Yisroel Ben-Porat

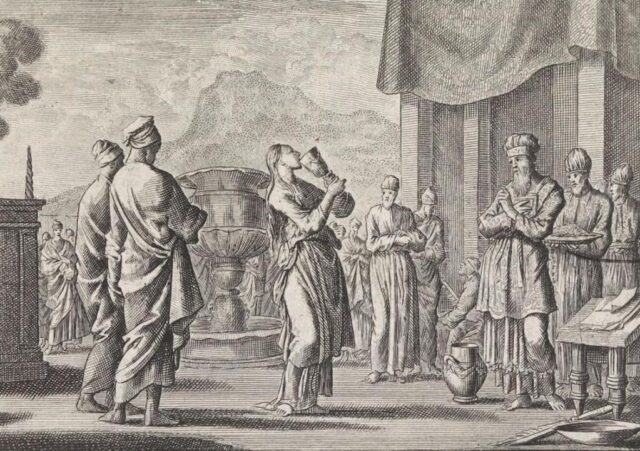

Much ink has been spilled on the Jewish view of abortion. This essay explores an obscure set of sources that have received little attention in the literature. My purpose in this article is not to take a halakhic or philosophical stance on the status of fetal life, but rather to shed light on some neglected rabbinic texts relevant to this issue. Tractate Sotah (the “wayward wife”) elaborates on the miraculous biblical ritual (Numbers 5:11-31) for testing the fidelity of a suspected adulteress. The Sotah drinks bitter water mixed with dirt, and a priest erases into it a scroll containing God’s name. In the rabbinic view, if she is guilty, she dies, but if she is innocent, she will be blessed with children. A dispute between Rashi and Tosafot regarding the case of a pregnant Sotah addresses the ethics of performing a ritual potentially fatal for a fetus.

The locus classicus of this case, Sotah 26a, discusses which women are eligible to undergo the Sotah ritual. There, a baraita rules that a woman “pregnant from [the husband] himself either drinks [the bitter water] or forfeits her ketubah.” According to Rashi, whose reading seems to be the most straightforward interpretation, this passage permits a pregnant Sotah to drink the bitter water, despite the fatal potential for the fetus.[1] Tosafot, by contrast, reject Rashi’s read, instead explaining that when the baraita says the pregnant Sotah may drink the bitter water, it means she may undergo the ritual only after she gives birth. It is possible that this dispute revolves around the status of fetal life, which may have broader implications regarding the issue of abortion in Jewish law; however, theories elucidated in later commentaries complicate the ethical implications of the pregnant Sotah and undermine its relevance to abortion.

Rashi and Tosafot

Rashi’s position, as reflected in his brief and ambiguous comment on the baraita in Sotah 26a, indicates that he does not consider abortion to be murder, which appears to inform his approach to the case of the pregnant Sotah. Tosafot’s interpretation, on the other hand, suggests a more restrictive view of abortion. Both texts require careful analysis to identify the precise point of contention.

Rashi seems to read the baraita in Sotah 26a as indicating a lack of concern for fetal life, which is perhaps its most straightforward interpretation. Rashi comments, “We do not say that the child should not be killed.”[2] This double negative implies that causing the death of a pregnant Sotah would not be considered feticide (murder of the fetus). Accordingly, the mitzvah (biblical commandment) of performing the Sotah ritual[3] outweighs the value of ensuring the fetus carries to term; conversely, if abortion is feticide, it would be difficult to understand why the mitzvah of Sotah would outweigh the prohibition of murder, which is yehareg ve-al ya’avor (categorically inviolable). However, the implications of this position beyond the context of Sotah remain unclear from this source alone. It does not necessarily follow from here that Rashi would allow an abortion in cases that do not have the mitigating factor of fulfilling a mitzvah; and as I will demonstrate below, many sources identify Sotah as a unique exception to general rules about abortion.

To better understand the reasoning behind Rashi’s assumption that abortion is not feticide, we must consider another relevant source, which appears outside the context of Sotah in Arakhin 7a. There, the Mishnah states, “A woman who is taken to be executed, we do not wait until she gives birth. A woman in the throes of labor, we wait until she gives birth.” By allowing the execution of a pregnant woman, the Mishnah does not seem concerned by the death it will inevitably cause to the fetus. The Gemara initially characterizes the first ruling as “obvious” given that the fetus is “her body.” Subsequently, the Gemara suggests that one might have thought to delay the execution based on Exodus 21:22, which indicates that the fetus is the “property of the husband” (i.e., a separate entity from the mother).[4] As to why the Mishnah did not accept that argument, R. Yohanan cites a scriptural source, interpreting “and they shall also both of them die” (Deuteronomy 22:22)—the mandate of capital punishment for adultery—to include both a mother and her fetus.

Rashi’s statement on Sotah seems consistent with his approach to Arakhin 7a. Commenting on the Mishnah there, he explains, “We kill her fetus with her, since it is one body.” Rashi implies that the fetus is considered part of the mother’s body (ubar yerekh imo), and thus the execution of a pregnant woman does not amount to feticide.[5] Here, too, however, one cannot necessarily extrapolate broader leniency for abortion beyond the context of capital punishment, which also fulfills a biblical commandment. Nevertheless, Rashi seems to apply the logic of Arakhin 7a to Sotah 26a, suggesting the existence of at least two Talmudic rulings that appear to disregard the value of preserving fetal life.

Tosafot, however, reject Rashi’s read of the baraita in Sotah 26a, insisting that the passage should be interpreted to allow a pregnant Sotah to undergo the ritual only after giving birth. They challenge, “Why let it be killed? Why would we care [to rush the ritual]? Let us wait until she gives birth.”[6] The rhetoric of Tosafot implies that they take issue with Rashi’s read for its apparent lack of care for the life of the fetus. Granted, performing the ritual fulfills a mitzvah, yet it is possible to do so without endangering the fetus by simply waiting until the mother gives birth before drinking the bitter water. But this reading of Sotah 26a seems to conflict with the implication of Arakhin 7a, which emphasizes the need for an urgent execution. Tosafot therefore distinguish between Sotah and capital punishment: R. Yohanan’s derivation for executing a pregnant woman in Arakhin 7a implies that absent a gezeirat ha-katuv (inscrutable Scriptural commandment), the rational approach is to refrain from causing the death of a fetus, “because it is the husband’s property” (i.e., a separate entity from the mother). Thus, since no such exegesis exists regarding Sotah, delaying the ritual is warranted.[7]

In Arakhin, Tosafot elaborate an argument that bolsters distinguishing between Arakhin 7a and Sotah 26a. They explain that after gemar din (conviction), the reason for not delaying execution stems from the concern of inui ha-din (affliction of judgment), the psychological agony of remaining on death row.[8] The analogue of gemar din in the context of Sotah is not clear, but the factor of inui ha-din would not seem to apply here. Although performing the Sotah ritual fulfills a mitzvah, it remains optional; the wife is not forced to undergo it, and either spouse has the power to cancel it before God’s name is erased.[9] Not only is there no rush to complete the process, but the judges intentionally delay it and attempt to convince the woman to confess instead.[10] It follows that a pregnant Sotah may not undergo the ritual before she gives birth, since doing so may unnecessarily kill the fetus. Thus, whereas Rashi seems to view Sotah as analogous to Arakhin 7a, Tosafot view R. Yohanan’s teaching in Arakhin 7a as exceptional to dinei nefashot (capital cases), rather than the basis for potentially allowing one to cause the death of the fetus in the case of a pregnant Sotah.

The commentary of Meiri potentially provides support for Rashi’s reading of the baraita in Sotah by analogizing Sotah to capital punishment. Unlike Tosafot, Meiri maintains that the baraita in Sotah 26a allows a pregnant woman to undergo the ritual during her pregnancy and does not require a delay on account of the fetus. He explains that if the Sotah is innocent, there is no concern, and if she is guilty, she does not deserve a delay any more than she would in dinei nefashot, and he invokes the ruling in Arakhin 7a that we execute a pregnant woman.[11] Evidently, Meiri sees the potential outcome of death to the Sotah as analogous to capital punishment, which thus explains why he does not require a delay in the case of a pregnant Sotah. This conceptual framework supports Rashi’s read, which assumed that the pregnant Sotah has the same rule as Arakhin 7a. Tosafot, by contrast, implicitly reject the conceptualization of Sotah as an analogous capital case, instead noting that Arakhin’s harsh ruling is the result of scriptural exegesis that does not apply to Sotah.

There is conflicting evidence in the Talmud regarding the place of Sotah in Jewish law. On one hand, Meiri’s view analogizing Sotah to dinei nefashot has support from several sources. Firstly, the Sotah appears before the High Court of seventy-one judges in Jerusalem, typically reserved for grave cases of national significance. There, “we threaten her like the way we threaten witnesses in capital cases,” an analogy that Meiri interprets as referring to procedures similar to those prescribed in Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5, which includes questioning, “inquiry and interrogation” (derishah ve-hakirah), and emphasizing the gravity of shedding innocent blood; in the context of Sotah, the judges similarly warn the wife that the bitter water is lethal and she should not jeopardize her life.[12] Additionally, another source derives from the Sotah ritual that deliberations in capital cases must first proceed with arguments for acquittal.[13] These sources provide a compelling basis for Meiri’s analogy.[14]

Some sources, on the other hand, support Tosafot and undermine the analogy between Sotah and capital punishment. As Ramban emphasizes, the miraculous intervention is sui generis in Halakhah. Sotah uniquely weaves divine judgment into the framework of human law.[15] Ultimately, if the Sotah dies from the ritual, it is not an execution in the conventional sense. Although the Sotah travels to the High Court, Tosafot do not view this step as dispositive for fulfilling the ritual.[16] Additionally, capital punishment requires two witnesses of the offense, a criterion definitionally absent in the case of the Sotah. Although the ritual is initiated on the basis of two witnesses who verified the husband’s kinui (formal warning) and the wife’s subsequent setirah (suspicious act of seclusion), the Sotah is only eligible for the ritual if there are no witnesses for the act of adultery itself.[17] Perhaps due to these sources, Tosafot concluded that the analogy between Sotah and capital punishment remains incomplete beyond the specific procedural rules invoked by the Talmud.

Regardless of the question of how to conceptualize the legal nature of the Sotah ritual, a fundamental dispute seems to emerge between Rashi and Tosafot on the status of fetal life. Rashi appears to assume that abortion is not murder, whereas Tosafot implies that it is. Such a conclusion is bolstered by the fact that Rashi does not appear to contend with Tosafot’s ethical challenge to not unnecessarily endanger the fetus. His lack of insistence on delaying the ritual might lead one to infer a broader position that takes the rejection of fetal personhood to a very lenient conclusion. However, as I explore below, later thinkers offer novel explanations of Rashi’s position that undermine such claims.

Modern Perspectives

Within Rashi’s school of thought that allows the testing of a pregnant Sotah, postmedieval rabbinic commentaries provide new arguments that complicate the ethical implications of the ritual. Some suggest that the divine nature of the Sotah ritual absolves us of moral responsibility for the potential feticide, either because God will delay the Sotah’s death to protect the fetus, or because we are not responsible for God’s judgment. Other more recent thinkers offer a radical theory that the Sotah is presumed to be innocent, thus negating the risk of death for the fetus.

Whereas Meiri conceptualized the Sotah ritual as dinei nefashot, thereby locating it within the jurisdiction of human (Jewish) law, some offer a different conceptualization that considers the divine element. A letter from R. Joseph Rosen (the Rogatchover Gaon) to R. Elhanan Halpern discusses the possibility that a fatal outcome of the Sotah ritual would fall under the category of mitah be-yedei shamayim (“death at the hands of heaven”).[18] If God determines the fate of the Sotah, one could also suggest that God determines the fate of the pregnant Sotah’s fetus, absolving the court of responsibility. R. Elazar Moshe Horowitz takes this idea in one direction, pointing out that God can choose to temporarily suspend the effects of the bitter water to protect the fetus: “Everything is in the hands of heaven, and by His will He can delay her [death] for some time.”[19] In this read, we are not morally responsible because the fetus may very well live. More recently, some have sought to avoid R. Horowitz’s implication that the presence of a fetus could undermine the efficacy of the Sotah ritual and cause the woman to live when she otherwise should have died. Instead, these thinkers suggest that if the bitter water kills the woman, we are not morally responsible for a divine action; it is not our place to question or speculate why God would allow the death of the fetus.[20] Either way, according to this school of thought, the ethics of the pregnant Sotah are subordinated to inscrutable divine judgment, much like the execution of a pregnant woman, which R. Yohanan ultimately justifies through a gezeirat ha-katuv. Those who emphasize the role of divine intervention here cannot conclusively extrapolate broader implications for abortion from the case of the pregnant Sotah.

Another crucial distinction between Sotah 26a and Arakhin 7a is the possibility of innocence. In the latter case, the court has already convicted the pregnant woman, and the execution will inevitably cause the death of the fetus. The Sotah’s guilt, however, is definitionally doubtful, and she may survive the ritual. At most, the ritual presents a risk of death, which is mitigated by a variety of caveats that can render the test ineffective. According to rabbinic law, the bitter water will not be fatal if the husband himself ever committed a sexual sin; if witnesses to the adultery are overseas and did not come forward; if the husband knows she is guilty; and according to several opinions, if she had merit protecting her, the effect could be delayed for a significant amount of time, which would enable the pregnancy to come to term safely.[21] It would be impossible for anyone to know with certainty that all the conditions of efficacy have been met. Thus, enabling a pregnant Sotah to undergo the ritual is not conceptually analogous to a direct act of abortion.

Some take this argument even further by suggesting that the Sotah who chooses to undergo the ritual is assumed to be innocent. In this view, a pregnant Sotah would pose no risk to the fetus. As mentioned above, the Sotah ritual is optional for the woman. R. Yehiel Michel Epstein (Arukh Ha-Shulhan) suggests that the Sotah’s innocence is “close to certain” because she chooses to undergo the ritual; presumably, a woman who knows her own guilt would refuse the ritual for fear of death.[22] Similarly, R. Yaakov Kamenetsky suggests that the purpose of the Sotah ritual is not to punish adultery but rather to prove the wife’s innocence, since the husband’s jealousy and doubt will not be assuaged without divine intervention. As evidence, he cites the Gemara’s comment that by allowing God’s name to be erased into the Sotah waters, the Torah demonstrates the importance of peace between husband and wife; the goal to restore marital harmony, he implies, can only be achieved if the wife remains alive.[23] Other sources, however, suggest a more punitive purpose; at various stages throughout the process, the judges humiliate the Sotah and immensely pressure her to confess.[24] Arguably, though, even if one accepts the punitive view, a woman who nevertheless insists on proceeding with the ritual would very likely be innocent. Accordingly, it would follow that a pregnant Sotah would almost never pose a risk to the fetus, thus limiting the relevance of the case to the issue of abortion.

Conclusion

Some understandings of the pregnant Sotah potentially intersect with the issue of abortion. A straightforward reading of the dispute between Rashi and Tosafot revolves around the status of fetal life. Rashi seems to maintain that the fetus is considered part of the mother’s body; thus, just as we execute a pregnant woman, we allow a pregnant Sotah to undergo the ritual. Tosafot, by contrast, seem to reject this possibility based on a concern for the life of the fetus, and they understand the case where a pregnant mother receives capital punishment as the exception to the rule against abortion. However, the broader implications of Rashi’s position remain inconclusive. One postmedieval school of thought conceptualizes Sotah as a unique divine punishment, which undermines its relevance to the issue of abortion. Similarly, a group of modern thinkers reinterpret Sotah as a presumptively non-fatal ritual which would present no risk to the fetus, again limiting the relevance of the case to abortion.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we must still contend with Arakhin 7a. While there is disagreement about the case of the pregnant Sotah and whether it is analogous to capital punishment, all sources seem to agree that we execute a pregnant woman despite the inevitable abortion it entails. Whereas the implications of Sotah 26a remain inconclusive, given its atypical place in Jewish law, Arakhin 7a seems directly relevant to the issue of abortion. Yet, because it has received attention in the literature, a full analysis of Arakhin 7a falls beyond the scope of this essay, which focuses on the case of the pregnant Sotah.[25] Further research is necessary to determine how the positions of Rashi, Tosafot, and other commentaries on Sotah 26a and Arakhin 7a might fit with their approaches to additional sources relevant to abortion in rabbinic literature. Despite its obscurity, the intellectual history of the pregnant Sotah offers a rich case study with significant implications for Jewish thought.

[1] An aggadic source implies that the purpose of the Sotah ritual is to determine the paternity of a pregnant woman’s fetus; see Tanhuma [Buber ed.], Naso 5; Lisa Grushcow, Writing the Wayward Wife: Rabbinic Interpretations of Sotah (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 103. The baraita also records a dispute between R. Meir and the Rabbis whether a woman pregnant from a previous husband is eligible for the Sotah ritual initiated by her current husband. Cf. Sotah 24a; Tosefta Sotah 5:1-2; Mishneh Le-Melekh, Hilkhot Sotah 2:7; Avi Gurman, The Origins and Evolution of the Prohibition Forbidding the Remarriage of the Pregnant or Nursing Widow in Jewish Law [Heb.] (Jerusalem: Karmel, 2020), 169-188. However, Sifrei Zuta cites a dissenting view of Rabban Gamliel that, unlike the baraita, excludes a pregnant Sotah from the ritual; see Keren Orah, Sotah 26a; Hazon Yehezkel, Tosefta Sotah 5:1; Sapirei Efraim, Sifrei Zuta 5:28.

[2] Sotah 26a, s.v. o shotot. Similarly, Rambam glosses that a pregnant Sotah undergoes the ritual “as she is [now]” (Hilkhot Sotah 2:7); for commentary on Rambam’s position, see R. Sheraga Faivel Shternfeld, Sefer Parashat Sotah (Bnei Brak, 5782), 146-149. See also Meiri, discussed below in this essay.

[3] See, e.g., Rambam, Sefer Ha-Mitzvot, Positive Commandments 223, and the introductory heading in print editions of Rambam’s Hilkhot Sotah; Sefer Ha-Hinukh 365; Sefer Mitzvot Gadol, Positive Commandments 56.

[4] Cf. Bava Kamma 49a.

[5] Arakhin 7a, s.v. ha-ishah; cf. Rabbeinu Gershom ad. loc; Ran al ha-Rif (19a) to Hullin 58a (first explanation); Tosafot R. A. Eiger, Arakhin 1:4; R. Y. S. Elyashiv, He’arot be-Masekhet Sotah, 26a and He’arot be-Masekhet Bava Kamma, 49a; Dvar Shaul, Sotah §45.

[6] Sotah 26a, s.v. me’uberet atzmo.

[7] See Mishneh Le-Melekh, Hilkhot Sotah 2:7; Beit Shmuel, Even Ha-Ezer 11; Torat Ha-Kenaot, Sotah 26a; R. Y. S. Elyashiv, He’arot Be-Masekhet Sotah, 26a; Netivot Ha-Kodesh, Sotah 26a; Netziv, Meromei Sadeh, Sotah 26a.

[8] Arakhin 7a, s.v. yashvah; cf. Tosafot, Sanhedrin 80b s.v. ubar; Ran al ha-Rif (19a) to Hullin 58a (second explanation). The author/editor/compiler of Tosafot printed in the Vilna edition of the Talmud may differ across tractates, and thus we should not necessarily assume consistency between the passages discussed here, or other discussions of Tosafot elsewhere about abortion.

[9] Sotah 6a, 20a. See Tosafot, Sotah 7b, s.v. mah and 17b, s.v. mah.

[10] Sotah 7a-7b; see also Torat Ha-Kenaot, Sotah 26a.

[11] Sotah 26a, s.v. kinei.

[12] Sotah 7a, Meiri ad. loc; see also Rashi ad. loc; cf. Tiferet Yisrael, Sotah 1:4; Ishay Rosen-Zvi, The Mishnaic Sotah Ritual: Temple, Gender and Midrash (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 49-66.

[13] Sanhedrin 33a; cf. Sifrei Bamidbar 12. See also Tosafot, Sotah 17b, s.v. mah.

[14] For halakhic discussions, see Minhat Sotah, Sotah 26a; Tosafot R. A. Eiger, Mishnah Yevamot 6:1; Shu”t R. A Eiger, Responsa, vol. I, 222:18; Shu”t Hatam Sofer, Hoshen Mishpat 77.

[15] Ramban al ha-Torah, Numbers 5:20.

[17] See, e.g., Sotah 2a-2b, 31a.

[18] Shu”t Tzofnat Paneah 212. Cf. Tzofnat Paneah al Masekhtot Sotah Gittin (Mehon Ha-Maor ed., 2016), pp. 7-8.

[19] Ohel Moshe, vol. I, Sotah 26a; see also Netivot Ha-Kodesh, Sotah 26a (citing an oral teaching of R. Yisrael Meir Kagan [Hafetz Hayyim]). Cf. Radal, Sotah 20b.

[20] See Sefat Emet, Sotah 26a; R. Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, He’arot be-Masakhet Sotah 26a; and Alei Ba’er ibid.

[21] Sotah 47b, 6a-6b, 20a-21a, 22b; Sifrei Bamidbar 7-8. Cf. Tosefta Sotah 2:4; Yerushalmi Sotah 3:5; Rambam, Hilkhot Sotah 3:20; Radal, Sotah 20b; Netivot Ha-Kodesh, Sotah 26a.

[22] Arukh Ha-Shulhan, Even Ha-Ezer 178; see also Minhah Hareivah, Sotah 26a.

[23] Emet Le-Yaakov, Numbers 5:15; Hullin 141a; for further discussion, see Yosef Lindell, “Was the Sotah Meant to be Innocent?” (Lehrhaus, 6/9/22). See also Alei Ba’er, Sotah 26a, n. 103.

[24] Sotah 7a-7b, 14a; Rambam, Hilkhot Sotah 3:3; cf. Guide to the Perplexed III:49; Rosen-Tzvi, Mishnaic Sotah Ritual, 3.

[25] For discussion, see, e.g., R. J. David Bleich, “Abortion in Halakhic Literature,” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 10, no. 2 (1968): 72-120; R. Eliezer Melamed, Simhat Ha-Bayit U-Birkhato 9:3, n. 4.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.