Mark Glass

Author’s Note: This article was drafted during Hol Ha-Mo’eid Sukkot. As such, it was not written with any intent to have a greater resonance due to the tragic events in Israel. While readers are invited to derive strength from this article should they find it, it is not intended to explicitly address current events.

I.

The most jarring indication that something is profoundly wrong with Genesis 14 — the Abrahamic narrative best known as “the war of the four kings against the five” — is found in an admittedly unusual and deeply untraditional source for any religious reader of Tanakh: E. A. Speiser’s Anchor Bible Commentary.Though Speiser’s work may be theological anathema to many a traditional reader, a quick peruse of its contents succinctly captures one of the great interpretative challenges of not only Genesis, but of the entire Hebrew Bible.

Speiser identifies each and every narrative unit (themselves divisions of his own devising) with its Documentary Author, in keeping with his academic want. The reader thus encounters the labels J, E, or P — sometimes alone, sometimes combined, and sometimes annotated with additional question marks and the like — attached to each narrative unit’s title.

Save, that is, for two instances. The second of which, Gen. 49 (“The Testament of Jacob”), is not the concern of this article. But the first, in which Speiser offers a curious label for Gen. 14, is. Here, “Invasion from the East. Abraham and Melchizedek” is designated neither with any of the conventional J, E, or P labels, nor with any possible combination or annotation, but with a simple and mysterious X.[1]

In explaining his rationale, Speiser lists several significant and strange features of Gen. 14: “The setting is international, the approach impersonal, and the narrative notable for its unusual style and vocabulary.” Speiser thus declares the chapter to have been authored by what he terms “an isolated source,” the mysterious, unknown X.[2]

And while Speiser’s theology leads to unpalatable conclusions for many a reader, his textual observations need not be controversial. After all, his striking X is, ultimately, a useful and pithy articulation of the many (many!) interpretive challenges of Gen. 14.

Take, for example, the sheer length of Gen. 14’s introduction, as contrasted with the general economy with which Genesis tells the other stories of Abraham. In Gen. 14, the Torah provides the geopolitical context and backstory over eleven verses. Compare this with the main drama alone of the Binding of Isaac, which is told in a mere thirteen verses (Gen. 22:1-13), and the detail on offer in Gen. 14 is indeed uncharacteristic. In fact, Malbim is astonished by the lengthy introduction to this story, commenting on this verse that “there is no need to tell of all these [matters] in the divine Torah!”[3]

But it’s not only the amount of detail on offer, but also the style in which it is offered. Netziv, for example, notes one particularly unusual inconsistency in this narrative: though Chedorla’omer is explicitly described as the chief of the four kings (Gen. 14:4), he is the third in the list of kings in the alliance (ibid. 14:1).[4]

And the reason behind this is simple yet startling, given the Torah’s typical mode of narration. It’s because the Torah introduces the four kings in not their hierarchy but — of all things — alphabetical order: “Now, when King Amraphel of Shinar, King Arioch of Ellasar, King Chedorla’omer of Elam, and King Tidal of Goi’im” (ibid.).[5] And the Torah continues this highly stylized manner in v. 2: we are introduced first to Bera of Sodom, then Birsha of Gomorrah, then Shinab of Admah, and finally Shemeber of Zeboi’im — with the fifth king’s name unknown and thus unidentified.

Contrast this detailed, poetic list of kings with what is found just two chapters earlier. In Gen. 12, the Torah describes the ruler of the era’s defining superpower, the mighty and powerful Egypt, solely by his title, “Pharaoh,” without a second thought for any further personal details. Yet, it is only around twenty verses later that the Torah is giving the reader not only every name (save one), but cities as well — all listed in a neat, alphabetical format.

Between the Torah’s sudden narrative-specific obsession with detail, abandonment of any attempt at being concise, and novel approach for character introductions — not to mention that this is a story about a man unintentionally caught amidst a battle between ancient, powerful nations — a close reader of Gen. 14 would be forgiven for thinking that things appear more Tolkien than Torah.

II.

The interpretive problems of Gen. 14, however, only compound when looking beyond its opening few verses. After the chapter spends almost half of its verses setting the scene in a story that is ostensibly about Abraham, his role — when he finally appears in verse 12 — is, at first, entirely passive. The verse exists to simply state how Abraham gets caught up in this war between different nations. It is Lot’s capture in Sodom by the invaders that plunges Abraham into the war. In other words, between the lengthy geopolitical introduction and the prompt that drives Abraham into the war, it is clear that Gen. 14 isn’t really a story about Abraham as much as a story that happens to involve Abraham.

Still, more problems endure. Because, even when Abraham does appear — even when, after twelve verses (!), Gen. 14 becomes an Abrahamic narrative actually involving Abraham — he is described in a remarkable way. The verse relates that a fugitive from the battle brings the news of Lot’s capture “to Abram the Hebrew” (ibid. 14:13). But, as Nahum M. Sarna notes, this term ivri, “a Hebrew,” while found approximately thirty times throughout the Hebrew Bible, is exclusively used as an “ethnic term.”[6] That is, it is precisely when Tanakh wishes to characterize an Israelite’s foreignness to another nation that the term “Hebrew” is invoked.

Thus, the Joseph story — one defined by Joseph’s alienation while stranded in a foreign land — is replete with examples. Potiphar’s wife, for example, describes Joseph to her fellow Egyptians as “a Hebrew” (Gen. 39:14), while Joseph himself uses the term to describe his land when speaking before Pharaoh: “I was kidnapped from the land of the Hebrews” (Gen. 40:15). Similarly, the beginning of Exodus uses the term to contrast the enslaved Israelites with the Egyptians (for example, Ex. 1:15 and 2:11). And while use of the term within the Hebrew Bible dwindles, it is still found in the very way in which Jonah declares his identity to the sailors: “I am a Hebrew” (Jonah 1:9).

To put all of this another way, the characterization of Abraham as “a Hebrew” implies something incredibly perplexing: that the story’s intended audience is unfamiliar, not only with Abraham, but his story and nation — he is a foreigner to them — hence the description of him as “a Hebrew.”

But this description of Abraham is not the only thing that implies that the reader is reading a different type of Abraham story than usual. The Abraham portrayed in Gen. 14 seems to be an entirely different Abraham, personality- and proclivity-wise, when compared to all the other stories about him in the Torah. After all, “Gen. 14 Abraham,” as it were, is someone who gathers a small band of allies and transforms them into an army capable of routing and plundering a coalition of foreign armies, driving them from the land and saving Lot (Gen. 14:14-16).

Indeed, as Jonathan Grossman points out, the Hebrew Bible’s typical portrayal of Abraham as “a man of spirit, a prophet, a moralist who promotes justice, an excellent host, and above all as one who merits an everlasting covenant with God… is seemingly incompatible with the diplomatic strategist who divides his troops and leads them in a dangerous nighttime rescue operation.”[7]

Combine all the above with the startling fact that, unlike so many of the narratives of Genesis until now, God is absent as an active participant in the story. Though He is repeatedly invoked as a deity by both Abraham and Melchizedek (Gen. 14:18-20, 22), these invocations only amplify His absence from the story until this point, and thus the uncharacteristic nature of the entire narrative.

The broad thrust of everything until now can be summed up in one simple statement: Gen. 14 seems fundamentally different from all the other Abrahamic narratives and, indeed, from all the other narratives in Tanakh.

Or, to simplify it even further into one single (heretical) character: X.

III.

To begin to make sense of everything in Gen. 14, then, it must be re-read with the acceptance that it is not the typical biblical story. And even though this mentality brings clarity, even more problems must first emerge. Indeed, these further problems emerge from the story’s opening two words: Va-yehi bi-mei, “It was in the days of.”

Usually, these two words introduce the reader to a known and specific historical moment or era in which the narrative takes place, often paired with the introduction of a major personality of that era and thus the story. The clearest example of this is the opening to the Book of Esther, “It was in the days of Ahasuerus,” which then continues and explains that this is the same Ahasuerus who ruled a vast kingdom (Est. 1:1). In other words, the Book of Esther begins at the height of the Persian Empire, and its story takes place in the heart of the royal court itself with Ahasuerus a main character.

The Book of Ruth begins in a similar vein, setting its historical context within the Book of Judges — “It was in the days when the Judges ruled” (Ruth 1:1) — while the Book of Jeremiah uses the same phrase to quickly establish that Jeremiah’s career spanned different monarchical reigns (Jer. 1:3).

Gen. 14, too, begins by informing the reader that this story takes place in the era of the four kings: Amraphel, Arioch, Chedorla’omer, and Tidal — only here its purpose is confusing. In contrast to Esther’s Ahasuerus, Ruth’s Judges, and Jeremiah’s Jeho’iakim and Zedekiah, the names and eras of these four kings are unknown to a reader of Tanakh beyond the story, and many of their cities are broadly unfamiliar. By beginning with va-yehi bi-mei, it suggests that the intended audience is assumed to be familiar with these kings and their era.

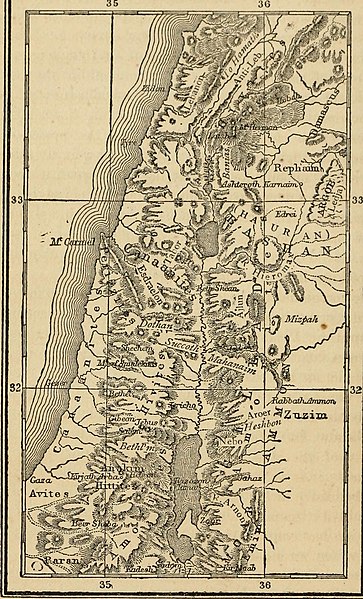

Then, the lengthy, eleven-verse introduction provides the reader with a seemingly unnecessary history lesson: that the five kings had been conquered by Chedorla’omer and his allies twelve years prior but had joined forces to rebel against him in the thirteenth year (Gen. 14:1-2, 4). They waited another year, however, until Chedorla’omer and his allies had succeeded in a different campaign — against the Rephaim, Zuzim, Eimim, and Horites (ibid. 14:5-6) — and had also subdued the Amalekites and Amorites to boot (ibid. 14:7). The five rebel kings then met Chedorla’omer and his forces at the Valley of Siddim (ibid. 14:3, 8-9), only to be swiftly defeated, so much so that the five kings hid or fled (ibid. 14:10). With Sodom and Gomorrah plundered (ibid. 14:11), Lot is captured, and thus Abraham enters the fray.

But this lengthy (by biblical standards, yet brief by historical standards) introduction, while uncharacteristic, may not be as unnecessary as it first seems, as it informs the reader of several pieces of important information regarding Chedorla’omer’s might.

After establishing his original conquest of the five kings, the text proceeds to describe a different campaign of Chedorla’omer – one in which he defeated some of the Hebrew Bible’s mightiest nations. This is testified to by Moses, who describes the Rephaim and Eimim (whom he identifies as the same nation known by two different names) as being “great and numerous,” similar in height and power to the tribe of giants, the Anakites (Deut. 2:10-11).

And not only is Chedorla’omer capable of defeating these nations, but also the Amalekites and Amorites — with v. 7 making it sound like this happened almost in passing (“on their way back”). And yet, despite having already fought two battles, Chedorla’omer makes quick work of the five kings’ rebellion.

All these details serve one, crucial narrative point. After devoting eleven verses to establishing Chedorla’omer’s power, they now magnify the military might of Abraham. Because, despite assembling a mere 318 men to his side (Gen. 14:14), he is able to do what neither the five kings could do (twice), nor the mighty Rephaim, Zuzim, Eimim, and Horites could do, nor what the fierce Amalekites and Amorites could do: defeat Chedorla’omer and his allies — and do so in one evening (ibid. 14:15).

However, significantly, this story showcasing Abraham’s military might is told in a unique style. It is not told from the perspective of Abraham, nor from the typical biblical narrator’s perspective, but is told, instead, from a different perspective entirely.

It is a story told from the perspective of someone for whom Chedorla’omer was a known figure of a known era, seen by the story’s use of the key phrase “It was in the days of.” It is a story told from the perspective of someone for whom Abraham was “a Hebrew,” a foreigner, an outsider. It is a story told from a perspective where the role of God is either unknown or unnoticed.

And this alternative, alien perspective also explains many of Gen. 14’s perplexing stylistic choices. The careful alphabetical arrangement of the various names, which reads less like a biblical story and more as a roll call, is not uncharacteristic if it is a familiar form for a different style, if it is what Grossman describes as “a technical list of participants taken from a military record.”[8] Likewise, the lengthy and excessive detail provided by way of introduction is not uncharacteristic if it is a familiar form for a different style.

Two possible explanations emerge. One, argued by Grossman, is that the Torah intentionally writes Gen. 14 in the alternative style of an ancient military chronicle from a foreign army to underscore Abraham’s military might. The other adopts, and adapts, Speiser’s X. The Torah consciously borrows an ancient account of the war and Abraham’s involvement and translated it into the Abrahamic narratives.

And, as strange an idea as this may seem, it makes more sense when considering the subject: Abraham’s military might. It is far more compelling for the Torah to use someone else’s testimony of Abraham’s strength and power — someone for whom Abraham was an outsider, “a Hebrew.”

IV.

Though this perspective offers a solution to the interpretative problems of the narrative — they mainly emerge from either the aping of the military style or the “borrowed” nature of the story — a simple question remains: Why? What purpose is served by such a strange story being included among the Abrahamic narratives?

It is important to recognize that not only is the Hebrew Bible generally economical in its words, but it is also economical in the stories it chooses to tell. The narratives of Abraham are, ultimately, a selection of vignettes from his life. They only begin when he is seventy-five (Gen. 12:4), contain several temporal gaps within (for example, Gen. 16, which concludes with Abraham aged eighty-six, while Gen. 17 begins with Abraham aged ninety-nine), and announce his death long before he died (Gen. 25:8, Rashi to Gen. 25:30, s.v. “min ha-adom ha-adom”).

Tanakh offers no complete biography of Abraham. Any story of Abraham , then, must serve a wider theological goal.

One answer, suggested by Grossman, is that this narrative highlights why Abraham is fit to gain the Land of Canaan. When all the other kings fled or hid from Chedorla’omer, only Abraham was capable of defeating him, only Abraham resisted and successfully repelled him. This is a story that reveals Abraham as the chief military power of the region — a point reinforced by not only the celebration of the king of Sodom, but also by the visit of a previously unmentioned king, Melchizedek, who had come to visit this new power in the land (Gen. 14:17-18).[9]

Another answer, also from Grossman, is that Gen. 14 is a story that reinforces Abraham’s rejection of Sodom. Despite having the opportunity and legitimacy to embrace Sodom, Abraham turns, instead, to Melchizedek, a fellow worshiper of God.[10]

I, however, would like to suggest an alternative answer, one rooted in Gen. 14’s unique testimony to Abraham’s military might — might that not only gives him the power to repel a powerful coalition of armies, but to draw the other kings of the land to seek allyship with him.

In a 2020 article for The Lehrhaus, Tzvi Sinensky closely examined the biblical word gevurah, and thus challenged the term’s typical meaning that connotes strength, power, and,by extension, raw masculinity.[11]

Crucially, for the purposes of this article, is Sinensky’s assessment of two competing narratives often told regarding Judaism’s perspective of strength and power. One narrative takes biblical heroes such as Samson, Saul, and David, and sees their physical prowess as worthy of emulation — culminating in secular Zionism’s adoration of the Hanukkah story and “the Maccabees as warrior-heroes” restoring “the classical biblical paradigm of the soldier.”

The other narrative is one in which the talmudic rabbis pivoted Judaism away from glorifying physical power towards moral power: strength and conquest were reimagined; “the hero no longer defeats his enemies on the battlefield, but “conquers his evil inclination” (Avot 4:1) and pursues victory in the study hall.”

Sinensky assesses these competing narratives succinctly: “Of course, both narratives are facile,” with the rest of his article redefining the term gevurah to prove that, in truth, “physical strength is neither inherently glorified nor vilified in the Torah.” Invoking the Hanukkah story — given that the article was published at Hanukkah time — Sinensky insists that the “most important part of the Hanukkah story is not the fact that the Hasmoneans were warriors,” but that their military prowess “was used toward a positive end.”

Ultimately, might and power are to be used in the service of those in need — evidenced, as Sinensky details, by God’s own displays of gevurah being acts that help those less fortunate.

V.

Without Gen. 14, the figure of Abraham would contribute nothing to the complexity of Sinensky’s discussion. Because, without Gen. 14, a very specific portrait of Abraham emerges. First and foremost, he is defined by his desire to escape difficult situations. He thus leaves Israel upon arrival due to a famine (Gen. 12:10), — a decision Nahmanides describes as “a great sin” in his comments on the verse[12] — prefers to divvy up his land rather than confront Lot and his shepherds (13:8-9) in an action instantly rejected by God (13:14-15),[13] and mistreats Hagar rather than reckon with the complexities of his tribal-familial dynamic (16:5-6, 21:10-14).[14]

Furthermore, Abraham displays a penchant for subterfuge in the face of violent confrontation. In contrast to the militarily mighty man capable of repelling a powerful alliance, Abraham twice prefers to mask Sarah’s identity — first in Egypt (12:11-13) and then in Gerar (20:1-2), with the latter being revealed as a diplomatic faux pas (ibid. 12:4-11). And though Abraham’s fears are real — “if the Egyptians see you and think ‘she is his wife,’ they will kill me” (12:12) — they are in sharp contrast to his actions in Gen. 14.

Finally — and noted by Grossman, as quoted earlier — Abraham is primarily portrayed as a man of moral virtue. He prays on behalf of the wicked people of Sodom (Gen. 18:23-33)[15] and is an exemplar of hospitality and kindness (18:2-8).

Without Gen. 14, Abraham is the paragon of certain moral virtues such as hospitality, kindness, and sensitivity, rather than physical conquest. But the inclusion of Gen. 14 complicates this depiction. Because for all that Abraham is everything mentioned above, Gen. 14 reveals him to also be a mighty, powerful leader capable of near-single-handedly repelling other mighty forces — in a story attested to by other nations and “borrowed” by the Torah. And his power is so great that all the other nations around him seek his friendship and recognize his dominance.

Gen. 14 thus positions Abraham as the human apotheosis of gevurah: he is someone who possesses tremendous physical prowess (even at an advanced age) — yet is not defined by it. Only when called on to defend his land and to redeem captives, does he respond in full force. His preference, however, is to display other moral qualities. In doing so, the Torah offers a perspective that, neither the rejection of strength or military might, nor any ambivalence towards it, but a recognition of it as a reluctant virtue.

Abraham the Hebrew thus provides a blueprint for his descendants. They must use their military strength to defend their land and redeem their families held in captivity — all the while desiring the opportunity to return to norms of hospitality and kindness.

[1] E. A. Speiser, The Anchor Bible: Genesis (Doubleday, NY: 1964), 99.

[2] Ibid., 105.

[3] Malbim to Genesis 14:1, s.v. “She’eilot.”

[4] Ha’ameik Davar to Genesis 14:1, s.v. “Amrafel.”

[5] It should be noted for the purpose of clarity that the translation into English no longer preserves the alphabetization.

[6] Nahum M. Sarna, The JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis (JPS, Philadelphia: 1989), 377–378. I should stress that this observation is restricted to the term ivri alone, as opposed to when it is combined with another term, such as in eved ivri, “Hebrew slave.”

[7] Jonathan Grossman, Abraham: The Story of a Journey (Maggid Books, Jerusalem: 2023), 44.

[8] Grossman, 49.

[9] Grossman, 54-58.

[10] Grossman, 61-68.

[11]https://thelehrhaus.com/scholarship/masculinity-and-the-hanukkah-hero-toward-a-new-interpretation-of-biblical-gevurah/.

[12] Ramban to Gen. 12:10, s.v. “va-yehi ra’av ba-aretz.”

[13] This is an episode of the Abraham story I hope to address at another time.

[14] This is an episode I have addressed previously on The Lehrhaus. See Mark Glass, “Avraham’s Test of Loyalty,” The Lehrhaus, Oct. 25, 2018, https://thelehrhaus.com/scholarship/avrahams-test-of-loyalty/.

[15] An episode I have addressed previously on The Lehrhaus. See Mark Glass, “Lot’s Wife Was Never Salt (And Why That Highlights the Greatness of Abraham)”, The Lehrhaus, Nov. 4, 2020, https://thelehrhaus.com/scholarship/lots-wife-was-never-salt-and-why-that-highlights-the-greatness-of-abraham/.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.