Naama Sadan

Introduction

We live in a world marked by ongoing crises, and the strategies celebrated for addressing them tend to emphasize overt action, dominance, and rapid response.[1] Approaches traditionally associated with women—what might be termed “female-coded” actions—are frequently overlooked, despite their potential to offer innovative and valuable methods for navigating challenges. For example, the essay collection All We Can Save highlights how women-led efforts in environmental stewardship—rooted in community, incremental progress, and emotional openness—have long been marginalized, even as these approaches prove crucial in times of crisis.[2]

I believe that many of us are often unaware that there is more than one way to deal with a crisis. We tend to fall back on the defaults we know. In the following reading, I aim to join the efforts to shift that tendency to overlook female-coded actions. I turn to the story of Esther as a source which can equip us with much needed inspiration for times of crisis. Two assumptions direct my exploration: First, the distinction between male-coded and female-coded actions in crisis is important, yet both are necessary.[3] Male-coded actions often emphasize direct, overt, international, and aggressive forms of engagement, whereas female-coded actions might involve nurturing, collaborative, local, and indirect approaches. Providing access to both modalities for people of all genders enriches the toolkit available for mitigating crises.

Another key assumption is the symbolic reading of myths and stories, which has long served as a method for encoding and passing down wisdom across different traditions. Carl Jung is perhaps best known for this approach in recent times, but even before him, Hasidic masters, for example, interpreted stories from the traditional canon as symbolic narratives occurring within every individual.

The story of Esther can serve as a symbolic narrative that illustrates the power of integrating both male- and female-coded modes of action. The objective here is to avoid the common reading, which finds ways to show that Esther turned into an overt activist, and to instead appreciate and value her inward mode of influencing change. This mode of action, often undervalued, is a potent form of leadership and crisis management. Esther’s story does not merely invite us to witness a transformation, but encourages us to recognize the strength in what is traditionally perceived as passivity. By reclaiming and valuing these female-coded methods, we not only broaden our understanding of what effective action looks like but also empower a more inclusive, effective approach to the challenges of contemporary life. In the following paragraphs, I seek to unpack these two modes of response to the world turning on us.

First Reading: Passive to Active

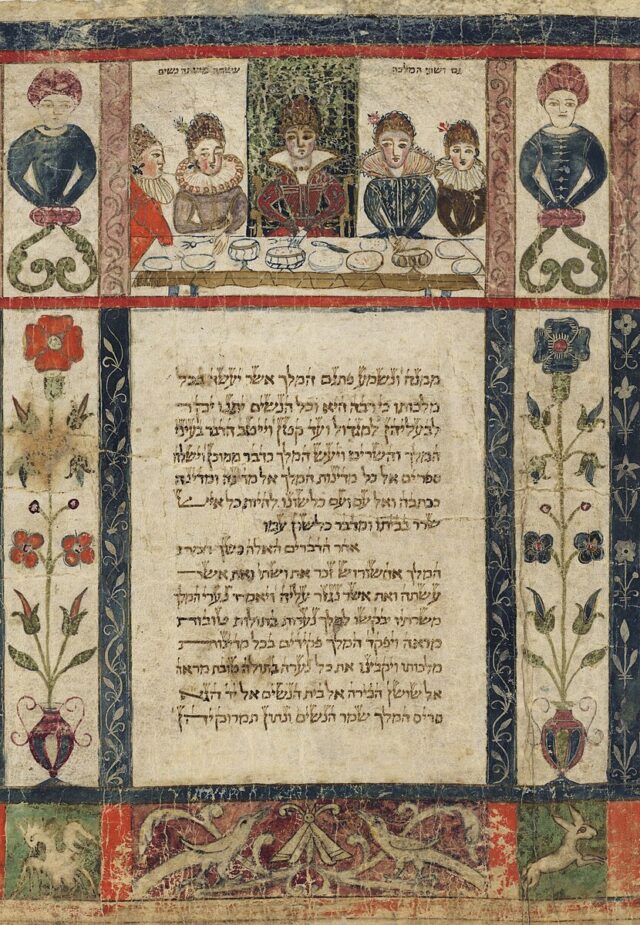

The book of Esther is read every year on Purim. It is a story of crisis, of a decree that “overnight” becomes a royal policy, which aims to destroy the Jewish people. Mordekhai and Esther, the heroes who eventually overturn the decree, are introduced in the second chapter of the book:

In the fortress [of] Shushan lived a Jew by the name of Mordekhai, son of Jair son of Shimei son of Kish, a Benjaminite. [Kish] had been exiled from Jerusalem in the group that was carried into exile along with King Jeconiah of Judah, which had been driven into exile by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. He was foster father to Hadassah—that is, Esther—his uncle’s daughter, for she had neither father nor mother. The maiden was shapely and beautiful; and when her father and mother died, Mordekhai adopted her as his own daughter. When the king’s order and edict was proclaimed, and when many girls were assembled in the fortress [of] Shushan under the supervision of Heigai, Esther too was taken into the king’s palace under the supervision of Heigai, guardian of the women. The girl found favor in his eyes and received generosity from him, and he hastened to furnish her with her cosmetics and her rations, as well as with the seven maids who were her due from the king’s palace; and he treated her and her maids with special kindness in the harem. Esther did not reveal her people or her kindred, for Mordekhai had told her not to reveal it. (Esther 2:5-10)[4]

In this passage, the Hebrew verbs that describe Mordekhai are largely active (e.g., “adopted,” “told”), while the verbs that describe Esther are all passive in form (e.g., “was taken,” “did not reveal”). While Mordekhai is introduced with a full history and lineage, Esther is introduced as an orphan without lineage.[5] Esther is presented as an extension of Mordekhai, as his dependent, with very little agency over her life. When Esther is taken to the king’s harem, she is still portrayed in relation to others, following the lead and directions of Heigai, her new “guardian.” We also learn that she is concealing her identity, thereby obeying Mordekhai’s order to not tell anyone about her Jewish origin.

Modern commentators emphasize Esther’s introduction as a passive figure, and highlight the later ‘shift’ in her personality as the important takeaway for modern readers. In a lesson plan for middle school students in the Israeli education system, for example, Dr. Gili Zivan directs the students through art interpretation and text exercises to identify the passivity of Esther in the beginning of the story as a contrast to her active new self in the later part: “The Esther of the beginning of the book is a passive, obedient Esther, a marionette doll whose strings are pulled by men in various roles. ‘Be beautiful and shut up’ is the message she receives from the environment, and she internalizes it well. In the second part of the scroll we discover a completely different Esther: active, proactive, manipulative, and a leader.”[6] Dr. Zivan defines a leader based on Esther’s so-called latter characteristics, the active ones. She also suggests a direct application of how Esther’s characterological change can inform our growth today as individuals. A similar theme of Esther’s shift from passive to active appears in the 929 Project, which serves as a major access point to biblical stories for contemporary readers.[7]

In more conservative discourse we find a similar thread: R. Aharon Lichtenstein utilizes the story of Esther’s transformation to describe the inner shift every person needs to go through in order to choose a meaningful life.[8] According to Rav Lichtenstein, Esther appears first as a passive girl who, when asked to act for her people, is selfish and apathetic, looking out for only her own needs. When Mordekhai asks her bluntly—do you care or not?—she wakes up to be the active, caring leader she could be. In this reading, too, the story is brought to the individual level: “Each one of us is required to do what Esther did: stand before himself and before God, and find out: What can I do for the people of Israel?… The question he must ask himself is not just whether what he does is good, but whether he is the best.” Both Dr. Zivan and Rav Lichtenstein bolster one norm of Jewish heroism, in which Esther shifts to become an active, commanding, and ‘strong’ leader who is actualizing her “best” self.

The interpretive readings of the Esther story that I have just outlined are very important. These darshanim are doing crucial work of meaning making: they tell a story of a woman being a leader for a world in which that reality should still not be taken for granted. They are teaching that people can shift from passive to active participation; that they can reach out, act, and change; and they are instructing us readers that we should, as individuals in society, do so. I honor and appreciate this work—which is still rare—and which empowers women and all individuals to learn from a heroine how to ‘be’ in life.

At the same time, these interpretations teach us that action, leadership, and constant work are the desirable norm. It is my impression that the book of Esther also holds another narrative for us , one that is equally pressing for our time: one that teaches us not to be afraid of so-called passivity, and to reclaim it. It teaches us to see that action and dominance are not the only ways to change the world. The actions described as passive are not ‘not-doing,’ but an active choice to wait, to not exacerbate a conflict, to work in the shadows where people don’t see. These actions require very strong leaders. They are not as popular, they support evolution and not revolution, they cool down. The narrative that I will put forth is inspired by the work of Ester Gofer, a contemporary spiritual teacher in Israel who focuses on Jewish wisdom based in seasonality and the feminine body. My interpretation of the story of Esther focuses on strength in passivity, and sheds light on Esther’s way of dealing with crisis as a parallel standard to the masculine ‘default’ approach.

Second Reading: Internally and Externally Focused Activism

Using the language of “passive” and “active” is problematic. There is an inherent judgment in how these words are interpreted in our society: active as positive and passive as negative. The alternative framing of “externally-focused activism” vs. “internally-focused activism” helps us to better unpack the story of Esther and her heroism. This language is also connected to the two types of bodies males and females inhabit; hence I use these interchangeably with “male-coded” (externally-focused activism) and “female-coded” (internally-focused activism). One of the emphases in the second wave feminist movement was attention to the female body and the experience of being in such a body. From a reproductive point of view, females ‘can do less,’ i.e., they can have a limited number of offspring, as their bodies invest a lot in the pregnancy of each offspring. The difference between the bodies is not just in the number of potential offsprings, but also in the ways they function. A male body is theoretically ready to act and achieve fertilization at any time. Unlike the male body, the female body functions in cycles. Over the course of a female body’s monthly cycle, there is only a brief window of opportunity for reproduction. For the female body to be effectively fertile, much of the time should be dedicated to rest, nourishment, and balance towards these precious few days of fertility, rather than engagement in constant activity. The menstrual cycle also includes an inherent stage of loss of potential life as well as renewal. Such different bodily experiences require acknowledgement of different forms of productivity. Passivity can thus be reframed as cyclical, internally-focused activism, a crucial part of the productive process.

Revisiting the story of Esther with new language to describe different forms of action can help us to recast the shift that many contemporary interpreters focus on as the turning point in Esther’s personality from passivity to activity. In chapter 4, Mordekhai exhibits externally-focused activism. He knows about the decree upon his people and engages in public mourning. He comes out to the palace and demands from Esther that she act. He is determined to create change through external action. When Esther, until now unaware of the crisis that has befallen her people, hesitates to act, Mordekhai famously tells her:

Do not imagine that you, of all the Jews, will escape with your life by being in the king’s palace. On the contrary; if you keep silent in this crisis, relief and deliverance will come to the Jews from another quarter, while you and your father’s house will perish. And who knows [if] perhaps you have attained to royal position for just such a crisis. (Esther 4:13-14)

Instead of acting right away, Esther resources herself with silence for just a bit longer in order to mobilize herself and create more power. In the most urgent moment, Esther chooses not to reach out with action, but rather to take three days to fast, gather the community, pray, and make space for her emotions, including being present with the possibility that she may perish. Esther creates a container for the intensity of her experience and that of her people. In doing so, she demonstrates a different approach to action. Esther’s heroism proves how internally-focused activism can be utilized to approach a crisis, making space for solutions to emerge and unfold.

Internally-focused activism is central to Esther’s later choices as well. On the third day of her fast, Esther enters King Ahashveirosh’s inner chambers uninvited—an action punishable by death. Esther is given the opportunity to ask for whatever she wants from the king, “up to half the kingdom” (Esther 5:3). It is striking then, that instead of asking for a reversal of the decree against her people, Esther invites the king to gather with her and Haman. At the first feast, Esther is again offered “up to half the kingdom” (ibid. 5:6), and again invites the king and Haman to another feast. Esther works on getting buy-in from the king, opening his heart to her ask and not forcing his hand. Esther is working within a system: waiting for the short window of opportunity when she can access that which she needs. Only at the second feast, when asked a third time for what she wishes, does Esther point to Haman, centering the suffering of her people.

Her mode of action is characterized by attentiveness to instinct and to others, and by sensing and feeling the proper time for intervention. As opposed to externally-focused, linear activism, in which a goal is constantly pursued, Esther can be seen as working through a cycle, focused on the internal and the relational.

Conclusions

I wish to suggest this reading of the book of Esther as a key for facing a crisis. It is the story about a woman who didn’t plan to be a hero, who was just a ‘stay-at-home queen,’ yet found herself at the heart of the crisis. Moreover, the book of Esther gives us two heroes, a man and a woman. We have here two models of leadership in crisis, a male-coded one and a female-coded one. I believe the male-coded model is the one we most often turn to in Western society when facing a crisis. This is Mordekhai who is strong, who doesn’t submit to the villain, who takes to the streets and demands change. It is an important modality of being, but it is not the only one, and it is not enough. The book of Esther also gives us a second modality, a female-coded one, that is essential for working through crises.

Reading the story through the lens of internally-focused activism allows for us to shift the way we make meaning from Esther’s story. The book of Esther teaches us that there are different ways to act effectively in the world through crisis: Yes, doubting your need and ability to lead is acceptable. Yes, deciding to not jump right away and rather stop and gather your people is a mode of action. Yes, to empty yourself, literally through fast but also emotionally, or, in other words—to make space—is a mode of action. Yes, hosting meals is a mode of action, and manipulating a leader into a good direction is no less a mode of action than taking to the streets and speaking truth to power. And ye, making space for grief, the possibility of perishing, is important in leadership.

For the past 150 years, women have fought for—and in many cases have achieved—a voice in various societal sectors. But this process is still unfolding. The challenge isn’t just about amplifying women’s voices within existing structures but about integrating “feminine” or “internal” ways of leading—approaches rooted in relational thinking, cycles of retreat and return, and an ability to hold complexity without rushing to impose order. How do we center these ways of leading in times of crisis,alongside ‘Mordekhai’ struggle or resistance? What would it look like to bring these tools into the environmental crisis? Into the Israeli/Palestinian or Israeli/Diasporic Jewish crisis? There is no perfect model here. This is not a call for soft, easily palatable compassion, nor a rejection of external power. It is an invitation to expand our toolkit for survival and leadership in times that refuse to make sense.

Making choices in the face of a crisis is inevitable. Reading into our ancient stories of crisis gives us multiple ways of interpreting reality and, in them, the flexibility to choose rather than repeat the same default models. Demonstrating, demanding, and being strong, can only take us so far. We urgently need other forms of leadership as well. We need leaders who invite others in, with an awareness of timing, uncertainty, and the hidden. Leaders who are willing to work in the shadows, to cry, to pray. Leaders who in the face of a crisis might, counterintuitively, retreat or slow down.

But leadership is not just a matter for leaders with a big “L,” the prime ministers and presidents. It is also the way we conduct ourselves and the way we envision those fitting to lead us. Norms and practices never exist in a vacuum; they are strongly impacted by, and embedded in, the stories we tell as a society. In this essay, I interpret a story that informs these practices and norms, and outline how this story reflects on our ideas about normative response to crises today. Stories are the fabric within which culture is created; they are also the way every individual can understand more deeply their own psyche.[9] In this way, stories conserve symbols that help us better understand ourselves and the world. These two different forms of understanding, the internal and the external, complement each other: in the face of crises, when everything that made sense seems to disappear, we are asked to recreate meaning—to tell our story, and Esther is there to help us do exactly that.

[1] Special thanks to Noa Albaum for her thoughtful feedback on an earlier draft, and to the “Vatichtov” fellowship that supported the process of writing this piece.

[2] All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, eds. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katherine K. Wilkinson (One World, 2020).

[3] Throughout this article, when I use the terms “feminine” and “masculine” or “female-coded” and “male-coded,” I do not mean to say that feminine characteristics are essential to women only or vice versa; to the contrary. Every person has a feminine and masculine side, yet our society is often biased towards male-coded ways of interpreting reality and dealing with crises.

[4] All Tanakh translations are from JPS 1985, with minor modifications.

[5] Only later in the chapter, when Esther comes to the king, is her father’s name mentioned.

[6] The lesson plan is available here.

[7] The video is available on the 929 Project’s YouTube channel.

[8] Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, “Selfishness and Leadership in the Persona of Esther” [Heb.], available on the Yeshivat Har Etzion website (Mar. 14, 1989).

[9] See Haviva Pedaya, Kabbalah and Psychoanalysis: An Inner Journey Following Jewish Mysticism [Heb.], (Yediot, 2015), chapter 8.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.