Ari Lamm

“It was just me and this other guy in class,” explained a family friend, winking. “You know what I’m talking about.”

I did. Professor Feldman never had many students in his classes. At the time I heard this story I was taking Professor Feldman with four other students. An unheard of number as far as these things went.

“So one day the other guy calls in sick,” he continued, “and it’s just me and Louis Feldman in class. Everything was going great, but then about an hour in I had to go to the bathroom, so I told him I was so sorry I’d be right back. He told me: no problem, he would wait for me. So I went to the bathroom, came back, and we finished the lesson. Later that week the other guy and I are in class and out of nowhere Professor Feldman hands out an exam. Obviously we weren’t prepared. We asked him if this had been on the syllabus. He told us it hadn’t but he had mentioned in class several times that it was coming up. I told him I never remembered him saying anything about it. So Louis Feldman turns to me, looks me dead in the eye, smiles, and says: ‘Well, you wouldn’t. You were in the bathroom at the time.’”

A Harvard-trained classicist, Professor Louis H. Feldman arrived at Yeshiva University in 1956 as an assistant professor. Even typing those words feels to me like typing the beginning of Paul Bunyan’s biography. Professor Feldman—or, as many of his students knew him, “Louis” (pronounced like the Richard Berry song)—was a living legend. His tall, black yarmulke barely reaching the top of my shoulders, he was the smallest giant I ever met.

Looking back in the wake of his passing yesterday, the truth is that Professor Feldman’s career could easily have become one, macrocosmic lecture to an empty classroom. For a lesser scholar it probably would have. Professor Feldman’s expertise lay in the Jewish contributors to classical literature—especially the first-century, Jewish historian Josephus. For a field like Classics that in a broader sense boasts Homer, Herodotus and Plato, how much attention could be spared for Josephus? The answer, at least in the United States, is that to a large extent it was the sheer weight of Louis Feldman’s thorough brilliance that kept Josephus on the map.

***

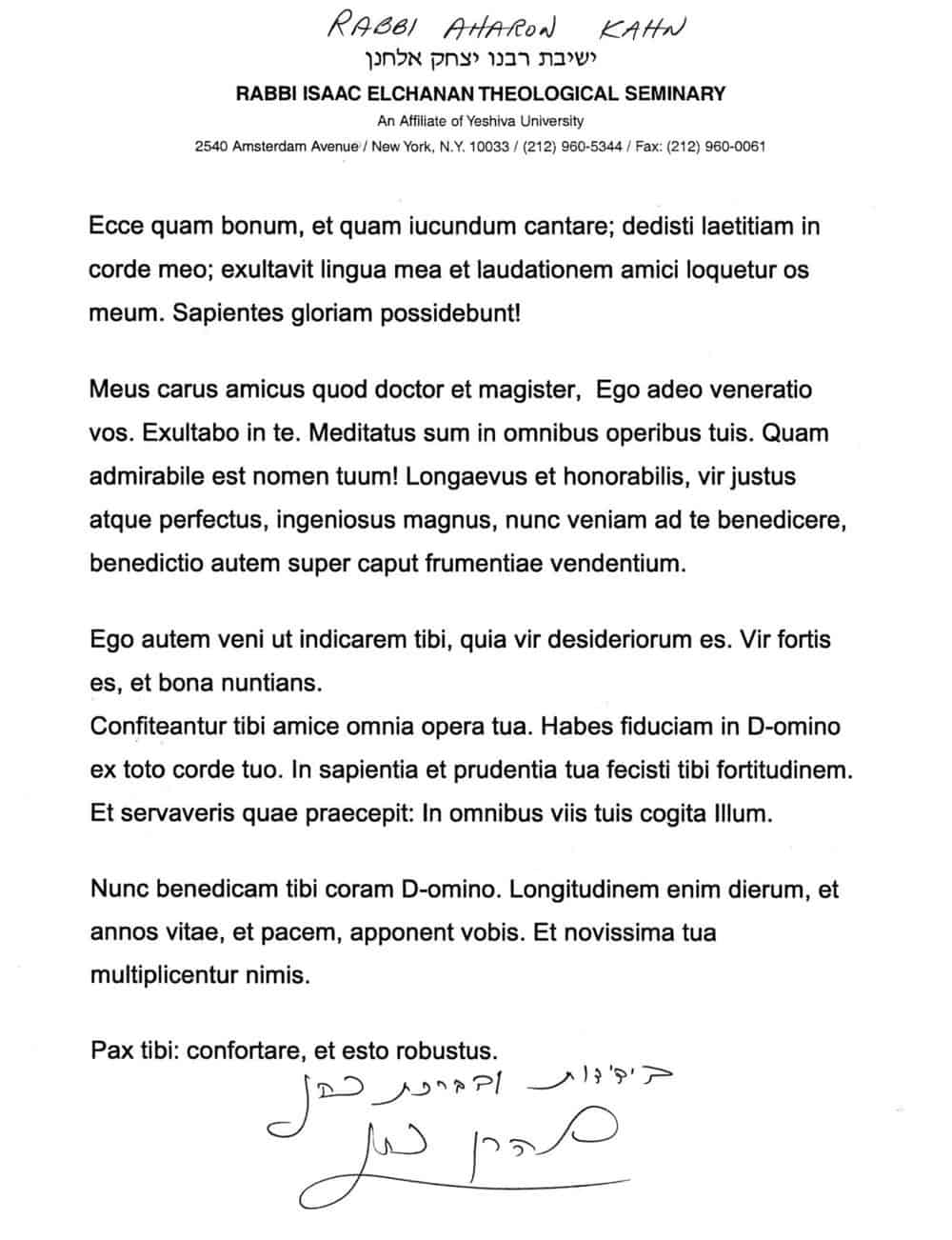

Letter from Rabbi Aharon Kahn in “Aere Perennius” (“More Lasting Than Bronze”): Letters in Celebration of Professor Louis H. Feldman’s Eightieth Birthday and Fifty Years at Yeshiva. Credit: Menachem Butler.

Letter from Rabbi Aharon Kahn in “Aere Perennius” (“More Lasting Than Bronze”): Letters in Celebration of Professor Louis H. Feldman’s Eightieth Birthday and Fifty Years at Yeshiva. Credit: Menachem Butler.

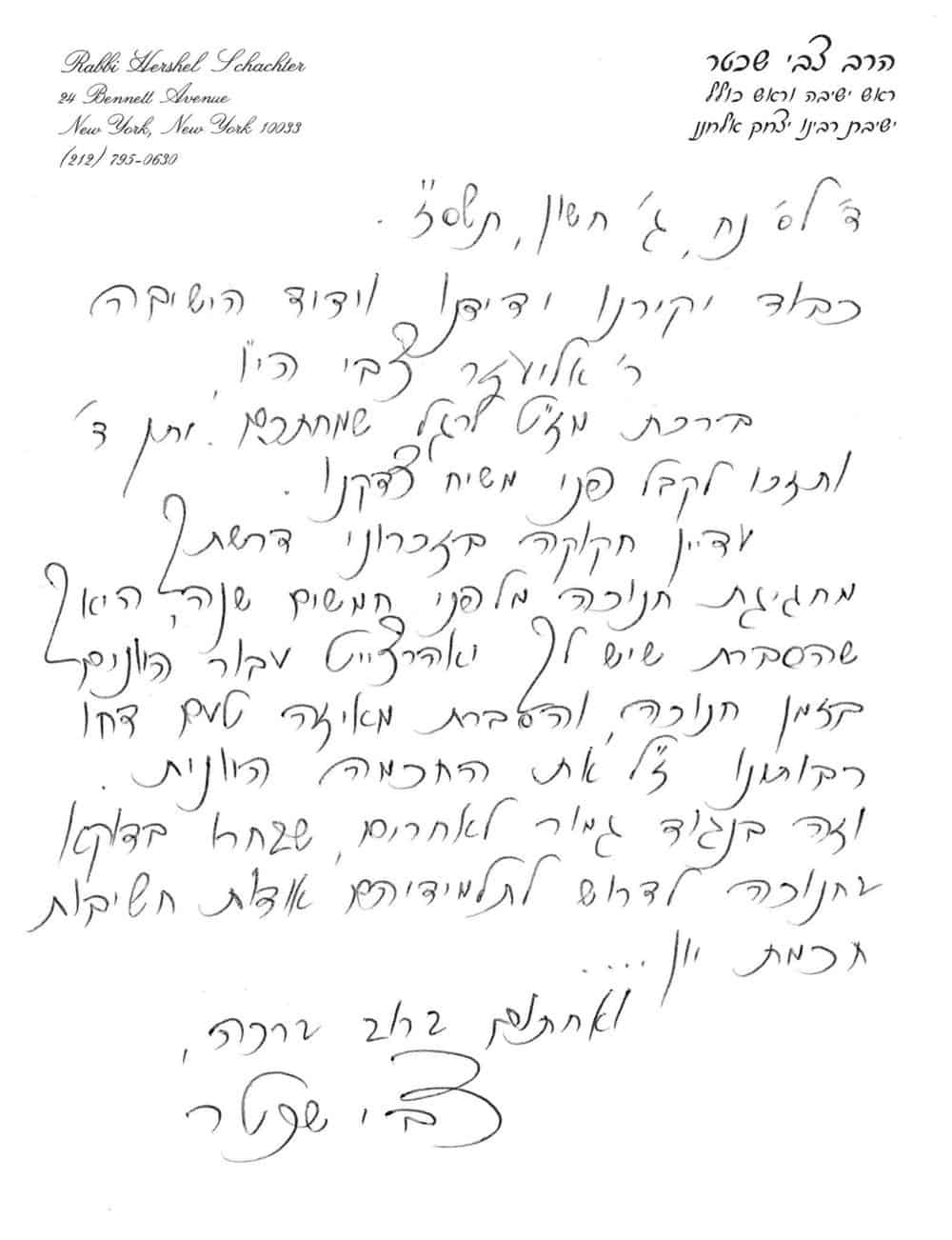

In 2006, one of Professor Feldman’s students—my dear friend and havruta, Menachem Butler—presented him with a volume, in honor of his eightieth birthday, called “Aere Perennius” (“More Lasting Than Bronze”): Letters in Celebration of Professor Louis H. Feldman’s Eightieth Birthday and Fifty Years at Yeshiva. This volume contained letters of tribute from several decades worth of Professor Feldman’s disciples. Among them were testimonials from Yeshiva University roshei yeshivah, Rabbi Aharon Kahn and Rabbi Hershel Schachter. Rabbi Kahn, in perhaps the most touching moment in the volume, composed his letter in Latin. After referencing several scriptural verses, including from Psalm 4 and Proverbs 3, Rabbi Kahn dedicates his letter to his dear friend and teacher for whom he has such veneration. Rabbi Schachter, for his part, recalled with fondness Professor Feldman’s “Yahrzeit shi’ur for the Greeks,” given around Chanukkah time.

Letter from Rabbi Hershel Schachter in “Aere Perennius” (“More Lasting Than Bronze”): Letters in Celebration of Professor Louis H. Feldman’s Eightieth Birthday and Fifty Years at Yeshiva. Credit: Menachem Butler.

Letter from Rabbi Hershel Schachter in “Aere Perennius” (“More Lasting Than Bronze”): Letters in Celebration of Professor Louis H. Feldman’s Eightieth Birthday and Fifty Years at Yeshiva. Credit: Menachem Butler.

That Professor Feldman’s work so touched not only academics but Jewish religious leaders of the first rank is a fitting tribute to his scholarship. After all, aside from his important translational and editorial work, one of Professor Feldman’s major contributions to our understanding of ancient Jewish writers like Josephus and Philo was in mining their work specifically for their Jewish concerns (whatever that might mean), rather than merely for historical information relevant to the eventual rise of Christianity. That is, he saw these writers first and foremost as Jews, interested in the traditional heritage of their people, namely, the Hebrew scriptures. Professor Feldman therefore became one of the best known practitioners in the “Josephus’ Portrait Of …” or “Philo’s Interpretation Of …” genre. In these articles he tried to tease out the particular manner in which these ancient Jews, writing in Greek, interpreted Biblical narratives. Most importantly, his stunning, multilingual erudition allowed him to put these interpretations in conversation not only with other Greek-writing Jewish authors, but also works of midrash and targum. Professor Feldman authored dozens of such articles—from Philo’s version of the Akedah, to Josephus’ portrait of Joshua. In so doing, he helped restore an appreciation for the dynamism of Jewish scriptural interpretation to its rightful place near the center of ancient Jewish historical study. Louis Feldman was convinced that ancient Jewish history was not just the intellectual equivalent of a museum where visitors might come and marvel at the relics of a bygone era; it was not just another interesting subject; it was instead a field of immanent importance for the living, breathing Jewish community of our time. As he showed better and more often than anyone, the objects of his study endeavored to understand the Torah just as do Jews today. No wonder he attracted the admiration even of contemporary Jewish spiritual leaders.

***

Professor Louis H. Feldman and the author.

Professor Louis H. Feldman and the author.

The three of us entered Professor Feldman’s office bearing gifts. Actually one gift in particular: a black and white cake from Butterflake Bakeshop. It was Louis Feldman’s eighty-third birthday, and we wanted to celebrate with our beloved teacher. So we placed the cake upon his article-strewn desk, and began to sing Happy Birthday. As we finished, we heard that warm, raspy laugh that never strayed far from Professor Feldman’s throat.

“Do you know the only person in our tradition ever to celebrate a birthday?” he asked, his eyes twinkling. “Pharaoh!”

No one could make a birthday speech like Louis Feldman.

But in this case beneath the surface of Professor Feldman’s humor ran one particularly strong intellectual current.

Professor Feldman’s most provocative work dealt with the interplay between Jewish and Greco-Roman culture, culminating in his 1993 book, Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World. Professor Feldman argued for the relatively minor impact of Greek culture on ancient Judaism in the Land of Israel. Moreover, in a related series of studies—some contained in that very work—he made the case for a robust Jewish spirit of proselytism through much of antiquity. This quest by Jews in antiquity for adherents found its complement in the range of people who “sympathized” with Judaism, or in some fashion became attracted to Jewish practice. Professor Feldman also sought to make the case that for all the revulsion some Greco-Roman authors appear to have felt for the Jews, some others maintained considerable admiration for Judaism, with its antiquity and deeply traditional codes of conduct.

Reviewers both critical of his work on these issues, and sympathetic to it, observed that Professor Feldman aimed at, among other things, countering the lachrymose view of Jewish history. The lachrymose (meaning “tearful”) view of Jewish history is one that sees the story of the Jewish people defined by a continuous series of tragedies. Professor Feldman, by contrast, was convinced that Jewish history was, as well, punctuated by moments of great joy, vigor and success, part of the Greco-Roman era being one such. The flip side of this conviction was an abiding sense that the wellsprings of Jewish religion and culture rand deep enough that even a sophisticated Greco-Roman cultural milieu could not hope to dislodge them from the heart of the Jewish people. Jewish history is defined by its vitality just as much as by sadness, and this is precisely because Judaism is itself full of vitality.

In the end, argued Louis Feldman, Judaism didn’t need the penetrating influence of Greek culture any more than it needs Pharaoh’s birthday parties.

***

“Caesar’s last words certainly weren’t ‘et tu Brute,’” exclaimed Professor Feldman one day in class.

How could he know that, we inquired.

“Well obviously,” he replied with that sly, playful smile of his, “he never would’ve died speaking Latin like an amaretz. He would have spoken Greek!”

Professor Feldman possessed an indefatigable sense of humor that only sharpened with age. In my notes from January 27th, 2009, I wrote down the following:

“The Romans had an inferiority complex for no other reason than that they were inferior, at least in terms of genealogy.” – Professor Feldman, on [the Roman historian] Livy’s attempt to supply the Romans with a somewhat more distinguished past than they probably deserved.

There was no element of classical history that the great Louis Feldman could not make come alive with his flash-quick wit. But lest the reader think that Professor Feldman was merely a comedian, his humor always accompanied a generosity of spirit towards all who encountered him. In particular I’ll never forget his insistence at the end of each lesson that, in advance of the next one, we should all email him any questions we had about any of the course readings, past or future. And any time I would send him a question—even one or two lines—he would invariably write back with at least a page and a half worth of notes. In response to one question I sent him about Virgil, he invited me to his home to have a look in his library while we hunted down the answer together. I know I was far from the only student granted this privilege. His caring, especially for his students, knew no bounds.

And in the final sum of things, that is Professor Feldman’s true legacy.

However small his classes may have been, his students have nonetheless gone on to exceedingly prominent positions in academia and even the rabbinate. And to a person, they each speak of Louis Feldman with that same warm glow in their eyes. The mere mention of his name is enough to evoke memories not only of overwhelming expertise, but also of great magnanimity and concern. Indeed, as a student not only of Professor Feldman, but of many of his students as well, I can report with confidence that Professor Feldman’s extraordinary kindness is as much a part of his legacy as his scholarship.

May his memory be a blessing.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.