Shlomo Spivack (Translated by Levi Morrow)

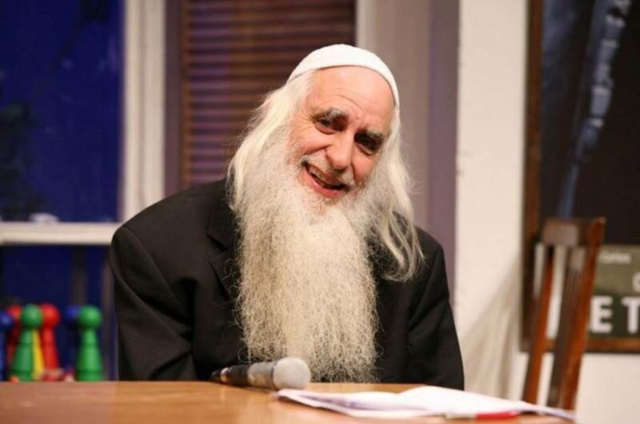

Rav Menachem Froman (1945-2013) was a man of ecstatic spirit, who strived to ensure that ideas from the realm of words, reached the realm of practice, reality, and action. This essay was written from the perspective of a student.

When we tell stories of tzaddikim, righteous people, we do so in an attempt to learn from their lives, lessons that should be primarily spiritual, as well as intellectual. Archetypically, the tzaddik is someone who finds spirituality in trivial things, in the seemingly meaningless expanses of life.[1] As the Hebrew Bible with its heroes and the Talmud with its sages, stories of contemporary tzaddikim must present all of their different facets and complexities; not angelic figures distant from reality, but human beings like us who lived meaningful, full lives.

Rav Froman was a Religious Zionist teacher, rosh yeshivah, and grass-roots peace activist. Anyone who met Rav Froman saw first and foremost a person praying. His prayer was always full of emotion, handwaving, exclamations, and song. In the manner of the Hasidim, it often seemed like Rav Froman was constantly going off alone and talking with his creator, seeking elevation. However, his prayer had another side to it as well, which many people might see as dry or formalistic. As opposed to many popular stereotypes about Hasidic prayer, Rav Froman paid strict attention to halakhic requirements ; Rav Froman was careful to pray with a minyan three times a day until his final days, and made sure to read each word from the siddur in front of him.

He himself described his careful attention to halakhic details as a struggle going on inside him, wherein his obligation to the fixed prayer framework defeated his commitment to spontaneous, personal prayer. He used to say that he considered it unequivocally more important to pray with a siddur, so that he would remember to say “Ya’aleh ve-Yavo,” than to give himself over to ecstatic prayer with his eyes closed.

Torah of the Roads

While Rav Froman’s unique way of praying became a dominant symbol of his personality, perhaps more central in his life was the actual study and teaching of Torah. This was certainly the center of our encounter with him as students. Rav Froman usually uttered a short prayer out loud before teaching Torah. I often hoped that he would recite a spiritual prayer, about connecting to the incredible power of the Torah, but it was always a request that the Torah we learned would affect the world of our everyday lives. Classic yeshivish approaches prioritize learning Torah for Torah’s sake, and mystics focus on affecting spiritual worlds, but Rav Froman believed learning Torah should primarily affect the rest of a person’s life.

He would start his lessons by dedicating the learning to a list of people who were sick, and then he would add a prayer for the success of soldiers in their missions or for the advancement of political matters. Sometimes he would add something along the lines of “The Torah should bring us closer to God,” or “God should illuminate our eyes with his Torah,” but the aim of most of the prayers was to orient the spiritual activity of learning Torah toward influencing the material world.

Rav Froman understood Torah study as a way of using any given moment to connect directly with God, but the study was always strongly connected to real life. He always made sure to learn Torah while traveling on the road, seeing Torah learnt on the road not just as a fulfilment of the halakhic requirements to learn Torah “when you walk on your way” (Deuteronomy 6:7), but as an expression of the dynamic nature of Torah. He noted that “Halakhah comes from a language of ‘walking,’” and so you have to “walk with the Torah.”

Rav Froman believed that learning Torah on the road creates a dynamic connection between the Torah above and life below. Many passages in the Zohar recount conversations and ideas discussed by the sages of the Zohar while they were walking on the road. Moreover, the greatest mysteries of the Zohar were revealed specifically by people the sages came across during their travels, seemingly simple individuals, like the old grandfather or the donkey driver. Rav Froman identified the Zohar as Torah of the Land of Israel because it is learned on the road, as opposed to Torah of the Exile which is learned in yeshivah, in a static manner. Classic yeshivah study involves cycling through the same texts year after year, each student sitting in their “set place” within the four walls of the beit midrash. The Torah of the Land of Israel is studied throughout the valleys and vistas of the land, where surprises abound.

A Radiant New Zohar in Torah Study

In his classes, there was a clear divide between the students who were seeking elevation and transcendence, and Rav Froman,who was constantly pulling them back down to earth. “Zohar Hadash,” was the rabbi’s favorite term for someone who shared deep ideas or wondrous thoughts that were insufficiently rooted in the actual words of text they were learning (the phrase literally means “new Zohar,” but plays on the name of the latest layer of the Zoharic corpus). Whenever he studied any Torah text, and the Zohar most of all, Rav Froman would first and foremost attempt to understand the words of the text. Only later would he attempt to determine what relevance it has for our lives, what its existential meaning might be. This second stage was the goal of the learning, and when they would finally reach it, Rav Froman would remark in an intentional Ashkenazi accent “ha-Ikker le-Mayseh,” “the main practical point,” a reference to Rebbe Nahman of Bratlsav. However, this teaching always had to be based on the learning uncovered in the first stage.

For a time, the Zohar classes that Rav Froman taught in his house began at 3:30 AM and went until sunrise. In one class, a new student came expecting to hear wondrous ideas. He got up at midnight, immersed himself in a mikvah, and arrived at the class positively shaking with awe and excitement. The class began, and after reading one line of the Zohar, Rav Froman wanted to look in-depth into one of the verses cited by the Zohar. As he always did in such scenarios, Rav Froman opened up a concordance, and he proceeded to spend 45 minutes researching the philological meaning of one of the words. The student’s face showed just how distant this was from the experience he had been expecting.

This helped me to fully understand Rav Froman’s approach to Torah study: his philological precision was a means to reaching the deeper meaning of the words. He once explained this to be the deep meaning of the unity of Kudsha Brikh Hu and the Shekhinah: The Shekhinah is the earth, the lowest of the sefirot, which according to the Zohar “has nothing of her own.” In the process of Torah study, she manifests as the need for the student to “justify themselves textually,” as Rav Froman put it. The attribute of Kudsha Brikh Hu is the divine attribute associated with heaven rather than earth, and it manifests as the student’s freedom to seek spirituality and meaning. Only when solidly grounded in the precise meaning of the words can the student seek out the spiritual expanses contained within the text. Connecting these two traits leads to the truest understanding of and connection to the Torah. In this way, spiritual meaning is anchored in the meaning of the words themselves, rather than read baselessly into the text. Bringing together Kudsha Brikh Hu and the Shekhinah, creating an inner-divine unity, is achieved through holding together the seemingly opposite poles of textual fidelity and the quest for meaning and relevance.

I merited to experience Rav Froman’s approach to Torah study in its clearest form in the study of the Talmud. When I organized Rav Froman’s Talmud class in Yeshivat Tekoa, I asked him how I should advertise the class. “Talmud study focusing on omek ha-pshat, the depths of the straightforward meaning,” he said, paraphrasing Rashbam. In choosing this expression, Rav Froman combined “depth,” which grants intellectual freedom, and “straightforward meaning,” which expresses the reader’s obligation to the text.

In the 2007-2008 Shemitah year, we studied Tractate Shevi’it from the Jerusalem Talmud together. Rav Froman was very excited to use the critical, academic commentary of Professor Yehuda Felix, because it was based on extensive research into the agronomic realities of the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods. Indeed, Rav Froman loved using the Steinzaltz edition of the Talmud for the very same reason, because it contains marginal notes with scientific and historical details relevant to the Talmudic discussion. After several months of studying Shevi’it, during which time Rav Froman spent a lot of time delving into footnotes, we got stuck on one section, going over it again and again while Rav Froman remained unsatisfied with our understanding of it. “I am having trouble understanding the agronomic reality of that time,” he said,” and that is why I cannot understand the Talmud.” After several weeks, I tried to subtly hint to him that we were not really making any progress and perhaps it was time to move on. He agreed, and deliberated about what to do while flipping forward through the pages. He pointed out that in just a few pages there was a section he thought was very important for us to learn, but, as he said, “However, skipping seems wrong from the perspective of service of God!”

Rav Froman would “walk around with Torah teachings,” another expression borrowed from Bratslav teachings. This meant that he would always seek out texts that were connected to his daily life and the life of the nation, which would enable him to delve deeper into ongoing events. For example, during the Disengagement, or when there were terror attacks, he would learn Torah that he felt spoke to those events. This approach reached its crescendo when Rav Froman was ill; he chose to learn the Zohar on the Torah portion of Vayehi for months on end, specifically because it discusses death.

However, it is worth reiterating how central Halakhah was in Rav Froman’s life. His Shabbat meals always began with a Halakhah learned from the Mishnah or some other book of Halakhah, like the Arukh Ha-Shulhan. As one of his sons notes, Rav Froman would often read Rambam’s Mishneh Torah aloud to everyone at yeshivah meals, and he once read it aloud to the entire bus for an entire trip from Otniel to Haifa and back (Hasidim Tzohakim Mizeh §12). “The Hebrew word ’halakhah’ derives from ‘halikhah,’ going, so it must always be our starting point,” he would say. He always insisted that Torah be relevant to life, but his life always started from Halakhah.

A ‘Rav Kook’ for Islam

Rav Froman was a pioneer in the realm of grassroots interfaith dialogue in Israel. He believed that dialogue and understanding held the keys to solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He also did not shy away from writing essays critical of every sector of Israeli society, particularly when it came to issues around peace and the land (see the collected volume Sohaki Aretz, cited below). Consistent with his insistence that Torah affect practical life, Rav Froman never cordoned political matters off from the rest of his life entirely. These matters were present in the background of almost every daily encounter with him. However, as his students, we did not hear much about them. He never discussed them directly, and he certainly did not let these topics take over his classes. If he mentioned politics at all in a class, it was only to relate some relevant anecdote.

In 2014, a collection of Rav Froman’s essays called “Sohaki Aretz” was published, containing a glimpse into his intense involvement in social and political issues in Israel. The book displays the rabbi’s responses to different matters, his clear perception, and his ability to foresee how things would turn out. A few lines from one of the essays indicate the balanced place that politics had in Rav Froman’s life:

Recently, after one of my classes, a young woman approached me, visibly agitated. With great emotion, she asked me, “How does the rabbi think we should solve the problem of Judea and Samaria?” I will be so bold as to tell you what occurred to me then. I wanted to say to her, “Perhaps instead of being so agitated about the question of Judea and Samaria, it would be better to think about how to love your husband, about how to raise your children.”

Later in the same text, Rav Froman is even more direct:

Ultimately, the place we give politics in our lives must be realistic. We are forbidden from allowing politics–with the dynamic skill of all superficial matters–to override and take over our lives, making them superficial and alienated. (Sohaki Aretz, 38-39)

As part of his faith-based peace efforts, Rav Froman met with Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the founder and spiritual leader of Hamas, who was in prison at the time. After studying religion and Koran together, they built a lasting relationship of mutual respect, which allowed Rav Froman access and safety in his occasional visits to PA controlled cities. Rav Froman loved to quote something Sheikh Ahmed Yassin told him during one of their meetings: “Honorable Rabbi Menachem, you and I could make peace in five minutes. However, the problem is not you and I, but your government!” Sometimes Rav Froman would add, “Let’s not delude ourselves, making peace would take us five hundred years, not five minutes!” He didn’t mean that it’s impossible to make peace, but the reverse: it’s possible to make real peace, but real peace is a long process.

Once he said

I hope that Islam will merit a ‘Rav Kook’ of its own, someone who will sublimate the religion, redeeming it from the primitivity and harsh violence that exists in the Quran. He would make it an ethical religion seeking peace on the most global level.

Rav Froman recognized the power of the Islamic religion, but did not deny that it also had negative, even violent, aspects. The spiritual basis of his peace activism, as he taught through the mediums of the Zohar and Rebbe Nahman, was the unifying of opposites between right and left, between good and evil. They believe in recognizing the place of evil (which, according to Kabbalah, issues from the left side of divinity) in the world and trying to turn the bitter into the sweet, which is the highest goal of the mystical teachings of Torah. His political positions were founded on a deep understanding that we need to imitate God and his actions. He often expressed this in noting that “Shalom/Salam,” meaning “Peace,” is one of God’s names in both Hebrew and Arabic. “It’s the most beautiful of his names,” Rav Froman would say, quoting from his Muslim friends.

Peace with the Neighbors

Many people, including people with whom he had helped establish Gush Emunim, criticized Rav Froman’s peace activism as naively idealistic. His opponents saw him as at best delusional, and at worst as someone who hangs out with murderers. Once, one of these critics even pulled a gun on Rav Froman in the middle of kabbalat shabbat! However, Rav Froman actually based his activism specifically on a realistic understanding of the world. He would examine reality directly and study it well, always examining it thoroughly before drawing conclusions. Rav Froman was familiar with the Palestinian citizenry, with the leadership, as well as with the meaning and role of Islam, going back to the beginning of the conflict.

“On the day we went up to Sebastia (outside Nablus),” Rav Froman recalled after thirty years, “I told Hanan Porat (the leader of the settlement movement in Judea and Samaria at the time) that we needed to start making peace with our neighbors, because if we didn’t, we would not survive here for long.” Finding religious and spiritual common ground was, as Rav Froman saw it, the only realistic possibility for advancing Israel’s complex relationship with the Palestinians and creating peace. If you look closely at his activism, if you look at the articles he published in newspapers or at videos documenting his meetings, you can see that Rav Froman managed to penetrate the fundamental barrier between the two nations and reached the level where, potentially, there could be a true connection and even peace between the two nations. It seems to me that many times Rav Froman moved beyond the level of potential and succeeded in advancing true peace. There were also times, however, when Rav Froman perhaps failed to make this possibility that he saw into reality.

He once threw out a sharp generalization, meant perhaps to highlight the matter’s importance:

If you think Maimonides studied philosophy because he loved it, or that Rav Kook was involved with the secular world because he connected with the ideas, you are mistaken. They were both involved in the external world because they understood that it is reality and that God is there, so it is exactly there that you must find God. It may seem like a place distant from God, but it is exactly there that you have to shine the light of God’s existence.

Paraphrasing Rav Froman, I might say that he was not involved in peace activism because he enjoyed it, but because he understood that, in our reality today, it is specifically there that we must find God.

Applying the Attribute of Malkhut

At Rav Froman’s first yartzheit, we gathered together – his family, friends, and students – at his grave in Tekoa. Standing by his grave, his wife, Hadassah, said something that has stayed with me ever since. Hadassah read, line by line, the epitaph Rav Froman himself wrote for his tombstone:

Tried to run to Rabbeinu / And to dip in the radiance of the holy lamp / to follow in the footsteps of Ha-Rav / The people of your nation are all righteous, they will forever inherit the land.

This is how Hadassah explained the lines, while addressing Rav Froman in the first person:

You wrote here the milestones of your life’s journey, a journey through the great tzadikkim to whom you alluded – Rebbe Nahman, Rabbi Shimon Bar Yohai, and Rav Kook. However, your whole journey always led you to the last line, to the people and to the land. You could have chosen a different motto, also from the Zohar: “The enlightened will shine with the radiance of the firmament.” You could have easily connected the radiance of the firmament with constantly ascending, up and up, throughout your life, but you always chose to bring everything down to earth.

When I told Hadassah that I wanted to write an essay about Rav Froman based on this element of his personality, I told her that I wanted to call it “The Non-Spiritual Character of Rav Froman.” She agreed with my description but said that I should call it “The Anti-Spiritual Character” of Rav Froman, because he wasn’t non-spiritual, rather he actively opposed what other people call “spirituality.”

I spoke with Rabbi Dov Zinger, an early student of Rav Froman and Israeli educator, who advised that I sharpen the point even further. In his opinion, Rav Froman was naturally inclined to focus “above,” and had to force himself to connect to us, down below. He chased after reality because he believed in it. His spirituality was realistic, and his reality was spiritual.

I cannot say if Rav Froman descended from above more than he climbed up from below, but I am certain that he was constantly moving between those two poles, in unending tension. Regardless of which was more dominant, I see here a project that we can take up from Rav Froman and continue forward in our lives. We must create an uncompromising integration between ascending above and holding tight below, between running after the greatest, most hidden teachings and constantly trying to realize them in reality.

This is what it means to apply the attribute of Malkhut, which Rav Froman saw as the critical center of the Zohar’s secret teachings. Malkhut, the lowest (or last) of the sefirot, is also called “Land,” because it connects the loftiest secrets to the earth, to the ground, in that it is the final stage in the descent of God’s influence to earth. This is the integration of the greater land of Israel and peace, between prayer and Torah. Rav Froman began this integration, and we can continue it.

[1] [Translator’s note- This might more typically be framed as “raising up the sparks” of divinity scattered throughout the mundane, even profane, world. The ability to find divinity in moments, spaces, and actions seemingly empty of it represents a key mode of Kabbalistic and Hasidic engagement with the world. See, for example, Rabbi Isaac Luria, Sefer ha-Likkutim (Jerusalem: 1988), 239-240; Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezritch, Maggid Devarav le-Ya’akov, ed. Rivkah Schatz-Oppenheimer (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1990), 24, §9. This was also what Rav Kook was doing when he identified both secular Zionism and bodily healthcare as forms of religious piety, holiness, and devotion. See Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, Orot, (Jerusalem: Mossad HaRav Kook, 1963), 70–72, Orot ha-Teḥiyah §18; 80, Orot ha-Teḥiyah §33-34. –LM]

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.