Shira Eliaser

“Fetch it yourself,” I told Bat-Ya’anah. “I have better things to do with my time than be your water bearer.”

Bat-Ya’anah threw a handful of sand into the coriander I was grinding. “Like what? Spin badly, cook atrociously, and stand in the doorway to frighten strangers? Make yourself useful, woman, or Abner will send you back in destitution to your father’s house.”

I spat at Bat-Ya’anah’s feet. “Don’t you give orders to me, Long Neck. The way you talk, you’d think you were already wife to Abner. Tuck that stretched throat of yours back into your dress, for there are several others ahead of you.”

Bat-Ya’anah’s lip curled, for Abner was notoriously free with his maidservants. “You should know, of course,” she sneered, “about waiting for a husband. Perhaps if you tuck your head low enough and bare your bosom, old man Ner might take you. Do you think he’ll be blind enough in seven years not to notice that ghastly mess on your face? Now, fetch the water for my lord’s men before your womb shrivels up from old age.”

She left before I could answer back, and just as well, for I had no wish to be present when Hammutal found the sand in the coriander and demanded an explanation. So I fetched up two jugs of water and carried them off toward the captains’ tents.

* * *

The prisoner cowered in the dirt before the captains of the host.

“My lord the King,” Shimeah thundered, “King Agag of Amalek―alive. The Lord God delivered him into my hand. His armor I have destroyed as the Lord bade us, but his person I give to you, to do with as the Lord sees fit.”

King Saul surveyed the dirty wretch at his feet. A smile slowly wove its way across his face, and he licked his lips. After a long moment, he signaled for his sword. His armor bearer fetched the weapon and buckled it about the king’s person.

“So perish all the enemies of Israel!” called Abner, and the cry was taken up by the host. “The enemy of Israel! Let him perish!”

The king, who had neither spoken nor moved until now, strode toward the prisoner and stamped one heavy foot onto the Amalekite’s back. He drew his sword.

“The enemy of Israel!” cheered the captains. “Long live my lord the King!”

“My lord king!” gasped the prisoner. “O great and mighty king of Israel! Mighty are you in battle and gracious in conquest! Raise your eyes and enjoy the great victory you have achieved this day. Your god has given your enemies into your hand and laid their king at your feet; how could you hear my lamentations and my submissions if I were sent to the grave?”

“Thus the uncircumcised!” jeered Abner. “Kill him, my lord!”

Saul ignored him. The twisted smile was still playing about his face. “Plead, uncircumcised dog,” he told the prisoner. “Plead before the God of Israel who demands your life.”

“The god of Israel is indeed the god of battle, mightiest of the Heavenly Host!” wheezed Agag. “To him is the victory, and to his anointed king. Let me but eat bread in your dungeon, and I shall proclaim your sovereignty for all time. Let me be but the least of my lord’s servants, so that I may declare the greatness of your god. Let your name henceforth be Saul, King of Kings, whose right hand is kissed by princes and whose foot is kissed by anointed kings. But let it not be said of my lord King Saul that he stretched out his hand to spill the blood of his brother, the anointed one of Amalek.”

For a long moment, the world stood still.

Then Saul laughed. Before him stretched the smoking remains of his enemies, and behind him amassed his faithful army, undiminished by casualties and rich with plunder. And never before had an anointed king lain at his feet, offering such submission to a king of Israel. The God of Israel was indeed generous in victory.

With a swift, sudden motion, Saul seized the prisoner by the hair, spat in his face, and cut off his beard. With a great shout, the other of the soldiers closed in, and the rest of the scene was hidden from view.

* * *

“Ho there, Water Fairy!” called the dirty, beaten bundle on the ground in front of the captains’ tents. “I’ll have some of that, thank you.”

“Keep your dirty tongue between your teeth,” I told him. “This water is for my lord and not for you.”

“Oh, come now!” The prisoner assumed a tone of wounded innocence. “Is that any way to treat your master’s guest?”

“Guest!” I snorted. “You’re a walking dead man, that’s what you are. You’re a headless corpse on legs. Don’t put on airs because you’ve been given over to my lord’s soldiers instead of being beheaded on the spot. I’d be watering a skeleton if I gave this to you.”

My lord Abner, whose hands I was washing, snorted with amusement. “That’s right, that’s right,” grinned Agag good-naturedly. “Toss your head so that your bangles shake. Let the serving girl of my lord Abner rejoice, for this day a king lies bloodied at her feet, and he must beg her for his sustenance.”

I was going to toss my head, of course, but I stopped, lest it give the Amalekite satisfaction. But the little worm saw the twitch in my chin and divined my thoughts. “Ah, ah, ah!” he scolded me. “Such pride!”

Abner smiled at the drama and chucked me under the chin for providing him with such entertainment. This was high praise from my lord, who had no shortage of winsome concubines and generally kept his eyes far away from my disfigured features. Wordlessly, he signaled to me that I might indeed water the prisoner. “Take this dog into the tent,” the captain ordered idly. “And see that he is made presentable until my lord the king decides his fate.”

* * *

“Come now!” The prisoner grew imperious. “The wound will fester if it is not dressed. Bring oil and clean linen.”

“It will fester in your grave as the worms devour your flesh,” I told Agag. “My lord bade me wash you, but he said nothing about wasting oil or linen on your dead body.”

“Are the olive presses of Israel so barren that you can spare no drop for a king’s wounds?” grumbled Agag. “Is this the bounty of your god? Come, come, woman. You’ve had your fun making sport of your master’s guest. Now dress my wounds and attire my body. My lord captain bade you make me presentable, and it will not please him to find his clean garments stained with the oozings of my body. I see a cruse of oil there on the table. Now bring it me.”

Ah, our lot. Men order and women obey. I dressed his wounds and cleaned his garments as best I could. “That’s better,” said the conquered king genteelly. “You are learning. I don’t mind a little impertinence in a serving girl, as long as she knows her place. As you serve me longer, you’ll get to know my moods, and you’ll learn when to speak your mind and when to be silent.”

“You may wear my lord Abner’s soiled garment,” I told the prisoner. “But that doesn’t make you my lord. Neither am I your maidservant. Know your own place, uncircumcised wretch, for you are now king of worms and maggots, rather than men and women.”

“Did you not hear the captain’s command?” Agag looked at me sternly. “You are to attend to my needs and make me presentable until your lord the king assigns me my place. You have a new master now, girl, and he will be kinder to you than the old, for my wants are few and I shall let you sit and spin when my needs are satisfied, not send you running hither and yon about the camp. Please me, and I will even give you some of my portion from the king’s table.”

“Your portion?” I laughed. “A sword on which to impale yourself? Your portion is to hang in pieces from the walls of Gilgal. The entire valley knows it—that’s why they’re learning to speak Hebrew!”

The prisoner smiled. “You speak as an ignorant wench. You know nothing of politics. Watch a few days, and you will see the ways of kings. And when we have grown old together and you wash my feet in your king’s palace, I will remind you of this day, when you thought that the king of Israel would slay the king of Amalek as he would a fox in the field.”

“The God of Israel wants your head,” I told the ignorant captive. “Our nation was told to annihilate yours, and you are no exception.”

Now Agag was laughing, smacking the floor in his mirth. “You poor girl! Your father was no courtier, nor did your mother weave tapestries for the queen’s house. Know then, serving woman, that no anointed king has ever killed another except as an accident of battle or in the heat of a quarrel over the throne. What would the gods say to see their anointed one lying cold on the earth, his royal blood pooling like that of a sacrificial ram?

“Perpend, my girl,” he went on, in a more serious tone. “What would the people think if they saw one with holy oil on his head struck down? That his god had no power to defend him? That he was no longer the chosen one of his god? That an anointed king could be slain in cold blood like any other man? And what would this mean for the anointed one who struck the deadly blow? Could not he also be struck down in the same fashion?

“Kill a king, unschooled one, and you kill more than a man,” Agag told me. “You kill the order of the world. You kill the fear of the throne, the awe of kings. Your king is no fool. Should he kill me, he would invite the killing of kings throughout his land. Any mutinous soldier, any devious prince might raise his hand against the king without fear. The anointing oil would not deter the knife of the bandit chief, nor would the favor of his god stop any ambitious shepherd from rising up to steal his throne. My blood would curse his land, and it would plunge into anarchy and destitution.”

I scrubbed Agag’s girdle with the washing brush and did not respond to his words. The prisoner helped himself to some skins and a blanket to make himself a bed. He closed his eyes to rest while I labored, and when I was finished, I tossed the girdle and the garment at his feet.

“Ah,” said Agag, opening his eyes. “Most welcome. Now I will divest myself of the captain’s robe and put on mine own again.” The rest of his words were said to my shoulder, for I had no desire to see this spectacle, and I made to leave the tent. He went on, though: “And you can fetch me some bread and meat to eat, for I am faint and would refresh myself.”

I would have closed the tent flap in his face, but Agag was close behind me. “Bread and meat, serving girl of the captain! And a draught of wine would not be unwelcome.”

Agag’s words were almost drowned out by the delighted screech of Bat-Ya’anah, who sat by the cooking fire in front of the tent. “So there is the delinquent one! Hammutal has been looking for you, and she seeks to know why the coriander for which she sent you is not yet returned. I hope you have been enjoying yourself beating that prisoner, for you are certainly due a beating when she finds you!”

“Tend to your business, cooking-woman,” Agag told Bat-Ya’anah. “And give my serving girl a bowl of whatever that is, for she is sent by your master the captain to find me some refreshment.”

“Ah, ah, ah!” laughed Bat-Ya’anah. “So you’ve found one who will have you! I hope the uncircumcised one likes charcoal, for that is all he will taste in your cooking. Take care, woman, that you do not splash again from the boiling pot, for there are still some spots on your face unblemished from the last time!”

I would have cursed her for a meddling vixen, but Agag was quicker. “Take care, take care!” he shot back. “Be careful to whom you taunt, you of the seething words. That is my serving girl to whom you rail, and her tongue is quicker than your ill-restrained thoughts. She speaks her mind, that one, and holds nothing back. Be careful, lest she curse you with blindness and leprosy for your ill-considered speech!”

“You make a fine match, you with your bloody thigh and she with her repulsive face,” scowled Bat-Ya’anah. “A plague on both your loins!”

He was used to jesting with the serving women, I’ll say that much for him. My lord King Saul would have been stricken speechless at such an affront and would have beheaded the wench on the spot rather than respond to her taunts. But this one just smiled like a wolf. “A fine match to be sure,” he purred. “A fine match that my lord the captain has arranged for us. And I hear you are in luck, for the captain has arranged an even better match for you, you of the cook pot. You he has matched with his horse, for with those enormous teeth and that great long neck, you should prove the mother of many a prize stallion!”

A great shout of laughter went up from the women in the courtyard. The fires flickered with the breath of women, hooting and wheezing for sheer merriment. Bat-Ya’anah covered her face and fled. Agag looked pleased with himself as he surveyed his work, winking at me as if we had planned together some great attack. “Run, little mare!” he called after her.

I drew up my scarf to hide my smiles, as I went to sift the sand from the coriander seeds. And in the stores beside my work place, I espied some bread and olives.

* * *

“There you are!” cried my prisoner gratefully. “I thought perhaps you had gone to harvest the wheat yourself. No matter, for here is my meal. Give it me.”

I handed the bread board to my charge. “Ah, no meat,” he sighed, surveying the food with disappointment. “The king of Israel has not yet made up his mind. Still, I should be grateful for what I am given.”

“You do that,” I told him. “Bad enough that I must pour good victuals into a bowl that will soon be shattered.”

“Your mind is simple and your memory short,” the captive king scolded, filling his mouth. “Remember my words of this night. The king of Israel may imprison me, he may put my eyes out or disfigure my manhood, but he will never be so imprudent as to spill my blood. Now, sit and wait upon me, for that is the custom of the king’s serving woman.”

“I will not,” I told him. “I have other duties long-neglected because of you.”

“What, you’re going off to do the bidding of that long-necked horse face?” teased Agag. “Don’t give her the satisfaction. Stay and wait upon me instead. I assure you my bidding will be much more pleasant.”

“I’m sure it will,” I shot back. “And so are all the maids of Benjamin. Such is not done in Israel, for our king’s wife is one and she has no rival.”

“What need have you for the maids of Benjamin?” Agag pursued. “What honor do they give you when you sit among them? Do they praise your weaving and bless the work of your hands? Let the haughty ostriches keep their own counsel, and you will wait upon your master.”

“May you be satisfied with twenty more beatings from the hands of Abner’s men,” I snorted. “Such is not done with us.”

“Yes, yes,” smiled Agag. “Stretch forth your neck so that I may see its whiteness. Had I any, I would deck you with beads. Who has paid your father a bride-price, that you bind yourself up for his sake? To whom will he betroth you, the captain, that you keep yourself for him?”

I took the empty board from the scoundrel’s lap, taking care that my fringes should slap his face. I took no pains to hide the scowl on my face, and my prisoner grew merry.

“Sold you without a thought did he, your father of the greedy fingers? No dowry for the bride, bar the silver that crossed his palm? And now you keep yourself so clean, serving wench of the captain, desisting from the pleasures of womanhood for his sake? A king would have you in his lap, and you toss your head at him for the honor of the one who consumed your bridal-mohar?”

“Had I not been sold to Abner,” I informed the sly wretch, “I would have starved, and my brothers with me. My father’s house is not wealthy, and here I have a place.”

Agag was ready for me. “Your place, girl of Israel, is to serve me as your lord bid you. Wherefore do you not take pleasure in the duty? Your days are long, and your bed is not soft; why refuse you the king who offers for your pretty braids? Say to the other women, ‘Ah! What you know!’ and to your heart, ‘I was queen for a night.’ Let the others chatter around the cooking pots. You alone shall know that you have been with a king.”

* * *

As the male child within her stirred to be born, the spirit stirred within Hannah. She said to herself, “I will name him Sha-ul, Saul, the asked-for [sha-ul], the wanted one, for I have borrowed [sha-al] him from the Lord.” For this child she had prayed, and his life she would dedicate to his Maker. Yet as the babe was born, the Lord deceived her; the spirit within her was whisked away and sent to another, and in its place a new soul was lodged. The child for whom Hannah prayed was delivered of another, and from her womb came a different one.

“This one,” stuttered Hannah as she tried to remember the spirit now fled, “shall be called Shemu-el, Samuel, for I have borrowed him [sh-iltiv] from the Lord.” So came the prophet Samuel into the world. But Shaul, the asked-for, was born to a woman of Benjamin, in another time and another place. This is as it was meant to be, for if the two had been of age and looked into each other’s faces, it would have been as if they had looked into two mirrors, and they would have divined the truth. Indeed, the truth was long suspected by Samuel, who was himself a man of God. But Saul never saw his own face in the prophet’s, though Samuel glimpsed his own beneath the crown.

* * *

In the military camp of Israel, the captains cried out in triumph and the servants in admiration, cups aloft to the name of King Saul. And as Agag cried out as well, the prophet Samuel awoke.

“Blessed are you in the Lord’s name,” Saul greeted the prophet with transparent overenthusiasm. Had he not been so busy with his own affairs, he would have noticed how the old man’s eyes were red with weeping and how the state of his garments bespoke a night without sleep. “I have fulfilled the Lord’s word!”

“Oh, have you indeed?” croaked Samuel. “Have you, now? So what is this bleating of sheep and lowing of oxen that I hear?”

Saul swallowed guiltily. He had been expecting this, for his orders had been to refuse all spoils of war. He had erected a monument at Carmel and reserved all the looted livestock for sacrifices in an attempt to atone for this omission. It had really been too much to hope that all might have been completed before the man of God found him out.

“The men took pity on the fine livestock,” Saul explained. “They spared the poor beasts and would not destroy them. The deed was done before I arrived; I had no control of the matter. However, I can assure you that everything else was completely wiped out; only these that you hear have been saved to sacrifice to the Lord your God.”

“The Lord my God,” repeated Samuel stonily.

“Blessed be His name.” Saul’s eyebrows arched at the prophet’s dark mutterings. The king’s excuse was watertight, he had made sure of that—had the man no respect for the sacrificial service? Saul assumed a look of pious forbearance for the old man’s ingratitude and began to busy himself with his morning tasks.

“The Lord my God told you that everything was to be destroyed.” Samuel spoke low and dangerously.

“The people saved the beasts long before my arrival,” Saul shot back. “You must not blame me, for I could not stop them.”

“Then you are relieved of your station!” the prophet thundered.

Half into his mantle and half out of it, Saul froze. The prophet’s insolence was unthinkable. Such a remark would have meant death for any other man, uttered to Saul, king of kings, whose hand was kissed by princes, whose foot was kissed by anointed ones. Hot rage and cold shame tied his tongue, and in the ensuing silence, Saul felt that his heart would burst.

“Shall I tell you what the Lord said to me last night?” said Samuel, more quietly.

“Speak,” croaked Saul.

“Though you may be small and weak in your own eyes,” Samuel told Saul—a bitter irony, for Saul was six feet, five inches tall and stood head and shoulders above every other soldier in Israel—”you are the head of all the tribes of Israel; the Lord has anointed you as His king. To Him above are your responsible for the conduct of your men. If you cannot control their actions, you are no fit king. Moreover, you have failed in the task that God set for you, for He ordered you to wipe out the sinners of Amalek with everything they had, so that their culture might never rise again. You were to be as holy thunderbolts in God’s hands, not as a league of bandits going after plunder. Why did you not do this?” The old man’s voice broke. “You say you have fulfilled God’s word, and yet here I find you blundering after spoils! Why did you not destroy them all? Why did you do wrong by your God?”

“I did no wrong!” cried Saul defensively. Now his temper was rising, as he struggled into his robe and drew himself up to his full height. “I slew them all, down to the last child and the last donkey. I carried off their king alive to give glory to God’s name, and the people saved the animals so that we might sacrifice to your God! I have brought honor and glory to God’s holy being, and you come before me to tell me I did wrong by doing so?”

“What does God desire more, sacrifices or obedience?” wailed Samuel. “He would rather you listen than sacrifice, for your attention is worth more to Him than the fat of rams. You might as well have been practicing witchcraft and worshiping idols for all the good you have done today. Heard you nothing of God’s purpose before you went into battle? Because you have rebuffed the Lord’s words, He has rebuffed you as His king!”

Saul wilted like a cut flower. His course was run, his excuse was rejected, and there was no more advantage in continuing on this way. The prophecy had been uttered; now was the time to repent and beg the prophet’s pardon before the prophecy came true.

“I have sinned,” he confessed humbly. “I have disobeyed the Lord’s words and your words. I was too shy to rebuke the people for what they had done, for I feared my status would be lowered in their eyes. I am justly recompensed for my weakness. Now, I pray you, pardon my sin and come back with me, so that I may bow low before the Lord.”

There. He had said it. All the words that had been whirling through his mind, all the little insecurities that had been plaguing him since Samuel had once pulled him from the crowd with the anointing oil in his hand. All his worries and fears. The confession was formulaic, perfect. He had listed his sins and acknowledged the just consequences. There was no way the prophet could refuse him.

“I will not return with you,” Samuel told him, gathering up his skirts. “I am not a priest on Atonement Day to cleanse you of your sins for you to repeat them the following day. Your deed is done; your kingship is over.” And with this he turned toward the door, less because his message was over than lest Saul see his face.

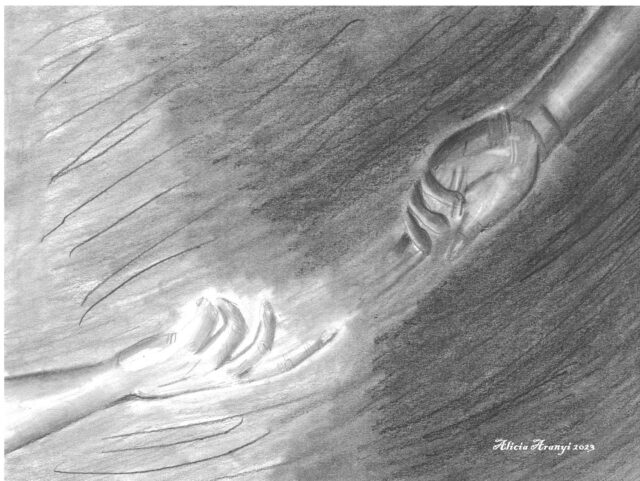

Saul stood paralyzed as the prophet who had anointed him now turned to go. But as Samuel pushed his way out of the tent, Saul’s frozen tendons came to life, and he sprang forward in desperation. “My lord Samuel! O man of God! Wait!” In panic, he seized the wing of the prophet’s cloak and pulled. The prophet turned; the king jerked, and the cloak tore between them. Samuel stared wordlessly at his torn garment.

“Now I too will be dishonored before the people, appearing before them in such a state,” murmured the prophet with a bitter smile.

“Take the cloth,” Samuel went on, as Saul stared in horror at the wing in his hands. “Take the cloth and return it to my garment. Repair the damage you have done. Make my cloak whole once more.”

“I… I cannot,” mumbled Saul. “I have not the skill. But I can fetch a woman who can—”

“As you have done here, so too did you do on the battlefield of Amalek,” Samuel told him sadly. “The Lord has torn the kingship from your shoulders and given it to your comrade who is more worthy of it. As you cannot repair this split, so can you not undo that one. The Enduring One of Israel will now do what you should have done; neither will He relent nor change His mind, as you did. He is not a man, that He should relent. He does not relent… no… he does not…”

For the first time, Saul looked down into the face of the prophet Samuel. The dark circles under the eyes were his own dark circles; the tears streaming down his cheeks were his own tears. The eyes were his own tortured eyes. For a moment, he felt himself looking at his other self, a life that could have been but was never his. The pain that Samuel felt was his pain. No shame could befall him that this poor old man did not feel as if it were his own. No absolution could come from those eyes unless it came from Saul’s own soul. And Saul knew at that moment that neither of their souls would ever know such peace.

The cloth dropped from Saul’s hands. Very slowly, very carefully, he gathered the weeping prophet into his arms. For a long moment they stood there, until Samuel composed himself and Saul released him.

“I have sinned,” whispered Saul. “I have sinned, and there is no returning. But only you can help me to bear it. Please. Return with me and honor me before the elders of my people, so I can worship the Lord with them. Let me worship the Lord your God. When I called Him so, I spoke more truly than I had intended, for He is the Lord your God and will have none of me. Nevertheless, though He reject me, I shall still worship Him.”

* * *

The prophet’s early arrival threw our entire camp into a tumult of preparation. We had not expected his holy person to grace us so early, and those women who were not already awake were shouted out of their beds by Hammutal and hustled to prepare for the feast that would surely follow the sacrifices. The women who saw to the linen were also ordered hither and yon, for all the captains needed clean robes to stand before the altar, and many had not immersed themselves since the battle of the day before. I was dispatched to the captain’s tent to bring water and clean linen to all who needed.

“Your death approaches,” I told the prisoner. “The man of God has come to see the Lord’s word done.”

“None in Israel sacrifices mankind,” Agag grinned, turning over from his makeshift bed. “Your god has no stomach for it.”

“Perhaps you will be the first, then!” I snorted, helping him to his feet. “I can’t think why else my lord king has spared you.”

“To sit at his table and discipline his saucy maids,” winked the king. “To come in chains before him on feast days so I can beg again and again for his continued mercy. To get all his slave girls with child so that his men may be multiplied and his goods increased.”

“Don’t give yourself so much credit,” I told him, throwing a garment about his shoulders. “You’re about as potent as raisin water. You couldn’t get a stuffed prune with child; I of all women should know!”

“Then you must give me another chance, eh?” Agag made a grab for my hip, but I slapped his hand aside. When would the wretch be serious?

“Another chance?” I snorted, fetching his sandals from where he had thrown them. “When? In the two minutes before the soldiers fetch you out? Stop building palaces in the air—already they’re sharpening the swords for your head.”

I was still fastening his sandals when the door opened and the two soldiers came in. “The prophet Samuel calls for him,” said they. “Make way.”

Agag chucked me under the chin as I stood up. “Surely the bitterness of death has passed,” he smiled. And then the two men took him, and he was gone.

They say the man of God hewed him in pieces before the altar. He was an arrogant goat from the start, and it served him right.

* * *

I saw no more of Saul or Abner, or the war which followed the raid on Amalek. The following week I was sold to a Medanite trader, who took me east with him into the land of B’nei Ammon. Ah, you say that an Israelite’s daughter is not to be sold, that she should be returned to her father’s house after seven years if her lord has not married her or given her to his son? So says the Teaching of Moses? Well, good for you that you are such a scholar. You tell my lord Abner then; if you’re lucky, he’ll be able to read two words from that scroll you’re thrusting under his nose. Tell him that he has to keep his disfigured maidservant who can’t cook and that he can by no means make any money on her. Tell him so, little scholar, and see how far you get.

The Medanite trader, as I was saying, was a wheezy old man with bad breath. He took me to bed out of habit, like a man picking grass by the side of the road. I washed his linen and bleached his smelly goatskins, and yes, scholar, he made me work on the Sabbath day. But all this changed, you see, when it became apparent that I was with child. He was an impotent old bag, that one, and he had never sired a child all the days of his life. As I grew large, my worth became precious in his eyes. I received portions from his table; I was called to the meat to wait upon the master’s guests. The duty was not so welcome to me, let me tell you, for the platters were heavy and the endless scurrying and bending made my feet ache. But there was no gainsaying the master; he wanted all his friends and brothers to see his handmaid, big with his child. He gave me a veil to hide my ugly face and patted me fondly when I passed his seat.

When I was delivered of a healthy son, his pride knew no bounds. A son for the spice trader of Medan, to inherit his goods and carry on his name! He called me Shupha, the fertile one, and gave me herbs for my milk and perfumes for my hair. He installed me in the mistress’s tent to nurse my son and gave me all the garments and jewels of his late wife. The sumptuous feast he gave when the child was weaned almost beggared our tribe. It was on that night, as I sat at the great table with my son upon my lap, that my husband introduced me to his brother traders as his wife, and I knew my position had changed forever. I bowed my head in wifely submission as the Medanite praised the gods for giving him this fertile wife and this fine son in his old age. All hail Ba’al, master of the male organ! All hail Astarte of the ever-round moon! A son is born to Medan!

I named the child Agag, for I knew better.

He is a good boy, my Agag, and he takes good care of me in my old age. He avenged my husband’s death at the hands of Ishmaelite raiders, and he dealt them such a blow that they have never bothered our goods again. Not a week goes by that my son does not visit my tent to lay a gift at my feet or bring me the meat that he has prepared specially for me. He remembers always that I have never developed a taste for swine’s flesh, and he goes out of his way to capture herds of the clean animals for my sake. I tell him he need not go out of his way, and he replies that no honor is too great for her who gave him life. Of course, then he asks me to find him yet another wife and I have to smack him.

It amuses me to see so much of his father in him. He does more raiding than trading these days, for the spice routes are no longer as safe as they once were, and he finds far richer pickings closer to home. He knows, of course, who his real father is. Why should he not? My old man has gone to Sheol where the dead know everything. Why should Agag not take pride to be the son of a king?

He is out on another raid even now, carrying off livestock and slaves from the other side of the river. He says “the other side of the river” to spare my feelings, when I know perfectly well that it is the men of Israel he harasses. It does not displease me that he should raid the tribe of Menasheh, for they are wealthy and numerous, and they ever oppressed my father’s kinsmen. A raider must take what he finds. My son gives them no more trouble than the Ammonite caravans or Moabite villages among who are his usual prey. And even if he did, it would serve them right, for the Israelite wife I took for Agag betrayed him with another, and he had to carry off a daughter of Canaan to take her place.

The grandchildren cluster around me now, begging for tales, and I must leave off this account. There are so many of them now, between the two wives and three concubines—if Ta’aniah’s suckling is healthy, it will be eighteen. They want to know about the conquest of the land and the battles of the gods; they remember everything, my little ones, and will not be satisfied with the same tale told twice.

See the little rascals in the fields even now, playing at Moses slaying Og the giant, or Othniel destroying cities to win the hand of the chief’s daughter. They are a fine tribe, my young masters. The Agagites.

* * *

אלה תולדות אגג, אשר היולד ביום מאסתה את דבר ה׳׃ שופעה הולידה את אגג ואגג הוליד את גבור־חיל׃ וגיבור־חיל הוליד את אודיסאיה ואודיסאיס הוליד את עבד־ות׃ ועבדות הוליד את תעניה ועניה ועניה הוליד את שנאה׃ ושנאה הוליד את המדתא והמדתא הוליד את המן

These are the chronicles of Agag, whom Shupha bore to the king of Amalek from the day the Lord’s will was rebuffed. Shupha begat Agag, and Agag begat Gibbor-Hayyil. Gibbor-Hayyil begat Odisias, and Odisias begat Abedut. Abedut begat Ta’aniah and Ani’ah, and Ani’ah begat Sin’ah. And Sin’ah begat Hammedatha, and Hammedatha begat Haman.

For my teacher, Dr. Esther M. Shkop, from whom comes the derash on the names of Shmuel and Shaul, as well as the importance of the regicide taboo in biblical narratives. And for my father Dr. Ted Karp, alav ha-shalom, who said it just goes to show how fast a woman can get pregnant.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.