Ari Lamm

Editors’ Note: This month, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks turns 70 years old. In honor of this occasion we present this essay examining Rabbi Sacks’s contributions to the field of Biblical commentary.

The first thing one notices about the biblical commentaries by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks is the cover art. Comprising volumes on Genesis through Numbers—as well as two companion volumes, Lessons in Leadership and Essays on Ethics—each edition of Covenant and Conversation is adorned with another seventeenth century European masterpiece, including several by Rembrandt.

The choice is suggestive. The paintings from this era, whether of the Dutch Golden Age or the Baroque tradition, collectively represent one of the crowning achievements of Western art. Likewise, one of the central arguments of Covenant and Conversation is that the five books of Moses should be seen as essential and foundational texts for Western civilization. And with the caveat that “Judaism is a complex faith[,] there is no one Torah model of leadership” (Exodus, 113), the personality that looms largest in Rabbi Sacks’s biblical interpretation is Moses. While this is to be expected for a corpus—Torat Moshe (Joshua 8:31)—that has traditionally borne his name, the Moses that emerges in Rabbi Sacks’s writings embodies two of the core themes of Covenant and Conversation: the challenges of wielding power, and the importance of building a just society that will stand the test of time.

Rabbi Sacks employs two different strategies for uncovering each theme in Moses’s career. In eliciting the first, Rabbi Sacks plays the role of textual interpreter. Through close readings of the Biblical text, the traditional Jewish commentaries, the classics of political theory, and modern social science, he explains how Moses dealt with various leadership challenges. We the readers are meant to learn from Moses’s personal example through the Torah’s usually positive—but sometimes quite critical—depiction of the legendary prophet.

In developing the second theme, by comparison, Rabbi Sacks seeks not to explain the text, but to comment on the fundamental structures of Jewish life and community throughout the ages. What institutions, offices, and ethical principles characterize the Torah’s vision for a good, lasting society? Here we are less interested in literary analysis of Moses as a singular individual as we are in the Torah’s grand vision for the future of human flourishing.

But whether Rabbi Sacks trains his focus upon scripture or upon society, the life of Moses proves instructive.

I.

Rabbi Sacks prefaces his commentary on Exodus with an unequivocal statement on the dangers of power, “Power destroys the powerless and powerful alike, oppressing the one while corrupting the other” (Exodus, 2). For Rabbi Sacks, wariness of power animates Moses’s entire career. This is not to say that Moses found power inherently evil. He was simply convinced that there is only one being—God—to whom absolute power truly belongs. God could wield this power because He truly understands the necessity for evil and human suffering in the grand scope of history. But human beings are not capable of this, nor, thought Moses, should they want to be. After all, to be human is to rage against suffering, even when such feelings may, from the perspective of eternity, be misplaced. Moses feared losing this quality, and so always feared power. For Rabbi Sacks, this explains Moses’s reticence to gaze upon God at the burning bush, described in the Bible and later rabbinic texts (Exodus, 40). Unlike so many other heroes of the ancient world, Moses did not aspire to divinity.

Of course, no leader can avoid exercising power, and Moses is no exception. But Moses knew—and this, for Rabbi Sacks, is perhaps his greatest quality as a leader—that human power requires strict, conscious limits. In fact, one of the most powerful things a great leader can do is empower others. This motif suffuses Rabbi Sacks’s characterization of Moses. Moses, for instance, maintained a remarkable ability to appreciate the talents—and even different moral foundations—of others. Drawing upon the nineteenth century Lithuanian commentator, Netziv, Rabbi Sacks explains Moses’s decision to heed his Midianite father-in-law’s advice in founding a comprehensive judicial system as born out of a recognition that whereas Moses himself intuitively embraced the strict demands of justice, it was important for the Israelites as well to have leaders who excelled at promoting compromise and reconciliation (Exodus, 129-130). In similar fashion, while Moses viewed Korah as a genuine threat to his legitimate authority, he saw Eldad and Medad—potential prophetic rivals appearing in Numbers 11—as capable figures whose leadership, rather than undermining Moses’s authority, would in fact magnify his influence. He therefore chastises his disciple, Joshua, for accusing them of usurping Moses’s prophetic prerogatives (Numbers, 222-224). The general principle at work here, in Rabbi Sacks’s formulation, is that “no one individual can embody all the virtues necessary to sustain a people” (Exodus, 130). Moses, accordingly, shared power as much as possible.

Questions of power lead Rabbi Sacks to consider Moses’s “leadership style” (Numbers, 128). In the history of traditional Jewish biblical commentary broadly conceived, Rabbi Sacks may be the first since Philo of Alexandria to treat this topic holistically. The results are certainly in keeping with a picture of Moses as sensitive to the challenges of power. In direct contrast to much of contemporary religious leadership, Moses led by listening rather than telling—by making space for others (Lessons in Leadership, 255). It is of special significance in this context that Moses was surrounded by confidants—in particular his brother, Aaron—whose worldview so contrasted with his own. Rabbi Sacks juxtaposes Moses’s stoicism, for example, with Aaron’s deep passion. When tragedy strikes their family in Leviticus 10, Moses is strengthened by his faith in God’s covenant, while Aaron is inconsolable. Rabbi Sacks represents both as legitimate reactions to catastrophe, and sees them both playing out in tandem over the subsequent course of Jewish history (Leviticus, 155). Tellingly, it is precisely when Moses gives in to his grief in the wake of his sister Miriam’s death—when he, in effect, becomes Aaron—that he loses control at Meribah (Numbers, 272-275). This leads directly to God punishing Moses by refusing him entry into the Land of Israel.

In fact, Rabbi Sacks consistently describes even Moses’s leadership failures in terms of the challenges of power. At the nadir of Moses’s career, the Korah rebellion in Numbers 16, the Biblical text appears to depict a Moses who has lost control. He beseeches God to make an example of Korah—the only time in the Torah that Moses ever asked God to punish another person. This show of force only worsens the rebellion. In Rabbi Sacks’s interpretation, Moses’s mistake here was to read criticism of his office as personal criticism. The ability to distinguish between one’s public role and oneself is the difference between viewing oneself as wielding power, and viewing oneself as powerful. “It is hard,” writes Rabbi Sacks, “not to see this as the first sign of the failing that would eventually cost Moses his chance to lead the people into the land” (Numbers, 216).

For a person so preoccupied with power, one might have imagined Moses developing into a Nietzschean skeptic, sighing at “the comedy of existence.” But it is here that Rabbi Sacks identifies Moses’s true greatness. Throughout all his travails, Moses never became a cynic. This is how Rabbi Sacks reads the final verses of Deuteronomy, describing Moses’s eyes as undimmed until the moment the Almighty reclaimed his soul (Lessons in Leadership, 301-302). Moses feared power, and struggled with it, but he never let it consume him. And it certainly did not sour him on the beauty and mystery of human existence.

II.

In Rabbi Sacks’s view, the Torah’s project is to articulate the principles for constructing a just and lasting society. In this long-term project, Moses appears not as a literary character, but a moral and political visionary. Although Rabbi Sacks’s conception of the (or an) ideal Biblical society owes a great deal to Moses at every turn, perhaps the single greatest insight that he attributes to Moses is this: a healthy society must actively cultivate future leaders.

Moses, in Rabbi Sacks’s reading, saw as society’s greatest enemy what economists refer to as the “discount rate,” or the tendency to value the present at the expense of the future. In response, Moses consistently emphasized the need to take account of future generations.

On the basis of a Talmudic passage in Tractate Kiddushin (32a-b), Rabbi Sacks points to the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15 as the earliest instance in which Moses stressed the danger of relying for leadership upon once-in-a-generation supernovas, like Moses himself (Exodus, 111-114). Stable, dependable leadership would be an absolute necessity in ensuring Judaism’s continued vigor. This theme repeats itself frequently in Rabbi Sacks’s characterization of Moses. Most importantly, it forms the basis for Rabbi Sacks’s interpretation of the Temple as an institution—the introduction of which into Jewish life he associates with Moses. That is, in the wake of the crisis of the Golden Calf, one of the central events in the book of Exodus, the Biblical text depicts Moses as the only thing standing in the way of God’s wholesale annihilation of the Israelites. Moses recognized this situation as inherently unstable. No people could build a lasting society if they depended for their survival upon prophets—the supply of which is by definition unpredictable. What the Israelites needed, Moses argued, was some mechanism for ensuring that future generations would have a steady stock of leaders. In response, God instituted the Temple and its priesthood. “The priesthood,” observes Rabbi Sacks, “represents continuity immune to the vicissitudes of time” (Leviticus, 12).

Concern for the future further explains why Moses’s temporary embrace, in Numbers 11, of the in loco parentis mode of leadership proves so disastrous. In this episode, Moses had suffered an emotional collapse in response to the Israelites’ complaints. Rabbi Sacks contrasts this with similar complaints in the book of Exodus to which Moses had reacted with equanimity. He resolves the discrepancy by noting that over the course of the Biblical narrative, Moses appears to become increasingly convinced that, as a leader, he must do it all. By the time we reach Numbers 11, Moses began comparing his role to a nurse carrying a child (Numbers 11:12). “The trouble,” Rabbi Sacks notes, “is that if the leader is a parent, then the followers remain children” (Numbers, 129). Unchecked, unbalanced leadership may yield order in the present, but it stunts the social growth of subsequent generations.

Moses recognized that genuinely sustainable leadership is rooted in teaching. This, too, is a constant refrain in Rabbi Sacks’s oeuvre. A righteous society that wishes to remain so places education at its foundation (Exodus, 77-81). The purpose of this education is to transmit core values over long time-horizons. This is why Moses constantly exhorts the Israelites and their descendants to “remember” the significant moments in their history (Numbers, 157). The values that Moses was responsible for transmitting would take many generations to seize hold—to become a “culture.” Only a robust commitment to education and instruction would ensure these values’ continuity and vitality over the course of time. This sort of long-term thinking is an essential element of the Biblical ethos such that, as Rabbi Sacks notes, the historical narratives of the entire Hebrew Bible span roughly a thousand years. The Bible thinks in these sorts of increments.

In the end, perhaps the clearest expression for Rabbi Sacks of Moses’s commitment to the long-term gains of education is that the sobriquet by which he is known in Jewish literature and vernacular to this day is Moshe Rabbeinu, “Moses our teacher.” This reflects, Rabbi Sacks argues, the role that Moses embraced at the end of his life, in the book of Deuteronomy. When all was said and done, Moses was not a king, nor a prophet, but an educator (Lessons in Leadership, 243).

III.

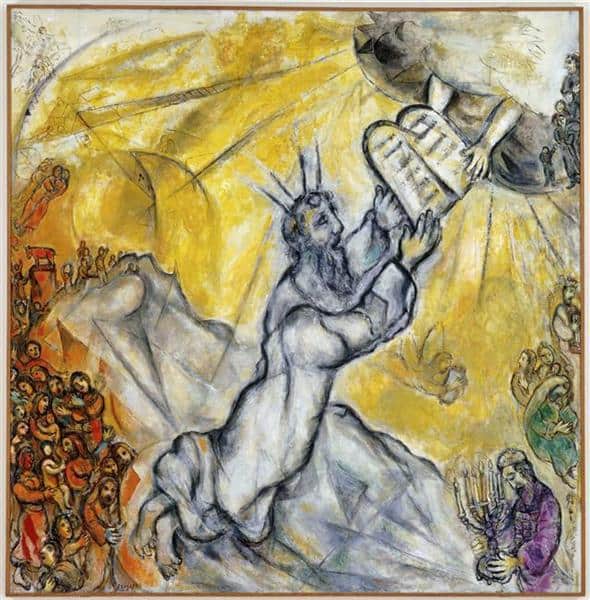

In considering Rabbi Sacks’s portrait of Moses—and more broadly, the former Chief Rabbi’s legacy as a Biblical commentator—my mind keeps returning to Rembrandt’s Moses Smashing the Tablets of the Law, the iconic painting that adorns the cover of Covenant and Conversation: Exodus. It strikes me that another masterpiece might have been even more fitting: Marc Chagall’s Moses Receiving the Tablets of the Law. After all, in Rembrandt’s work, Moses stands alone on a mountaintop, a lonely man of faith. This is not Rabbi Sacks’s Moses.

Chagall, by contrast, paints Moses’s encounter with God on Mount Sinai—in direct contradiction to the Biblical text!—as a crowded emotional spectacle. A joyous smile upon his face, Moses is surrounded on one side by the Israelites at the foot of the mountain, looking up at him in wonder. On the other he is ringed by contemporary figures—a bearded man lighting a menorah, a religious official grasping a Torah scroll, and other modern Jewish onlookers. Moses’s receipt of the Torah is not a solitary experience, but a communal one, a societal one. And its significance reverberates not just across space but across time, touching the lives of Jews—in truth, all of humanity—throughout history.

Rabbi Sacks’s Moses—like Chagall’s Moses—is not an inscrutably righteous person perched atop an unscalable mountain. He is a man who can only be understood in the context of his people, his followers across the generations, and the great moral and political philosophy he helped birth. He is a leader whose teachings guide the Jewish people, inspired Western Civilization, and continue to speak to the great human questions of the day.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.