Yisroel Ben-Porat

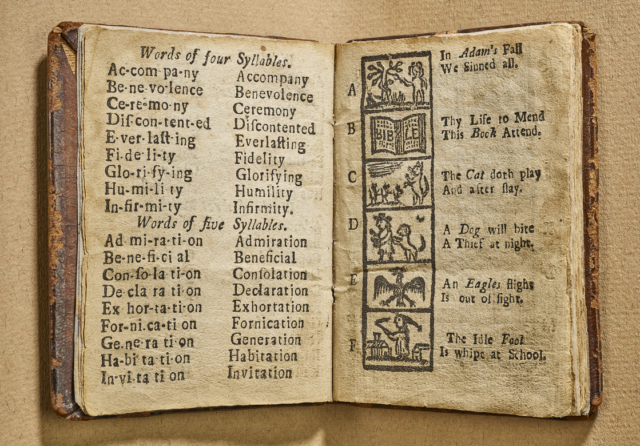

“In Adam’s fall we sinned all,” read generations of schoolchildren learning the alphabet in colonial New England. The story of Adam and Eve has received considerable commentary over the past few millennia. The biblical account defies easy interpretation, contains manifold ambiguities, and raises serious theological questions. For both Jews and Christians, the primordial sin reflects deeper themes about the past, present, and future of humanity. Historically, misogyny has cast a long shadow over Jewish and Christian interpretations, which tend to emphasize Eve’s erroneous behavior. Yet a close reading and comparative analysis of a midrash on Adam’s role in the narrative sheds new light on the primordial sin. These novel interpretations shift the blame and reinterpret the narrative in unexpected ways that offer the modern reader surprisingly relevant moral teachings about sexuality.

Serpentine Strategy

In the biblical account, the Serpent initiated a conversation with Eve and convinced her to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. Eve then “took of its fruit and ate. She also gave some to her husband [with her (as it is written in Hebrew, ‘imah’)], and he ate.”[1] Most commentators, such as Rashi and Ibn Ezra, assume that Eve first conversed with the Serpent alone before eating the forbidden fruit and feeding it to Adam.[2] This assumption raises a natural question: if Adam was not present during the Serpent’s conversation with Eve, where was he, or what was he doing at that time?[3]

A neglected midrash helps fill this gap in the biblical narrative:

“The woman replied to the serpent” (Genesis 3:2) – and where was Adam at that moment? Aba bar Koryah said: he was involved in derekh eretz [sex (lit. “the way of the world”)] and was sleeping.

The Rabbis said: The Holy One, Blessed Be He, took him around the whole entire world [and] said to him: here is a place for planting, here is a place for seeding. This is what is written: “A land no man had traversed, / Where no human being (adam)had dwelt” (Jeremiah 2:6) – [meaning that] Adam, the first [man], had not dwelt there.[4]

Here, Aba bar Koryah and the Rabbis respectively offer two explanations for Adam’s absence: either Adam went to sleep after having sex with Eve, or God took him on a world tour. Before analyzing these divergent opinions, we must first consider the opening scriptural citation and its relationship to the framing question. Yefeh To’ar asks why Eve’s reply to the Serpent, rather than the Serpent’s initial statement to her, prompts the query about Adam’s location. His answer implicitly reflects a misogynistic assumption: were Adam present in the previous verse, the Serpent conceivably would have talked to her rather than Adam, but it would not have been appropriate for Eve to reply before her husband. More fundamentally, he assumes that Adam would not have remained silent in the face of her destructive reply.[5]

The latter explanation offers a more compelling basis for the midrash. Had Adam been present, he presumably would have corrected Eve’s erroneous reply that God forbade even touching the Tree of Knowledge, since he knew that God had only mentioned eating.[6] As a result, the Serpent intentionally approached Eve, knowing that he could not deceive Adam. Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer provides an alternative, misogynistic strategy for the Serpent: Adam will ignore him because Man is stubborn, whereas Woman is susceptible to influence.[7] These approaches provide an important interpretive framework for the literary necessity of Adam’s absence.

Prelapsarian Procreation

While the Serpent may have waited for the perfect moment to approach Eve, Aba bar Koryah’s depiction of prelapsarian sex merits closer attention. This opinion accords with the position of R. Yehoshua ben Karha, who explains the juxtaposition of Adam and Eve’s nakedness (arumim) with the Serpent’s shrewdness (arum) by suggesting that the latter desired Eve after seeing her having sex with Adam.[8] Thus, Aba bar Koryah’s suggestion reflects the tendency of Midrash to fill gaps in biblical chronology. Here, he seamlessly weaves together the events into a logical sequence.

From a theological standpoint, the chronology of sex preceding the primordial sin raises larger questions about the rabbinic attitude toward sexuality.[9] Some sources suggest that the figurative earthiness of sex awakened humanity to worldly temptations, ultimately leading to sin.[10] However, one could also argue that placing sex before the existence of evil implies that sex is not inherently sinful, but rather merely a function of the natural order. It is tempting to read Aba bar Koryah’s euphemism derekh eretz (“the way of the world”) as a straightforward depiction of prelapsarian innocence.[11]

While Aba bar Koryah’s view remains ambiguous, other interpretations of the primordial sin suggest a more negative attitude toward sexuality. R. Yehoshua ben Karha refers to the “sin (hatayah) from which the Evil One jumped upon them, since he saw them involved in derekh eretz [sex], and he desired her.” By describing prelapsarian sex as sinful, he implies that the act is inherently associated with evil.[12] Along similar lines, Arizal argues that Adam failed by not waiting until the holier time of Friday evening to procreate with Eve, thus prioritizing his physical needs over spirituality.[13] The Talmud also connects illicit sexuality to the primordial sin by casting Eve and the Serpent as adulterers.[14] According to these sources, sex itself constituted the primordial sin.

A different midrash emphasizes the public nature of Adam and Eve’s intercourse, suggesting yet another possible dimension. An unattributed opinion states that “no creature procreated before Adam, the first [man]. ‘He knew’ is not written here, but rather ‘Now the man knew (yada) his wife Eve’ (Genesis 4:1) – he demonstrated (hodi’a) derekh eretz to all [creatures].”[15] Indeed, the Talmud castigates the idea of having sex outside or in the presence of animals.[16] Yet rather than criticizing Adam, the midrash merely depicts the idyllic innocence prior to the primordial sin. Even Adam’s experimental bestiality before meeting Eve escaped rabbinic ire.[17] Because the Evil Inclination did not yet exist, they had no shame from nakedness nor, it stands to reason, from sexual activity.[18] As R. Aharon Lichtenstein noted, modern emphasis on the holiness of marital sexuality contrasts with largely negative earlier views. Yet contemporary rereadings of the primordial sin can cohere with the more ambiguous rabbinic legacy as reflected in the above sources.

Adam Asleep

A charitable reading of prelapsarian sex must also contend with the significance of Adam’s subsequent sleep during Eve’s encounter with the Serpent. The sleep motif alludes to the creation of Eve, when “God cast a deep sleep upon the man.”[19] Implicitly, perhaps, Aba bar Koryah suggests that the primordial sin represents a new stage of Creation.[20] Additionally, the Talmud describes sleep as one-sixtieth of death, so it serves as a fitting foreshadow for the end of immortality.[21] Thus, the imagery here engages meaningfully with deeper themes embedded in the biblical text.

Another cryptic source fleshes out the theological significance of Adam’s sleep. Commenting on “the record of Adam’s line,” Tanhuma relates that during Adam’s sleep, God showed him the righteous people throughout the generations from Noah through Solomon. Subsequently, Adam awoke, whereupon God told him, “‘Did you see them? [I swear] by your life, all these righteous ones come from you.’ Once He told him this, his spirit calmed.”[22] It is unclear whether Tanhuma refers to Adam’s first sleep before Eve or perhaps a subsequent slumber after the primordial sin. The opening scriptural citation, as well as the emphasis on future righteousness calming Adam’s spirit, alludes to the psychological agony of an earlier failure.[23]

Beyond the rich thematic resonances of Adam’s sleep, it is worth exploring Eve’s behavior in Aba bar Koryah’s approach. Etz Yosef offers yet another misogynistic read, blaming Eve for not waiting for Adam to awaken (or, according to the Rabbis, to return from his world tour with God).[24] Yet Yirmiyahu Stavisky points to a more compelling interpretation that will likely resonate with modern readers. Adam, after fulfilling his sexual needs, abandoned Eve by going to sleep instead of keeping her company, thus leaving her vulnerable to seduction by the Serpent. He likens Adam’s behavior to a husband who spends too much time at the office and neglects to pay adequate attention to his wife. The biblical text, he argues, implicitly reflects this emotional distance by having God interrogate Adam and Eve separately.[25]

Modern halakhic literature on proper sexual conduct supports a critical read of Adam’s behavior. R. Eliezer Melamed, drawing upon a Talmudic analogy to a rooster, cautions that “after marital sexual relations [hibbur (lit. “connection”)], a man should not act like those husbands who lose interest in their wives, turn their backs, and fall asleep.”[26] Echoing rabbinic emphasis on female sexual pleasure, this idea urges men to overcome their natural postcoital tiredness and remain awake to please their wives.[27] According to Aba bar Koryah, Adam seems to have failed in this regard. Thus, he, rather than Eve, takes primary responsibility for the primordial sin.

Divine World Tour

The theme of sex might also inform the second approach in the midrash regarding Adam’s absence. This opinion, attributed to the unnamed Rabbis, suggests that while the Serpent spoke to Eve, God took Adam around the world, showing him places to plant and settle civilization. Like Aba bar Koryah, the Rabbis allude to an earlier theme in creation: Adam’s world-building role of naming all the creatures.[28] While they differ from Aba bar Koryah’s explanation for Adam’s absence, the Rabbis might nevertheless agree with his chronology of a prelapsarian procreation. If so, it would fittingly follow that Adam begins considering the process of determining the future location of humanity.[29] Similarly, the Rabbis’ emphasis on earthiness echoes Aba bar Koryah’s euphemism of derekh eretz, perhaps also suggesting that over-involvement with the physical world inevitably leads to sin.[30]

However, a nuanced difference in the formulation of the two approaches may have significance. Whereas Aba bar Koryah explains Adam’s absence through the latter’s own agency, the Rabbis specify that God took Adam around the world. One might conclude that the latter approach, unlike the former, implicitly shifts the blame away from Adam by providing an alibi. Yet the divine world tour does not necessarily exculpate Adam. Unlike R. Hiyya, who criticizes Eve for expanding God’s prohibition,[31] Avot de-Rabbi Natan (1:5) blames Adam for miscommunicating to Eve that God prohibited touching. R. Yehuda Henkin explains that God designed Eve as Adam’s intellectual equal (ezer ke-negdo) to help him fulfill the commandment not to eat from the tree. Unfortunately, Adam viewed Eve as inferior, miscommunicating the scope of the prohibition to include touching, and neglecting even to tell her the name of the tree – hence her oblique reference to “the tree in the middle of the garden.” As a result of this disrespect, we still suffer the consequences of gender inequality.[32] Building on this insight, R. Aryeh Klapper suggests that God enabled the Serpent to converse with Eve alone to test whether Adam could share Revelation with her; by keeping Torah to himself, Adam failed.

This reading can apply to both explanations in the midrash for Adam’s absence. For Aba bar Koryah and the Rabbis respectively, God engineered the episode either by commanding Adam to procreate, which caused him to fall asleep, or taking him on a world-building mission, which actively removed him from the Garden. Furthermore, this interpretation could apply to the biblical text itself; whatever the reason for Adam’s absence, it is clearly a necessary literary feature in the narrative. How the midrash fills this gap seems to shift the blame toward Adam rather than Eve, while yielding important theological implications on the nature of sexuality.

Conclusion

We began this essay with the exegetical issue of Adam’s absence. We then analyzed two approaches in a midrash from Genesis Rabbah: Aba bar Koryah’s suggestion of Adam’s sleeping after sex, and the Rabbis’ placing him on a divine world tour. Our reading of the midrash seriously undermines a misogynistic interpretation of the primordial sin and should give pause to those who dismissively blame Eve for our imperfect world. While one can read Aba bar Koryah as suggesting that sex is inevitably sinful, a more compelling read leads to the conclusion that sex is inherently a neutral force, but that Adam’s sleeping afterward should be viewed as an act of neglect. Similarly, one can read the Rabbis’ approach as indicting, rather than exculpating, Adam’s responsibility for the primordial sin. To repair our fractured world, men must take these lessons to heart by respecting women’s inner world and treating them as intellectual equals. If misogyny caused our first falling, then reversing Adam’s error is a crucial step toward building a better future.

[1] Genesis 3:6. All biblical translations are from Sefaria. All other translations are my own.

[2] According to Rashi, the prepositional phrase imah indicates their proximity only when Eve fed Adam. Alternatively, Ibn Ezra reads imah as an adverbial modifier indicating that Adam and Eve ate together. Interestingly, Ibn Ezra emphasizes the shared responsibility for the primordial sin, noting that Adam did not sin unintentionally. He elaborates that after eating from the Tree of “Knowledge,” Adam euphemistically “knew” Eve (Genesis 4:1), connecting the onset of libidinal impulse to nascent moral understanding. In John Milton’s retelling, Eve convinces Adam to fulfill their labors more adequately by working separately (Paradise Lost, bk. IX, ll. 205-225).

[3] Lekah Tov (to Genesis 3:1) offers the most straightforward approach, simply pointing to the only other ongoing activity the Bible had prescribed for Adam: “The LORD God took the man and placed him in the garden of Eden, to till it and tend it [le-avdah u-le-shamrah]” (Genesis 2:15), i.e., the responsibility to preserve Eden’s ecological welfare. From a peshat perspective, agriculture provides an easy explanation for Adam’s earlier absence. Nevertheless, we may still ask from a literary standpoint what function Adam’s absence plays in the narrative.

Interestingly, Midrash Tanhuma Bereshit 8:3 implicitly rejects the premise of our question by describing Adam as present in the conversation; cf. the parallel version in Genesis Rabbah 19:4, cited by Rashi and Shemirat Ha-Lashon II:9:6. The textual basis for Adam’s presence remains tenuous. The plural conjugations and pronouns in the conversation might indicate an audience of two for the Serpent. However, it seems more likely that the language merely includes Adam in an abstract rather than concrete sense. God’s criticizing Adam for listening to Eve’s voice (Genesis 3:17) might refer to her reply to the Serpent, but it more likely alludes to her efforts to convince Adam to eat left unstated in the text (see Genesis Rabbah 19:5; 20:8).

John Gill’s eighteenth-century Exposition of the Old Testament notes a reading of imah in Genesis 3:6 as “who was with her,” thereby temporally extending Adam’s proximity throughout the conversation: “The Jews infer from hence, that Adam was with her all the while, and heard the discourse between the serpent and her, yet did not interpose nor dissuade his wife from eating the fruit.” I am not aware of any such source in Jewish tradition. In his sixteenth-century Bible commentary, John Calvin records this interpretation without attribution and dismisses it.

[5] Yefeh To’ar ad loc.; this notion echoes the comment of Netziv that Eve ate alone first, because had Adam been present, he would not have let the incident occur considering his “closeness with God” (Ha’amek Davar, Genesis 3:6).

[6] Genesis 2:17, 3:3. See also Avot de-Rabbi Natan 1:5, discussed below in this essay.

[7] Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer 13. See also Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed 2:30, which emphasizes the connection between the Serpent and Eve.

[8] Genesis 2:25-3:1; Genesis Rabbah 18:6; Yefeh To’ar ad loc. 19:3.

[9] This chronology accords with Sanhedrin 38b, despite Genesis 4:1 implying that sex occurred afterward, unless the verses appear out of chronological order. For a comparison of ancient Jewish and early Christian views on the possibility of sex in the Garden, see Gary Anderson, “Celibacy or Consummation in the Garden? Reflections on Early Jewish and Christian Interpretations of the Garden of Eden,” Harvard Theological Review 82, no. 2 (1989): 121-148.

[10] Rashi to Ecclesiastes 7:29, based on Ecclesiastes Rabbah (ad loc.), suggests that the sexual union of Adam and Eve resulted in the emergence of sin. See also Eshed Ha-Nehalim, Genesis Rabbah 19:3, and this lecture. The euphemism derekh eretz (see, e.g., Eruvin 100b) contrasts with more clinical terms such as tashmish (“usage”), bi’ah (“entering”), or hibbur (“connection”).

[11] In this sense, the term refers to proper conduct; see, e.g., Derekh Eretz Rabbah 5:2. For a discussion of the term derekh eretz, see R. Eliezer Melamed, Simhat Ha-Bayit U-Birkhato 2:4.

[12] Genesis Rabbah 18:6. However, Yedei Moshe (ad loc.) notes that Rashi’s citation of this midrash contains the word eitzah (idea) rather than hatayah (sin), suggesting that the correct text reads etyah (pen or plan, e.g., Bava Batra 17a). Maharzu (ad loc.) posits that the midrash uses the term “sin” anachronistically.

[13] Sha’ar Ha-Gilgulim 29:2. One could read this idea into the statement of R. Eleazar criticizing Adam and Eve for not “waiting in their tranquility” (himtinu be-shalvatan) even six hours (Genesis Rabbah 18:6; see Yefeh To’ar and Nezer Ha-Kodesh ad loc. for analysis of the hourly chronology). [Regarding intimacy on Shabbat in early Judaism, see Malka Simkovich’s article here.] See also B’nei Yissaschar, (Yod’ei Binah ed.), Ma’amarei Hodesh Nissan 8 (pp. 603-604, n. 46), which offers a similar perspective glossing Yerushalmi Pesahim 10:1.

[14] See, e.g., Sotah 9b; Shabbat 146a; Zohar 1:28b.

[15] Genesis Rabbah 22:2; for a critical perspective, see Matnot Kehunah ad loc. 18:6 and Ya’arot Devash 9.

[16] Sanhedrin 46a; Niddah 16b-17a.

[17] Yevamot 63a; see Rashi, Genesis 2:23 s.v. zot ha-pa’am; Hizkuni ad loc.; Vikuah Rabbeinu Yehiel Mi-Pariz, p. 29.

[18] Genesis 2:25; Maharzu, Genesis Rabbah 18:6.

[19] Genesis 2:21; That slumber emphasizes Adam’s vulnerability as a human; R. Hoshaya remarks that God put Adam to sleep to prevent the angels from erroneously worshiping him as a deity (Genesis Rabbah 8:10).

[20] Cf. Genesis Rabbah 18:4, which discusses a prototype creation of Eve that Adam rejected.

[21] Berakhot 57b. Sex, too, connects to death; as psychotherapist Irv Yalom explains, it “is the great death-neutralizer, the absolute vital antithesis of death… The French term for orgasm, la petite mort (‘little death’), signifies the orgasmic loss of the self”; Irvin D. Yalom, The Gift of Therapy: An Open Letter to a New Generation of Therapists and Their Patients (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 131. For a mussar lesson connecting this midrash to another Talmudic discussion of sleep, see Hokhmat Ha-Matzpun, vol. I, ma’amar 95 (pp. 153-154).

[22] Genesis 5:1; Midrash Tanhuma Bereshit, Buber ed., 32. In a parallel Talmudic version, which does not mention sleep, God shows Adam all generations of Torah scholars until they reach R. Akiva, whose erudition and suffering simultaneously gladdens and saddens Adam (Sanhedrin 38b).

[23] Cf. the anxiety recorded in Avodah Zarah 8a. On the other hand, the verses may appear out of chronological order.

[24] Etz Yosef, Genesis Rabbah 19:3.

[26] Eruvin 100b; Peninei Halakhah, Simhat Ha-Bayit U-Birkhato 2:2-4 (quotation p. 28).

[27] See, e.g., Pesahim 49b; Midrash Rabbah Ha-Mevu’ar (I:19:3) notes the conflation of sex and sleep in Nazir 23b (glossing Judges 5:27).

[29] See, however, Nezer Ha-Kodesh (Genesis Rabbah 19:3), who aligns Aba bar Koryah with R. Yehoshua ben Karha and the Rabbis with a dissenting opinion that rejects the notion of prelapsarian sex (ibid 18:6).

[30] See Eshed Ha-Nehalim, Genesis Rabbah 19:3, as well as this lecture.

[31] “[Genesis 3:3] … This is what is written, “Do not add to His words, / Lest He indict you and you be proved a liar” (Proverbs 30:6). Rabbi Hiyya taught that you may not make the fence more than the principal thing, so that it will not fall and cut the plants” (Genesis Rabbah 19:3 [4 in some editions]).

[32] Genesis 2:18-19, 3:3; Yehuda Henkin, Mehalakhim Be-Mikra (Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2019), 23-26. An earlier and more concise version appears in B’nei Banim, vol. 4, ma’amar 12 (pp. 120-121); for an English version, see Yehuda Henkin, Equality Lost: Essays in Torah Commentary, Halacha, and Jewish Thought (Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 1999), 12-20.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.