Wendy Zierler

Haim Gouri, “I Live at This Time in an Old Book” (2015, Rona Kenan, music)[1]

| I Live at this Time in an Old Book I live at this time in an old book. I live at this time in the right environment That exports oranges and sighs To half the world. |

אני גר כעת בספר ישן אֲנִי גָר כָּעֵת בְּסֵפֶר יָשָׁן. אֲנִי גָר כָּעֵת בַּסְּבִיבָה הַנְּכוֹנָה הַמְיַצֵּאת תַּפּוּזִים וַאֲנָחוֹת לְמַחֲצִית הָעוֹלָם. |

| I live right now in a white city Filled with black dreams. I live amid rare predictions And unexpected conditional sentences. |

אֲנִי גָר כָּעֵת בְּעִיר לְבָנָה וּמְלֵאַת חֲלוֹמוֹת שְׁחֹרִים. אֲנִי גָר בֵּין הַשְׁעָרוֹת נְדִירוֹת .וּמִשְׁפְּטֵי תְּנַאי בִּלְתִּי-מְשֹׁעָרִים |

| I move like a passing shadow[2] On a street unlike any other street, Amid hearts on the verge of breaking[3] Toward the kingdom always coming in the future. |

אֲנִי נָע כְּצֵל עוֹבֵר בִּרְחוֹב שֶׁאֵין דּוֹמֶה לוֹ בָּרְחוֹבוֹת, בֵּין לְבָבוֹת הַמְחַשְּׁבִים לְהִשָּׁבֵר .אֶל הַמַּלְכוּת הָעֲתִידָה תָּמִיד לָבוֹא |

I move between holy people And the lovesick.[4] I see women and men Returning from the world to come. |

אֲנִי נָע בֵּין אֲנָשִׁים קְדוֹשִׁים וְחוֹלֵי אַהֲבָה. אֲנִי רוֹאֶה נָשִׁים וַאֲנָשִׁים .הַשָּׁבִים מִן הָעוֹלָם הַבָּא |

Every Tuesday at the end of morning minyan at my local synagogue in Riverdale, New York, I offer a mini-class entitled “Shir Hadash shel Yom”―“New Poem of the Day,” in which I teach a modern Hebrew poem that speaks either to matters of the day or of prayer. Over the past seven months in the “Shir Hadash,” we have shuttled back and forth between poems and songs written several decades ago and those written just recently in response to the October 7 attack. Many of the older poems date back to the 1948 War and yet have felt eerily relevant and timely. In recent months, it has felt as if time has folded back on itself, the antisemitism of earlier generations and the attacks on the once fledgling State of Israel taking on a terrifyingly resurgent new life. How could it be, we wonder, that all this time has passed, and yet here we are again, back in tragic, insecure times? Doesn’t anything ever get any better?

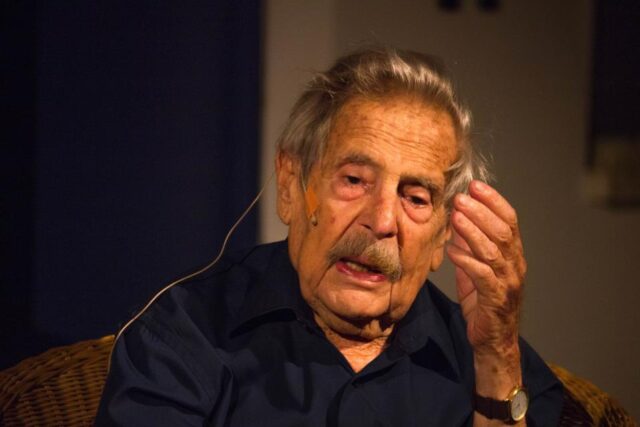

Haim Gouri, famous for providing the lyrics for Yitzhak Rabin’s favorite song “Ha-Reʿut,” is a bridge figure connecting the old and the more recent because of when he came into prominence (the 1948 War), how long he lived, and how he continued to write and publish well into his 90s. Gouri died in 2018, so he has not been around to lyricize this present war. But almost to the very end of his life he was writing and publishing; the above poem by Gouri explicitly engages longevity and old age as a way of bewailing and offering perspective, even hope, in the face of the ongoing woes of Israel and the Jewish people.

The poem is worth reading, if nothing else, for its opening line that speaks both to issues of old age and the Jewish/Israeli relationship with textuality. If our bodies can be likened to books that are opened and read, the body that Haim Gouri inhabited at the time of this poem’s writing―when he was 92 years old―was indeed old. The State of Israel, too, though a relatively young country, resides in a very old and established (nekhonah) historical environment, endowing every experience and event with layers of historical significance and resonance. And insofar as our classical sources have recorded and continue to inform the significance of this environment, the entire country and its contemporary inhabitants live “in an old book,” rendering the people and the land old and new simultaneously.

Gouri’s opening declaration that he lives in an old book also recalls, for me, an illustration that appeared at the head of a 1920 story by S.Y. Agnon entitled “Maʿaseh Rabbi Gadiel ha-Tinok” (“The Tale of Little Rabbi Gadiel,” 1920/1925).[5] Agnon’s story, which served as the basis of Sadie Rose Weilerstein’s K’tonton series, is a Jewish version of “The History of Tom Thumb,” an Arthurian legend dating back to 1620. The story describes a plowman and his wife who yearn so deeply for a child that when visited by the great magician Merlin (who is dressed up like a beggar, like Elijah the prophet in so many Jewish folktales), they say they’d be happy if that child were no larger than his father’s thumb. This is exactly what Merlin gives them, a tiny son named Tom (a name close in sound to Thumb). Agnon’s “R. Gadiel” transforms the tiny, adventurous, and wily Arthurian Tom Thumb into a young Torah prodigy who also serves as an advocate (and martyr, as gedi-El translates to “lamb of God”) for Jews in times of persecution.

Like his Arthurian model, R. Gadiel is vulnerable to dangers and given to mishaps: falling into a vial of Hanukkah oil, or sitting atop and accidentally getting shut into the pages of a book that his father had been studying, as seen in the illustration included at the top of the original 1920 printing of the story.[6]

Against all odds, and despite his tininess and vulnerability—a metaphor for the minority status of the Jewish people as a whole—R. Gadiel saves his family and people on Passover from a murderous blood-libel plot and lives on miraculously—never entirely growing up or old—ever ready to advocate for the Jewish people against their evil detractors. As such, he lives in an old book of Jewish suffering, particularity, and purpose.

Against all odds, and despite his tininess and vulnerability—a metaphor for the minority status of the Jewish people as a whole—R. Gadiel saves his family and people on Passover from a murderous blood-libel plot and lives on miraculously—never entirely growing up or old—ever ready to advocate for the Jewish people against their evil detractors. As such, he lives in an old book of Jewish suffering, particularity, and purpose.

The speaker in Haim Gouri’s poem takes on a similar role—living in the old book/land of Jewish history—that is constantly threatened and yet continues to dream of redemption.

As a reflection on living in this old country/book, Gouri’s poem comprises a study of opposites. His speaker lives in a country that exports oranges and sighs, in a white city with black dreams.

High Holiday liturgy, with its contrasting intimations of mortality as well as its hopes for the New Year and for the Kingdom of God, hovers over the poem—especially in the third stanza, where the poet pictures himself moving like a “tzel over” (“passing shadow”), an allusion to Psalms 144:4 as quoted in the “Unetaneh Tokef” prayer. He describes himself as moving along peerless streets, among hearts on the verge of breaking (ha-mehashvim le-hishaver), an allusion to the condition of the boat on which the prophet Jonah escapes in the midst of a dangerous storm sent by God (Jonah 1:4). Here, of course, it is not a boat but hearts that are continually breaking from disappointed hopes and yet always hoping and moving toward an Aleinu-like repaired and perfected Commonwealth.

As to the meaning of the last stanza of this poem, which refers to seeing men and women who have returned from “olam ha-ba,” I’ll offer a few different possible interpretations. The poem was published in 2015, a year after the kidnapping of three Israeli teenagers—Naftali Fraenkel, Gilad Shaer, and Eyal Yifrah—on June 12, 2014, and the launching of the 2014 Gaza War on July 8, labeled “Operation Protective Edge.” Reading about that conflict ten years later feels very much like living in an old book.

Is the image of men and women returning from olam ha-ba a reference to young male and female soldiers somehow returning safely from the mortal dangers of the battlefield?

Is it a statement of disillusionment on the part of those like Gouri, who had always nursed hopes for peace and a future world to come but were now facing a national turning-away from any expectation of a two-state solution? The results of the 2015 early election, which sent Netanyahu back to power, might support that reading.

Is the speaker marveling here that, despite the renewed conflict and worry, holy, lovesick Israel (as in the imagery of Yedid Nefesh) somehow manages to replenish its spirit on a weekly basis through the “meʿein olam ha-ba,” the like-the-world-to-come of Shabbat, with men and women returning weekly to their workaday lives and worries?

Is Gouri reflecting on the tenuous nature of life, especially for someone his age, where health emergencies repeatedly place you on that razor-thin line between this world or the next? Each time an elderly person is sent to the hospital and then discharged might be seen like a return to this world from the world to come.

Or perhaps, reflecting on his own mortality and the life he has lived inside of the book(s) of classical Jewish tradition and Hebrew poetry, Gouri is acknowledging the influence and inspiration of all the dead male and female poets and expressing the hope that his own poems will do the same for others?

Like I said, I call my weekly class “Shir Hadash shel Yom” (“New Poem of the Day”), but perhaps in honor of Gouri’s poem, I should rename it “Shir Yashan shel Yom” (“Old Poem of the Day”), so as to acknowledge, similarly, with gratitude, the opportunity at this time, to live in the old book of Gouri’s poetry, and to receive, if just briefly, his message from the world to come.

[1] Kenan’s musical adaptation is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGzhRiHvyGI.

[2] Cf. Psalms 144:4.

[3] Cf. Jonah 1:4.

[4] Cf. Song of Songs 5:8.

[5] Included in S.Y. Agnon, Elu Ve-Elu, vol. 2 (Tel Aviv: Schocken, 1959), 416-420.

[6] The illustration, attributed to S. Raskin, appeared in Miklat 4:10-12 (1920): 406.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.