Shlomo Zuckier

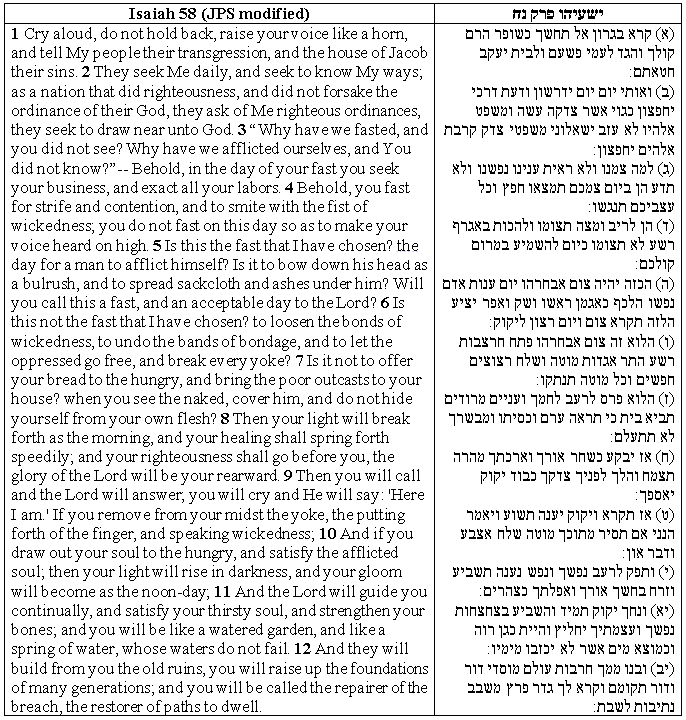

What is Yom Kippur about? Reflexively, many of us would say “fasting,” in the sense of refraining from eating and drink. But the haftara read on Yom Kippur, taken from Isaiah 58, gives a radically different conception of what a fast day should be, focusing on matters other than refraining from eating. This essay will take a close look at the literary artistry of Isaiah, trying to discern its literary-theological message, and considering what this tells us about fasting and Yom Kippur in general.

The charge to fast on Yom Kippur stems from the biblical phrase תענו את נפשותיכם (Lev. 16:29), usually translated as “you shall afflict/debase yourselves” but probably better construed as “you shall deny your gullet.”[1] This phrase, cited several times in the Torah and clearly associated with Yom Kippur, will be the key to decoding the literary message of Isaiah 58.

Isaiah 58 comes to correct the people’s severe misimpression of fast days. They saw the technical observance of the fast, namely debasing oneself and abstaining from eating, as the be all and end all of its observance. While meticulously following the ritual technicalities of fasting, they were oppressing their workers – even having them work on the fast itself! – and they failed to assist those less fortunate.

For Isaiah, however, the fast must be directed towards helping others. One is to practice self-debasement precisely in order to support others. We see this in the multiple cases of inversion that the chapter offers to the phrase ענוי נפש (self-affliction), which function on both a literary and a thematic level. The passage is uniquely constructed so as to complicate the standard understanding of mortification of flesh that people generally associate with Yom Kippur.

– Rather than affliction (ענוי), the people are bidden to do the opposite: they are to feed the hungry (v. 7; הלוא פרס לרעב לחמך), and satiate the gullet (v. 11; והשביע בצחצחות נפשך). In fact, there is a charge precisely to satiate those souls that are afflicted (v. 10; ונפש נענה תשביע), the exact opposite of תענו את נפשותיכם!

– Not only is the opposite of ענוי called for, but the root עני itself is redirected, as well: by punning on the root for affliction (ענוי) the text shows that it cannot be simply followed as it sounds. The poor (עני) are mentioned, but they are to be brought in (v. 7; עניים מרודים תביא בית). If one acts properly, God will respond (v. 9; אז תקרא וה’ יענה), clearly a pun replacing affliction (יְעַנֶּה) with divine response (יַעֲנֶה).

– Additionally, the word נפש (soul/person/gullet) is redirected in various manners. Instead of denying themselves/their gullet, the people are expected to “give themselves,” i.e. their compassion, to the hungry (v. 10; ותפק לרעב נפשך), and satiate the gullet of the oppressed (v. 10; ונפש נענה תשביע), such that God will in turn satiate their gullet (v. 11; והשביע בצחצחות נפשך). The soul needs to be sated rather than oppressed.

The literary assault on עינוי נפש thus includes the deployment of antonyms to affliction as well as the use of both the root ע.נ.י and the noun נפש to promote the opposite of affliction – supporting the poor is what will cause God to respond.

These linguistic inversions are accompanied by several thematic inversions, as well. It is clear that the standard understanding of a fast, as understood by Isaiah’s addresses, was to not eat or drink (see vv. 3 and 5), to wear sackcloth (v. 5) and to bow one’s head and ignore one’s flesh (v. 5). These practices correlate to the additional ענויים (Yom Kippur observances) familiar from the Talmud and contemporary practice – one neither eats nor drinks, afflicts one’s flesh by neither washing nor applying oil, refrains from sexual activity, and practices sartorial debasement by not wearing shoes.

Yet Isaiah’s account of the fast required by God inverts each of these themes:

– Isaiah charges the people to eat and drink and be healthy, the opposite of the prohibitions against eating and drinking. Specifically, the people are told to feed the poor and downtrodden, to reverse their affliction.

– The people are charged to clothe the poor, inverting the concept of mourning by wearing sackcloth and/or not wearing shoes.

– The nation is urged “do not forsake your flesh,” which clearly opposes a conception of carnal debasement. However, there is another inversion at work. This verse is understood, in various Second Temple and Rabbinic traditions, as relating to a scenario where a man would marry his niece in order to support her financially.[2] This is another counterweight to the prohibition against carnal activity for the fast day, as one is urged to consider undertaking a sexual relationship for the purpose of assisting someone in an unfortunate financial position.

The key to reading this critique is the overturning and re-directing of the fast day, accomplished through punning and re-deployment of the phrase ענוי נפש that is paradigmatic of fast days, and especially Yom Kippur.

A true fast, one God desires, will inspire those fasting to utilize the self-abnegation for the purpose of caring for those less fortunate than themselves. The failure of the people was that their fast was accompanied by doing business, and doing so on the back of others (vv. 3-4; הן ביום צמכם תמצאו חפץ, הן לריב ומצה תצומו). In doing so, they doubly missed the point – they were not truly denying themselves, and they certainly were not helping others. A successful fast, says Isaiah, must – either by reallocation of resources (v. 7; פרס לרעב לחמך) – or a reassignment of sympathies (v. 10; ותפק לרעב נפשך) – redirect one’s attention from preoccupation with one’s self (נפש) to concern for others. In the long run, he promises, the self-affliction (ענוי) leads to God listening (ה’ יענה), and leads to ultimate self-fulfillment (והשביע בצחצחות נפשך).

Whether by redirecting food not eaten to a food pantry or becoming inspired through fasting to identify with those who are starving, Isaiah’s message – equally important now as then – is that we ensure that the practices of Yom Kippur reinforce our awareness of those less fortunate and our capacity to support them. Failing to do so would mean that we have become so self-absorbed in our own affliction that we missed its point entirely.

May we all merit to internalize Isaiah’s rebuke, and to fulfill the fast with its full significance!

[1] The word נפש is cognate of the Akkadian nappisu, which means throat. In the context of debasement, it seems to use the word נפש as a metonym for consumption.

[2] Aharon Shemesh has treated this matter in various places. See his “Scriptural Interpretations in the Damascus Document and their Parallels in Rabbinic Midrash,” in The Damascus Document: A Centennial of Discovery, ed. J. Baumgarten (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 163-167, which cites CD 6:21-7:1, CD 8:4-8, and Yevamot 62b.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.