (See Responsa Minhat Shlomo 1:31:1 and Be-Ohalah Shel Torah, Orah Hayyim 5:22 for justifications.)

After I had developed sufficient rapport with Rav Tendler, I wanted to find out how he met his wife Shifra, daughter of Rav Moshe Feinstein. But I was still a little bashful, so I phrased it as, “How did Rebbe become connected with Rav Moshe?” Rav Tendler immediately intuited what I was asking and related to me the following story: Apparently, back in the day, there was a library in the Lower East Side where all the Jewish kids would go to hang out. One day, when Rav Tendler was studying biology, a young woman approached him to ask a “shaylah” in what she was studying. This woman was none other than Shifra Feinstein.

Now, Rav Moshe and Rav Tendler’s father were both colleagues, and in some instances they even sat together on the same beit din. Some time in the future Rav Moshe inquired of Rav Tendler’s father whether there was an interest to make a shiddukh between their children. When Rav Tendler was asked by his father if he would be amenable to such an arrangement, Rav Tendler replied that he appreciated the suggestion but he had already begun to pursue the idea on his own!

On a more poignant note, at the funeral, a number of the family members noted that Rav Tendler passed away on Shemini Atzeret, the very same day as his wife’s birthday. They pointed out that while tzadikkim are known to die on the same day they are born, perhaps God had arranged that Rav Tendler and his rebbetzin should be appropriately reunited as the ultimate birthday present for their savta. Indeed, he was reunited with the second half of his neshamah that had been born on that very day.

—

Rebbe was well known for his firmness and resolute nature. Even at age 93 he was working with a group of rabbis to combat liberal movements and ensure that the State of Israel retained some form of Orthodox halakhic family and identity standards. This was not, however, a contradiction to his gentleness and humility.

In preparation for my pulpit interviews, I prepared a class on the topic ha-hakham she-asar ein haveiro rashai le-hatir (see Niddah 20b and Avodah Zarah 7a), which is essentially the Talmudic principle against “shopping for a heter.” Rav Tendler apparently adopted the opinion that the issue of a second rabbi contradicting the first rabbi’s pesak was due to the affront caused to the initial rabbi’s dignity (see Rashi, Niddah 20b s.v. “mei-ikarah”; Rosh, Avodah Zarah 1:3 for an opposing view). It would follow accordingly that the first rabbi may grant permission to the enquirer to seek a second opinion.

For example, when I brought up Rav Moshe’s hardline responsum on abortion (Igrot Moshe, Hoshen Mishpat 2:69), Rav Tendler told me that it might be best if I don’t come to him if I want a more lenient pesak. He did not back down on his beliefs, but he indicated that if needed I may seek recourse for my future congregants elsewhere. This demonstrated to me that the source of Rav Tendler’s forceful nature came not from a place of pride, God forbid, but from a passion for seeking and propounding what he understood to be the truth. However, Rav Tendler once remarked to me that he feared that he had been too harsh with some people and perhaps that is why Hashem sent him certain yisurin (tribulations). He would always say in Yiddish, “es zel zayn a kaparah” – whatever challenge God sends my way should serve as an atonement for my transgressions.

The importance of developing a well-grounded and sensitive outlook did not merely manifest in deed, but in Rav Tendler’s choice of study as well. Even though our primary sefarim were the Gemara, Shulhan Arukh, and Eglei Tal, Rav Tendler always consecrated time to teach Midrash Rabbah on Thursdays. He lamented how this magnum opus of our traditon’s wisdom had become mostly neglected. He stressed the importance of internalizing both the Halakhah as well as the ethics that our Sages offer us.

Indeed, while Rav Tendler was very conscientious about making the most of our time during shiur, he would answer the phone if there was a matter that he suspected to be urgent. On one occasion, Rav Tendler had just been informed that one of the RIETS staff members had a grandchild who was in the NICU at Hadassah Hospital in Israel. Upon hearing this, he immediately got on the phone with his granddaughter who works as a doctor there and had her check in on the family to offer support. This act of kindness gave the family back in America a measure of hope and reassurance.

Due to the need for me to balance my other responsibilities with my “chavrusa” with Rav Tendler there were days that I had no lunch break. Thankfully, Rebbe was very understanding of my schedule and was amenable to my bringing lunch to our learning sessions. Every day I came with my Tupperware box of Honey Bunches of Oats and a thermos of milk packed from home. One time, I could not open the thermos, and noticing my struggles, Rav Tendler (who was 93 years old!) reached over and began to loosen the thermos open for me. And while he did not succeed, he had loosened it just enough that I was able to do the makeh be-patish! How many elderly roshei yeshiva would do that? It was the small moments like these that made Rav Tendler feel less like an imposing Rosh Yeshiva and more like a grandfatherly figure.

That same year, the university staff moved Rav Tendler’s sefarim to his new office and simply left them in huge boxes blocking off most of the room. I offered to help him sort the sefarim during my limited breaktime, but he was adamant that it would not be right for me to perform labor if YU would not compensate me for my time. I was deeply impressed with Rebbe’s principle and integrity. He did not want to come anywhere close to taking advantage of a willing helper.

—

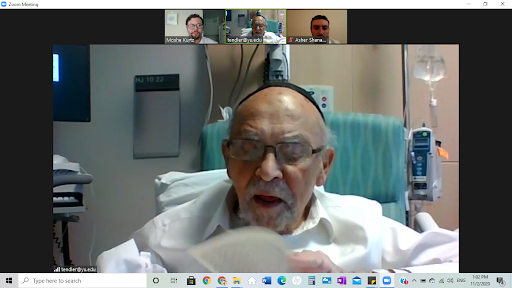

After the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States, there was about a month when Rav Tendler did not yet have access to Zoom as he needed help setting up his computer (he was then 94 years old!) and instead called me on the phone. During this interim Zoom-less period, Rav Tendler shared with me the halakhic and communal challenges that he was attempting to navigate. He very badly wanted to reopen his shul, but the current public health guidance was to remain home. And while, of course, he complied, it still proved to be a heart-wrenching decision for him. Before the first Pesah of COVID-19, Rav Tendler reached out to bounce an idea off me. As is the custom, community members who wish to sell their hametz will designate their rabbi via a shtar harsha’ah, a document that grants the rabbi power of attorney. Generally, the congregant concretizes this appointment by lifting the rabbi’s handkerchief or pen. However, in order to prevent unnecessary interactions, Rav Tendler asked me if I thought that having his congregants drop off the document in his mailbox would be acceptable under the circumstances. While Rav Tendler clearly knew what he was doing, I was delighted and impressed that he double-checked his ideas with me, his student! This demonstrated a clear act of humility and willingness to seek the truth, regardless of the source.

—

My wife Marisa also had the opportunity to meet Rav Tendler. In 2019, we both learned together with Rav Tendler in his office at YU. And it was one of my most treasured moments. When we had finished our learning for the day, I asked if I could take a photo of the three of us. Before I could press the button on my phone, Rav Tendler interjected and instructed Marisa to keep her Gemara open. He explained that when people see this photo they should know that women can learn Gemara too!

Rav Tendler was very forthright about what he believed to be the Torah’s view on women, people who identify as LGBT, and a host of social matters. For instance, he often asked me, “nu, what is your wife cooking for you this Shabbos?” (One time he even chided Marisa for making chicken for Pesah – he exclaimed that such a holiday deserves meat!) Nonetheless, like his Rebbe Rav Soloveitchik, he propounded that women should also learn Gemara in order to appreciate the depth and sophistication that our rabbinic tradition has to offer. This, in his view, was not at odds with the gender norms that he saw as an obvious part of Judaism (no different than how Rav Moshe addressed the matter in Igrot Moshe, Orah Hayyim 4:49).

Indeed, Rav Tendler did not see the differentiation of roles as an excuse to disrespect women. Rather, he argued that a man is supposed to give due honor to his wife. One time, in the middle of our Zoom learning, he noticed that I was suddenly distracted and inquired if everything was alright. I told him that Marisa had just come home from running errands and that I had given her a quick greeting. Rav Tendler responded to me, “That’s it? When your wife comes in the door you are obligated to stand up for her!” Marisa still doesn’t let me do that for her, but I try to take the moral of Rav Tendler’s point to heart.

—

R. Akiva once lamented to his student, R. Shimon bar Yohai, “More than the calf wants to suckle, the cow desires to nurse [its calf]” (Pesahim 112a). During Rav Tendler’s final months in this world, he was constantly being discharged and then returned to the hospital for surgeries and long visits to the ICU. There was a significant lapse since I had last been able to speak to him, until one night, when I was at a close friend’s wedding, I received a call. “It’s Rebbe!” I exclaimed, and I ran outside the hall immediately to take the call. Everyone else at the table could not understand what had come over me, but it didn’t matter. It had been so long since I last heard my Rebbe’s voice, and I was eager to speak to him once more. But, to my great dismay, it was a very challenging conversation and I struggled exceedingly to make out the words that Rav Tendler was attempting to articulate. However, there was one sentence that I could fully understand – the one that he kept repeating over and over again: “The seder ha-limmud…Moshe, what’s going to be with our seder ha-limmud?” And those were the final words I remember him uttering to me. Even in our final conversation, all Rav Tendler could focus on was getting back to our regular learning as if nothing had changed. “What’s going to be with our seder ha-limmud?”

Alas, our seder ha-limmud has come to a solemn end. But I am left with the indelible impression that rebbe gave me. In his final days all he could think about was how he could continue to teach and nurture his students. As his family remarked to me after his passing, that is what made him persist for as long as he did. יוֹתֵר מִמַּה שֶּׁהָעֵגֶל רוֹצֶה לִינַק פָּרָה רוֹצֶה לְהָנִיק

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.