Yosef Lindell

Although the practice is not without its detractors (see Rambam’s classic responsum), it is common practice to stand during the public reading of the Ten Commandments, or Aseret ha-Dibrot.

This popular minhag notwithstanding, the degree of prominence that should be attributed to the Ten Commandments has long been a subject of controversy. Although the Mishnah (Tamid 5:1) states that the Aseret ha-Dibrot were recited every day in the Temple, this practice was later abolished because of “claims of heretics,” who, according to the Yerushalmi in Berakhot (9b), asserted that “these [commandments] alone were given to Moses at Sinai.” The heretics’ identity is a point of contention among scholars, but it is clear that the Sages were concerned that people were assigning undue stature to these ten dibrot and the many mitzvot they contain.[1]

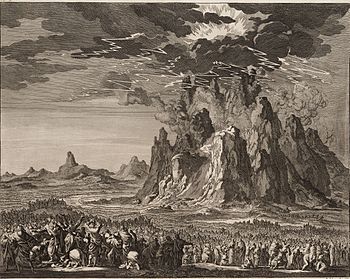

Scholars have also theorized that the very term Aseret ha-Dibrot, which is different than the language “Aseret ha-Devarim” used in the Torah (Devarim 4:13, 10:4), was invented by the Sages to dispel any notion that these are the most important commandments. Aseret ha-devarim literally means “ten statements,” but can also be understood as ten commandments; perhaps, one might erroneously think, uniquely important commandments. Dibrot, on the other hand, is not the plural of davar, a thing, but of diber, speech. What is more, diber, which appears only once in Tanakh as a noun, connotes not just any kind of speech, but specifically revelatory speech. When Yirmiyahu contends that the words of the false prophets have not been revealed to them by God, he protests that “ve-hadiber (and the word) [of God] is not in them” (Yirmiyahu 5:13). Thus, the Aseret ha-Dibrot are “ten divine utterances” that were spoken by God to the Children of Israel as part of the revelatory experience at Sinai. Unlike the other mitzvot, God revealed them to all of Israel in a transcendental encounter.

There is no doubt that the mitzvot contained in the Aseret ha-Dibrot are important. It is for this reason that God chose to reveal them, and not any other statements, to the entire nation. Yet there remains a danger that the Sinai experience might make them appear overly important. Perhaps that is why the Sages chose to use the term dibrot instead of devarim: to emphasize that their uniqueness lies primarily not in their content, but in the manner in which they were transmitted. They are central principles of the Torah, and that is why they were revealed, but their unique status ought not to diminish the need to observe the other commandments.

Moreover, a close reading of a talmudic discussion toward the end of Makkot (23b-24a) supports the contention that the Sages intentionally avoided emphasizing the importance of the commandments in the Aseret ha-Dibrot, instead focusing on their unique manner of transmission:

R. Simlai preached: “Six hundred thirteen precepts were communicated to Moshe: three hundred sixty-five negative precepts, corresponding to the number of solar days [in the year], and two hundred forty-eight positive precepts, corresponding to the number of the members of a man’s body.” Said R. Hamnuna: “What is the text for this? ‘Moses commanded us Torah, an inheritance of the congregation of Jacob,’ ‘Torah’ being in letter-value equal to six hundred eleven; ‘I am’ and ‘Thou shalt have no [other gods],’ which we heard from the mouth of the Might [Divine].”

David came and reduced them to eleven [principles] . . . Isaiah came and reduced them to six . . . Micah came and reduced them to three . . . Again came Isaiah and reduced them to two . . . Amos came and reduced them to one . . . To this R. Nahman b. Isaac demurred . . . But it is Habakuk who came and based them all on one [principle], as it is said, “But the righteous shall live by his faith.”

The Aseret ha-Dibrot are conspicuously absent among the principles to which the 613 commandments can be reduced. In fact, elsewhere the Sages stress the opposite, namely that the Aseret ha-Dibrot are encapsulated in other Torah passages. Yerushalmi Berakhot states that the Aseret ha-Dibrot are referenced in the Shema; Midrash Tanhuma says they are embedded in the commandments at the beginning of Parshat Kedoshim. As noted above, it seems reasonable to conjecture that the Sages did not want to present the Aseret ha-Dibrot as principles embodying the whole Torah for fear that their prominence might diminish the luster of the other commandments.[2]

Yet the Aseret ha-Dibrot are not entirely absent from the passage in Makkot. R. Hamnuna states that the gematria, or numerical value, of the word “Torah” is 611. In order to reach R. Simlai’s count of 613, one must also include “Anokhi” and “Lo yiheyeh lekha,” which were heard from God directly (mi-pi ha-gevurah). Anokhi and Lo yiheyeh lekha are, of course, the first two of the Aseret ha-Dibrot. The Talmud thus emphasizes that although these two commandments are part and parcel of the 613 mitzvot, they are still different, not because they are more important, but because they were spoken directly by God to the people.[3] Paralleling the shift from devarim to dibrot, the talmudic discussion shifts the focus from content to speech. Anokhi and Lo yiheyeh lekha are two commandments among many, but they are unique because the nation heard them directly from the mouth of God.

Further, the term dibrot, or the singular form often used by the Sages, dibur, often captures not just the revelatory aspect of divine speech but also its ineffability. The Bavli in Rosh Hashanah (27a) states, “[The commandments] Zakhor and Shamor were said in one utterance (be-dibur ehad), what the mouth cannot speak and the ear cannot hear.” The Mekhilta (Yitro 20:1) similarly writes that God spoke all Ten Commandments “in one utterance (be-dibur ehad), which is impossible for a flesh and blood creature to do.” In these passages, the Sages declare that all ten commandments were spoken simultaneously, a manner of speech of which only God is capable. By invoking the word dibur in terms of ineffability, while the highly similar word diber in Yirmiyahu connotes an encounter with God, the Sages seem to suggest that divine speech possesses two almost contradictory aspects. Even as it is uniquely revelatory and transparent, it is also uniquely inhuman and inscrutable. God’s speech conceals as much as it reveals. (See also Rambam, Guide to the Perplexed, II:33).

Indeed, the Torah’s account of Sinai drives home this point. It recounts an awe-inspiring theophany, yet some basic details of the experience are shrouded in mystery. Did the people hear any commandments directly from God? The story in Shemot is not at all clear. We read, “Moshe spoke, and God answered with a voice” (Shemot 19:19). What does that mean? “The people witnessed the thunder and lightning, the blare of the shofar, and the mountain smoking,” but in their terror, they retreated and asked Moses to intercede (ibid., 20:15-18). It almost sounds like they backed out before they heard God speak. The Torah’s account in Devarim is clearer, and largely suggests that the nation heard all Ten Commandments directly from God (Devarim 5:19-28). And yet, Devarim 5:5 again suggests that Moshe served as some sort of intermediary during the event.

Perhaps the rabbinic passages explored above speak to this confusion. On the one hand, the Sages preserve direct revelation by stressing that Israel heard at least two commandments, but on the other, they acknowledge the text’s ambiguity by suggesting that perhaps the people heard no more than two; and that, in any event, what they heard was be-dibur ehad—an utterance radically different than human speech. Revelation, divine in its nature, is not entirely comprehensible in human terms.

Perhaps, then, when we stand for the Ten Commandments, we are meant to be reminded of Sinai’s paradox: sometimes it is when God is closest that He is also most difficult to understand.

[1] Some have suggested that Christians taught that God requires one to observe only a portion of the Ten Commandments and a few other matters (Luke 18:20, Mark 10:19). There is also a fascinating midrash that attributes to Korah the view that only the Ten Commandments are divine. Also of note, the first-century Jewish writer Philo placed great emphasis on the Ten Commandments, considering them general categories under which all the other commandments could be placed. For further study, see Ephraim E. Urbach, “The Decalogue in Jewish Worship” and Yehoshua Amir, “The Decalogue According to Philo,” in The Ten Commandments in History and Tradition, Ben-Zion Segal and Gershon Levi, eds. (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1990).

[2] Rabbinic literature is, unsurprisingly, not entirely uniform on this point. The Yerushalmi (Shekalim 25b) states, “Just as at sea there are huge waves, with a host of little waves between them, so are there Ten Commandments, with a host of refinements and particular commandments of the Torah between them.” This statement reserves a special place for the Aseret ha-Dibrot. The Mekhilta (Yitro 20:2) raises the possibility that the Aseret ha-Dibrot should have been placed at the very beginning of the Torah. Some later writers also assigned special prominence to the Ten Commandments. Rav Sa’adiah Gaon, for example, wrote liturgical works for Shavuot that subsume each of the 613 commandments under one of the Ten Commandments. And some, based on the ruling of Rav Yosef Karo, continue to recite the Aseret ha-Dibrot every day, albeit privately, not publicly. Maharshal even advocated for their public recitation before Barukh she-Amar. In different places and times, communities and individuals have struck different balances in determining the proper role and place of the Ten Commandments. See Urbach, ibid., pp. 182-84; and Rabbi David Golinkin, “Whatever Happened to the Ten Commandments?” Still, I have followed what I believe to be the primary thrust of rabbinic literature.

[3] In Shir Hashirim Rabbah, the Rabbis debate whether the people only heard the first two commandments directly from God, or whether all ten were part of the national revelation.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.