Ezra W. Zuckerman Sivan

If there is a foundational idea for the high holiday season, it is surely the redemptive power of viduy or public confession. And if there is anyone in Jewish history who exemplifies this redemptive power, and how it may redress our pernicious tendency to cover up sins rather than confess them, it is King David.

Consider first the cover-up. Don Isaac Abarbanel (1437-1508) lists five “aspects” to David’s sinning in chapter 11 of II Samuel, consisting of an ‘original sin’ and those elicited by the ensuing cover-up:

- He had sexual relations with Bathsheba, a woman who was married to his stalwart officer Uriah the Hittite (II Samuel 11:2-4).

- After learning from Bathsheba she was pregnant, he tried to distort the ancestry of the child by luring Uriah into having a conjugal visit with Bathsheba (11:5-13).

- After failing in this first plan, he committed manslaughter by issuing orders to his general Joab that put Uriah’s life (and those of others) at unnecessary risk (11:14-25).

- David thereby caused Uriah—and others who fell that day—to suffer an undignified death.

- David took Bathsheba as a wife immediately after the mourning period, thus violating the Halacha mandating a three-month waiting period to clarify paternity (11:27).

Where is there a more dramatic illustration of how a cover-up tends to exacerbate a crime?

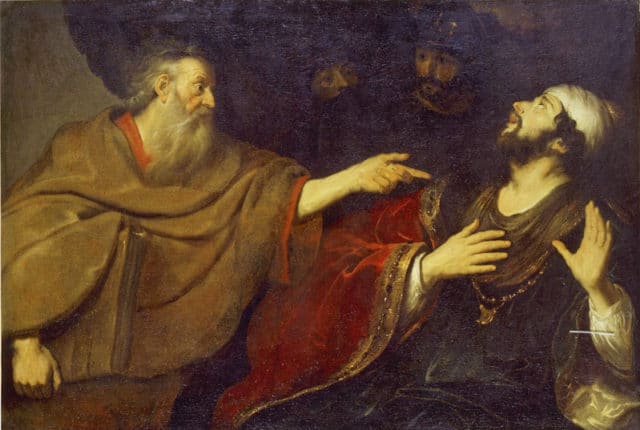

Yet if David’s response to sin is a paradigmatic cover-up, his response when confronted by his sin seems to be a paradigm for the redemptive power of confession. Unlike Saul who reacted to the prophet Samuel’s rebuke by blaming his failure on others (I Samuel 15:20-21),[1] David accepts full blame when he is confronted by the prophet Nathan. As recorded in II Samuel, David offers only a simple two-word response: “I have sinned to God” (12:13). And if this version of David’s confession is perfect in its simplicity, the version in Psalm 51 (“a psalm of David, when Nathan the Prophet came to him after he had come to Bathsheba” (51:1-2)) is perfect in its eloquence. In this moving prayer for “compassion and mercy” (51:3), David deploys the word het or “sin” seven times to refer to his actions, establishing it as a “guide word” for the poem. He also uses two synonyms for sin— pesha and avon—three times each, with the thirteen total references to sin likely alluding to the thirteen attributes of God’s mercy (Exodus 34:6-7).[2]

Strikingly, this confession seems effective. To be sure, David and Bathsheba’s newborn son is soon struck dead by a divine plague, and David’s family and monarchy suffer from unending turmoil and scandal in the ensuing years in accordance with Nathan’s curses (see 12:10-11). But David’s death sentence is commuted, and he and Bathsheba merit the birth of a second son, Solomon, who is beloved by God (12:24) and ultimately inherits the throne.

Yet to note that David’s confession had redemptive power is not to explain this power: Given the magnitude of David’s sins, could the mere uttering of words and prayers of repentance truly be sufficient to mitigate them?

One approach is to point to various technical legal considerations that mitigate David’s sins. An extreme position is reflected in the famous admonition of R. Shmuel Ben Nahmani in the name of R. Yonatan (Shabbat 56a): “Anyone who says that David sinned is but mistaken.”[3]

But such apologetics seem strained; and accordingly, this is hardly the consensus view.[4] Certainly Nathan the Prophet was unimpressed by any exculpatory points in David’s favor. As R. Yaakov Medan notes, Nathan’s rebuke is consistent with the general approach of “the prophets [of Israel who] were unimpressed with formal excuses for moral transgressions based on technical-legal considerations; and in their words of rebuke, the prophets ignored such considerations as if they were naught.”[5]

Thus let us follow Abarbanel in not “countermanding the simple truth” by “tolerating a lessening of David’s sin.”[6] At the same time, let us consider the possibility that we have yet to fully grasp the nature of David’s sin, and of the significance of his cover-up and confession.

Quite strikingly, the analysis in the next section indicates that the biblical text is hinting loudly that David’s sin has an important dimension below the surface. Furthermore, we will see that an appreciation for this dimension can resolve several outstanding puzzles in the story of David and Bathsheba. And we will also see that it carries three important lessons regarding the perniciousness of cover-up and the redemptive power of confession.

The Yibbum-Theme in David’s Sin

The heart of the suggested approach is an analysis of the many textual and thematic links between the story of David-Bathsheba in chapters 11-12 of II Samuel and the story of Judah and Tamar in chapter 38 of Genesis.

To recall, the story of Judah and Tamar culminates in the birth of Peretz, who was the ancestor of David’s forebear Boaz (Ruth 4:18-22). At the heart of the story is a struggle by Tamar to ensure that a man from Judah’s family perform yibbum or levirate marriage, the ancient rite (found also in other ancient/patriarchal cultures) by which a brother of a man who dies without children marries the childless widow and dedicates their child to his dead brother’s legacy. Judah’s second son Onan ostensibly accepts his responsibility as levir for his deceased brother Er, whom God had killed because he was evil (Genesis 38:7). But God kills Onan as well as punishment for refusing to “give seed to his brother (38:9)” by consummating the marriage. Then, with two sons mysteriously dying while married to Tamar, Judah delays having his third son Shelah be the levir. Tamar’s patience eventually wears thin and she takes initiative by seducing Judah in the guide of a (veiled) roadside prostitute. In this way, she induces him to perform the role of levir and inter alia to recognize his error.

At first glance, this story would seem to have little to do with the story of David and Bathsheba. But a review of the many links between the stories strongly suggests that we take a closer look:[7]

- Each story begins with a leader abandoning his brothers (see Genesis 38:1) or comrades (II Samuel 11:1).

- An announcement of an illicit pregnancy is pivotal to each story, with parallel statements of acknowledgement that appear nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible: harah anokhi (II Samuel 11:5) and anokhi harah (Genesis 38:25).

- In Genesis 38, the protagonist begins the story married to a woman named Bat Shua (38:12), who is Canaanite. In II Samuel 11, the protagonist ends the story married to a woman named Bat Sheva (Bathsheba) (referred to as Bat Shua by I Chronicles 3:5) who was married to a Hittite.

- The male protagonist’s lust is elicited by a woman who is dressed in an unconventional or provocative manner—uncovered in the case of Bathsheba and covered in the case of Tamar.

- This woman is observed in a scene associated with water (bathing in the case of Bathsheba, at springs in the case of Tamar).[8]

- In both stories, the woman is ironically referred to with the root for holy, kadosh, precisely to refer to preparations for the illicit relationship. In Tamar’s case, it is the word for cult prostitute (kedeishah; Genesis 38: 21-22). In Bathsheba’s case, it refers to her immersing herself after menstruating (ve-hi mitkadeshet mi-tumata ; II Samuel 11:4).

- There is unusually extensive use of agents throughout each story, perhaps suggesting that each story is in part about how a leader goes astray when he has others do his ‘dirty work’. In particular, there are five instances of shalah (“send”) in Genesis 38, and 15 instances in II Samuel 11-12), with the heaviest use pertaining to the procurement of the woman for the illicit liaison (David-Bathsheba) or to paying her (Judah-Tamar).

- In both stories, the cessation of mourning is prelude to sex. This happens twice for Bathsheba (II Samuel 11:27 and II Samuel 12:24), and once each for Judah (Genesis 38:12) and Tamar (38:14). In each case, the word vayenahem —“and he comforted” (II Samuel 12:24), or vayyinnahem — “and he was comforted” (Genesis 38:12), is the sign of movement from mourning to availability for the sexual encounter that leads to the birth of an heir.

- In both stories, a man (Onan, in Genesis 38; Uriah, in II Samuel 11) refuses the opportunity/mandate to have intercourse with his wife. In both cases, this failure leads to that man’s death due to the orders of a king (God, in Genesis 38; David in II Samuel 11).

- Each story involves a theme of bizayon or denigration/calumny. In Genesis 38, Judah is reluctant to give Tamar to his third son Shelah as a levir “lest we come to calumny”(pen nihyeh lavuz ; Genesis 38:23) and Nathan twice uses this terminology in describing David’s sin (“ekev ki bizitani” “madua bizita et devar Hashem”; II Samuel 12:9-10).

- The two stories contain the only two instances in the Hebrew Bible in which there is a transitive verb phrase in which (a) the object is artzah, to/towards the ground; (b) the subject is “and he”; and (c) the verb starts with the letter shin. In Samuel 12:16, David is described as vishahav artzah, and he prostrated himself on the ground. In Genesis 38:9, Onan is described as vishihet artzah, and he destroyed (his seed) towards/on the ground.

- In each story, a key turning point is when (a) a judge reacts overly harshly to a case that is brought before him; (b) it turns out that he is the guilty party; and (c) he immediately recognizes his fault.

- Flocks of herd animals—tzon—play prominent roles in each story even though they are seemingly extraneous. In II Samuel 12, there are two references to tzon, sheep, in the parable of the “poor man’s ewe” and in Genesis 38, Judah is passing Tamar on the way to sheep-shearing festivities, and a goat from the flocks (gedi izim min ha-tzon; 38:17) is offered as payment for sex.

- The root “to give,” latet, plays key roles in each story.

- In I Samuel 12, it is the name of the prophet (Nathan has the unusual meaning of “he gave”) who drives the action from sin to repentance. His name appears seven times, testifying to its significance. The root also appears three additional times, in the context of describing God’s gift of the kingdom to David and once in describing his punishment.

- In Genesis 38, the verb also appears seven times and plays a crucial role in driving the narrative. The first two times, failure to give twice drives the action. Then there are four instances where it is part of fixing the problem via the deposit Judahgives to Tamar. Finally, it is involved in the birth of the dynastic heir.

- Each story concludes with a newborn child becoming the dynastic heir, in the context of an odd naming pattern. In each story, (a) two names are given; (b) the first name is given by a “mix” of man and woman[9]; and (c) the second naming is performed by a man alone.[10]

This long series of thematic and textual allusions make a strong case that the story of Judah and Tamar has something to teach us about the story of David and Bathsheba. But what precisely?

The key is to ponder what is perhaps the most remarkable link of all. In particular, in both stories the very same unique five word phrase appears, with a slight modification of word order as appropriate to its context:

va-yeira be-einei Hashem asher asah

And what he did was evil in the eyes of the Lord (Genesis 38:10)

va-yeira ha-davar asher asah David be-einei Hashem

And the thing that David did was evil in the eyes of the Lord (II Samuel 11:27)

This phrase, which appears nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible, is also noteworthy because it is quite rare for God’s state of mind to be described, especially His attitude towards a particular person’s actions. Moreover, these phrases are the climactic descriptions of sin in each story.

I would now like to suggest that they describe the very same sin. In particular, just as Onan refused to perpetuate his brother’s legacy by performing levirate marriage, David’s taking Bathsheba as his wife and especially his taking their child as his own—the action that immediately precipitates the divine condemnation above—is tantamount to erasing Uriah’s legacy when he could have perpetuated it.

Consider: the law of levirate marriage (Deuteronomy 25:5-10) states that when a man dies, his “brothers” have a mandate to perform levirate marriage lest the dead brother’s “name be erased from Israel.” Furthermore, we know from the story of Ruth that “brothers” was interpreted liberally as a moral if not a legal mandate for any relative to help the widow carry on the name or legacy of the dead man by essentially giving a son to the dead man. But who was worrying about Uriah’s legacy? Certainly not David. By taking Bathsheba as a wife and treating the child as his own, he was preventing anyone else from taking up the call to perpetuate Uriah’s legacy. In effect, David was refusing to provide “seed” on his “brother’s” behalf, just as Onan did.

Seeing David’s sin in this manner also renders it biographically significant in an especially tragic way. Up until this moment of history, the Davidic line was marked by increasing success in attending to the status of women who were left vulnerable and bereft by the loss of their husbands. One side of David’s family—the Moabite line—was founded in Lot’s failure to find husbands for his bereft daughters.[11] The other side of the family—the Judahite/Peretz line—began somewhat more auspiciously: after his initial failures, Judah was prompted by Tamar to step up. And then Ruth and Boaz bring these two lines together in a towering success—they go beyond the letter of the law to build the house of David in exemplary acts of kindness (by Ruth towards Mahlon, and by Boaz towards Ruth). David is the quintessential “yibbum-man” and all this signifies. It is thus so very poignant that his great fall is a yibbum-themed fall.

Finally, this interpretation is consistent with two puzzling details in the story. First, Nathan does not in fact accuse David of adultery, but only of “taking the wife of Uriah the Hittite (II Samuel 12:1-12).” It is not otherwise clear why this is such a major sin; but it looms much larger in the context of David’s family history and of contemporary attitudes regarding levirate marriage. Second, David’s actions are not deemed “evil in God’s eyes” (leading to His sending Nathan to rebuke David) until many months have elapsed from the time of the initial liaison and pregnancy and Uriah’s death—not until after the child is born and is described as having been taken by David “as his” (see II Samuel 11:27-12:1). R. Yaakov Medan suggests that it is not until this point that David’s descent into sin has reached its nadir, where he is attempting to profit from someone else’s misfortune.[12] I am suggesting that it is not merely that he is taking someone else’s wife and child, but that this act is a high crime by the lights of ancient near eastern society, given the institution of levirate marriage and what it signifies.

How Cover-Up Produces Sin

But surely to cast David’s sin as a failure to perform yibbum is to fall into the trap of minimizing it. Isn’t adultery even worse?

Of course it is.

But if we consider why it would not have been wise for Nathan to accuse David of adultery, we arrive at deeper lessons about the significance of the cover-up and the confession.

The most straightforward reason why Nathan did not allege adultery is that he had no evidence for it. While David’s messengers would have known that Bathsheba had visited David (see II Samuel 11:3-4), there is no evidence that this information had spread. Moreover, even if rumors had spread, and even if Nathan had special insight into what had happened (the text does not say that God informed him), he can hardly accuse David of a crime without evidence or testimony. After all, seven months had passed and no one had come forward to supply such evidence against the king. Finally, we cannot assume that Nathan knew that David would confess to his sins. David could have responded to Nathan’s rebuke by declaring “fake news!” Nathan surely would have thought this risk would be even greater were he to accuse David of a crime for which he had no evidence. But he did have evidence that David had betrayed his family legacy and contemporary norms by stealing Uriah’s legacy: it was there for the whole world to see. While David’s hidden sins may have been greater than his overt sins, those overt sins were more than sufficiently serious to merit Nathan’s rebuke.

This in turn suggests an important lesson about why cover-ups are so pernicious. David was apparently so focused on covering up the sin of adultery, it warped his sense of morality to the point that he openly engaged in actions that he should would have recognized as sinful.

Indeed, consider David’s overt sins (causing Uriah’s undignified death and having a child with his wife) from two other angles that should have been obvious to David because of their importance in the Torah: (a) the potential for abuse of authority inherent in monarchy; and (b) the importance that each individual build a household. The former theme begins in Genesis, with a series of episodes that illustrate the great fear that pagan kings would see themselves as above morality to the point that they would kill foreign men and steal their beautiful wives.[13] How could David have been blinded to the astounding fact that he did what Abraham and Isaac feared that Pharaoh and Abimelech would do?! Moreover, David was surely aware of how Deuteronomy counterpoises limits on kingly authority with the protection of the individual and his rights:[14] the general worry is that the king’s “heart will become haughty over his brothers” (Deuteronomy 17:20) and come to dominate them in various ways. And a specific worry is the nightmare scenario of a man dying (in war, presumably initiated by kings) before he has an opportunity to consummate his marriage and build a household, thereby allowing another man to take his place.[15] This nightmare is precisely what the institution of yibbum is meant to address: the protection of the legacy of each “brother” of Israel. And tragically, this nightmare is precisely Uriah’s fate, and the man responsible is the king of Israel in a quintessential act of haughtiness. What is more haughty than the conceit that one can hide one’s sins from God (cf. Genesis 3:8)?

The Power of Confession

Attention to the yibbum-theme in the story of David and Bathsheba not only helps us appreciate how covering up for sin induces moral blindness, it also helps us sheds light on the redemptive power of confession.

To see this, first consider one of the great mysteries of this story: David’s enigmatic pattern of behavior in response to his and Bathsheba’s first son’s illness and death (II Samuel 12:16-23). During the illness itself, David is beside himself, giving himself over completely to intense fasting, prostrating, and praying on behalf of the child. The court elders try to get him up from the ground—behavior unbefitting a king!—but to no avail. Indeed, his attachment to the child is so extreme that his servants are afraid to tell him that the child has passed; David must figure it out from their whispering about it. But then he surprises them again by immediately getting up, washing himself, getting dressed, going to the “house of God” and bowing, and then sitting down for a meal. Asked for an explanation, he offers only that while the child was alive, “who knows,” maybe God would save the child; but that once the child is dead, he can’t bring him back (II Samuel 12:22). This pattern of behavior is puzzling to say the least, and various commentators and exegetes struggle to make sense of it.

But let us consider this pattern in the context of a community that would have had lingering questions about the paternity of this boy. Note first: if it was not common knowledge that the child was David’s biological child, David’s dramatic devotion to the child would have clinched it. Who but a true father would pray for a child in this way? So his actions at this stage were tantamount to declaring to the world that he was the child’s biological father.

And now consider what is signaled by his decision not to mourn the child. Indeed, and quite strikingly, not only does he not mourn the child, but the text tells us that “he comforted Bathsheba” (II Samuel 12:24) even though the child was his too! This pattern of action is also tantamount to a declaration—i.e., that he is not the child’s rightful father. David seems to be declaring that in a moral sense and perhaps a legal sense, he has stolen Uriah’s child. He is proclaiming that he had wronged Uriah, the stalwart warrior.[16]

Thus David’s confession does not end with his explicit declarations of having sinned to God. He seems to transcend mere admission of sin by taking action to address it: if his sin was the erasure of Uriah’s legacy, anything he might do to remind the public that Uriah was a great officer who was wronged by the king would promote Uriah’s legacy. Any such confession would be hard for David to do—David’s reputation must necessarily fall as Uriah’s rises—but necessary if the sin is to be addressed.

This form of confession may have taken an even subtler and more powerful form. In particular, let us now consider what is perhaps the greatest puzzle pertaining to the story of David and Bathsheba: how and why would a king (David) allow a scribe (Nathan) to publish chapter 11 of II Samuel, where Uriah emerges as a dedicated warrior and David comes across as a scoundrel? In the first instance, we should assume that as in other ancient near eastern cultures, scribes worked for the king and were meant to write accounts that made the king look good. They hardly could be expected to write highly negative accounts of their masters, especially concerning actions that occurred completely in private! Moreover, while it is perhaps not unreasonable to expect a scribe to write negative accounts of historical kings, this does not apply when such kings were part of the same (Davidic) dynasty.[17] To be sure, rabbinic tradition implies that the prophets had full autonomy to write true accounts unfettered by kingly censorship. But we should not take this for granted. Rather, such protection of the prophetic/scribal “estate” should be regarded as a major achievement, and a great fulfillment of Deuteronomy’s vision of monarchy.

More specifically, the publication of this story can be thought of a powerful act of yibbum. Why does our text tell us that David committed adultery with Bathsheba? After all, it seems that it was not common knowledge in David’s court. And how do we know that Uriah was a great warrior who was wronged? The answer to both questions seems to be: David authorized this story to be told. Thus if our assumptions about the publication process are correct, David would have taken remarkable steps to correct his failure to perpetuate Uriah’s legacy and address his ugly abuse of authority more generally. By publicizing this story, one that would forever stain his own legacy (I Kings 15:5), he would have been promoting Uriah’s name and publicizing his abuse of authority so that it would stand forever as a warning to all future kings and leaders.

Countering the Danger of Confession

There is one final aspect to this story that is elucidated by the yibbum theme: David’s relationship with Bathsheba after their first son’s death. An enduring mystery is why it would have been legally permissible for David to marry Bathsheba if they had indeed committed adultery. R. Yaakov Medan suggests that on a moral level if not a legal one, David earned significant merit for having accomplished what Judah (and Boaz) did via yibbum: ultimately doing the right thing and “spreading his wings” of protection (Ruth 3:9) over an otherwise bereft/abandoned widow.[18] And if Judah (and Boaz) was duty-bound to provide such protection, how much more so would this have been the case for David who was to blame for the fact that such protection was needed. What kind of life and legacy would Bathsheba have had, especially if David had publicly proclaimed she was an adulteress?

Consider as well: While the institution of yibbum is ostensibly meant to promote the legacy of the dead husband, a review of the yibbum stories in the Hebrew Bible reveals that yibbum actually tended to promote the legacy of the bereft women (and their lineage) who had to take matters into their own hands in order to induce powerful men to do the right thing.[19] After all, who remembers Er or Mahlon or even Uriah today? It is Tamar, Ruth, and Bathsheba we remember. In that sense, while David’s continuing his marriage with Bathsheba (recognized as “his wife” only at this point; II Samuel 12:24) was not technically a form of yibbum, it did (a) follow on actions that promoted Uriah’s legacy; and (b) protected Bathsheba’s life and legacy. And an indicator that this ‘re-marriage’ with Bathsheba was considered a form of yibbum is that whereas Bathsheba is described as giving birth to the first son for him (i.e., David; 11:27), she is described simply as birthing a son, when it comes to Solomon (12:24). This is striking given that Solomon is in fact the dynastic heir. But it is unsurprising if we see this as a form of yibbum such that the child’s legacy is associated with Bathsheba and Uriah (as well as God and Nathan; see 12:25).[20]

But where does Bathsheba take initiative to secure that legacy? After all, in II Samuel 11-12 Bathsheba says only “I am pregnant” and otherwise exhibits little agency. The key moment seems to be when David is on his deathbed and Bathsheba and Nathan collude in inducing David to proclaim Solomon king and undercut his half-brother Adonijah who had proclaimed himself king (I Kings 1). It is quite curious that Nathan and Bathsheba are so close; there is no previous indication they had ever spoken. Even more enigmatic is that Bathsheba and Nathan refer to a promise David had made that Solomon would be the heir even though no such promise is recorded. Surprisingly, David acknowledges the promise and he acts as they request.

Perhaps in fact there was no explicit promise. Rather, what Bathsheba and Nathan are saying is that if David does not act as if the crown was promised to Solomon, his act of yibbum will be incomplete. Indeed, Nathan’s opening line to Bathsheba is that her and her son’s lives are in danger (I Kings 1:11-12); after all, the natural next step for a usurper like Adonijah to take is to kill all rivals to the throne, as well as Nathan and everyone associated with his father’s court. But their lives will be preserved if David names Solomon heir, and Solomon succeeds in assuming the throne.

Bathsheba’s assignment is not easy. Like Ruth (3:1-14), she must appear at her “levir’s” chamber when she was not invited. And she must suffer the indignity of talking to David as the young and lovely Abishag is attempting to warm him. But with Nathan reinforcing her appeal, Bathsheba succeeds in preserving her life and the life of her son, as well as their legacy. And David is coaxed into protecting their legacies as well, and indirectly that of Uriah. Thus whether or not David’s confessions were indeed sufficient to atone for his sins, they did serve to redress some of the harm he caused with those sins.

Conclusion

The text of the story of David and Bathsheba hints loudly that there is an important yibbum dimension to David’s sin lying just below the surface. The textual and thematic allusions to the story of Judah and Tamar seem so extensive as to be undeniable, and they are especially compelling in the context of David’s family history. Moreover, they help resolve several puzzles in the story of David and Bathsheba.

The larger implications of the yibbum theme are more debatable. Three possible implications have been discussed here. First, far from minimizing David’s sin, the yibbum theme suggests how David’s attempts to cover-up that sin distorted his moral vision to the point that he openly committed major moral transgressions without realizing it. Second, this yibbum theme helps us appreciate the redemptive power of David’s confession. In particular, he seems to have done more than admit that he “sinned to God” by taking painful steps to publicize his otherwise hidden thefts of Uriah’s life and legacy, and thereby to promote that very legacy. Finally, the yibbum theme suggests that David was induced (by Bathsheba) to protect her life and legacy, and thereby to address the harm he had caused.

Whether or not the reader agrees that these lessons are implied by the biblical text, they nevertheless seem general and meaningful: First, covering up sin distorts moral vision. Second, true confession of moral transgression requires difficult action that may do lasting damage to one’s reputation. Third, since it has the potential to help others, especially those who we have harmed, confession and repentance are worth the effort even if we will never know whether they fully atone for our sins.

This essay is dedicated to the memory of the author’s paternal grandmother Edith Rochwarger Zuckerman (איטה בת יעקב) whose 19th yahrzeit was observed on the 12th of Elul; and to the memory of his paternal grandfather Udah Jacob Zuckerman (יהודה יעקב בן אברהם זלמן), whose 19th yahrzeit will be observed on the 25th of Tishrei. May their memories be for a blessing.

[1] Note in this regard the allusions in Nathan’s parable of the “poor man’s ewe” to Saul’s sin (II Samuel 12:1-4), especially concerning the motivation of not wanting to spare—vayahmol—one’s sheep and cattle (compare I Samuel 15:9 with II Samuel 12:4). See also R. Yaakov Medan, “Megilat Bat-Sheva,” Megadim 18/19 (1993): 67-167, and R. Shmuel Klitsner, “Victims, Victimizing and the Therapeutic Parable: A New Interpretation Of II Samuel Chapter 12 (2013) for complementary analyses showing how Nathan’s parable is designed to make David think of Saul and how he wronged him, thus inducing him to find the rich man culpable.

[2] See Rabbi Moshe Shamah, “On Number Symbolism in the Torah,” in Recalling the Covenant: A Contemporary Commentary on the Five Books of the Torah (Jersey City: Ktav, 2013): 1057-1066.

[3] This approach is supported by three exculpatory possibilities: (a) that Uriah followed the common practice whereby soldiers divorced their wives (perhaps conditional on their deaths) before heading off to war (Shabbat 56a); (b) that “Uriah the Hittite” was not Jewish, and thus not technically subject to the laws of adultery (Medan, op cit., pp. 82-83); and (c) that Uriah deserved to die because he was insubordinate in his words (seemingly calling the general Joab his “master” in front of David) and possibly his actions (not going down to Bathsheba when commanded by the king; Shabbat 56a).

[4] For review, see Rav Amnon Bazak. “Chapter 12 (Part III) The Attitudes of Chazal and the Rishonim Toward the Episode of David and Bat-Sheva.”

[5] Medan, op cit., p. 136.

[6] Abarbanel ad loc., II Samuel 11:14.

[7] Parallels b, c, f, and a version of l are noted by Rav Amnon Bazak, “Chapter 11 David and Bat-Sheva (Part II).”. Rav Bazak also notes the most important parallel, concerning God’s judgment of Onan and David, as discussed below.

[8] Various commentators understand einayim (Genesis 38: 14,21) as referring to springs. Note also that David’s suggestion that Uriah go home and “wash your feet” (II Samuel 11:8) is widely interpreted as an allusion to intercourse. And note that Ruth too washes herself (Ruth 3:3) before going to Boaz’s bed.

[9] In Genesis 38:28-29, a woman—ostensibly the midwife but perhaps Tamar—provides the rationale for Peretz’s name, but a man—presumably Judah—formally names him. In II Samuel 12:24, Solomon is named by both David and Bathsheba [the literal text says that “he” named him, but the Masoretic note has us read it as “she” named him].

[10] In Genesis 38:30, this is a man (ostensibly Judah again), providing a name to the second twin, Zerah. In II Samuel 12:25, this is Nathan giving a second name to Solomon, Jedidiah.

[11] See Seforno and Kimhi on Genesis 19:31, and see Harold Fisch, “Ruth and the Structure of Covenant History,” Vetus Testamentum 32 (1982): 425-37.

[12] Medan, op cit., p. 144.

[13] See Medan, op cit., pp. 87-90.

[14] See Joshua A. Berman, Created Equal: How the Bible Broke with Ancient Political Thought (New York: Oxford, 2008).

[15] See Deuteronomy 20:7, 28:30.

[16] It is unclear when David would have hatched this plan. But item k in our list of allusions is suggestive, in that it links David’s praying for his son with Onan’s destroying his seed. Perhaps the text is hinting that it was at this moment of prostrating himself before God that David realized that he needed to do the opposite of Onan (who was hiding from God): to promote Uriah’s legacy rather than destroy it.

[17] This last assumption parts company with those adopted by critical scholars (e.g., Baruch Halpern, David’s Secret Demons: Messiah, Murderer, Traitor, King (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003) who understand Samuel as hagiography designed to mask David’s sins with false virtues. Such approaches have yet to come up with a plausible explanation for why chapter 11 of II Samuel would be included (see David A. Bosworth, “Evaluating King David: Old Problems and Recent Scholarship,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 68 (2006): 191-210).

[18] Medan, op cit., p. 145.

[19] The same is true for the daughters of Zelophehad (Numbers 27:1-11). They succeed in perpetuating their father’s legacy, but the indirect effect is to promote their own legacies.

[20] This ‘pseudo-yibbum’ outcome may provide something of a solution to a very difficult dilemma (thanks to Davida Kollmar for posing it): Once Uriah had died due to David’s instructions to Joab, what should David have done? If he confesses at that point (or even after the initial adultery), how will Bathsheba and her son be protected? But if he does not confess, how will Uriah’s legacy be protected? Ultimately, the answer is unclear. What does seem clear is not the one that David chose—i.e., to take Bathsheba and the son as “his” rather than Uriah’s. It is possible that if David had turned to (Nathan and) God at that point, he would have been guided to a resolution along the lines of the one that is ultimately achieved via Solomon. And perhaps this would have occurred via the first child. But it is of course impossible to know.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.