Michael Bernstein

Pre-introduction: Background and Claims

Before launching into the academic voice of the present article, I want to speak personally to the reader about the background to this project and about the different kinds of claims it will make.

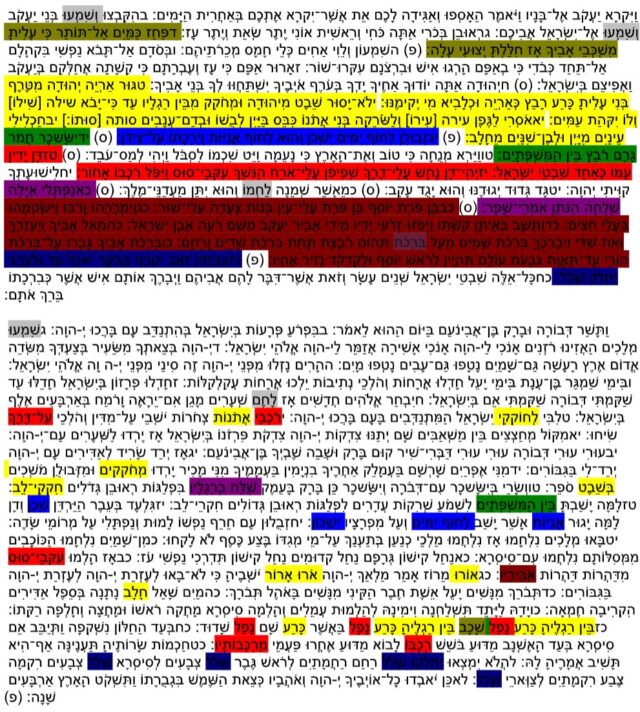

I first noticed the intertextuality between the two passages under discussion, the blessings of Jacob in Genesis 49 and the song of Deborah in Judges 5, in my early teens. I assumed from the very start, through a traditional lens on Tanakh, that the blessings of Jacob were the earlier text, but I could have been convinced otherwise if there had been a compelling case in the scholarship. Regardless of the direction the intertextuality flowed, I was sure someone would have something to say about it. I had access to a wide range of both traditional and modern commentators, but could not find any who described what I had picked up on. Some individual word overlaps were noted by modern scholars, but there was no acknowledgement of an intentional, sustained phenomenon, i.e., one passage overtly mining the other for material – while, frustratingly, much of the literature seemed more interested in reading either passage in contrast with the blessings of Moses. At that time, my analysis existed solely as a slim stack of photocopied Tanakh pages, with color-coding done in highlighter to mark word overlaps – the most rudimentary version of the visual aid that accompanies this article. I put the pages in a drawer until I could figure out what to do with what I had noticed.

In college, I had access to more robust digital research tools, and a much better understanding of the different a prioris of “frum” scholarship versus academic scholarship, and I pursued this topic as a term paper. That was when I figured out one possible cause for the lack of scholarship on this observation. The kind of modern academic scholar I would have expected to note and analyze this intertextuality likely dates the song of Deborah really early, potentially ‘earliest piece of poetry in Tanakh’ early, and dates the blessings of Jacob (relatively) later. The blessings of Jacob constitute a prophecy about later generations of each tribe, and when many modern scholars see a passage of prophecy, they see it as their job to determine which events a significantly later composer is alluding to retrojectively, especially when it comes to something with obvious consequences, like the blessing of Judah setting the foundation for the lineage of kings. It’s all too easy to approach this text listing all the sons while asking, “How can we mine this allusive poetic text about the tribal patriarchs for everything it indicates about the history of the territories bearing tribal names, about which it was really written later on?”

With that said, I still wonder why there isn’t more scholarship on the shared vocabulary of these passages; after all, even if the song of Deborah is extremely early, one could still hypothesize that the flow of influence runs the other direction, and that the blessings of Jacob borrow from the song of Deborah. The overlaps seem to me to be too pervasive to ignore. And yet, this observation has gone unpublished (to the best of my knowledge), and certainly no work has come out mapping the allusions and attempting to understand or explain their distribution.

I revisited my analysis in early 2020 for a lecture version of this presentation, updating the list of allusions and expanding the analysis in Part IV. This article combines the original paper with the updated analysis from that lecture.

This article makes one primary claim, and that is the simple but firm literary-analytical assertion that these texts are intertextual, with the blessings of Jacob as the source text from which the song of Deborah is consciously borrowing (though a reader could accept the observation of intertextuality and withhold judgment on the relative dating). My suggestion of a rhetorical basis for the distribution of shared terminology in the song of Deborah – my attempt to explain the “why” of the intertextuality in the context of the narrative – constitutes a secondary claim. Other explanations are surely possible, and I hope to hear them in the future.

This article also finds reason, in the course of its analysis, to make two tangential claims. I’ll put a fairly tight date range on the events described in the song of Deborah. I’ll also assert that we should reject the reading which projects sexuality onto the interaction between Yael and Sisera in Judges 4 based on prima facie suggestive language in the song in chapter 5. These two claims I have confined to footnotes; the reader should consider them ancillary to the core argumentation of the article.

I. Introduction

The “Song of Deborah” in Judges 5 has long been recognized as a distinctive text, not only relative to the Hebrew Bible overall but even within the considerably smaller corpus of biblical poetry. Much has been written on the matter of dating this work, with many sources identifying it as one of the earliest poetic passages in Tanakh.[1] Most of these identifications focus on archaic features of the song’s language. Judges 5 is often discussed alongside two other early-dated works of biblical poetry: the blessings of Jacob in Genesis 49 and the blessings of Moses in Deuteronomy 33. Surprisingly, although some readers of Judges 5 see significant connections between Deborah’s song and the Mosaic blessings, discussion of the song’s relationship to Jacob’s blessings is poorly represented in the scholarly literature. I doubt this is because I am the first to notice the extent of this relationship – the odds against that possibility are incredible. Perhaps presumptively dating Judges 5 earlier than Genesis 49 has, to this point, gotten in the way of an extensive, on-its-own-terms analysis of the intertextual relationship between these poetic passages. Whatever has kept such an analysis from being undertaken (or, if it has been undertaken, from being accessible), there can be no doubt that this is a project long overdue.

The link between Jacob’s blessings and Deborah’s song is, at first glance, an elementary and unimpressive one: both texts name, and poetically describe, the tribes.[2] This simple similarity, however, runs deep. The vocabulary of Judges 5 is not just comparable to that of Genesis 49; it is strikingly similar. The evidence for the two works’ intertextuality comes from multiple aspects of this linguistic and terminological similarity: 1. the occurrence in both texts of a rare word or phrase (especially when paired with a tribal name); 2. the regularity with which terms found in Jacob’s blessings appear in Deborah’s song; and 3. the variety of such terms as they are found throughout Judges 5.[3] The latter two phenomena are so pronounced that Genesis 49 terms appear, several times, even outside (5:9-10; 22-30) the portion of Deborah’s song (5:14-18) which parallels the tribe-by-tribe aspect of Jacob’s blessings. Our treatment will first examine the allusions evident within the “Tribes” section of the song, and then consider the presence of allusions which have “leaked” to the rest of the song, as well as the implications this has for reading the work.

II. Mix-and-Match – Tribe Names and Allusions in 5:14-18

The appearance of tribal names (Ephraim, Benjamin, Machir [son of Menashe], etc.) in this section is only the barest hint of the link between the song and Jacob’s blessings; such similarities are certainly not sufficient cause to assert an intertextual relationship. But the appearance of these names alongside key Genesis 49 words and phrases is the most straightforward evidence that some relationship does exist.

A curious feature of this co-occurrence is the metastasis of several noticeably borrowed words, resulting in some unexpected juxtapositions. Especially with a premise of intertextuality, or even of traditional tribe-characterizations, one expects a given word or term to appear in Deborah’s song in tandem with the tribe to which it relates in the blessings of Jacob – but here the terms have been shuffled around and matched with different tribes. This disjunction of borrowed term from original referent is, perhaps, yet another reason that the full extent and significance of the link between the two poetic works has not been highlighted in the past – as well as, undoubtedly, one of the reasons that so many suggested emendations are extant in the scholarly treatments. Yet, I believe that this apparent oddity, far from suggesting a corruption of the text, serves to further support the claim of intertextuality, both by prompting examination of the rest of the song and by demonstrating that the presence of allusions therein is not happenstance. The latter point, and its relevance to the “mix-and-match” phenomenon in the Tribal section, will be revisited and further developed in part IV.

Verses 14 and 15 in the song of Deborah mention the tribes of Ephraim, Benjamin, Machir (i.e., Menashe), Zebulun, Issachar, and Reuben. The allusions to Jacob’s blessings in these verses, however, consist of three Judah references and one (less-overt) Naphtali reference. Genesis 49:10 is the source for all of the Judah terms: מחקקים and שבט in 14 are fairly concrete, and חקקי-לב in 15, though not as blatantly similar to מחקק in Genesis 49:10, is nonetheless significant. The occurrence of the poetically-complementary term חקרי-לב in the following verse is an example of wordplay suggesting the author’s desire to draw the reader’s attention to the words. The root חקק occurs twice in the Tribal section and once elsewhere in the chapter: לחוקקי ישראל in verse 9. This Judah term appearing throughout the song calls to mind Jacob’s blessing Judah with the privilege of leadership – despite the absence of the name Judah itself, his blessing is evident (see part III).

Verse 15 also contains an echo of Jacob’s blessing to Naphtali, who is described in Genesis 49:21 as אילה שלוחה, a “gazelle sent-forth” – here, the tribe of Issachar is said to have fought valiantly under the generalship of Barak with the phrase שלח ברגליו, which most translations interpret as “sent forth (shulah) at his [Barak’s] feet,” into the valley. This שלח is in proximity to Naphtali’s name in verse 18. Some (Christian) translations emend the second occurrence of Issachar’s name in verse 15 to Naphtali, based entirely on the evidence that Barak himself was a member of the tribe of Naphtali (4:6a).[4] We needn’t endorse such an emendation, but the consensus that Barak was a member of Naphtali is, certainly, even more reason to consider שלח ברגליו an allusion to the blessings of Jacob.[5]

The most glaring evidence for the intertextuality of Genesis 49 and Judges 5 is in verse 16 of the song of Deborah. Here we find the unusual phrase בין המשפתים, “between/among the sheepfolds,” which occurs only in this verse and in Genesis 49:14, where it is applied to Issachar. On the strength of this fact, Barnabas Lindars comes close to appreciating the potential link between the two poetic works. But Lindars is troubled by the coupling of this term with Reuben (he even refers to “the relation to Genesis 49” as a major “difficulty” of interpreting verse 16) and uses the occurrence of the ostensibly equivalent phrase בין שפתים in Psalms 68:14 to suggest that “if we reject the idea of direct literary dependence between these three passages, the phrase can be accepted as a proverbial expression for people who stay at home.”[6] That understanding of the phrase definitely makes the most sense, although I believe Psalm 68 is a distracting element here.[7] The usage in reference to the tribe of Reuben, by which Lindars is troubled, is just the most noticeable instance of the terminological “mixing and matching” phenomenon that pervades the chapter. In my view, the use of בין המשפתים in the song of Deborah is a sign that the author not only consciously utilized the language of Genesis 49, but also wanted the reader/listener to make that connection; this is no case of idle repurposing or recycling of idiom – rather, it is a case of calculated and purposeful reference to an existing literary work with which the author expects their audience to be familiar.

Zebulun, already mentioned in verse 14, is mentioned once more in the very first word of verse 18. Yet, the terminological and linguistic allusions to the blessing given to Zebulun in Genesis 49 are concentrated in the previous verse (17). 5:17 features nearly every key word found in Jacob’s blessing to Zebulun: אניות is present, as is לחוף ימים.[8] The word ישכון is there, along with another instance of the root שכנ earlier in the verse. Yet these terms occur in a verse which deals with the tribes of Dan and Asher, not Zebulun.

III. Leaking – Allusions Outside the Tribal Section

The author’s allusions to tribal blessing terms from Genesis 49 are not confined to the “Tribes” section: some seem to have “leaked” into other parts of the song. As noted above, the first of these is the Judah-term מחוקק’s echo in 5:9.[9] This is far from the extent of Judah’s presence in the song; Judah and Dan show up with especially high term-density throughout; we will therefore examine these tribes’ terms first.

5:10’s use of רכבי אתנות echoes both רכבו of the Dan blessing and אתנו of the Judah blessing. The root רכב is important to the intertextuality case; not only is it precisely extant as רכבו (and possibly evoked as מרכבותיו, both in 5:28), but its appearance in 5:10 is shown to be likely as an allusion-word by that verse’s use of the Dan-term על-דרך, which appears in Genesis 49:17 as עלי-דרך. Dan’s presence in the “leaked” allusions is further attested by the term עקבי-סוס in 5:22, As with Issachar’s בין המשפתים, this term עקבי סוס is found only in Genesis 49 and Judges 5.

It is possible that the use of the hapax legomenon מדין middin in 5:10, pluralized with an unexpected nun sofit to juxtapose dalet and nun, is a further wink to attentive readers. Middin is widely understood to mean “cloths,” “carpets,” or some other textile product based on the word מד, mad, (garment). Usual patterning would produce the plural maddim or middim with a mem sofit, but the form is Aramaized here, producing a visual evocation of ידין from the Dan blessing.[10]

The word for milk, חלב, is obviously relevant to the story of Yael and her successful ploy to slay Sisera; despite the fact that we might expect this word to appear in the song, however, its placement in 5:25 may be seen as yet another allusion to the blessing of Judah, which includes חכלילי עינים מיין ולבן-שנים מחלב. The grounds for this suggestion lie primarily in the much-stronger case for allusion in the adjacent verse 27. There, two Judah-terms occur, each more than once: בין רגליה, echoing מבין רגליו of Genesis 49:10, shows up twice; כרע, a key verb in Genesis 49:9, shows up three times (שכב in v. 27 also evokes משכבי אביך from Reuben’s blessing in Genesis 49:4). [11]

The remaining non-Tribal-section allusions are to three parts of Genesis 49: the Simeon/Levi passage, the Joseph passage, and the Benjamin verse. מחצצים in 5:11 echoes חצים from Joseph’s blessing, and אביריו at the end of Judges 5:22 reflects אביר. Both instances of בגבורים (in 5:13 and 5:23), as well as בגברתו in 5:31, bring to mind גברו, also from the blessing of Joseph. The opening words of 5:23, אורו… ארו ארור, recall the “blessing,” such as it is (or, more accurately, is not), of Simeon and Levi, in which the root ארר figures prominently.

The Benjamin allusion, like the חלב one, consists of a phrase (about the spoils of battle) that we might have expected to find in this text anyway: יחלקו שלל and the subsequent threefold repetition of the word שלל in 5:30 bring to mind יחלק שלל of Genesis 49:27. These last few allusions cannot be discounted – certainly not in light of the several other allusions found outside the “Tribes” section.

One other possibly intentional evocation is worth mentioning, and that’s the echo of ושמעו אל ישראל אביכם (Genesis 49:2) in עד שקמתי דבורה שקמתי אם בישראל (Judges 5:7).[12] It will be meaningful to the rest of our discussion to keep in mind that Deborah, while channeling the poetic voice of Jacob/Israel the patriarch, is explicitly cast in a parallel matriarchal role vis-a-vis the people who bear his name.

IV. Scattering in Order to Unify

The two apparent, and apparently distinct, phenomena within the song of Deborah noted above – the mismatching of tribe names with various Genesis 49 terms and the appearance of terms from the tribal blessings of Genesis 49 outside the Tribal section – should be seen not as disparate (and thus, perhaps, individually troubling) features of the work. Rather, they should be considered two aspects of a single technique by the song’s composer. This technique is employed consciously, calculatedly, and with a thematic goal. It is a tactic intended to underscore the unifying message of the work.

Both the metastasis within the Tribal section and the “leaking” of Genesis 49 language to the non-Tribal section are aspects of a scattering effect, whereby the poet intentionally distributes key words and phrases throughout the song. The apparent mix-and-match feature of the Tribal section is, in this light, merely an example of this scattering technique – albeit an example which a) is difficult to identify as such, precisely because the tribal names distract modern readers and suggest that the connections within verses 14-18 are of a different nature, and b) boasts both a higher concentration of terms and more overtly-Genesis 49-related terms, perhaps also due to the conscious juxtaposition with tribal names.

Judges 5 reflects an Israelite society which is still fundamentally tribal/territorial. Rather than approaching the text with the relative geographical locations of the various tribes foremost in our minds, as many (including Lindars) have done, we should instead approach the text from a leader’s standpoint. To be fair, it’s quite reasonable to encounter the Tribal section and instinctively reach for one’s biblical atlas to orient one’s reading geographically – the Reuben territory, Gilead, the coastline (hof yammim), etc. – and base an approach to understanding the substance of the song on the assumption that there’s primarily something territorial at work. But instead, we should think about the character of Deborah, and about the demands of holding a leadership role (particularly one not centered around military prowess), at this critical point in the Tanakh’s narrative of the Israelite national story.

Deborah is described occupationally in chapter 4. She is ishah nevi’ah, a prophetess – and without many predecessors to emulate. In fact, she is only the second Israelite prophet inside the Holy Land. She does the job of a shofeit, a chieftain (hi shofetah et Yisrael), but she is not a typical shofetet in the model of Ehud; she is not herself a military figure. Barak fills that role. Instead, she very literally does the work of a shofeit in its core meaning; she’s the only shofetet we ever find described as engaging in actual mishpat, issuing legal or religious decisions (Judges 4:5). The people who come to her for counsel are not called by any tribal affiliation. They’re simply all called Israelites, Benei Yisrael. She is the point of commonality at that time for all of Israel.

A challenge inherent to leadership in such a situation is the difficulty of bringing people from different demographics, with different interests, together for a common purpose. What is it to be a leader during this time, before the formation of the United Monarchy, when there is a sort of confederation of tribes but no established unifying body? And what is it to be an Israelite, as they band together at certain pressure points of military necessity but otherwise seem to largely identify as members of a given tribe? What could the author have sought to accomplish by scattering the Genesis 49 “blessing” terminology? What is the point of alluding so strongly to an existing poetic composition if the allusions themselves are so thoroughly shuffled and redistributed?

There is much to gain at this point from briefly thinking about Judges as a work overall. The Israelites have settled in the Land, the conquest is done, yet their hold on power is not cemented. There’s no national military cohesion. Note that these chieftains not only don’t rise to influence hereditarily, but they don’t even come from one particular tribe – they come from all over. Each chieftain is fighting off the dominion of regional rivals on different fronts. Othniel from Judah fights Aram, Ehud from Benjamin fights Moab, Deborah alongside Barak from Naphtali fights Canaan, Gideon from Menasheh fights Midian, Jepthah of origins uncertain fights Ammon, Samson from Dan fights the Philistines. (From time to time, Israelites fight other Israelites: Gideon destroys two towns that decline to lend him their aid; Jephthah and the tribe of Menasheh go to war with Ephraim. The story of the Benjaminite War also turns on an axis of tribal conflict, to say the least.)

The end of Joshua’s military campaign was the end of the unifying force of a national military objective. Each faction went to start settling its new homestead: “When Joshua dismissed the people, the Israelites went to their allotted territories and took possession of the land” (Judges 2:6). The period of the shofetim is a period of instability for Israelites broadly, in terms of national security. Yet, something does stabilize during this period: tribal identities in distinction from one another and sometimes in conflict with one another.[13]

The song of Deborah explicitly lauds certain tribes and chides others. In a climate of struggle and warfare especially, this might seem an unwise choice. After all, inter-tribal strife is the last thing an Israelite leader should be cultivating, particularly when tribal unity and cooperation are paramount to the success of the Israelites’ conquest and settlement project overall. It is this potential tension which the scattering of Genesis 49 “blessing” allusions seeks to neutralize. When the character of Deborah sings this song, she’s not just acting as a poet – she’s acting as a leader and as a prophetess-advisor to a national population made up of people with individual tribal identities. Her responsibility is to that national whole, even if the individuals comprising it don’t necessarily always feel responsible for one another.

The situation called for a victory song, and, indeed, some tribes had earned praise while others deserved to be scolded. For Deborah, in her position as leader of a national constituency consisting of smaller, discrete tribes, this was obviously a perilous path to tread. At this point in time, the Israelites were still many years away from unifying as a kingdom.[14] Tribal identities and loyalties were primary; national loyalties were secondary. Some balance needed to be struck, or some gesture offered, if the song was to be true to the events it commemorates while at the same time managing not to foster (further?) fragmentation or resentment among the tribes.

The solution to this problem is found in the scattering technique employed by the song’s author. By echoing the blessings bestowed by Jacob on his children in Genesis 49, the poet evokes both a masterful work of existing poetry and the most crucial instance in which all of the tribal forefathers were gathered in one place to hear the words of their father – the original Israel, and the original children of Israel, the latter together and unified under an undisputed leader and sage. This atmosphere is heightened (and the potential discord averted) by the clever redistribution of allusions throughout the song. Rather than create or widen schisms between tribes, or alienate the tribes which were worthy of disapproval, the song’s author manages to simultaneously intensify the praise and cushion the blow (respectively) by a) purposely disassociating the allusions from the tribes to which they originally applied, and b) spreading those allusions throughout the text. The effect of the allusions is to be collectively referential of the entire episode of Jacob’s blessings – to evoke the feeling of all the children of Israel standing together, and cast that feeling, and those blessings, equally upon Deborah’s contemporary Benei Yisrael.

The blessings of Jacob are a prophetic poem about the tribal names, mixing praise and critique, bringing all the brothers together at a moment of balance and stability sandwiched between periods of familial hardship. Deborah the prophetess evokes its language as she sings her own poem about the same names, mixing praise and critique, trying to bring all the tribes together. She is invoking the most important moment of familial unity among the brothers who bore the tribal names. Deborah is a prophetess and a leader, but she’s something more as well – she is a mother. Jacob told his sons, “listen to [me,] Israel your father,” and Deborah exhorts the tribes as “Deborah, mother in Israel” – she is acting in the patriarch’s tradition and role. The significance of using the blessings of Jacob in her song is that Deborah is a leader who is also the national parent. Some of the children may deserve praise and others not, but they ultimately share a common fate, and must share the blessings they have in order for the family to thrive.

V. Conclusion

This article’s primary goal has been to make the case that the two passages under discussion share a common vocabulary not by happenstance, but due to intentional authorial effort. My interpretation of the textual overlaps and how they are distributed concludes that the Judges text uses the Genesis text as a source, and suggests that the author of Deborah’s song had good rhetorical cause to echo (and redistribute) the blessings of Jacob given the nature of the Deborah character and the challenges of her time.

When it comes to intertextuality without a clear “why,” there are always sure to be multiple ways to read the data. Perhaps someone has a different good idea as to why Judges 5 utilizes Genesis 49 in the way it does. Perhaps someone even has an interpretation that calls for reading Judges 5 as the source text and Genesis 49 as the derivative text. My hope is that this article serves as a catalyst for further study of the relationship between these texts, working from the premise that they are fundamentally intertextual. The overlaps invite everyone from rabbis to academics, from homileticists to historians, to see what else can be yielded in terms of literary and religious value.

[1] “The prevailing consensus is that this text dates as far back as the 11th or even 12th century BCE. That would… make Deborah’s Song one of the most ancient fragments of the Tanach (in fact, this is precisely how it is routinely described in popular literature and textbooks)…” Serge Frolov, “Dating Deborah,” https://www.thetorah.com/article/dating-deborah.

[2] In the interest of simplicity, “tribes” will be used to refer not only to the actual tribes as they were at the time of Deborah, but also to the men for whom those tribes are named (excepting Ephraim and Menashe, whose Genesis 49 counterpart is Joseph).

[3] “Regularity” and “variety” complement each other in this discussion. We do not merely see the same few Genesis 49 terms appear over and over in Judges 5, nor do we find a diverse set of Genesis 49 terms sparsely scattered. The allusions are quite varied, and they are found embedded throughout.

[4] NJB: “The princes of Issachar are with Deborah; Naphtali, with Barak, in the valley follows in hot pursuit.” BBE: “Your chiefs, Issachar, were with Deborah; and Naphtali was true to Barak; into the valley they went rushing out at his feet.”

[5] The word ברגליו might itself be somewhat of a Judah term; see the discussion of 5:27 in part III.

[6] Barnabas Lindars. Judges 1-5: A New Translation and Commentary (T&T Clark, 1995), 260.

[7] There are clear similarities between Judges 5:4-5 and Psalms 68:8-9 (Lindars, 229). This is not problematic, as I am not arguing for Genesis 49 as the only work intertextual with Judges 5; rather, just that Genesis 49 is the primary, and most important, source for the song of Deborah. There’s also no reason to suppose that the author of Psalm 68 couldn’t have been borrowing from Judges 5, or that both couldn’t have been utilizing an existing formula.

[8] יגור אניות is likely also meant to echo גור אריה from the blessing of Judah (Genesis 49:9).

[9] One could argue that the first overlapping term is actually שמעו in v.3, evoking ושמעו in Genesis 49:2. I consider this another data point in favor of intertextuality, but this data point is perhaps not so compelling when compared to the rest of the examples described, since shim’u, the imperative “listen” addressed to a plural audience, is a term we would expect to find introducing both of these passages even if they were totally unrelated. Similarly, שמים (heavens) (5:4, 5:20) may be expected after the rainstorm which the poem strongly implies should be read into chapter 4, but the term is also found in Joseph’s blessing, which is another data point. One might also suggest that אז לחם שערים, in 5:8, where לחם has the sense of war or battle, is an echo of Genesis 49:20, מאשר שמנה לחמו, where לחם means bread. Again, this data point is somewhat less compelling than others.

[10] Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar frames this form as archaic or stylized, implying that the nun could be a function of the era of composition or of poetic expression: “Less frequent, or only apparent terminations of the plur. masc. …] ־ין, as in Aramaic, found almost exclusively in the later books of the O.T. (apart from the poetical use in some of the older and even the oldest portions), viz. מלכין … צדנין … רצין … חטין … defectively אין … ימין. Cf. also מדין carpets, Ju 5, in the North-Palestinian song of Deborah, which also has other linguistic peculiarities” Wilhelm Gesenius, “Of the Plural,” Section 87, in Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar, (1813; ed. 1909 by E.F. Kautzsch; trans. 1910 by A.E. Cowley).

[11] There is a tradition (see Yevamot 103a), likely in part retrojected onto this episode from the Book of Judith, that sex or an offer of sex played a role in Yael’s plan to kill Sisera. The account in chapter 4 gives no hint of this; the textual basis is identified as Judges 5:27, with its references to sinking down and laying between her legs. This is a misguided reading. Eleven of the fourteen words in 5:27, including all of the suggestive ones, are borrowed from the blessings of Jacob – they are deployed here in service of allusion, not suggestiveness. The three unborrowed words are באשר, שם, and the relatively rare שדוד, which refers to Sisera being violently devastated or ruined. Sisera was fleeing a muddy battlefield on foot, in armor designed for fighting on a chariot that could haul all that weight around. He wouldn’t have had the energy for any sexual activities. He was desperate for a safe place to rest. We must note that the only rabbi named in connection with the sexual reading is R. Yohanan, who, later in the passage, also states that Eve and the serpent engaged in sexual intercourse in Eden. His assertion on that basis is startlingly similar to the Christian doctrine of “Original Sin.” In this passage, R. Yohanan leaves us a lot to unpack.

[12] If indeed the audience is meant to notice this echo, the case for shim’u/ve-shim’u (above, n9) as an echo becomes stronger on the strength of the proximity of ושמעו to ישראל אביכם.

[13] This period is the first chance in the narrative since the end of Genesis for tribal disunity to get ugly. Since then, at every point the nation was unified by something stronger than tribalism, whether it be the good times under Joseph’s care in Egypt, the bonds of slavery, the shared experience of a sudden miraculous escape, a shared revelation, mutually supportive travel in the wilderness, or a collaborative conquest of territory. Once all those uniting forces and causes dissolve, and each tribe claims a home turf, conflict can start to build and boil over.

[14] I date the events described in the song of Deborah to the period of 1250-1150 BCE. Verse 5:6 sets the scene with this evocative description: “In the days of Shamgar ben Anat, in the days of Yael, caravans ceased, and wayfarers went by roundabout paths.” This happens to be a very good concise description of the Late Bronze Age Collapse, a drawn-out series of downturns across the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Mediterranean that went on for several decades but accelerated in the 1170s BCE, give or take a few years (see for example Eric H. Cline, 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed [Princeton University Press, 2014, updated 2021]). A major trend during this period of decline was highways between major cities falling into disrepair, with merchant caravans unable to convey goods around the region, and individuals or groups of travelers having to hike roundabout trails through the wilderness to make their way from one population center to another.

The dating of the conquest of Hatzor and King Yavin presents some challenges. Scholars disagree on how to regard the Judges account vis-a-vis the similar account in Joshua 11. Did the Israelites conquer Hatzor twice, defeating two different Kings Yavin? Are these two accounts of one historical event? Does chapter 4 of Judges conflate some events recorded in Joshua with a later battle between Barak and Sisera? Is one or both of the accounts a pastiche of battle and conquest stories from over a period of time?

The “Late Bronze Age” section on the Wikipedia page “Tel Hazor” (as of February 2025) is a fascinating, balanced, and well-sourced sub-5-minute read. Most people do agree (regardless of their view on Tanakh as a reliable historical record) that in the decades surrounding 1200 BCE, Hatzor was catastrophically burned to the ground, and that the next people to build and settle there were Israelites of the early Iron Age. I believe that Judges 5:6 firmly places the events described in chapter 4 at the exact turn of the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

This assertion is bolstered by the narrative’s implication that Sisera had dominated militarily because he had access to iron chariots, since the period leading up to 1200 BCE is when smelted iron objects began to appear in Southern Anatolia and the Levant; in these regions, early iron smelting overlapped with the end of the Bronze Age. Sisera’s base was called חרושת הגוים, haroshet being a term for carving or engraving and other working of raw materials, which has been interpreted as “smithy” – in which case, Sisera would have had access to iron forging and fabrication at his military base before the technology for smelting iron was widespread.

Note that all this does not necessarily imply that the composition of the song itself is early – see, e.g., Prof. Serge Frolov’s “Dating Deborah” (above, n. 1), which argues for a much later (“Deuteronomistic”) date of composition. Frolov, as most, dates the events described to “the 12th or 11th centuries B.C.E.,” but I believe 5:6 points to the late 13th or early 12th. I make no claim as to the date of the song.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.