Dovid Campbell

The idea that the commandments of the Torah possess underlying rationales, ta’amei ha-mitzvot, was embraced by the Talmudic sages and subsequently complicated by the long history of Jewish thought.[1] If we survey this history, we find passionate debate regarding the origins and even the function of these rationales. Are they received through revelation, or are they discovered/invented through human inquiry? Are they a useful crutch for apologetics or an essential study for the committed Jew? This article will attempt to answer none of these questions.[2]

Instead, we will explore the subject of ta’amei ha-mitzvot through a question that some may find surprising, even offensive: Is it possible to properly fulfill a commandment without knowledge of these elusive te’amim? This will be a strictly legal exploration. Many have already articulated the importance of the spirit of Jewish law and its necessary integration with the letter.[3] But rarely, if ever, do we encounter a defense of ta’amei ha-mitzvot built upon a solid, halakhic foundation. For our purposes, that foundation will be the well-known principle of mitzvot tzerikhot kavvanah—that commandments require intention for their fulfillment.[4]

There is no obvious connection between this principle and the subject of ta’amei ha-mitzvot, an inconvenient fact that arguably dooms my project from the start. But, as I hope to show, such a connection was indeed developed by some of our greatest sages, and it is now possible to argue for the indispensability of ta’amei ha-mitzvot for satisfaction of the halakhic requirement of kavvanah. If this suggestion strikes you as surprising or farfetched, take comfort in this: I find it surprising too. And that surprise is only magnified by the fact that those rabbis who championed this view seemed to consider it painfully obvious.

My goal here is not to offer a practical halakhic conclusion. It is simply to throw light on an obscure halakhic subject that is as profound as it is mysterious. In exploring this subject, we are immediately challenged by some of the most difficult questions regarding the goals of the Torah, its commandments, and its vision for humanity. But we are also led to ponder much more subtle and personal questions about our daily practice as Jews, questions that chip away at the rust of rote ritual and spiritual indolence. Encouraging these types of questions, in whatever form they arise, is my goal for this article.

The Curious Case of the Three Commandments

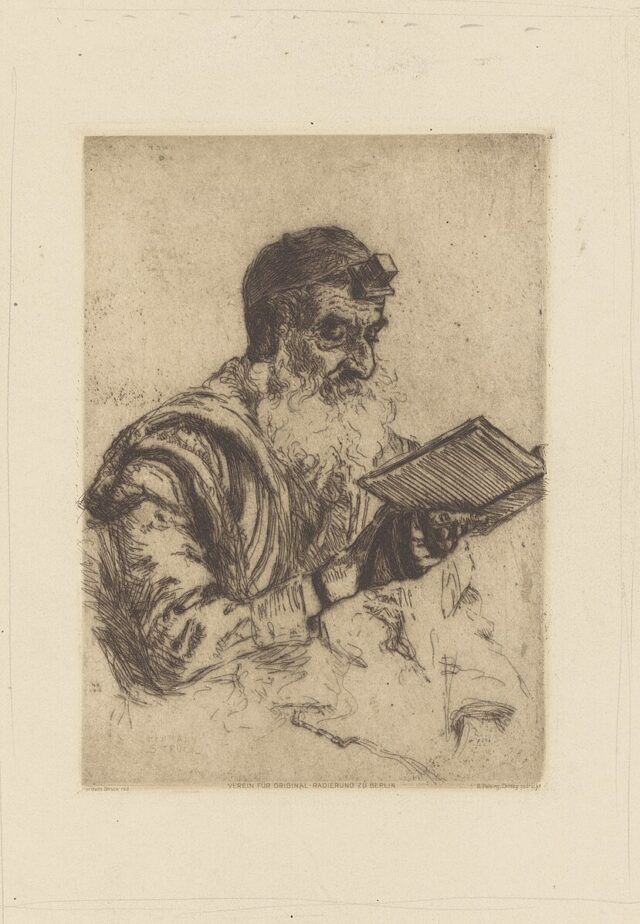

Tzitzit. Tefillin. Sukkah.

As R. Yoel Sirkis delved into the Arba’ah Turim, one of the primary works of medieval halakhah, he knew there must be something special about these three mitzvot. After all, the Arba’ah Turim, known as the Tur, had inexplicably highlighted them with a unique requirement—kavvanat ha-ta’am, the obligation to contemplate their underlying rationales at the time of their performance.[5] But why? The Tur gave no explanation.

R. Sirkis would eventually offer his own explanation in his Bayit Hadash, a major commentary on the Tur.[6] He had recognized that the biblical verses for these three commandments all shared a unique feature—they explicitly characterized their mitzvot as being “for the sake of” something beyond the mitzvah itself. For example, tzitzit are to be worn “for the sake of” remembering all of the commandments (Bamidbar 15:40). In R. Sirkis’ view, R. Ya’akov ben Asher, the author of the Tur, had understood these verses to be teaching the unique requirement of kavvanat ha-ta’am. Despite a lack of precedent and no clear Talmudic source, R. Sirkis emphatically asserted his position, and it has been incorporated into all major works of halakhah ever since.

Later works attempted to define the exact parameters of R. Sirkis’ position. Some claimed that contemplating these commandments’ rationales is ideal, but a lack of contemplation does not invalidate the mitzvah. Others insisted that such contemplation is absolutely necessary, and one must repeat the mitzvah if one failed to contemplate its ta’am.[7] Within this latter camp was R. Tzvi Elimelekh Spira of Dinov, an early Hasidic leader known by the name of his principal work, the Benei Yissaskhar. And while he agreed with R. Sirkis’ reasoning, he registered a major disagreement regarding its application. In his view, the Torah offers rationales for many more than three commandments.

A Rapidly-Expanding Project

Other rabbis had already suggested that R. Sirkis’ reasoning might be extended to mitzvot beyond tzitzit, tefillin, and sukkah. R. Yosef Te’omim in his Peri Megadim claimed that the verse commanding pidyon ha-ben, the redemption of the firstborn son, also presents a clear rationale.[8] If we accept the principle that a rationale recorded by the Torah indicates an obligation to contemplate it, it becomes difficult to limit this to the three mitzvot identified by the Tur. After all, doesn’t the Torah provide explanations, explicitly or implicitly, for many of its commandments?

This line of thought reached its apex in R. Spira’s Derekh Pikudekha, a work on the 613 commandments with special emphasis on ta’amei ha-mitzvot.[9] Unlike R. Sirkis, R. Spira did not believe that a verse must contain the term lema’an (“for the sake of”) in order to convey a ta’am. His reasoning was straightforward, if not entirely intuitive: Given that every mitzvah possesses innumerable te’amim, we must interpret any explicit mention of a ta’am as conveying a special obligation of kavvanah. With this foundation in place, R. Spira radically expanded the halakhic relevance of ta’amei ha-mitzvot.

For example, when teaching the mitzvah of procreation, the Torah writes, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the land” (Bereishit 1:28). R. Spira interprets this last clause, “fill the land,” as the ta’am of the preceding, and therefore requires that one performing the mitzvah have the intention to settle the land. In some cases, the connection seems even more distant. Regarding the commandment to sanctify the new moon, R. Spira speculates that it may be necessary to contemplate the purpose of the heavenly bodies, taught at the beginning of Bereishit—“and they shall be for signs and for festivals” (Bereishit 1:14). This example, and another that we will encounter later, suggest that R. Spira himself was still grappling with which factors should qualify a biblical verse as providing a bona fide ta’am.

The question of whether to embrace R. Spira’s expanded vision of kavvanat ha-ta’am remains open to the present day. R. Asher Weiss, in a work dedicated to general principles of mitzvah observance, argues that only the three mitzvot mentioned in the Tur require this special kavvanah. He rejects the many additions of R. Spira based on a novel distinction between a commandment’s rationale and its purpose, a distinction on which he unfortunately does not elaborate in this work.[10] By contrast, R. Zalman Nehemiah Goldberg cites R. Spira’s position in his own work on the halakhic implications of ta’amei ha-mitzvot and adduces further support for it from a passage in the Shulhan Arukh.[11]

Until now, our exploration of this subject has remained firmly within the theory of R. Sirkis, who sought a textual underpinning for the Tur’s ruling. Only the mention of a ta’am in the Torah itself could justify a requirement of kavvanat ha-ta’am. But if we revisit the pages of the Arba’ah Turim, we find an even older and more influential commentary standing opposite R. Sirkis’ Bayit Hadash—the Beit Yosef of R. Yosef Karo. And it is R. Karo’s two-word explanation of this halakhah that offers us our second lens on this mysterious and protracted debate.

Painfully Obvious

“Pashut hu.” It is obvious. This is all R. Karo finds necessary to write in explanation of the Tur’s revolutionary requirement of kavvanah for ta’amei ha-mitzvot.[12] And while this ruling may have been pashut to R. Karo, modern readers find themselves somewhat at a loss. Did R. Karo hold a text-based theory, similar to that of R. Sirkis or R. Spira, but simply feel it was too obvious to bother explaining? Or did he have a different theory altogether?

The Bei’ur Ha-Gra of R. Eliyahu Kramer, the legendary Vilna Gaon, provides sources for the rulings of the Shulhan Arukh, often with cryptic brevity. Regarding the obligation of kavvanat ha-ta’am for tzitzit, he cites Nedarim 62a, “Do things for the sake of their performance.”[13] He follows this with a warning to avoid the rebuke of Isaiah 29:13, “and their fear of Me has become a command of people, learned by rote.”[14] The Vilna Gaon seems to understand R. Karo’s ruling as a particular expression of a much more general Torah principle of mindful mitzvah observance.[15]

But why not simply follow the Bayit Hadash and cite the verse of tzitzit itself as the obvious source? Perhaps because R. Karo’s two-word explanation precludes it. R. Karo saw the Tur’s ruling as stemming from something so plain and obvious that no real explanation was necessary. R. Sirkis’ approach, with its clever discovery of discrete textual parallels between three specific mitzvot, simply could not be what R. Karo intended. The Bei’ur Ha-Gra therefore alerts us to the fact that there is an opposing theory of kavvanat ha-ta’am at work in the Shulhan Arukh.

For R. Karo, the self-evident requirement to perform mitzvot with sincere intention and to avoid rote ritual includes an obligation to contemplate the commandments’ underlying rationales. This understanding helps to explain the somewhat enigmatic rulings of later rabbis. R. Yehiel Mikhel Epstein, author of the influential Arukh Ha-Shulhan, writes in Orah Hayyim 25:8, “And know that even according to those halakhic decisors who hold that the commandments do not require intention, nevertheless it is certain that one must know the fundamental point of the commandment and its essence. And regarding tefillin, if one did not contemplate its meaning at all, he has not fulfilled the commandment, and it is simply like the act of a monkey.” For R. Epstein, the necessary kavvanah for tefillin is just a more stringent instance of a requirement that applies to all of the commandments.[16] This position is difficult to justify within the approach of R. Sirkis, who limits our obligation of kavvanat ha-ta’am to only three commandments, but it fits well within the approach of R. Karo.

Even more explicitly, R. Shaoul David Botschko writes in his Shulhan Arukh Kifshuto (Orah Hayyim 8:8), “In the fulfillment of the commandments, there are always two necessary intentions: The first, that the act be done to fulfill the command of the Creator, and the second, the unique meaning of this particular mitzvah.”[17] Once again, this generalized requirement to contemplate the rationale for any given commandment is difficult within the approach of R. Sirkis but fully aligned with our understanding of R. Karo. Later, in Orah Hayyim 25:5, R. Botschko explains that, although “in the majority of commandments, the author [R. Karo] does not bring their unique intention, in the commandment of tefillin, due to its great sanctity, the author wrote its unique intention” (emphasis added). R. Botschko sees the Shulhan Arukh’s incorporation of certain te’amim not as the result of discrete textual derivation, but as the application of a general principle that is sometimes taught explicitly.

We have explored two approaches to the obligation of kavvanat ha-ta’am: the textual theory of R. Sirkis and the more encompassing view of R. Karo. While both approaches seem to have left their mark on the halakhic process, it must be acknowledged that both share the quality of being unmoored from any concrete halakhic principle. R. Sirkis’ theory, however compelling, is ultimately speculative and unprecedented, and R. Karo’s view, however commonsensical, lacks clear definition and parameters. It might therefore be valuable to briefly explore a third approach to kavvanat ha-ta’am that, although radical, is grounded in an established principle.

R. Baruch Epstein was an influential Lithuanian rabbi and author, the son of R. Yehiel Mikhel Epstein, whom we met above. His work on Jewish prayer, Barukh She-Amar, contains a commentary on the Passover Haggadah, including a passage that has intrigued those interested in our subject.[18] Rabban Gamliel states that one who does not mention the three mitzvot of pesah, matzah, and maror at the Seder—including their rationales—has not fulfilled his obligation. Though some understand Rabban Gamliel to be referring to the obligation of recounting the Exodus from Egypt, others believe that his intention is the mitzvot of korban pesah, matzah, and maror themselves.[19] This provokes an important question: Since when must one articulate the ta’am of a mitzvah in order to fulfill it?

R. Epstein writes, “It is possible to explain that Rabban Gamliel holds, as is codified in Berakhot 13b, that mitzvot require kavvanah, and the idea of kavvanah is to intend their meaning. And he explains here what the meaning of these mitzvot is, and he expresses them in order,[20] and according to this, these mitzvot are not different from all other mitzvot, for one must intend the meanings of the mitzvot, and he therefore explains them.”

In R. Epstein’s view, Rabban Gamliel believes that kavvanat ha-ta’am is part and parcel of mitzvot tzerikhot kavvanah (mitzvot require intention), a concrete halakhic principle with substantial implications for the performance of any mitzvah. Though surprising and perhaps radical, R. Epstein’s explanation demonstrates the acute necessity of developing a robust theory of kavvanat ha-ta’am that incorporates the principle’s diverse manifestations, from the mitzvah of tzitzit to the Passover Seder.

A Renaissance of Ta’amei Ha-Mitzvot?

We have surveyed three approaches to unraveling the mystery of kavvanat ha-ta’am and unearthed new mysteries in the process. The source for this principle remains elusive, its application remains debated, and its core premise—the validity and discoverability of ta’amei ha-mitzvot—remains deeply contentious. One need only read Guide for the Perplexed 3:31 to realize that this discipline has been an object of major historical debate.

But even if we bracket the question of the validity and importance of these te’amim—and this is indeed reasonable given the strong Talmudic support—we are still left with the question of their discoverability. How can we ever know which rationale we are expected to contemplate for a given mitzvah? What determines an authoritative ta’am?

The textual approach of R. Sirkis and R. Spira would seem to offer us a solution, since we are only expected to contemplate what the verses already make explicit. But, as we have seen, R. Spira was not always certain about which verses represent clear-cut rationales. And, even when a rationale is clearly present, its precise meaning is often debatable. The verse commanding circumcision includes the apparent ta’am, “and it shall be for a sign of a covenant between Me and between you” (Genesis 17:11). R. Spira writes that the proper interpretation of this verse is found in the Sefer Ha-Hinnukh, who explains circumcision as a symbol of servitude to a master. However, R. Spira also embraces the explanation of R. Moshe Hagiz, who interprets it as a symbol of devotion between two loved ones. R. Spira ultimately obligates one to have both intentions in mind, indicating that even the process of interpreting an explicit, scriptural ta’am carries a challenging element of subjectivity.[21]

R. Hayyim Tyrer tackled this issue directly. Best known for his Be’eir Mayim Hayyim, a classic work of Hasidic exegesis, R. Tyrer was also an av beit din, head rabbinic judge, in multiple communities throughout Europe. His Sha’ar Ha-Tefillah, a work on Jewish prayer, includes a responsum that is directly relevant to our subject.[22]

Like some of the authorities we have seen, R. Tyrer believes that kavvanat ha-ta’am is “an obligation” in the performance of any mitzvah, and he adduces numerous Talmudic passages in support, including the statement of Rabban Gamliel above.[23] R. Tyrer acknowledges that this ruling may appear novel, but he insists that it is in fact explicit in R. Karo’s codification of most commandments in Orah Hayyim.[24] He then turns to the issue of subjectivity:

However, you should know that this matter is not set for him, and each person according to his own capacity, in reflecting upon the inner meanings and rationales for the commandments, based on the Torah as guided by the teachings of our sages … the intention that he knows and intends is also one aspect of His intention and will, may His Name be blessed, which He transmitted to us through Moses, His prophet and faithful servant. And [if] he does what he can to grasp and understand; this will be considered before His blessed Name as if he had intended, grasped, and understood in every necessary way, and thus his mitzvah is certainly accepted and pleasing before Him, blessed be He, and all according to the sincerity of his heart and the extent of his intention.

In other words, R. Tyrer acknowledges that ta’amei ha-mitzvot are endless, and no individual has a chance of comprehending them all. Nevertheless, if one earnestly investigates the rationale of a particular mitzvah, guided by the words of our sages, the ta’am he derives is certainly a true and acceptable kavvanah that fulfills his obligation. This approach is remarkably novel. While R. Spira argued that there is essentially an objective ta’am that one must strive to discover, R. Tyrer claims that our attempts to understand the underlying philosophies of the commandments are inherently exploratory and subjective. This reality is not a problem to be overcome, but rather a feature of the Torah’s boundless wisdom. And the fact that any sincerely derived rationale fulfills our obligation of kavvanat ha-ta’am serves as a source of encouragement in our personal efforts at discovery.

I began by noting that the aim of this article is not to suggest a practical halakhic stance. The issue is weighty, and the ramifications are vast. What I have hoped to show is that for a diverse and venerable collection of our great rabbis, the question of ta’amei ha-mitzvot was central—not due to a theoretical interest in an abstract philosophy of Judaism, but due to a deep conviction that daily practice must be imbued with a contemplation of the Torah’s goals and values. Whether we conclude that such contemplation is obligatory for all mitzvot or only three, this underlying conviction, this desire to enliven ritual through personal inquiry, is something to which we all aspire.

[1] See Sanhedrin 21b, Pesahim 119a, Bamidbar Rabbah 19:3.

[2] I would like to thank R. Adam Friedmann and R. Simi Lerner for their valuable comments on this article, and Lehrhaus editor Chesky Kopel for enhancing its style and presentation.

[3] In Guide for the Perplexed 3:51, Maimonides writes, “If we perform the commandments only with our limbs, we are like those who are engaged in digging in the ground, or hewing wood in the forest, without reflecting on the nature of those acts, or by whom they are commanded, or what is their object. We must not imagine that [in this way] we attain the highest perfection” (Friedlander translation). In the modern era, R. Samson Raphael Hirsch’s writings represent perhaps the most comprehensive and successful attempt to explore the spirit of Judaism through the lens of practical observance.

[4] Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 60:4, codifies that one must have the intention to fulfill a divine commandment at the time of its performance. See Mishnah Berurah, ad loc.

[5] Orah Hayyim 8 (tzitzit), 25 (tefillin), 625 (sukkah). Though the Tur does not state this explicitly regarding sukkah, R. Sirkis understands this to be its intention.

[6] Bayit Hadash to Orah Hayyim 8, s.v. “ve-nikra’im tzitzit,” and 625, s.v. “ba-sukkot teishevu.”

[7] See Peri Megadim, cited in Mishnah Berurah 25:15; Bikkurei Yaakov 625:3.

[8] Peri Megadim, Orah Hayyim, Mishbetzot Zahav 8:7.

[9] See Derekh Pikudekha, Introduction 1, section 5 (Lemberg, 1874).

[10] R. Asher Weiss, Minhat Asher: Kelalei Ha-Mitzvot (Makhon Minhat Asher, 2018), 176.

[11] R. Zalman Nehemiah Goldberg, Netiv Mitzvotekha (Makhon Mishpat Arukh, 2016), 46-47. R. Goldberg’s proof is from Orah Hayyim 187:3, where it is codified that if one fails to mention the concepts of circumcision and Torah in the “blessing of the Land” in birkat ha-mazon, he must repeat the blessing. Based on Rashi, Mishnah Berurah ad loc. explains that circumcision and Torah are the reasons for our inheritance of the Land of Israel.

[12] Beit Yosef, Orah Hayyim 8, s.v. “ve-ye-khavein be-hitatefo.” R. Karo does not explain the inclusion of rationales in Tur, Orah Hayyim 25 or 625.

[13] Translation follows R. Steinsaltz. Rashi ad loc. explains, “for the sake of Heaven.”

[14] My translation.

[15] R. Aharon Rubinfeld highlights this understanding when he notes that this Bei’ur Ha-Gra seems to disagree with R. Sirkis regarding the source for the requirement of kavvanat ha-ta’am. The verse in Isaiah is “a general principle to have intention in the performance of the commandments,” claims R. Rubinfeld, while R. Sirkis would explain that the source is to be found right in the verse commanding tzitzit itself. See his Torat Ha-Mitzvah (Jerusalem, 2016), 63.

[16] And one cannot claim that R. Sirkis’ approach is necessary to explain R. Epstein’s stringency here. Examining his treatment of the mitzvot of tzitzit and sukkah provides valuable context. In Orah Hayyim 8:13, R. Epstein indeed cites the requirement of kavvanat ha-ta’am for tzitzit, but there is no implication that one does not fulfill the mitzvah without this intention. It is the same with respect to sukkah in Orah Hayyim 625:5. R. Epstein’s stringency regarding kavvanah for tefillin is best explained by the contemplative purpose of tefillin itself.

[17] Kokhav Ya’akov, 2014. My translation.

[18] Bikkurei Yaakov 625:3, cited above, notes this passage as a source or parallel for his ruling concerning sukkah. See also the responsum of R. Hayyim Tyrer, cited below.

[19] See Abudarham; Orhot Hayyim; Rashbam (attributed), commentary to Haggadah, s.v. “Rabban Gamliel.”

[20] Or, “in the Seder.”

[21] Derekh Pikudekha, Mitzvah 2, Heilek Ha-Mahshavah, Section 3.

[22] R. Hayyim Tyrer, Sha’ar Ha-Tefillah (Warsaw, 1874), 3. Reprinted: Brooklyn, 1990.

[23] R. Tyrer’s other primary sources are the requirement that a divorce document be written with a special kavvanah for its purpose (see Even Ha-Ezer, Seder Ha-Get 55), and Zevahim 4:6, which teaches that an offering must be brought both for the sake of Hashem and for the sake of bringing Him satisfaction, the latter of which R. Tyrer interprets as kavvanat ha-ta’am.

[24] Somewhat strangely, R. Tyrer only gives the examples of tefillin and tzitzit, commandments that even the minimalist position of R. Sirkis would acknowledge. However, we have already seen that R. Goldberg identified this principle in the laws of birkat ha-mazon as well, and the Shulhan Arukh’s treatment of mitzvot such as Shema, prayer, Shabbat, and the various holidays includes passages that may arguably be considered to present the kavvanat ha-ta’am.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.