Zev Eleff

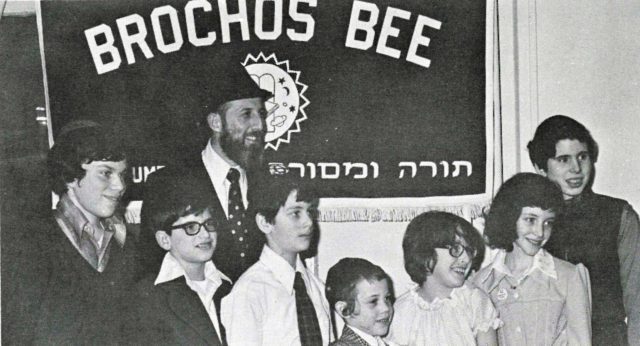

In March 1971, Torah Umesorah held the inaugural Brachos Bee for Orthodox day schools in New York. It was Rabbi Dovid Price’s idea. Four years earlier, the principal of Yeshiva of Prospect Park had concocted the blessing bee for his Brooklyn-based school. It had worked. The Prospect Park youngsters embraced the game. To expand the competition, Price recruited about a hundred elementary and middle schools to quiz their students on the proper blessing to recite on all kinds of foods and other miscellanea like seeing rainbows and oceans.

School competitions narrowed the field. The pupils hailing from fourteen schools who managed to memorize blessings for the tougher items like peaches and cream, ice cream sandwiches, and roasted chestnuts moved on to the finals at Torah Umesorah’s headquarters on Fifth Avenue. There, Price and his team of judges led a series of written and oral exams before crowning male and female champions in three age brackets.

Of course, Price and Torah Umesorah patterned their competition after the spelling bee. The Brachos Bee was therefore a clever expression of acculturation. Or, a “coalescence,” as Sylvia Fishman and Yoel Finkelman have each termed it. The Brachos Bee drew from American forms of intense competition—historians long ago documented America’s disavowal of Britain’s “gentlemanly sport” culture—and child-centered education. The contests helped inculcate religious observance and standardize halakhic practice. These aspects of the Brachos Bee also ensured that a variety of Orthodox enclaves could cooperate with one another and absorb American culture.

Adapting the Spelling Bee

The spelling bee is an old institution. Americans in the early nineteenth century made use of spelling competitions as a savvy method to drill youngsters—immigrants and first-generation Americans—on English words and pronunciations. With the aid of radio, spelling bees gained renewed popularity in the interwar period. In 1925, the National Spelling Bee began in Louisville, Kentucky, leading educators to herald the “Spelling Bee’s Revival.”

In 1941, the E.W. Scripps Company acquired the sponsorship of the popular contest. In 1953, it became the custom for the National Spelling Bee winner to visit the White House and with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. During the 1960s, the champions routinely appeared on a segment of the Ed Sullivan Show. It was, then, something of a cultural phenomenon. In December 1969, for instance, the National Spelling Bee loomed large in the very first Peanuts film, much to the chagrin of runner-up Charlie Brown.

Torah Umesorah looked to claim a version of the successful spelling bee as its own. Whereas the spelling bee was intended to Americanize its young participants, the Brachos Bee aimed to inculcate a baseline of religious observance. After all, Orthodox Jews tend to recite a lot of blessings during their trice daily prayers and before eating food. Shalom Auslander’s recollection of a schoolwide Brachos Bee match underscores the parallel between the two contests:

The blessing bees began easily. Dov Becker got tuna (shehakol, the everything-else blessing), Ari Mashinsky got matzoh (hamotzei, the blessing for bread), and Yisroel Tuchman got stuck with kugel, which he thought was ho-adamah—food from the earth—but really was mezonos—the blessing on wheat. Three other kids got taken out by oatmeal, borscht with sour cream claimed two others, and by the end of the first round, almost a third of the students were already back in their seats.

The competitive spirit characterized the boys’ and girls’ Brachos Bee competitions. For example, the New York Times reporter depicted the following fierce scene among the Junior Girls Division in March 1976:

Fast and curious the questions came: what is the blessing appropriate to almonds, American cheese, angel food cake, apples … Down went contestants—on buckwheat, chives, éclair eggplant, grits, kasha, parsley. Finally, Reana Bookson, aged 6, stumbled on rhubarb, leaving Elaine Witty, 8, triumphant winner.

The Brachos Bee, then, was simultaneously an entertaining method to obtain a better command of Jewish blessings and a Judaization of a popular American educational pastime. This sort of cultural coalescence was the hallmark of a particular brand of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. Torah Umesorah provided support and services to all types of Orthodox day schools but its administration and rabbinic leadership identified with the Orthodox Right. This cohort eschewed affiliation and interaction with the non-Orthodox and non-Jewish realms.

Take, for instance, Rabbi Yaakov Feitman’s description of “Baseball Syndrome.” Writing in the April 1976 edition of Torah Umesorah’s Jewish Parent, the writer lamented how “Baseball, that most American of pastimes, recurs again and again in American Jewish literature as a metaphor of Americanization—and, in the process, de-Judaization.”

Yet, the Orthodox Right did incorporate aspects of American culture, so long as its adherents could reinforce its steady need to remain apart from it. The Brachos Bee was proof.

Their moderate coreligionists did not usually agree with this stance. The Orthodox rank-and-file were less sanguine about such separatism. True, Orthodox Jews established their own boy scout troops, but mostly to accommodate kosher eating and scheduling prayers. Children from Religious Zionist homes also competed in Israel’s International Bible Contest—known as the Hidon Ha-Tanakh—but this had no American analogue.

Many Orthodox Jews at that time embraced healthy participation in mainstream American culture. In the spring of 1963, Orthodox Jews rallied behind a group of Yeshiva University students competing on NBC’s College Bowl quiz show. Thousands tuned in and hundreds gathered in front of the Midtown Manhattan television studio to cheer YU’s Mighty Mites squad as it stunned Louisville, trounced UNLV, and then lost a close one to the eventual season champion Temple University.

Less than a decade later, Dovid Price’s Brachos Bee offered something different. It was patterned after an American game but intended just for Jews. Despite this, Orthodox parents and educators liked that the Brachos Bee seemed to unite all varieties of Orthodox young people. The Modern Orthodox competed with the children of the so-called Yeshiva World. The rare ecumenical opportunity convinced Orthodox Jews that they could duel alone, away from non-Jews and other non-Jewish influences.

Similar forces guided the formation of New York’s so-called Yeshiva Basketball League (officially, the Metropolitan Jewish High School League) and the emergence of a multi-genre Orthodox popular literature. Yet, neither sports (too coeducational for the Orthodox Right) nor Orthodox books (too culturally narrow for the Modern Orthodox) could compare to the Brachos Bee’s appeal to a wide swath of Orthodox children and teachers. Its focus on Jewish literacy and good-natured competition for elementary and middle school-aged girls and boys (in separate divisions) was deemed too wholesome to resist.

Blessing Along the American Orthodox Frontier

In 1972, Price expanded the competition beyond New York, and dug deeper into Torah Umesorah’s non-profit coffers to sport prizes like tape recorders and wristwatches. The “out-of-towners” fared well against the Gothamites. Finalists for the second year’s championships hailed from Milwaukee, Montreal, New Orleans, and San Diego.

The competition grew. The following year’s event included more than 400 schools. Affording themselves a moment of self-adulation, Torah Umesorah leaders congratulated themselves for a contest that had “evoked widespread interest and admiration.”

San Diego’s participation was something of an aberration. Most West Coast schools were located too far away to compete in the New York-based competition. In 1975, Los Angeles’s Hillel Hebrew Academy and Emek Hebrew Academy hosted their own Brachos Bee contest amid considerable fanfare. The Emek match was judged by Israel’s Chief Rabbi Ovadia Yosef. Rabbi Yosef quizzed the children on basic blessings and made sure the pupils knew the “historical roots and spiritual concepts involved.”

The craze was soon formalized in the West. In May 1977, Rabbi Eliezer Wenger and Torah Umesorah formalized the West Coast section of its National Brachos Bee enterprise. While serving as a teacher at New England Hebrew Academy in Boston (both Wenger and Hebrew Academy were affiliated with Chabad), Wenger grew enchanted with the Brachos Bee idea. After relocating to San Francisco, Wenger convinced Torah Umesorah to migrate the blessing bee westward. He recruited schools from Arizona, California, and Oregon.

Wenger also published his popular two-volume Brachos Study Guide to level the playing field and encourage youngsters to memorize their blessings. Along with an NCSY blessing book, Wenger’s textbooks became the go-to manuals for the Torah Umesorah competition. Withal, Wenger published nine editions of the guidebook from 1978-1991.

The blessing books were also very helpful for Orthodox educators. It helped familiarize the less culturally inculcated youth to kosher cuisine. Wenger recommended that the “teacher should take time to explain about certain foods and if possible to bring a sample to class.” The textbooks also introduced Jewish children to leading luminaries like Rabbis Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Moshe Feinstein, and Pinchas Hirschsprung. The author also offered some guidance on how to drum up excitement for the Brachos Bee:

To maintain the excitement of the Brochos Bee, it is necessary to constantly display pictures of foods on the classroom walls and bulletin boards. An excellent source for beautiful color pictures of fruit and vegetables is your local grocer, supermarket or fruit store. Ask them to save for your use extra display pictures which they obtain from their distributors. These pictures are large, colorful and impressive. Writing to Government agencies, dairy associations and the various food manufacturers can also prove productive.

In its first two years, the West Coast showdown took place in the Bay Area. The competition received considerable attention from Jews and non-Jews. In 1978, San Francisco Mayor George Moscone greeted the finalists, praising “their determination to preserve the sturdy traditions of Judaism.” The pageantry helped convince all those involved that their Brachos Bee was no less American than its spelling bee counterpart.

Rabbi Wenger emerged as a Brachos Bee pied piper, much to the delight of Dovid Price and Torah Umesorah back in New York. In 1979, Wenger accepted the principalship at Landow Yeshiva-Lubavitch Educational Center in Miami Beach. Once settled, he founded the Florida division of the Brachos Bee. Wenger believed in the power of blessings. To him, it was no mundane religious act. He taught his students—and anyone else who would listen—that the many blessings recited by observant Jews remind them to be grateful for food and all other forms of sustenance. “I think if more people realized these things and were thankful,” told Wenger to a Fort Lauderdale newspaperman, “they’d lead better lives.” He was also proud of the range of Orthodox children who competed in the annual contest.

In Florida, Wenger followed the same successful model that he had executed in the West Coast. In May 1982, Miami Beach Mayor Norman Ciment—Torah Umesorah happily reported that Ciment was the “only Shomer Shabbos mayor in the United States”—attended the final round of the Florida Brachos Bee. In his introductory remarks, Mayor Ciment extolled Wenger and the other program organizers for starting a competition that “reinforces emphasis on those ideals and ethics which give religion its true meaning, teaching holiness and humanity.” In other words, the Brachos Bee was just as Jewish as it was an American-styled game.

In 1984, the itinerant Wenger moved to Cincinnati and formed the Midwest Brachos Bee competition. Also sponsored by Torah Umesorah, Wenger assembled schools from Cleveland, Chicago, Columbus, Detroit, Indianapolis, and Louisville. The Midwest region also provided a testing ground for Torah Umesorah to experiment with computerized sections of the quiz.

Competing in the Bee

Still, Wenger—for all his bountiful and boisterous Brachos Bee pride—could still not compete with Philadelphia’s rabbinic firepower. In the 1980s, the local Torah Academy was the premier training ground for Brachos Bee champions among the 500 schools and 4,000 boys and girls who faced off in the annual contest. Back then, Torah Academy served a wide range of Orthodox children, never pushing too hard on “divisive” issues like Zionism or coeducation, at least in the younger grades.

In 1981, Ahron Shlomo Svei won the Senior Boys Division of the Brachos Bee. He was the son of Rabbi Elya Svei, the head of the Talmudical Yeshiva of Philadelphia—the “Philly Yeshiva”—and member of the conservative Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. Apparently, Rabbi Svei did not mind the competition and interaction with Modern Orthodox Jews.

Two years later, Rabbi Svei’s younger son, Mayer Simcha, claimed another Brachos Bee championship for Philadelphia. The youngster memorized more than 1,000 blessings for foodstuffs, and other blessings on smelling and seeing things. The junior Svei earned a perfect score on the final exam and outmatched his counterparts in the oral round. “I’ve had good role models,” said the 12-year-old, whose pastimes included Torah study and basketball. “My brother has been a good influence and my father is a rosh yeshiva, a head rabbi for the Philadelphia yeshivas.”

In addition to Mayer Simcha Svei, Eliyahu Gold, Torah Academy’s Shlomit Zeiger and Malka Kamenetsky also placed high in their respective division finals. Most of these children were raised in well-known rabbinic households.

In 1984, Torah Academy boasted another blessing champ. That year, Yehuda Mandelbaum, 10, won the Intermediate Boys Division. Mandelbaum’s triumph was far more understated than the Svei brothers. “I wasn’t too confident because there were so many other kids,” explained Mandelbaum, “and I had only two weeks to study while most others had more,” he said. “I thought I’d come in fifth place, not first.”

But competition was a means to elevate all contestants. Boys in the Intermediate Division were trained to answer questions with cleverer questions. For instance, when a judge asked for the blessing on applesauce, the youngster atop the podium offered a counter-question: “Home-made or store bought?” To borscht: “with or without potatoes?” Perhaps trickiest of all was pizza. Judges expected the following response: “One slice for a snack or a two or three for a full meal?” More confounding, still, was Kellogg’s Crispix, but merciful Brachos Bee organizers left that rice-corn combination food off competition blessing lists.

All Bees Come to an End

Torah Umesorah disbanded its National Brachos Bee competitions sometime in the 1990s. By this time, there were too many Orthodox day schools to include in the regional rounds. In addition, teachers and school administrators figured that they could create sufficient excitement and effectively teach the laws of blessings in schoolwide or citywide Brachos Bees without the expense and inconvenience of a final round at Torah Umesorah’s offices.

For instance, Chicago’s Associated Talmud Torahs—and local educator, Rabbi Yitzchok Bider—formed a local competition for Orthodox day schools in 1993. The inaugural competition rewarded champions with a $50 Israel Bond. The finalists received an ArtScroll blessing book and all participants received NCSY’s Guide to Blessings pamphlet. From 1993-1997—the ATT ran four competitions (it was temporarily suspended in 1996), attracting about 40-50 middle school-age girls and boys who dutifully studied from a makeshift blessing textbook authored by a local Arie Crown Hebrew Day School teacher.

Today, scores of schools hold a Brachos Bee, many as part of yearly Tu Bi-Shevat festivities. The Brachos Bee is no longer a national event, bringing together Orthodox Jews who may not otherwise agree or cooperate with one another. Still, the Brachos Bee remains a creative coalescence of American and Jewish ideals. It, therefore, symbolizes the unique way that Orthodox Jews adapt and embrace their American surroundings.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.