Jeffrey Saks

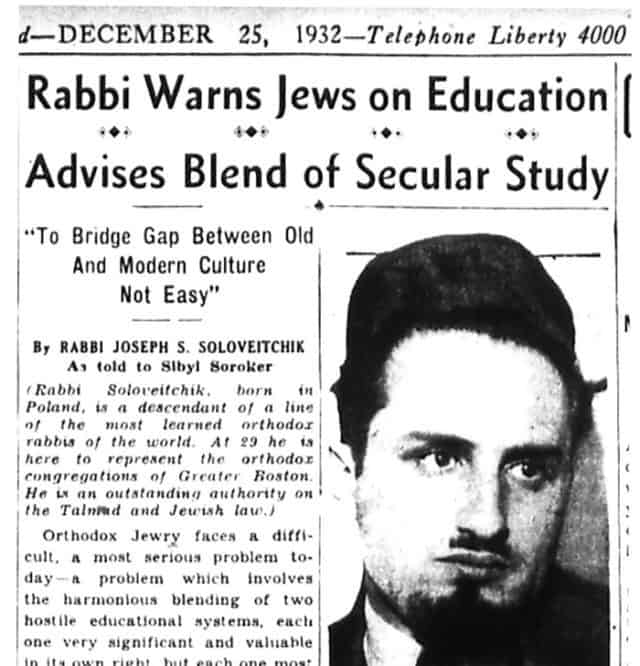

The appearance of a short article in a local Boston Sunday newspaper introducing the wider community to a new clergyman in town should not—in and of itself—be of significance for students of religious thought. The recent unearthing of the column will nevertheless interest readers of The Lehrhaus, not merely because the young rabbi in question is the 29-year-old Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, but because of the remarkable way in which he used the journalistic platform to communicate a vision for his leadership of Jewish Boston.

Yet, we would little note nor long remember the 800 word article, even with our fascination of all-things Soloveitchik, were it not for the fact that it contains the seeds of a religious and educational manifesto to which he would remain true for another half-century of public activity. His words reside at the intersection of his philosophical worldview and his educational vision and agenda.

The Text

Published a mere four months after his arrival in the United States, and a few weeks into his tenure as the Rabbi of the Boston Jewish community, we are amazed at the degree to which the Rav’s distinct voice is already discernible. Reading the newspaper clipping, we wonder how perfected the Rav’s English was at that point, rumors that he had mastered the language during the Atlantic crossing notwithstanding (he shares the by-line with the “as told to” interviewer)—but there is no doubt that the kerygma (to borrow one of his own favored words), the religious message being heralded, is uniquely his own. We can plot a straight line from the words in the Boston Sunday Advertiser from that Christmas morning over 84 years ago directly to his most significant philosophical writings of subsequent decades.

His statement was framed in the context of schoolchildren but it has broad implications for his larger worldview, and has bearing on what he later set out for adults and the community at-large. Between the lines, we glimpse the raw material of what we today view as the foundation stones of Torah u-Madda, Modern Orthodoxy, et al., although admittedly these were terms that the Rav never invoked himself, neither here nor elsewhere.

The interview’s focus on educational challenges facing the community was clearly deliberate (for the facts on the ground in 1930s Boston see Seth Farber’s contribution to this symposium and his excellent book). Facing a community of largely non-observant Orthodox Jews (an oxymoron by current parlance, but a sociological reality at the time), he was speaking to the parents of public school-educated Jewish children, with an eye on his plans to revamp the supplementary Jewish schools within a year, and—together with his wife—to launch New England’s first Jewish day school within five years.

With a bold plan most readers would likely have found surprising from the mouth of an Orthodox rabbi, the Rav identified the problem of Jewish education as the “collision between the old Jewish religious study and the modern scientific study.” While each one is “very significant and valuable in its own right” and both are “most essential to the spiritual make-up of the modern Jew,” the failures of Jewish education until that point were a result of the separation of the two by a “so-called Chinese wall.” When the two systems exist in conflict, naturally it is religious study which will suffer in the competition for time, energy, and resources. The Rav imagined a parity wherein the wall is torn down and each stands on its own, maintaining its own integrity, “coinciding,” with “neither one to suffer because of the other.”

The Implications

The most surprising turn comes when he critiqued, with what we presume to be disdain, the status quo: a type of exposure to Hebrew culture and Jewish literature, in which the curriculum has been neutered of the rough and tumble of classical Jewish learning, presumably for its perceived abstruseness, hair-splitting, and pushing elephants through needle eyes. In short, he attacked a learning system which had been guided by a need to generate “relevance.” The Rav charged it as being most irrelevant because it did not address the pressing issues. It could not provide a grand and dignified spiritual-intellectual experience capable of standing shoulder to shoulder with the secular studies so prized by an immigrant generation and its children.

Rabbi Soloveitchik’s “modernity” and “innovation” lay in his call to return to a more traditional curriculum; his plan was subversively conservative! The only Jewish learning that could hold its own side-by-side with physics and philosophy, literature and mathematics, was the intense study of what is called here “Talmud and the Jewish Law,” what he would go on in later writings to refer to colloquially as “Halakhah”—but using the term expansively, transcending the particular sense of ritual law, and developing a concept of traditional rabbinic study, as exemplified by the Talmud, as the authentic repository of Jewish thought.

Immersion in this subject matter, and not merely Bialik’s poetry, was the only object of study that will enable the youth to answer the question “What is Judaism?” Only the havayot de-Abaya ve-Rava and the “old Jewish laws” penetrate into the “inner soul of man and reward him with that deep spiritual feeling he cannot obtain” elsewhere. (The Rav was keenly aware that this does not happen automatically; that proper pedagogy was required; that his lack of concern with what passed as “relevant” did not mean he thought learning could succeed if it wasn’t engaging.)

Similarly significant is his en passant inclusion of girls as equal beneficiaries of his nascent educational plans. In describing the schooling of old, with the all-absorbing religious education of the “Cheder” in which “boys grew to full manhood,” there was nary a mention of young women, or if or how they received any education. (We know the answer.) But in presenting his picture for the future he aimed “to give our generation of growing boys and girls an all-embracing, well-balanced educational” experience. Knowing the ways that the continuation of his career would advance women’s Torah learning it is remarkable to see the germs of the ideas in place from the outset.

The Context

With these convictions in hand as he arrived in the United States it is easy to see how the Rav’s ideas were implemented—in the larger Boston community and his Maimonides School, at Yeshiva University, RIETS and their satellite communities and institutions (many of which were founded by the Rav’s disciples), and in his exercise of leadership in the larger American Orthodox community. But on the ideational level, we can see these seeds germinate in his later published philosophical writing.

The conclusion of Halakhic Man (1944) speaks of the freedom that his typological title character experiences through the act of intellectual creativity, the type of learning experience he was aiming at in 1932:

And halakhic man, whose voluntaristic nature we have established earlier, is, indeed, a free man. He creates an ideal world, renews his own being and transforms himself into a man of God, dreams about the complete realization of the Halakhah in the very core of the world, and looks forward to the kingdom of God ‘contracting’ itself and appearing in the midst of concrete and empirical reality.

What is this, if not a potential end result that can only be accomplished by the breaking down of the “Chinese wall” between Judaism and culture for which he had hoped!

Similarly, around the same time (although the reading public would have to wait 40 years for its publication), the Rav concluded The Halakhic Mind with a far more developed statement about the combination of Jewish thought and modernity—that the two are not in conflict—and that the encounter might promise a vivifying effect on Judaism itself:

The purpose of such an analysis is not to eliminate non-Jewish elements. Far from it, for the blend of Greek and Jewish thought has oftimes been truly magnificent. However, by tracing the Jewish trends comparing them to the non-Jewish we shall enrich our outlook and knowledge. Modern Jewish philosophy must be nurtured on the historical religious consciousness that has been projected onto a fixed objective screen. Out of the sources of Halakhah, a new world awaits formulation.

Two decades later, Rabbi Soloveitchik was still boldly confident, projecting strength of conviction and optimism in Halakhah itself to take its place alongside any other academic discipline. What he was telling the immigrant generation in 1930s Boston, and was repeating to their Americanized children and grandchildren in the 1960s, was that Judaism has nothing to fear from the secular realm. Writing in The Lonely Man of Faith (1965) he candidly admitted: “I have never been seriously troubled by the problem[s] of” evolution, Biblical criticism, psychology, or historical empiricism. When Rabbi Soloveitchik told his readers that these pillars of nineteenth and early twentieth century science and philosophy do not pose a contradiction to religious commitment or belief we readers never once think that he was undisturbed for lack of critically wrestling with these topics. Quite the contrary!

He goes on: “However, while theoretical oppositions and dichotomies [between Judaism and science or philosophy] have never tormented my thoughts, I could not shake off the disquieting feeling that the practical role of the man of faith within modern society is a very difficult, indeed, a paradoxical one.” Out of that torment he births the image of the Lonely Man of Faith—another typology which very well might have been the ideal product of the American Jewish education he was first beginning to imagine upon arrival in Boston.

The Vision

These aspirations for the flock he was leading were motivated by a sense that contemporary Jews “seek the spiritual combination, not [a] mechanical one.” The pressing issues of American Jewry are not merely resolving specific conflicts of how to manage as a committed Jew in modern America—although such conflicts were painfully real, especially the matter of Shabbat accommodation. But the Rav understood that even were all barriers to observance ameliorated, something our own generation has largely merited thanks to the leadership and vision of those that came before us, we would still be in need of a vision of how to develop an integrated religious personality and community. No matter how daunting his “altneu” curricular innovations may or may not have seemed at the time, history has now judged that they were indeed successful. However, it was specifically in this affective, “spiritual” realm that he maintained lifelong reservations, and even self-doubt. A 1960 essay “Al Ahavat Ha-Torah ve-Geulat Nefesh Ha-Dor” (“On the Love of Torah and Redemption of the Soul of Our Generation”; desperately still in need of an English translation), perhaps Rabbi Soloveitchik’s most personal piece of published writing, is an overlooked source in understanding the Rav’s educational philosophy. Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein called it “the single best introduction to the Rav’s thought” [see more on the essay’s content and background here].

In surveying the successes of religious education in America, the Rav confessed to three troubling phenomenon, almost three decades after his arrival:

First, the percentage of youths learning in yeshivot is very small. Even though it’s increasing every year, it is not yet sufficient to calm our worries. Second, we have not yet succeeded [in America] to produce true Gedolei Torah of whom we may be proud … [The third point constitutes] a serious educational-philosophical problem, which has long troubled me. Orthodox youth have discovered the Torah through scholastic forms of thought, intellectual contact, and cold logic. However, they have not merited to discover her [the Torah] through a living, heart-pounding, invigorating sense of perception. They know the Torah as an idea, but do not directly encounter her as a “reality,” perceptible to “taste, sight and touch.” Because many of them lack this “Torah-perception,” their world view (hashkafah) of Judaism becomes distorted… In one word, they are confounded on the pathways of Judaism, and this perplexity is the result of unsophisticated perspectives and experiences. Halakhah is two-sided … the first is intellectual, but ultimately it is experiential.

This fact, the spiritual and experiential deficiencies of American Orthodoxy, was a source of considerable frustration for the Rav—one which he described on a number of occasions. Rabbi Lichtenstein noted that this “frustration centered, primarily, on the sense that the full thrust of his total [effort] was often not sufficiently apprehended or appreciated; that by some, parts of his Torah were being digested and disseminated, but other essential ingredients were being relatively disregarded, if not distorted … [He often felt] that even among talmidim, some of his primary spiritual concerns were not so much rejected as ignored; indeed, that spirituality itself was being neglected … [T]he tension between the subjective and the objective, between action, thought, and experience, was a major lifelong concern. The sense that he was only partially successful in imparting this concern gnawed at him.”

We come after. We are the beneficiaries of the vision of so many that came before us. The preceding paragraphs to the contrary, it is of course idiotic to imagine that Rabbi Soloveitchik disembarked from the Mayflower at Ellis Island after having discovered America, carrying the two tablets of the law in his hand, single-handedly creating Orthodoxy in the New World ex nihilo. But if we live in a world where Judaism and modernity have been “coincided,” that phenomenon contains in its DNA traces of ideas articulated first by a 29-year-old rabbi, only weeks into his ministry.

And yet, if, nearing a quarter-century since his passing, we, too, recognize the spiritual shortcomings of our religious communities and spiritual selves, failures that haunted the Rav despite his herculean efforts and achievements, can we afford to be any less self-critical than he was himself?

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.