Chesky Kopel

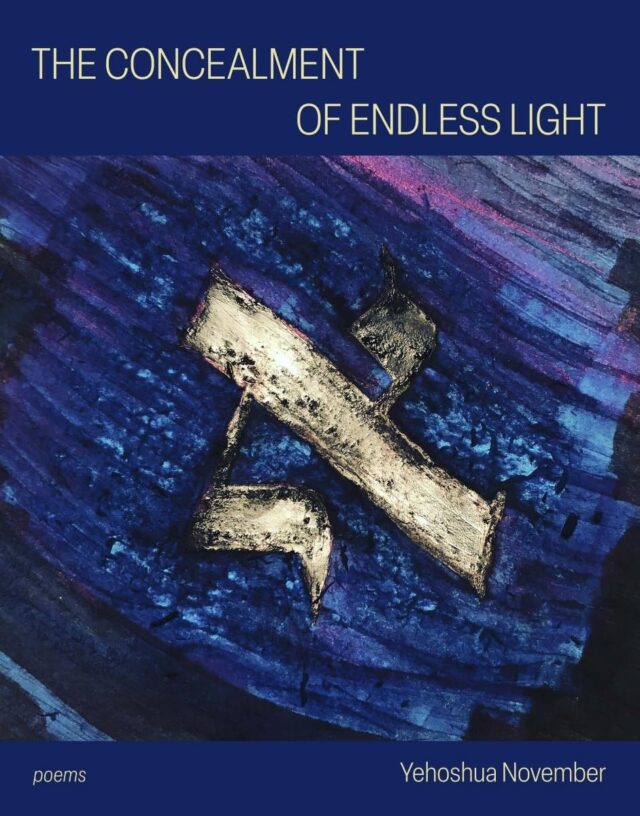

Review of Yehoshua November, The Concealment of Endless Light (Orison Books, 2024).

Yehoshua November’s latest collection of poetry is concerned with the nature of the human soul and its relationship to the human body. Across 32 poems, The Concealment of Endless Light engages repeatedly with the mystery of the soul, exploring alternate realities, each of which paradoxically retains its truth in the face of the others. The resulting words are beautiful, often tinged with nostalgia and regret, and are of great utility to the Jews of 5785 who, in the face of a frightening and unstable world, may seek to turn inward, to understand themselves and their relationship with God.

In the theology of the Tanya, which November invokes in his work, the soul inhabiting the human body is tethered to the name of God:

Like a rope, the mystics say.

The bottom strands, the soul in a body.

The top braids, the source of the soul fastened to Heaven’s rafters. Tug

at either end

and the other moves.

Slightly.[1]

This soul-rope metaphor is explicated in Tanya, Iggeret Ha-Teshuvah 4-5, as an interpretation of Vayikra 32:9: “For God’s portion [heilek Hashem] is this people; Ya’akov, God’s own allotment [hevel nahalato].” According to the Tanya, the human soul is no less than a portion of God’s essence–an alternative translation of heilek Hashem–and that portion is attached to God via a rope–an alternative translation for hevel–in a manner that enables the holder of either end to influence the other. November gives this traditional Chabad image memorable expression in a new literary language and a visually creative arrangement of text, illustrating the rope in its constant state of motion.

But what makes November’s poetry so compelling is his ability to weave traditional images like this one together with the products of his own powerful imagination. Alongside the rope, November offers additional images, describing the soul in the body as “a ball chain tied // to the source of the soul– // the light bulb’s toggle switch,” or as “captain of a nearly sinking ship, / the rudders outmoded, / the porthole fogged.”[2] This diverse collection of differing metaphors reflects the poet’s process of discovering and rediscovering the same theological elements, but in different worldly manifestations. In this spectrum of truths, even the traditional assumptions of order and divine providence are destabilized: “Like one descending / the stairs to the supply room / for a paperclip / but pausing / beneath the door frame, / a soul enters / a particular body / and cannot / remember why.”[3]

As it seeks to define the soul, The Concealment of Endless Light also sees the soul everywhere: animating the sanitation workers who perform their own sacred work outside the open window of the shul;[4] reflected in the koi fish which dart around a pond “like flashes of clarity”;[5] and even, most provocatively, tormenting an old Nazi in Newark who can no longer quiet his conscience (“a drunken former S.S. officer / follows the spiritual leader down Union Street, / begging for Divine exoneration. / ‘I will not forgive you,’ / the rabbi answers, each time.”).[6]

The specter of Nazis returns in contemporary form in “There is Only One Story,” a poem subtitled “on the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting” (59). November, who earned his MFA at the University of Pittsburgh and spent the early years of his marriage in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood where Tree of Life is located, is uniquely well-positioned to deliver this lamentation. (Indeed, Squirrel Hill, too, reappears elsewhere in the collection.[7]) In a 1966 interview, the Yiddish poet Yankev Glatshteyn was asked by his colleague Abraham Tabachnik to define the role of Yiddish poets. Glatshteyn replied that Yiddish poets bore a responsibility to the world to record the unimaginable pain of the Holocaust: “The Yiddish poet must be the aesthetic recorder of the story of all that happened, and he must preserve this so that the words stand the test of time.”[8] November bears this responsibility admirably in the aftermath of the 2018 massacre at the Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh–a calamity that, given its geographic and political context, calls not for a Yiddish poet but instead one fluent in the anxious English of a minority group in twenty-first century America.

In this English-language rendering of timeless Jewish tragedy, “There is Only One Story,” the shooter is welcomed by a loving community: “A stranger passes through / unlocked double doors. / Blocks away, Robert’s son / begins his bar mitzvah portion: / Abraham inviting angels, wayfarers, / into his open tent.” Like the Jews of Pittsburgh, Abraham was soon in mourning: “And Abraham came to eulogize over Sarah / and to cry for her. / And according to the hidden story– / the one mystics tell– / Abraham represents the soul / and Sarah the body.”[9] The speaker of the poem once again orients his thoughts around the fraught relationship of soul and body, suggesting quite radically that the souls of the murdered Jews remain part of their community, and join the community in mourning their own bodies: “Eleven souls / ascend to the region of mystery / then swoop down to hover, / incandescently, over their former lives.”

The soul/body theme also illuminates November’s choice of language throughout. It may seem odd–or at least conspicuous–that this body of poetry, so steeped in the ideas of hasidut and the trappings of Jewish life, often renders Jewish terms in English: “Genesis” for “Bereishit,” “quorum” for “minyan,” “blessing” for “berakhah,” “Sabbath” for “Shabbat,” and so on. This stylistic choice partly serves a practical aim, allowing November to expand his readership beyond the bounds of the literary shtetl. It also places the poems in a specific cultural context, purchasing admission into the broader canon of American poetry. But the word choices should also be understood on their own spiritual terms, revealing sanctity in the language spoken by Jews in this latter-day Bavel, bringing the soul down into the bodily husk of our galut vernacular.

Observant Jews in America tend to mean different things when they speak of “books” and when they speak of “sefarim,” although the former is a direct translation of the latter. Sefarim, works of Torah scholarship, are understood to be a proper arena for serving God, while books are not. This gap is readily bridged in November’s English verse, without any need for a constructed doctrine of Torah U-Madda. Here, “books” comprise a world infused with divinity. A poem titled “Faith” (48) provides a glimpse:

To climb each rung

of the mind,

teeter

at the top,

and then surrender

like a librarian who reaches for a book

on the highest shelf

and then breathes in

the strange and foreign air

above the ladder.

For November, as for our forefather Jacob, thoughts of faith in God conjure a ladder “of the mind.” Here, the ladder is placed in the context of library stacks of the mind, in which the attainer of faith is reaching for a “book” and encounters there (perhaps unexpectedly) a feeling of devotion that seems “strange and foreign” in the book-ish atmosphere. “Faith” sketches not just the idea, but the experience of encountering God in our lower world.

Indeed, as with all poets, November is at his best when his insights are shown rather than told. In another example, November shows how devotion to God and fealty to science exist on different planes and resist attempts at reconciliation: “Indeed, the Law of the Conservation of Matter // would disappear from every textbook / were it not announced again and again // over Heaven’s staticky intercom.”[10] There is a clear conflict between the principle of physics that mass is neither created nor destroyed and the kabbalistic principle that the world’s continued existence depends on the constant issuance of God’s creative “speech.”[11] November’s poem does not seek to resolve the paradox directly, but to portray the simultaneous truth of both realities, casting the laws of physics, along with everything else in existence, as subject to the mystery of Creation.[12] Only very occasionally do November’s poems do too much of the readers’ work, spelling out that “what He was thinking / is history’s great mystery,”[13] or protesting that the Jew is regarded as a “Stereotype of opulence, comfort, / while, simultaneously, the name / behind history’s agitated isms?”[14]

Many reviews of November’s earlier poetry collections have addressed the novelty of his identity as a hasidic Jew in the community of poets.[15] In doing so, they seem to ask the question ‘what sort of poet is the observant Jew?’ This may be an interesting question for some readers, but for this reviewer, and in this context, the far more interesting question is its converse: what sort of observant Jew is the poet? November addressed this question directly in a recent essay in these virtual pages: “poets are Purim Jews. Their tendency not to mention the Divine or the exalted moment, but to insist on underlying meaning and wonder in the mundane, appears to go beyond agnosticism.”

This “Purim” orientation is clear in The Concealment of Endless Light, and we are all fortunate for that. But if poets are Purim Jews, then what kind of Jews are poetry readers–those of us who, like this reviewer, appreciate and interpret this written medium, but are hopeless to contribute to it ourselves? In a recent poetry textbook, Michelle Bonczek Evory proposes that:

Unlike a person speaking, who can use the entire body to gesture, poetry has only a voice to rely on to speak. Yet the poem seeks to speak to a reader as if it had a body. The poem uses rhythm, pauses, stresses, inflections, and different speeds to engage the listener’s body. As readers, it is our role to listen to the speaker of the poem and to embody the words the speaker speaks with our own self as if we are the ones who’ve spoken.[16]

Just as the body requires a soul, the soul requires a body; poets produce a soul of meaning that must seek and find its body, the readers. May we all rise to that challenge.

In The Concealment of Endless Light, a collection so enthralled by the soul, the body receives the last word, and so the same pertains in this review. The final poem, “Notes on Marriage” (77-81) refers to the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s analogy of Abraham/Sarah to soul/body, which we had already seen above in “There is Only One Story,” but adds a complication: “If Sarah represents the body / and Abraham the soul, / why did God tell Abraham / to listen to Sarah’s voice? / Because, the mystics answer, / in the Messianic Era, / we will see that the source of the body / is loftier than the source of the soul, / and so a soul descends into a body.”[17]

[1] “The Fragment of the Soul in the Body” (68).

[2] “The Fragment of the Soul in the Body” (68). Perhaps unsurprisingly, The Concealment of Endless Light is not November’s first attempt to devise poetic metaphors for the point of convergence between divinity and humanity. Eight years ago, another poem described the soul in the body as “like an old Russian immigrant / looking out his apartment’s only window…All correspondence / has been forwarded to this address. / But I am not from here. I am not from here at all.” “The Soul in a Body,” The Sun (August 2016).

[3] “Notes on the Soul” (1).

[4] “Morning Prayer and the Waste Management Co.” (64-65).

[5] “The Visit” (62).

[6] “Teachers and Students” (8).

[7] See “What About the Here and Now?” (43) (“When I was twenty-four, / I felt a great weight lift / as I walked past New Life Dry Cleaners, / Squirrel Hill snowmelt underfoot, / and first believed / in the Baal Shem Tov’s conception / of Divine Providence.”)

[8] The quote here reflects my translation of Dr. Yael Levy’s unpublished Hebrew translation of the original Yiddish, featured in a YouTube lecture here.

[9] The collection’s “Notes” section (82) credits this conceptualization to “the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Likkutei Sichos, Volume 1, page 31.”

[10] “Re-creation Ex Nihilo Via Divine Utterance” (27).

[11] See Tanya, Likutei Amarim 21.

[12] Occasionally, November appears to use his experience of contradictions as a sort of absurdist comic relief. See “The Deed” (40): “I grade expository essays on the overlap / between Buddhism and psychology / to pay for my children’s cheder tuition.”

[13] “Women at Prayer” (67).

[14] “Universal Symbol” (49).

[15] See, e.g., Rivka Krause, “REVIEW: Two Worlds Exist,” Tradition Online (March 27, 2023); David Nilsen, “Two Worlds Exist by Yehoshua November,” The Rumpus (February 17, 2017); Robert Hirschfield, “God ‘Beneath the Ordinary’,” Sojourners (January 2014); Eve Grubin, “Hope in November,” The Jewish Daily Forward (January 26, 2011).

[16] Michelle Bonczek Evory, Naming the Unnameable: An Approach to Poetry for New Generations (Open SUNY, 2018), at Ch. 2.

[17] As with “There is Only One Story” (see note 13 above), the “Notes” credit this analysis to “Likkutei Sichos, Volume 1, pages 33-34.”

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.