Leslie Ginsparg Klein

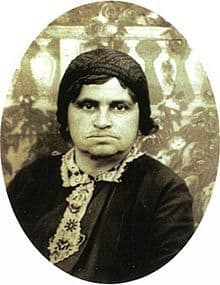

In the Orthodox community, Sarah Schenirer has been valued as an example of how to appropriately enact change. There’s good reason for this. The founder of Bais Yaakov created a movement for mass Jewish education for girls. She normalized the concept that girls should receive a formal Jewish education. It was one the greatest innovations of the past century, and certainly the most successful with regards to women in Judaism. She effected change by balancing tradition and innovation. She remained steadfastly committed to her Orthodox community, even as she pushed boundaries.

Recent popular accounts tend to rehearse a particular aspect of Bais Yaakov’s founding: the notion that Sarah Schenirer first secured the approval of the major gedolim of her time—the most remarkable was the Hafetz Hayyim—before launching her grassroots educational movement in 1917 to effect change. Some argue that she secured this approbation even before beginning the foundational work for the movement in 1915. This is the sort of thing stated by Rabbi Hanoch Teller, in his Builders. Rabbi Teller wrote that Schenirer “knew what she wanted to do, but felt that she must first obtain rabbinic approval for her project.” Therefore, she obtained the approval of gedolim including the Hafetz Hayyim, the Gerrer Rebbe and Rabbi Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski. He writes, “Having obtained the blessing of such prominent gedolim, Sarah was ready to begin her work.”

However, there is something problematic about this account. Juxtaposed to his narrative is the reproduction of the Hafetz Hayyim’s letter in support of Bais Yaakov. Dated 1933, this document was written 16 years after Sarah Schenirer opened the first Bais Yaakov school in Krakow. In fact, the Gerrer Rebbe’s and Rabbi Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski’s support of Schenirer’s efforts were likewise issued a number of years after she had established the Krakow school. The only exception was the Belzer Rebbe, who gave Sarah Schenirer a verbal blessing for her future labors. The incorrect chronologies of these narratives obscure elements of Sarah Schenirer’s true greatness and her valuable legacy to our community today.

Rabbi Teller’s account is not the only account that presents an inaccurate chronology. Consider, as well, Rabbi Avrohom Birnbaum’s brief history printed in the popular Bais Yaakov Cookbook: “She began petitioning gedolei Yisroel, some of whom were very sympathetic and encouraging. Armed with the brachos of Rav Yissochor Dov, the Belzer Rebbe, the Chofetz Chaim, the Gerer Rebbe, the Imrei Emes she forged ahead.” Once Schenirer secured this rabbinic approval, “her dream began to materialize.” Similarly, Rabbi Paysach Krohn relates the following in a video commemorating Sarah Schenirer’s eightieth yahrzeit:

She wanted to start a religious school for girls, but many were opposed to her idea. Her own brother was against it. She had a brother in Czechoslovakia and she wrote him. She said, “Why don’t we ask the Belzer Rebbe? Let’s see what he says about teaching Torah and giving frum education to girls.” And her brother said, “Ok, let’s go to Marienbad. That’s where the Belzer Rebbe is.” And in Marienbad, they sent in a kvittel to the rebbe … And Sarah Schneirer wrote in her diary, she was in the room when the Rebbe said these words: Brakhah ve-hatzlakhah … And she went, and she had this same question asked to the Chofetz Chaim, and to Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski. They were the leaders of Klal Yisroel and both of them agreed that now was the time to teach Jewish girls Torah … and to start these schools. Finally, they decided to go to the Imrei Emes [Gerrer Rebbe] … He too consented and said it was the right thing to do at this time. Now, she was energized. Now, she was not going to be stopped. She never went back to sewing again. Now, her mind and her heart were set on teaching girls Torah.

In addition to all of these gedolim, Rabbi Teller mentions that Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin and Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, also offered approval of Schenirer’s efforts. He presents these approbations, along with the others, as having preceded Schenirer’s work. Rabbi Teller states, “With the blessings of gedolim, and the support of the leaders of her community, Sarah was ready to set up shop.”

The idea that Schenirer had full rabbinic and communal support when she started Bais Yaakov is not only ahistorical, but it diminishes her achievement. These narratives contradict Schenirer’s own diary and memoir, which are both published and readily available. Her writings, as well as many accurate biographies, reveal her tremendous accomplishments. Put simply: the greatness of Sarah Schenirer is that she persisted in doing what she knew was right despite communal opposition and apathy.

Schenirer’s Biography

Sarah Schenirer was born in Krakow, Poland, in 1883 to a family of Belzer hassidim. As she grew up, she watched her contemporaries—frum girls like her, from hassidic families like hers—assimilate at an alarming rate. Schenirer concluded that without a strong Jewish education and environment providing a grounding in tradition, girls had nothing to mediate the secular influences and ideologies they were encountering in the Polish state schools they attended. While Schenirer deeply wanted to work with girls and be a catalyst for change in her community, she did not see how that could be possible.

That changed when she was exposed to the ideology of Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch. During World War I, Schenirer escaped to Vienna. There, she attended the shul of a Neo-Orthodox rabbi, Rabbi Dr. Moshe Flesch, whose sermons inspired her. On Shabbat Hanukkah, for example, he spoke of the heroine, Yehudith, using the moment to implore his female listeners to follow in the path of Yehudith and take heroic action. Schenirer was taken both with his message and with the style of his sermon. A rabbi directly addressing women from the pulpit was something that did not happen in Krakow synagogues. Schenirer came to believe that if she could teach the girls of Krakow what she was learning in Vienna, they would surely be similarly inspired. Schenirer determined to answer this call and devote herself to saving Jewish girls through education.

Biographies get it right to this point. It’s after Schenirer’s epiphany that the narrative sometimes unravels. As she wrote in her memoirs, Schenirer returned to Krakow toward the end of the war and immediately got to work on her Jewish education project, building support and organizing planning meetings.

Schenirer gathered a group of older girls to teach them. However, she found them unreceptive. They ridiculed her and mocked her for being too frum. But Schenirer didn’t give up. She determined that she would be more successful reaching young girls who had not yet been exposed to the ideological influences of the secular world. She decided to start a school for young girls that would teach limudei kodesh.

But in Poland, Jewish education for girls was a contested issue, with the rabbinic and communal establishment remaining firmly against it. It was considered to be against Jewish tradition, if not outright forbidden by halakhah. In fact, in 1903, at a rabbinical conference in Krakow, one rabbi suggested establishing schools for girls. He stated that his colleagues had neglected girls’ education and that Jewish schools for girls could stem the frightening rates of assimilation plaguing the community. However, he was shot down, and the convention instead declared that fathers should certainly educate their daughters, but to establish Jewish schools for girls would be wrong. Others would try as well to fix girls’ education, but none gained the traction to be successful.

Schenirer wrote to her brother about her ideas, a correspondence that led to her famous meeting with the leader of her family’s hassidic sect, the Belzer Rebbe. Her brother expressed concern that Schenirer was getting involved in something too political and suggested that they approach the Belzer Rebbe for his advice. It cannot be stressed enough that the only primary source for this meeting is Sarah Schenirer’s own memoir, published in a Bais Yaakov publication. She writes as follows:

I could not get my dream of establishing a religious school for girls out of my head. At first [my brother] laughed at me. “Why do you want to start busying yourself with political parties?” he wrote back. But when I answered him that I was firmly resolved not to abandon this mission, he wrote me: “Nu, let us go to Marienbad where the Belzer Rav is now, and we will hear whether the tzaddik of the generation agrees to it.” There was no end to my joy. Although I did not have much money, I hurriedly prepared myself for the trip. When I arrived in Marienbad, I and my brother went immediately to the Belzer Rav. My brother, who was a ben bayis there, wrote in his kvittel: “She wants to educate Jewish daughters in the Jewish derech,” and I heard the answer from the tzaddik’s holy mouth myself: Bracha v’hatzlacha. The words were like the most expensive balsam oil, instilling fresh courage in my limbs. The blessing from the great tzaddik gave me the best hope that my strivings would be fulfilled.

Immediately after this event, Sarah Schenirer writes about starting her first school. She did not consult with any other rabbis before opening the school.

The True Chronology of Rabbinic Approbation

Histories of Sarah Schenirer written by men or women connected to the movement, as well as those written before 2000, consistently present an accurate chronology. Most do not even discuss the movement’s later rabbinic approval, as these authors have no implicit question of the propriety of Bais Yaakov. One example of an accurate narrative is Joseph Friedenson’s 1982 biographical sketch of Schenirer, written along with Chaim Shapiro, which appears in the ArtScroll book, The Torah World. Friedenson was the son of Eliezer Gershon Friedenson, an Agudath Israel leader who served as the editor of the Bais Yaakov Journal in Europe. Their account follows that of Schenirer’s memoir:

She wrote about her undertaking to her brother—a Belzer Chassid living in Czechoslovakia. At first he ridiculed her. But when she insisted that nothing would stop her, he invited her to come to Marienbad: “The Belzer Rebbe is here and we shall ask him.” She invested her last pennies in the trip. Her brother wrote a note (a tzettel) to the Rebbe: “My sister wants to educate Bnos Yisrael in the spirit of Yahadus and Torah,” to which the Rebbe replied “Beracha Ve’Hatzlacha” (Blessings and Success)! These two words gave her all the impetus she needed. And one might add that, at the time, this was the only help she received” (emphasis in original).

Friedenson and Shapiro stress that Schenirer did not have any rabbinic support beyond that of the Belzer Rebbe when she started Bais Yaakov. She certainly did not have widespread approval; she faced serious opposition. Even the Belzer Rebbe did not extend his full approval to Bais Yaakov as he did not permit the daughters of Belzer families to attend. Friedenson and Shapiro write that later, Friedenson’s father, along with other Agudath Israel leaders “stormed all the ivory towers of rabbinical leadership” and secured rabbinic approval for Bais Yaakov. As they explain, “She did not have to fight Reform or Conservative rabbis. She had to overcome the opposition of Orthodox leaders.” Friedenson and Shapiro present a very different account than the recent narratives, both in terms of who suggested meeting the Belzer Rebbe, who obtained the additional rabbinic approbations and when.

It is clear that the leadership and the masses did not initially support Sarah Schenirer. In an essay reprinted by Bais Yaakov, Rabbi Yehudah Leib Orlean, Schenirer’s successor as leader of the Bais Yaakov movement, wrote the following about her challenging experiences:

The matzav of chinuch habanos that Sarah Schenirer encountered in Poland was like a rocky, uncultivated field. Although she was about to attempt something that had never been done before, that had no model in our Mesorah, she knew it was crucial. And so she began to build from scratch, transforming her movement from its modest beginnings to a powerful empire … the people she turned to for assistance, especially in the beginning, turned her away. They had no idea what was happening in the streets. They had no concept of the catastrophe befalling our nation. But Sarah Schenirer was determined, and again and again she persuaded, cajoled, explained and clarified, awakening the slumbering leaders from their blissful dreams and begging them to accept the only solution that could divert disaster.

What changed and ultimately garnered Bais Yaakov rabbinic and communal approval was the movement’s success. Sarah Schenirer’s first school grew from 25 students to 40 within a few months and other towns began petitioning Schenirer for help replicating her school in their locations. Her accomplishments caught the attention of the local Agudath Israel branch in 1919, which lent support to the fledgling school. In 1924, the national Agudath Israel adopted the Bais Yaakov school system, accepting fiduciary responsibility. Founded by adherents of Rabbi Hirsch, Agudath Israel sought to improve education in Eastern Europe, including how girls were educated. Additionally, Agudath Israel was a political party within the Polish parliament and wished to court the vote of women, who had been awarded the right to vote in 1918.

When Agudath Israel adopted Bais Yaakov as their own project, it threw its financial and organizational resources behind it. Agudath Israel leaders believed that in order to expand Bais Yaakov internationally, which was their intent, they would need additional haskamot, rabbinic statements of support, and they went about soliciting those statements. Indeed, the Bais Yaakov Journal and other movement publications regularly published the letters of approbation that Agudath Israel secured in order to silence the critics of Bais Yaakov, the very letters referred to by Rabbis Birnbaum, Krohn, and Teller.

Agudath Israel did not petition gedolim because its leaders questioned the halakhic permissibility of educating girls, as they were already involved in the endeavor. Rather, Agudath Israel’s solicitations were a strategic way to fight the opposition and garner financial and ideological support. For instance, a fundraising journal published in 1928-1929 included the letters of support from the Gerrer Rebbe and Rabbi Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski. Another letter from the Gerrer Rebbe is dated 1929. The Lubavitcher Rebbe wrote in 1934. Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin, a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudath Israel in Israel, wrote in 1941, six years after Sarah Schenirer’s death.

A Source of Confusion

The most famous response is that of the Hafetz Hayyim, written in 1933. Agudath Israel solicited that letter because of the rabbi of the town of Frysztak. He had refused to allow Bais Yaakov to open a school in his town. When a frustrated colleague of Schenirer wrote to her about the rabbinic opposition she was facing in opening a school in another town, Schenirer replied,

If the local Rav will not support you, you will not make it. Most interesting; we had the same trouble with his brother in another city [Frysztak]. He, too, opposed our school. The Agudah wrote to the Chofetz Chaim, and his reply will soon be published in our magazine, number 106. In that city we lost seventy girls to the other [Haskalah] schools. We were too late (The Torah World, 169).

Schenirer never claimed to have contacted the Hafetz Hayyim directly. Rather, she herself indicates that Agudath Israel contacted him well over a decade after the founding of Bais Yaakov. Indeed, the Hafetz Hayyim’s letter in support of Bais Yaakov is addressed to the Jews of Frysztak.

Some have confused this letter with the Hafetz Hayyim’s footnote in Likutei Halakhot Sota 21b, where he encourages Torah study for women, and have quoted the footnote as having been written as support for Bais Yaakov. However, this volume of Likutei Halakhot was published in 1911, several years before Sarah Schenirer founded Bais Yaakov. While Bais Yaakov made use of this statement as support, it was certainly not written with Bais Yaakov in mind and may not have referred to formal schooling at all. It certainly does not mention Bais Yaakov or formal schooling, as the 1933 letter does.

Further the Hafetz Hayyim wrote this comment in a footnote. If he had meant this to be a major declaration or a significant policy shift, one would assume he would have featured it more prominently. Indeed, the footnote was not considered to be a true approbation of Bais Yaakov, because Agudath Israel needed to ask the Hafetz Hayyim for an explicit letter of support to quell the opposition in Frysztak.

Even the Hafetz Hayyim’s formal support did not end the movement’s struggle for legitimacy. Rabbi Orlean wrote after Schenirer’s death in 1935, “Still, even once she had achieved her hard-earned acknowledgement among the majority of the population, there remained individuals who would not capitulate, and continued to place obstacles in her path. They used every means at their disposal to restrain the movement and limit its scope. Even as the schools flourished, the struggle continued.”

In 1938, five years after the Hafetz Hayyim’s letter, Rabbi Aharon Volkin, a prominent posek, wrote a responsum (Zaken Aharon, vol. II, no. 66) regarding Bais Yaakov. After discussing his reservations about the permissibility of teaching girls Torah, he concludes, “being that we have drunk from the waters of salvation, that thousands of souls of daughters of Israel have been saved by these schools, and we will cast aspersions?” The success of Sarah Schenirer’s work was the factor that ultimately succeeded in changing the opinions of rabbis and leaders on girls education.

Sarah Schenirer’s True Legacy

Why have Orthodox biographers rewritten the story of Sarah Schenirer and the founding of Bais Yaakov in recent years? Every society remembers its history in a way that promotes and fits in with its contemporary values. In today’s Yeshivish community, there is a stress on the importance of consulting gedolim, and great trepidation towards change, particularly with any issues related to women. Therefore, Sarah Schenirer, a woman who started a revolutionary innovation for women, albeit for traditional reasons, could be viewed as an incredibly threatening figure. Framing the founding of Bais Yaakov as having taken place with mass rabbinic pre-approval, removes the tension and fits the story squarely into contemporary Yeshivish values.

It is important to stress that there is no evidence to suggest that Sarah Schenirer was trying to sidestep rabbis. In fact there is evidence to support that idea that Schenirer considered rabbinic support very important, especially when establishing schools in new locations. However, she simply did not speak to all the gedolim these narratives list besides the Belzer Rebbe, before starting Bais Yaakov. Nor is there any evidence to suggest that she thought it necessary at that time.

This historical disconnect has consequences for today. Advocates for change, particularly related to women, are often challenged with the criticism that they are abandoning the example of Sarah Schenirer, because these critics claim Schenirer refrained from any action until she had consulted with the Hafetz Hayyim and the other rabbinic leaders. The desire to seek the approval of multiple gedolim before suggesting or implementing even the smallest change or starting any kind of community organization or initiative is a valid approach. However, Sarah Schenirer is not representative of this approach. To claim Schenirer personifies this approach or to use her to criticize or undercut the efforts of those who are truly following her approach to innovation and positive change, is simply wrong. Instead, it effectively squelches new, positive calls for improvement and innovation.

Before the founding of Bais Yaakov, Orthodox leaders and newspapers discussed and debated the issue of girls’ education. The community was waiting for a change to come from above, from the leadership. Schenirer was not the first to suggest starting schools for girls, but instead of talking or waiting, Schenirer took action. She started on a grassroots level, from the ground up. Schenirer approached the rabbi with whom she had a connection for guidance, and she went about the work that she knew at her very core needed to be done to save the women of Klal Yisrael. And that is why history remembers her name, while so many of the leaders and detractors have fallen into obscurity.

The true legacy of Sarah Schenirer is that one person can make an incredibly positive change. Her legacy is the power of grassroots efforts. It is persisting in the face of apathy, ignorance and opposition. It is the belief that if one’s work is truly for the benefit of the community, it will be successful. As Schenirer herself wrote, reflecting back on the movement’s inception, “if the intent is sincere and the aim is proper, my goal will certainly be achieved.”

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.