Tikvah Wiener

EDITORS NOTE: This article is part two of our mini-series on new directions in Jewish Education. Part one is available here.

This past year my faculty and I opened The Idea School in Tenafly, NJ, the first Jewish interdisciplinary, project-based learning (PBL) high school in America. The school is the realization of about a decade of study and practice in progressive education and what it means to bring it to a Jewish setting. While the educational model for The Idea School is the High Tech public charter schools in San Diego, CA–a network of K-12 PBL schools–our school is the first to fully integrate Jewish and General Studies, and to do so using project-based learning.

In PBL, the learning is driven by a question that’s enticing to students, so that they want to explore further. Students then probe (often traditional) content through the lens of the question, using it to make meaning of the curricula. They have to create artworks, products, or events from their learning, often working collaboratively to do so; and they also get and give feedback, revise their work, and present it publicly to a wide audience. This kind of process-oriented learning becomes personally meaningful to the student, and should be connected to the real world in relevant and authentic ways.

PBL falls under the category of progressive, constructivist education, which psychologist Jerome Bruner describes as an often hands-on type of learning that compels and empowers students to construct meaning out of what they study. It’s noteworthy that in progressive models of education constructing something out of one’s learning does actually help in the process of constructing meaning, but the latter is what Bruner is more concerned with. He writes in one of his seminal works, Toward a Theory of Instruction:

To instruct someone… is not a matter of getting him to commit results to mind. Rather, it is to teach him to participate in the process that makes possible the establishment of knowledge. We teach a subject not to produce little living libraries on that subject, but rather to get a student to think mathematically for himself, to consider matters as an historian does, to take part in the process of knowledge-getting. Knowing is a process not a product. (1966: 72)

On the other hand, Ron Berger, one of the most well-known and admired practitioners of PBL today, places great emphasis on the actual construction of products in the course of a PBL unit, extolling the benefits to students of creating beautiful work: they learn the value of craftsmanship and feel a sense of accomplishment over what they have made. Berger emphasizes the deep, rigorous learning that takes place as a result of PBL, and in this way aligns with Bruner but without specifically noting that the effect of deep learning is a student’s arriving at meaning through the learning process.

A study of PBL necessarily engenders familiarity with other constructivist pedagogies, one of the more famous being experiential learning, which many educators often tend to think of as camp-like, immersive experiences in which learning occurs. Another important constructivist pedagogy is inquiry-based learning (IBL), which possesses the same elements as PBL but is wholly driven by student interests. In their provocative work, Teaching as a Subversive Activity, Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner ask why schools should even have curriculum? Teachers should simply build coursework around questions students generate. This approach has been adopted by Democratic Schools (of which there are quite a few in Israel) that don’t require students to take any particular courses, and instead allow them to study any subjects and engage in any activities in which they’re interested.[1]

—

The specific constructivist pedagogies that underpin The Idea School are PBL and IBL, and I studied these closely when I visited and trained at the High Tech schools. The schools challenged me to rethink my approach to education, and particularly to consider how a constructivist model might be applied to Jewish education. One of the first things that caught my attention at the schools were the cross-disciplinary projects: the schools take two main disciplines and yoke them together in thought-provoking, often whimsical ways.

For example, a physics and art teacher collaborated to create the Staircase to Nowhere project, in which students explored the physics of building, and then built their own unique staircases that led nowhere. A collaboration between the same art teacher and a calculus teacher another year led to Calculicious, an artistic math book. Writing was a central piece of the latter project as well, as students had to record their progress on a class blog and explain their process, including decision-making and trouble-shooting, in writing pieces.

One project I became enamored of was a service learning one that inaugurated freshmen one year at High Tech High. Ninth graders studied ancient philosophers’ views on philanthropy, interviewed local philanthropists–including a major donor to the school–and completed a service learning project which they photo-journaled and hung on the school walls. What better way to build a sense of community among new students in the school than with such an opening unit? And how easy it was to imagine building out the project to include Jewish texts on why we should engage in acts of hesed and what are the obligations in distributing charity.

The philanthropy project caught my interest because it spoke to the whole person in ways the Staircase to Nowhere and Calculicious might not. While those projects were fun and creative, and designed to get even the most reluctant math and physics students excited about what they were learning, the service learning project had even deeper aims: it was interested in the social and emotional well-being of the child, initiating her into the school culture, and enabling her to discover what it means to care about society. The learning was horizontal, laying out the landscape on which students were situated.

But it went even deeper: by having students study what ancient philosophers had to say about philanthropy, the school took students in a vertical direction as well, having them look back into the past from which our current Western culture has sprung (and marrying the project to state curriculum standards at the same time). The photo-journalism component of the project capped it well by literally having students place themselves in the picture, on the walls of their new school, and in the continuum of the historical timeline of their community and the world.

This project, so deliberately and intentionally designed to maximize impact on the student, school, community, and world, jumped off the walls at me. Its goals seemed perfectly aligned with ours as Jewish educators.

—

When The Idea School faculty and I began planning our PBL units, we decided that the aim of our first year-long curriculum, our ninth grade one, should not only be to acclimate students to high school, but to give them the independence, work habits, and ability to regulate their behavior that they need to succeed academically and in life. We also wanted students to develop civic responsibility and a refined ethical sense. In short, we were guided by a mishnah from Pirkei Avot (1:14) that found its way into our mission statement:

אִם אֵין אֲנִי לִי, מִי לִי. וּכְשֶׁאֲנִי לְעַצְמִי, מָה אֲנִי. וְאִם לֹא עַכְשָׁיו, אֵימָתַי

If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And if I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?

To me, this mishnah embodies what project-based learning is all about: first, it acknowledges that living has to start with the self–taking care of one’s own needs, and knowing and developing one’s self to the best of his abilities, so he can become actualized. Only then can one turn to the world and offer what he has developed–his unique gifts and talents. And this demand that self-improvement begin now enforces the notion for PBL educators that, as educator and philosopher John Dewey noted, education isn’t preparation for life; it is life itself.

That education should have immediate purpose for students is something I heard often at the High Tech schools. Their founder and CEO Larry Rosenstock tells visiting educators that if students ask their teachers why they’re studying a specific topic or subject, he doesn’t want the answer to be, “You’ll know when you get to college” or “This will be helpful later in life.” Learning should matter to the student now, should be relevant to the student’s world today. When you walk through the halls and classrooms of the school, you constantly see artifacts of learning reflecting that philosophy: murals in the artistic style of an Hispanic artist, painted by two seniors who are Hispanic; digital artwork about identity completed by middle schoolers who reflected on their adolescence; math projects that had students using data to understand themselves and have empathy for others; a DNA bar-coding project that helped trackers in Africa catch poachers.

Of course, this focus on personal relevance and purpose in school must be balanced with an emphasis on preparing students for college. While the High Tech schools don’t spend class time on test prep for the California state exams, the students score about 10% higher than the state average; and the schools do have a strong SAT and ACT prep program, a testament to the fact that Rosenstock believes “we prepare our kids for the tests that matter, and the SATs and ACTs matter. . . . Do I think it’s a good idea for a student to do a math problem in 3 ½ seconds? No, but tough noogies on us. Unfortunately, a three-hour exam is equal to three years of work [in high school].”

Rosenstock also believes that schooling is not an “either-or” proposition; it’s “both-and.” Schools can be both places where learning matters to the student personally and in the real world and also places that prepare them for college. In fact, many of the students at the High Tech schools are the first in their families to be college-bound, and yet the schools have a 99% acceptance rate into college, with students attending anywhere from Ivy League schools to the California state schools and universities to which many of them apply. Luna Rey, a student we befriended, recently graduated Columbia University with a degree in education and wrote about how her project-based learning education helped her thrive in college.

—

What I hear often from Jewish educators about PBL is a concern that the pedagogy doesn’t cover enough content, and a main purpose of Jewish schools is to provide students with broad literacy in religious texts. This is something we very much consider at The Idea School, and we’re trying to strike a balance: after all, we want our students Jewishly literate as well as ready for a gap year in Israel should they decide on that path for themselves.

But if we’re to benefit from a constructivist approach, and contemplate what each student needs to develop herself, then we arrive at a place where we’re drawing deeply from Jewish knowledge to help students grapple with who they are, who they want to become, and what purpose they will serve in the world.

Thus, when we introduced freshmen not only to the school but to project-based learning, our driving question was, How do we cultivate good habits? Like High Tech High’s service learning project, this PBL unit impacted students’ emotional well-being by taking them through a journey of self-exploration and the world today. It also empowered them to explore the past, which of course included our own religious heritage. In Humanities, students studied ten habits of ancient civilizations, while in Beit Midrash [what we call our major Judaic Studies block of the day], they examined Sefer Bamidbar through the lens of those same habits.

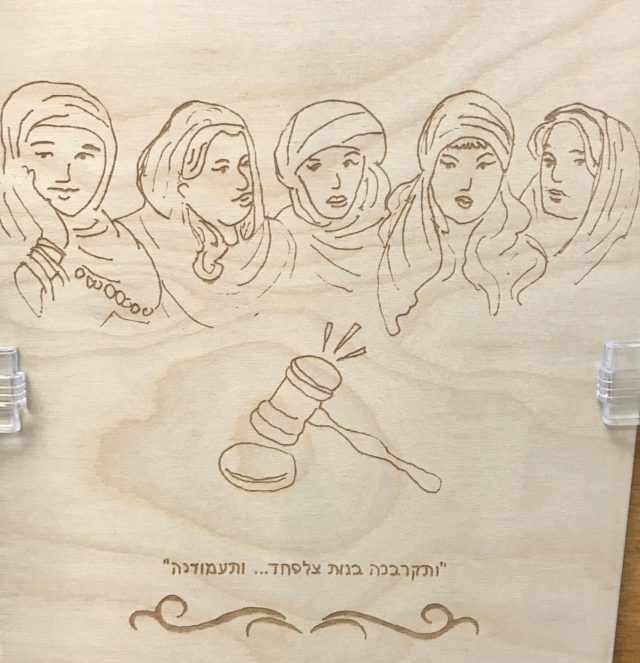

Students, for example, discussed how the manna related to ancient ways to store surplus food, connecting the topic to ways we currently distribute surplus food to the needy; or contemplated gender inequity and the daughters of Zelophehad, conveying how gender today is still such a hotly contested topic. As one of the final Beit Midrash deliverables of the unit, each student drew an image that we transferred onto a laser-cut wooden panel. The image depicted a habit of ancient civilization that the Israelites experienced in the wilderness, and that we can still see functioning in the world today.

Like the High Tech students, ours not only learned texts of the past, but applied them to today’s world, used them to create artwork, and wrote about their experience doing so. The students’ wooden panels now adorn the walls of our Beit Midrash. Their learning is a living, enduring thing. (Click here to view a panel on B’not Zelophehad, which shows the women in individualized ways, a verse about their standing up for themselves, and a modern-day gavel to reflect the fact that each Jewish woman today should find her voice in order to advocate for herself).

While the first unit of the year was focused on building a sense of self–אִם אֵין אֲנִי לִי, מִי לִי– the second was on taking the self and turning it outward–וּכְשֶׁאֲנִי לְעַצְמִי, מָה אֲנִי. The second unit asked students to consider what makes a good citizen, what levers they use to make ethical decisions, and how the Talmud informs their sense of Jewish citizenship. They debated personal morality versus civic responsibility, and discussed a wide range of ethical dilemmas in medicine, business, and general life. They were asked to share their learning with the staff of the Kaplen JCC on the Palisades, where our school is located; and they had to prepare mishnayot from Pirkei Avot, which we learned throughout the unit before prayer each morning. The final large deliverables were a Rube Goldberg machine that reflected Talmudic and ethical thinking, and a mock trial in which students tried the Greek heroine Antigone for disobeying a law of Thebes.

—

Using a constructivist approach to learning, where meaning-making is the foundation on which we build curricula, we empower students to find their own significance in Jewish texts and their heritage.

Another example: students explored heroes and villains in Megillat Esther, at the beginning of our third PBL unit of the year, on storytelling. After identifying who the heroes and villains were in the Megillah’s story, students then had to research a hero or villain in the Torah and find a midrash that told that character’s story in an entirely different way. The Beit Midrash was humming during that time, as students chose characters that enticed them to take another look, whether that character was the snake in the Eden story, Esau, or even Moses. The room was alive with excitement and discovery as students researched their characters and told their stories from another view. The students were interested in their learning because they had chosen what to explore, and by seeing that their tradition could understand characters from multiple angles, they learned that Judaism is flexible enough to accept a multitude of contrasting perspectives.

Our students have also become unafraid of the research process because of the type of learning they’re engaged in. One of the first skills they developed in the Beit Midrash was the ability to use Sefaria as a research and source-sheet building tool. During the first trimester, students made their own source sheets on a habit of civilization they explored in Sefer Bamidbar. During the second trimester, they worked in pairs to create source sheets for the shiur they gave to JCC staff. Now, when a student is asked to come up with a text to deepen their Jewish learning, you can find them searching Sefaria for commentaries and ideas.

A second Judaic Studies block of time is devoted to our Inquiry Beit Midrash, developed as part of JEIC’s HaKaveret Design program and employing inquiry-based learning in a Jewish context. The Inquiry Beit Midrash is a place where students learn to ask questions that interest them about their Judaism; follow a line of inquiry into Jewish texts that answer their questions; and create products of learning from what they’ve studied. Students are exploring Mashiah, natural morality, languages, holidays, conversion, and other topics they find important in Judaism. They work in small groups under a teacher-mentor’s guidance and come up with artifacts of learning they want to create.

As you can tell, a big difference between a constructivist approach and more traditional schooling is that progressive educators transfer agency from themselves to the students, and this can feel scary to teachers because they might feel out of control in their classrooms. (There are plenty of norms and structures in progressive education; they just differ from traditional ones.) Jewish educators also might believe that they’re somehow altering the mesorah, the chain of tradition that links us to our ancestors. But what I’ve seen in The Idea School Beit Midrash and Inquiry Beit Midrash is that our students–and teachers–are deeply involved in what anyone in any Beit Midrash is doing–engaging in learning le-shem shamayim and, by doing so, bringing themselves closer to God and bringing God more closely into the world.

—

In order to advance our educational goals, The Idea School has made decisions about curriculum that not every school is prepared to make: we don’t divide our Judaic Studies time into Humash/Torah, Navi/Prophets, and Talmud classes. Instead, a two-hour Beit Midrash block of time in the morning focuses on one major corpus of Jewish texts, either Tanakh or Talmud. We made those decisions based on research into deep learning and the practice at the High Tech schools of minimizing the number of classes students take each day so they can fully immerse themselves in their courses and not be mentally fatigued by constant code switching. A dual curriculum already makes a heavy cognitive demand on our students; we want to make sure they find their learning refreshing and inspiring, not draining and enervating. This is especially important for their Judaic Studies classes, where our goal is to ignite a love of Torah and Jewish living.

And that’s why we added the Inquiry Beit Midrash twice a week in the afternoon, instead of another block of time wholly dedicated to one set of Jewish texts. We wanted to give students the chance to explore their religion in ways that were uniquely personal. As we grow the school, we’ll also offer interested students the chance to learn Talmud or Tanakh bikiyut, at a fast pace that covers a lot of material. If we’re focused on the needs of each learner, then that style and type of learning also becomes an integral part of our program.

There’s much to master and ponder about progressive education and how it might be applied to Jewish settings, and there are lots of Jewish educators today doing just that: melding STEAM with Jewish studies; using the arts in the Beit Midrash; adapting PBL online learning systems to Jewish project-based learning; integrating civics education with Jewish texts; and making visits (often with me!) to the High Tech schools. Not everyone need adopt constructivist education wholesale, but it’s certainly worth a look at some of the exciting opportunities it offers to inspire students in new ways, and to help them realize they have the power to make meaning of our rich and unique religion.

[1] Constructivist, progressive educators have been touting the benefits of meaning-making and hands-on learning for over a century (Maria Montessori, one of the movement’s more well-known figures, lived 1870-1952), but the pedagogies have taken some time to take hold successfully. The High Tech schools, which have existed for the past two decades and which now have a Graduate School of Education, are one of the movement’s current thought leaders, providing professional development and even a master’s degree. The Stanford Graduate School of Education has also become a mecca for progressive education. In fact, one of the school’s most prominent professors, Dr. Denise Pope, started the organization Challenge Success which, as its website says, pushes back on a society “that has become too focused on grades, test scores, and performance.” (Pope weighed in on the recent college admissions scandal in an article in the Wall Street Journal, “The Right Way to Choose a College.”)

Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, particularly Project Zero, is also contributing to the plethora of resources now available to progressive educators, and the Buck Institute of Education provides on-site PBL professional development and year-round PBL conferences.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.