Gabriel Slamovits

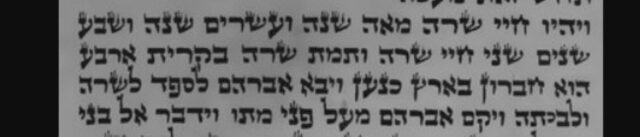

The final word of the second verse in this week’s parashah is written in the Torah with a minuscule letter: “And Sarah died in Kiryat Arba, that is Hevron in the Land of Canaan, and Abraham came to eulogize [or mourn] Sarah and to weep for her” (Genesis 23:2). Kaf, the fourth letter of the word וְלִבְכֹּתָֽהּ, “and to weep for her,” is writ small.

There is a classic teaching of the Ba’al Shem Tov, the eighteenth-century founder of Hasidic Judaism, that each of us is like a letter in the Torah, or as Rabbi Jonathan Sacks put it in his book of that name, that we are each “a letter in the scroll.” In the context of Genesis, the universal story of creation, one can think of Adam and Eve as prototypical humans represented by the letters of the alphabet written in the Torah scroll. Most letters are neither majuscule nor miniscule, but are regular-sized. There are times, however, when we humans feel taller, just as there are moments when we feel smaller. Those moments can be represented by the larger or smaller letters in the Torah. Here, Abraham felt diminished by the pain of losing his wife, a pain that is represented by the small kaf in the word which tells us that he wept.

There is, however, a second way of looking at the small kaf based on the comment of Philo of Alexandria, who, in his Quaestiones on Genesis, notes that Abraham only “came to eulogize Sarah and to weep for her,” but that Scripture does not report the actual eulogizing and weeping that Abraham did.[1] Perhaps, then, the small kaf signifies not only that Abraham was diminished, but that his eulogizing and weeping was somewhat diminished.

In his masterful collection of essays on mourning, Out of the Whirlwind, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik taught of the Talmudic distinction between aveilut yeshanah, “historic mourning” for a past tragedy, and aveilut hadashah, “individual mourning” spurred by grief from a recent loss.[2]

Jews have a unique historical consciousness; we have the practice of not just remembering our holidays and tragic days, but of reliving them. On Sukkot, we sit in booths, just as our ancestors did in the desert. On Passover, we reenact the Exodus from Egypt, eating matzah and bitter herbs. And on Tishah be-Av, we mourn for the loss of the Temple, almost as though it had been destroyed days ago and not thousands of years ago. That grief seems to be never-ending. One of Rav Soloveitchik’s students summarized how this “historic mourning” differs from individual grief:

The concept of continued, unending mourning is a special, unique aspect of avelut yeshanah, mourning for a tragedy that occurred long ago, as opposed to avelut hadashah, mourning for the recent bereavement. In the case of avelut hadashah, there are limits, and Maimonides says[3] that one who mourns “too much” is acting foolishly.[4]

Judaism teaches that there should be limits to the grief caused by a recent bereavement. In this context, Philo writes that to over-grieve is, as Rabbi Samuel Belkin summarized it, “a sign of selfishness.”[5]

The small kaf in וְלִבְכֹּתָהּ, then, teaches us two seemingly paradoxical messages: that Abraham was diminished by grief, but also that his grief, his “weeping,” had limits.

I write these words about grief only a few days after the passing of our teacher, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l. Three years ago, he visited my community, The Downtown Minyan in Lower Manhattan, to join us in prayer and in learning Torah. On that Shabbat, he reflected on a notion he has also written about: that at the time of Sarah’s death, God’s promises to Abraham had largely not been fulfilled. His written words are well worth quoting in full:

Seven times he [Abraham] had been promised the land of Canaan, yet when Sarah died he owned not one square-inch of it, not even a place in which to bury his wife. God had promised him many children, a great nation, many nations, as many as the grains of sand in the sea shore and the stars in the sky. Yet he had only one son of the covenant, Isaac, whom he had almost lost, and who was still unmarried at the age of thirty-seven. Abraham had every reason to sit and grieve.

Yet he did not. In one of the most extraordinary sequences of words in the Torah, his grief is described in a mere five Hebrew words: in English, “Abraham came to mourn for Sarah and to weep for her.” Then immediately we read, “And Abraham rose from his grief.” From then on, he engaged in a flurry of activity with two aims in mind: first to buy a plot of land in which to bury Sarah, second to find a wife for his son. Note that these correspond precisely to the two Divine blessings: of land and descendants. Abraham did not wait for God to act. He understood one of the profoundest truths of Judaism: that God is waiting for us to act.

How did Abraham overcome the trauma and the grief? How do you survive almost losing your child and actually losing your life-partner and still have the energy to keep going? What gave Abraham his resilience, his ability to survive, his spirit intact?[6]

The answer, Rabbi Sacks said, is one that he learned from Holocaust survivors, who “did not talk about the past, even to their marriage partners, even to their children. Instead they set about creating a new life in a new land.” The lesson he learned was that “first you have to build a future. Only then can you mourn the past.” He continued:

Abraham heard the future calling to him. Sarah had died. Isaac was unmarried. Abraham had neither land nor grandchildren. He did not cry out, in anger or anguish, to God. Instead, he heard the still, small voice saying: The next step depends on you. You must create a future that I will fill with My spirit. That is how Abraham survived the shock and grief. God forbid that we experience any of this, but if we do, this is how to survive.[7]

The small kaf reminds us that though we may be diminished by grief, we cannot let it overtake us; we must build toward a future. Rabbi Sacks frequently reminded us of the value that Jews place on education, our investment in the future. In his Maiden Speech at the House of Lords, he said:

In ancient times the Egyptians built pyramids, the Greeks built temples, the Romans built amphitheatres. Jews built schools. And because of that, alone among ancient civilizations, Judaism survived.[8]

Our emphasis on education is precisely what allows us to celebrate the holidays in such a way that we actually relive them, reexperiencing the Exodus from Egypt at the Seder and mourning for the Temple on Tishah be-Av. We are able to mourn our collective past because we build the future, and we are only able to build the future by limiting the grief for our recent losses. Aveilut yeshanah is only possible when we limit aveilut hadashah. Abraham showed us the way forward; his small kaf is symbolic of that. And when we recognize that, then we, too, will move forward with unceasing faith in our capacity to build the future.[9]

[1] Philo, Quaestiones et Solutiones in Genesin et Exodum, Genesis 23: 2-3.

[2] See Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “Avelut Yeshanah and Avelut Chadashah: Historical and Individual Mourning,” VBM (2004); Yevamot 43b.

[3] Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Avel 13:11.

[4] “Commentary on Kina 45 (“Lament, Zion”),” in Koren Kinot Mesorat HaRav, ed. Simon Posner (Koren, 2010), 614-615.

[5] Rabbi Dr. Samuel Belkin, In His Image: The Jewish Philosophy of Man as Expressed in Rabbinic Tradition, (New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1960), 25.

[6] Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, “Faith in the Future,” Covenant & Conversation, Parshat Chayei Sarah 5776 (November 12, 2015).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, “Maiden Speech – House of Lords,” (November 26, 2009).

[9] “Faith in the Future” is a reference to the title of Rabbi Sacks’s 2015 devar Torah on this parashah cited above.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.