Ezra Zuckerman Sivan

This essay is dedicated to the memory of the author’s father, Avraham Zalman ben Yehudah Yaakov, Alan S. Zuckerman, whose tenth yahrzeit will be observed on the 30th of Av.

In her recent book Women & Power, Mary Beard argues that classical Greek and Roman culture exhibited an “abomination of women’s public speaking,” thus silencing women from “speech-making, debate, and comment: politics in its widest sense.”[1]

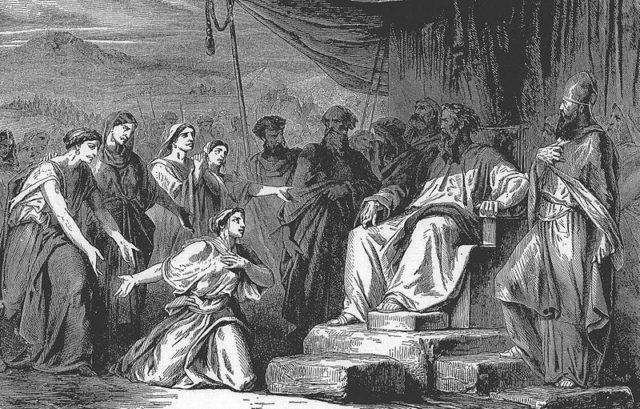

With this context in mind, it is remarkable that the only time the Torah (and Hebrew Bible more generally) describes a group of identified (i.e., with names) petitioners publicly arguing for legal accommodation, the petitioners are five women and their bid is successful:

A petition was presented by the daughters of Zelophehad, son of Hefer, son of Gilead, son of Makhir, son of Manasseh, of the family of Joseph’s son Manasseh. The names of these daughters were Mahlah, No’ah, Hoglah, Milkah and Tirtzah. They now stood before Moses, Eleazar the priest, the princes, and the entire community at the Communion Tent entrance with the following petition: “Our father died in the desert. He was not among the members of Korach’s party who protested against God, but he died because of his own sin without leaving any sons. Why should our father’s name be disadvantaged in his family merely because he did not have a son? Give us a portion of land along with our father’s brothers.” Moses brought their case before God. God spoke to Moses, saying: “The daughters of Zelophehad have a just claim. Give them a hereditary portion of land alongside their father’s brothers. Let their father’s hereditary property thus pass over to them…” (Numbers 27:1-11)[2]

This story certainly does not indicate any problem with women’s public speech. To the contrary, the tone and the content of the response are both quite favorable. The implication is that human beings may partner with God to perfect the law, and that women may play a leading role in this partnership. Moreover, the rabbinic sages (rough contemporaries of the classical Greeks and Romans) certainly interpreted the story in such a manner. We are told that Zelophehad’s daughters “were wise; were [excellent] exegetes; and were righteous (Bava Batra 119b).” The Talmud goes on to elaborate on various aspects of their petition that justify this praise, and later commentators are effusive as well.

But if rabbinic approval of these women seems well-grounded in the text, it is more difficult to understand rabbinic praise for their father Zelophehad. In particular, let us focus on an influential midrash cited by Tosafot (Bava Batra 119b), which I will call the good-gatherer theory.[3]

The first part of the theory, which is attributed by the Talmud to R. Akiva (Shabbat 96b), is that Zelophehad was the anonymous man who was stoned to death for gathering wood on Shabbat (Numbers 15:32-36); the second part of the theory is that the wood-gatherer actually had good intentions: in the wake of the Sin of the Scouts and the punishment of forty years of wandering until the generation was succeeded by their children, he sought to demonstrate that the Torah’s commandments applied even to people who had essentially been consigned to death row. In short, the good-gatherer theory holds that by violating the law and eliciting strict enforcement (via his own execution), the wood-gatherer (Zelophehad) sacrificed himself on behalf of the collective.

This good-gatherer theory is attractive in at least two respects: It helps resolve the puzzle of why Zelophehad’s daughters cite their father’s “own sin” as a point in favor of their petition; and it suggests why the Torah refrains from blackening the wood-gatherer’s name (while not hesitating to do so in the parallel case of the blasphemer; Leviticus 24: 10-23).[4]

And yet, textual support for the good-gatherer theory seems rather thin. More generally, the theory exemplifies the kind of midrashic exegesis that can frustrate the modern reader who has little patience for apologetics that distort the plain meaning of the biblical text. What’s more, if this is indeed apologetics, it is unclear what it accomplishes. What do the Sages achieve by linking these seemingly unrelated stories? What is the connection between a man who violates the Shabbat (to elicit strict enforcement) and women arguing that their family not be disinherited?

I address these questions in two steps. First, I discuss how the good-gatherer theory has much stronger grounding in the text than appears at first blush. Next, I show that the thematic connection between these two stories runs surprisingly deep. In short, it would appear that this midrash anticipates an interpretation of the wood-gatherer story I proposed in Lehrhaus two years ago: that it is a vehicle for teaching us about the threat of unrestrained social competition. And if the wood-gatherer invites us to consider what would happen to the Shabbat and to social cooperation generally were we to allow anyone to ‘raid’ valuable public resources while everyone is resting, the daughters of Zelophehad invite us to consider the downside of allowing living male relatives to carve up the legacy of their dead kinsman. More generally, the good-gatherer theory directs us to scriptural hints at the danger lurking behind collective projects such as building the Shabbat/seven-day week and conquering and settling the land of Israel.

Evidence for the Good-Gatherer Theory

The only textual evidence adduced by the Talmud to support the good-gatherer theory is that just as Zelophehad’s daughters enigmatically describe their father as having “died in the wilderness,” the story of the wood-gatherer is enigmatically introduced as having occurred when “the Children of Israel were in the wilderness.” But especially given the fact that other incidents, including the sin of the scouts and its aftermath also occur “in the wilderness” (Numbers 14:16,22,29, 32-3, 35), this seems like quite a thin reed upon which to hang a theory.

In fact, however, there is quite a bit more textual support for the theory than meets the eye.

First, it is not clear what other incident might have led to Zelophehad’s death. The words “his own sin” suggests that Zelophehad was killed for an individually-initiated action rather than an action that incites a communal sin (see Rashi, ad loc.; Sifrei Numbers 133:3).[5] And all other individual transgressions besides the wood-gatherer are committed by named protagonists.

Second, as noted by Rabbanit Sharon Rimon,[6] four literary parallels between the story of the wood-gatherer and that of Zelophehad’s daughters suggest a close link between them: (a) each of the incidents revolves around a case being brought (k-r-v) to trial before Moses, the high priest, and the entire congregation;[7] (b) in each incident, God must be consulted because human judges do not know how to decide the case; (c) in each incident, there is a Masoretic paragraph break between the presentation of the case and the adjudication of it; and (d) whereas the wood-gatherer stands out for the absence of the subject’s name, Zelophehad’s daughters are motivated by the prospect of their father’s name being absent from the record.

There is yet another compelling textual basis for taking the good-gatherer theory seriously. In particular, the very first mention of Zelophehad and his daughters seems to signal both that he did something wrong and that there were mitigating circumstances. To see this and to appreciate the larger thesis developed below, it will be valuable to review chapter 26 of Numbers.

Overall, this chapter describes the census of the fortieth year. The households/families that constitute each of the twelve tribes are discussed, as well as the total number of males in each tribe; and then after an interlude that mentions the lottery system by which the land of Israel would be allocated, there are reports on the census of the Levites and notes on how they would not be partaking in the land allocation.[8]

Now observe how five narrative snippets are embedded in the censuses.[9] Of these five pieces of narrative, four of them refer to well-known incidents in which one or more people transgressed and therefore lost their lives: (a) The party of Korah (but not his sons; Numbers 26:9-11, referring to Numbers 16); (b) Judah’s eldest sons Er and Onan (Numbers 26:19, referring to Genesis 38:7-10; cf., Genesis 46:12); (c) Aaron’s eldest sons Nadab and Abihu (Numbers 26:61, referring to Leviticus 9:23-10:3; cf., Numbers 3:4); and (d) the generation of the Exodus who, with the exception of Joshua and Caleb, do not appear in the new census because of the sin of the scouts (Numbers 26: 64-65, referring to Numbers 13-14). The pattern from these four cases seems clear. The last narrative snippet reminds the reader why certain people are no longer alive to be included in this new census and the earlier narrative snippets remind the reader why certain families are missing and will thus not be able to take up their place as households in their tribal territory.

Zelophehad and his daughters are the focus of the fifth narrative snippet. Oddly, after telling us that each of the five sons of Manasseh’s grandson Gilead had been accorded household status, a cryptic verse (26:33) adds seemingly extraneous information about the sons of this fifth son, Hefer: “And Zelophehad son of Hefer had no sons but just daughters; and the name (sic) of the daughters of Zelophehad: Mahlah and No’ah, Hoglah, Milkah and Tirtzah.” This verse may not raise the eyebrows of the casual reader because it seems intended to provide context for the story of the daughters’ petition in the next chapter. But such context is redundant with that provided in the story of the petition itself (as exhibited above). What’s more, in no other tribe except Manasseh does the Torah trace a genealogy down to the fourth generation. The text seems to be going out of its way to include this information. Given the theme of the other narrative snippets, the implication would seem to be that Zelophehad did something wrong that undermined his claim in the land allocation. But in sharp contrast to the other four narrative snippets, the verse refrains from informing us that Zelophehad did something wrong, nor does it even tell us that Zelophehad died. Finally, only in the case of Zelophehad are the “transgressor’s” descendants named, with the strong implication that they—like everyone else who is listed in the census—have a claim to the land.

Overall then, there is good reason to take the good-gatherer theory seriously. The text of Numbers 26-27 is inviting us to develop some theory that could account for why Zelophehad did something problematic and why his legacy would be in his daughters’ hands. As for why we might entertain the good-gatherer theory specifically, not only is the wood-gathering incident the only personal transgression that is otherwise unaccounted for, and not only are there notable intertextual linkages between the two stories, but the text seems to hint that Zelophehad did something that could cause him to lose his share in the land allocation, but that there were mitigating circumstances.

The Deeper Connection

Still, even if we concede the possibility that Zelophehad may be the good-gatherer, it’s not clear why the connection should be meaningful. The Torah after all, is not a history book; if it were, we might fault it for not spelling out who the wood-gatherer was and what Zelophehad did and did not do wrong. Rather, the Torah is prophetic literature[10] whose very gaps are designed to make us probe for deeper lessons below the text’s surface.[11] But what is the lesson conveyed by the idea that Zelophehad was a good-gatherer?

In a Lehrhaus essay two years ago, I discussed how the wood-gatherer story is a vehicle for teaching us about the grave threat to social order, and specifically to the fledgling institution meant to promote and safeguard that social order (the Shabbat/week), posed by the individual who pursues his/her private interests without regard to the collective. This theme is brought out clearly via the way the wood-gatherer story plays off three other stories: that of the first week/Shabbat, involving the manna (Exodus 16); Pharaoh’s “anti-Shabbat temper tantrum” (Exodus 5); and the “wood-gathering woman” (I Kings 17). Whereas Pharaoh pits every individual against the other, the miracles of the manna (everyone ended up with as much as they needed regardless of how much they collected; storage was impossible) served to neutralize the incentive for individuals to pursue private interests at the expense of the collective. But if such incentives were neutralized when it came to food (manna), they were not when it came to fuel (wood): the wood-gatherer acts on these incentives at the expense of the collective. Thus the wood-gatherer story dramatizes the threat to social order from situations where individuals behave as if it is each man for himself.

The key to unlocking the mystery of the wood-gatherer is to consider the counterfactual conditions under which anyone might get very angry to discover that someone had gathered wood. At first blush, this seems difficult; but on deeper reflection, it is not: just imagine a situation where the wood is extremely precious—at the extreme (the case depicted by the wood-gathering woman) a small amount of wood may be necessary for keeping your child alive. It seems that this was the case in the wilderness (as is hinted in Numbers 13:20). As such, one can imagine the anger the wood-gatherer would have elicited. One is almost astonished that they brought him to Moses. As I noted at the conclusion to the essay, the more natural responses would either have been to follow the wood-gatherer’s lead and “raid the commons” or to lynch him as they had recently threatened to do to Caleb and Joshua (14:10).

Let us now use this counterfactual logic to appreciate how a similar challenge lurks behind the story of the daughters of Zelophehad and more generally, behind the conquest and allocation of land described over the last 11 chapters of the book of Numbers. In short, we should be astounded by the fact that the allocation of land was as peaceful as it was and wonder how this was achieved. The counterfactual is that the various families and tribes could have turned on one another over who would have to risk their lives for the land and who would get the largest and choicest pieces of it. And just as the judicial process elicited by the wood-gatherer helped to thwart a social breakdown threatened by egoistic behavior in the wilderness, Zelophehad’s daughters seem to help prevent a more general version of this threat in (or en route to) Canaan.

One need not look very hard to find textual evidence that such a danger was salient. Chapter 32 of Numbers focuses on the request of the tribes of Reuben and Gad to stay in Transjordan and live on the lands Israel had just conquered. Moses’s angry response—“Would your brothers go to war while you remain here?!” (32:6) and the outrage with which he expressed it (“you breed of sinful men,” 32:14) captures the same kind of anger that the wood-gatherer would have evoked: these seemingly wayward tribes appeared as “free-riders” who sought to benefit from resources they had not earned. If these tribes were to “think only of (themselves),” wouldn’t the other tribes be “fools” if they didn’t behave likewise?[12] How could they then sustain the fragile social cooperation needed to sustain a pan-tribal army to conquer and allocate land?

Reuben and Gad addressed Moses’s concern by pledging to be the vanguard of the military conquest of the land—land that would be given to their fellow tribes rather than to them. They would even put their families and livestock at some risk in Transjordan. This was apparently insufficient however. Perhaps to further limit the sense that these tribes had overreached, Moses compelled them to share the Transjordan with half of the tribe of Manasseh even though they had not requested it (compare 32:33-42 with 32:1-32).

There is an important textual theme that both hints at the generality of this threat to collective cooperation posed by the conquest and division of the land and which links it to the wood-gatherer story. In particular, there are five occasions in the entire Hebrew Bible where the text contrasts versions of the words “great” and “little” (rav/marbeh/yarbeh vs. me’at/mam’it/yam’it) to discuss the allocation of property: (a) the collection of the manna (Exodus 16:17-18); (b) the donation of the half shekel in the first census (Exodus 30:15); (c) the calculation of land value in the context of the jubilee (Leviticus 25:16); (d) the charge to the scouts to assess the Canaanite population (Numbers 13:18); and (e) (four times) the lottery by which the land west of the Jordan would be allocated (Numbers 26:54; 26:56; 33:54; 35:8).

The underlying theme seems quite clear. The threat from intense social competition is explicit in the first case, which as noted above, serves as a counterpoint to the wood-gatherer; the miracles of the manna are necessary to maintain social order. The parallel threats from egoism in the other cases vary in how explicit (the jubilee) and subtle (the half-shekel) they are.[13] Finally, note how pivotal stories of conflict (“the cravers” <see Numbers 11:32>; Korah’s rebellion <see 16:3,7,9>; and Reuben and Gad’s request <Numbers 32:1>) are marked by the use of “great” without “little” or vice versa, in each case pointing to how social order breaks down when egoistic tendencies are not held in check.

What about the land allocation? When viewed through the lens of Moses’s response to Reuben and Gad, it should be no surprise that the discussions of the land allocation are shot through with suggestions of the importance of moderating the tendency for people to compete over the “great” so they don’t end up with the “little.”

The Torah presents two basic principles for allocating land: (a) that land will be allocated on the basis of relative population size, with larger tribes and households (within tribes) getting more and smaller tribes (within households) getting less; and (b) that a lottery would determine which plot belongs to which household. But this hardly settles all questions the interested parties would have had. For one thing, the relative size of groups is a moving target; thus, the Talmud (Bava Batra 118b) records a dispute (based on ambiguities in the text of Numbers 26) as to whether the land is allocated based on the generation that arrived in the land or based on the generation that left Egypt. Moreover, even if we were to clear up this matter, there is the question of how to delineate borders in a land that has yet to be conquered (so some of the allocated land cannot be settled) or surveyed (so borders and boundaries are yet to be delineated). The larger risk in such a situation should be clear. It is the same threat that the wood-gatherer threatened to unleash.

The Daughters’ Legacy

The good-gatherer theory, and the significant textual support that underpins it, sensitizes us to the lurking risk that social cooperation would break down due to pernicious social competition over land and the sacrifices to acquire it. It also suggests that the daughters of Zelophehad played a role in mitigating this risk. But how?

An answer to this question is suggested by the Talmud’s explanation (attributed to R. Shmuel bar Rav Yitzchak) for why the daughters should be considered wise:

Moses our teacher was sitting and interpreting in the Torah portion about men whose married brothers had died childless, as it is stated: “If brothers dwell together…” (Deuteronomy 25:5). The daughters of Zelophehad said to Moses: If we are each considered like a son, give us each an inheritance like a son; and if not, our mother should enter into levirate marriage. Immediately upon hearing their claim, the verse records: “And Moses brought their cause before the Lord” (Numbers 27:5).[14]

This midrash is founded on the recognition that the daughters’ petition must be understood in the context of the institution of levirate marriage (yibum), the ancient rite (found also in other ancient/patriarchal cultures) by which a brother of a man who dies without children marries the childless widow and dedicates their child to his dead brother’s legacy. In particular, Moses’s discussion of this rite in Numbers 27:5 is clearly in dialogue with the daughters’ petition, as reflected in the use of multiple, distinctive keywords: “has no son” and “brothers.” But the daughters rightly point out that if levirate marriage addresses the situation when a man dies with no sons, it is not clear what should happen if the man does have daughters.

And yet if it takes great wisdom to recognize this lacuna, it is curious that so little seems to be accomplished by filling it. Numbers concludes (36:1-12) with a successful petition by the women’s cousins, which requires (or merely recommends; see Bava Batra 120a) the women to marry within their tribe. This ensures that a tribe’s total allocation will not be reduced as a result of granting a dead man’s land to his daughters. The daughters are told that they should marry “whoever is good in their eyes” (36:6) from among their cousins, and so they subsequently do (36:10-11). But then what is accomplished by having a dead man’s land go to the man’s nephews rather than his uncles? Is this really so significant that these marriages should be the climax of the book?

It may help to ponder two counterfactuals, one pertaining to the daughters’ petition and one pertaining to their cousins’ petition. Imagine first that the daughters’ petition were denied and the land were allocated to the uncles instead: this would set the uncles in competition with one another. Some uncles (perhaps the oldest) would end up with more land than the others. This would break the larger principles of allocation by family and presumably set the stage for dangerous fraternal competition.[15] One begins to worry about scenarios in which the brothers of the dead man would take initiative to try and wrest the land from each other, perhaps by surreptitiously killing a brother (and his sons?) and inheriting his land. Such fratricide could even be contemplated prior to a natural death, perhaps given the fear that one’s brother might strike first. The context of war (as was in the offing at the time of the daughters’ petition) could potentially serve as a useful cover (cf., I Samuel 18:17; II Samuel 11:15): it would seemingly be the enemy who killed him, not his brother.

But this nightmare scenario would be unlikely if uncles have to kill their nieces (who were not soldiers) as well. Thus, the initial adjustment in the law in response to the daughters’ petition helps to limit fraternal competition in two ways. First, proportionality in the original allocation is preserved—Zelophehad (and perhaps others who died before the allocation) receive an allocation just as their brothers do. And giving the daughters title helps to provide a buffer against competition among the uncles.[16]

Now consider a second counterfactual, as pertains to the cousins. In particular, what might have happened had Moses granted the cousins’ petition and required the daughters to marry their cousins, but had not also stipulated that “to the man who is good in their eyes they will marry?” Not only does this remarkable clause challenge patriarchal preconceptions by promoting the idea that women have the right to choose their own spouses, it also sets the terms for competition among the cousins for the land. To be sure, the women will not hold title to the land after the first generation (an adjustment that helps to mitigate potential competition between tribes). But if their tribal cousins want to gain that title, they cannot obtain it by fighting with each other. Rather, they must instead impress the women that they will be good husbands. Again, a threat to destructive social competition is neutralized.

Finally, the codification of the daughters’ petition helps to bolster the importance of first-generation family legacies, which thereby dulls the incentives of later generations to compete fiercely over land. The jubilee laws’ requirement that land will always be controlled by a first-generation family (Leviticus 25:8-15) provides the basic foundation here as it ensures that a given territory will always be identified with a first-generation patriarch. The daughters’ petition reinforces this. But in reinforcing the identity of the land with a deceased ancestor, it also indicates how this system helps to loosen the link between the patriarch and the patriarchy. In particular, what is being illustrated is that the first-generation family name is akin to a corporate brand, one that daughters can potentially administer as much as sons.

Conclusion

The foregoing discussion reminds us that when midrashic ideas seem divorced from the biblical text, this constitutes an invitation to read the text more closely to listen for larger themes to which the Sages were attuned. To be sure, while the foregoing provides much better grounding for the theory than it would seem to have at first blush, one could argue that the textual evidence for the first part of the theory (that the wood-gatherer is Zelophehad) is stronger than it is for the second part of the theory (that his intentions were good). As noted above, hints that the wood-gatherer was well-intentioned are (a) that the daughters think that the fact that Zelophehad died for his own sin is a point in his favor, and (b) that the narrative snippet in Numbers 26:33 is akin to the other narrative snippets that mention disinheritance due to capital crimes, but no such crime or death is mentioned here. One could also argue that if the wood-gatherer was Zelophehad but he was an ill-intentioned commons raider, it would be less clear how the daughters were fulfilling his legacy. But if he was indeed well-intentioned, then the daughters are following in their father’s footsteps by making a great personal sacrifice to perfect (enforcement of) a law meant to protect communal cooperation.

Yet focusing on whether Zelophehad really was the wood-gatherer and whether his intentions really were good misses the fact that the value of the theory is less in establishing what actually happened “in the wilderness” than in how it leads us to recognize the Torah’s deeper message. Indeed, while Talmud itself records R. Yehudah ben Beteira’s dissenting opinion (see Shabbat 97a) that the wood-gatherer was one of the “defiers” (or ma’apilim), an appreciation for the deeper theme unlocked by the good-gatherer theory suggests how the two positions may actually have a common foundation. In particular, the defiers (who failed in their attempt to invade Canaan when Moses warned them not to; Numbers 14:40-45) also represented a threat to collective cooperation, one that related to the land but was the opposite to that posed by Reuben and Gad. In particular, the issue was not one of letting others shoulder the responsibility of conquest but of taking up that responsibility on their own. What if they had succeeded? Even if their intentions were originally pure, they would now face the temptation to claim the largest and choicest pieces of land for themselves (recall that this is before the principles of land allocation were declared). In this sense, they were also commons-raiders just as the wood-gatherer was![17]

More generally, the good-gatherer theory has led us to appreciate the Torah’s deep sensitivity to the dangers of pernicious social competition and how it threatens both the infant institution of the Shabbat/seven-day week and an infant nation that must remain cohesive and strong enough to conquer and settle the land. (It is perhaps all too fitting that these dangers are connected by a name, Zelophehad, that appears to mean “shadow” of “fear”). As noted, the latter theme is explicit in the heated negotiations between Reuben/Gad and Moses, and it is hinted at by how the textual refrain of balancing “great” and “little” runs through the description of the land allocation process (based on lottery and family size) just as it does in earlier cases where egoism threatens social order. Additional tantalizing textual hints bolster this interpretation.[18] Upon reflection, it seems clear why it would be difficult to arrive at a fair distribution of the burden of conquest and of the rights to land, and why the land allocation process may not have been sufficient to address all the important issues. Enter the daughters of Zelophehad to recognize the looming threat and to help reinforce the principles of proportionate allocation.

But if we have seen how it makes sense to see Zelophehad’s daughters as furthering the legacy of the wood-gatherer, one wonders why it is fitting for this to occur via a public campaign by five women during an era when public female speech was unusual, to say the least. It may be instructive that this story is just one of several biblical stories in which women are depicted as boldly and successfully challenging men in a bid to advance their families’ interests. Remarkably, in each of these cases, the women act not to promote their personal names and legacies but that of their fathers (in the case of Zelophehad’s daughters); their dead husbands (in the case of Tamar, Ruth, and arguably Bathsheba)[19]; or their sons (in the case of Sarah, Rebecca, and Rachel and Leah). But in each case, their self-sacrifice is rewarded with preservation of their own names and legacies such that they are today at least as famous as the men in question.[20] To that end, it is notable that while the daughters of Zelophehad are singled out by name once again in Joshua (17:3), their cousins/husbands are never named.[21] What better way to counter the threat of egoism than to confer status on those who seek it for others rather than for themselves?[22]

Note finally how just as in the first case of collective speech by biblical women (Rachel and Leah in Genesis 31:14-16), the story of the daughters of Zelophehad (a) overcome sisterly rivalry to act as one; and (b) leverage this collective action to transform themselves from objects to be acted upon by men into authors of their own fates.[23] These twin achievements may be a far cry from eliminating patriarchy; but they are impressive precisely because they occur within the patriarchal system and raise questions about its underlying principles. Moreover, an appreciation for these achievements reinforces why the story of the daughters of Zelophehad are such an exquisite narrative vehicle for rebuking the human (male) tendency to engage in ruinous social competition. What better way to convey this message than for the objects of such competition to speak loudly and convincingly against it?

[1] Mary Beard, Women & Power: A Manifesto (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2017), 13.

[2] Translation by Aryeh Kaplan, The Living Torah.

[3] The text of the original midrash cited by Tosafot is not extant. Writing more than a thousand years earlier during the tannaitic period, Targum Jonathan (Numbers 15:32) seems to cite the same tradition when he writes that the wood-gatherer was from the “sons of Joseph” and that his intentions were pure (to clarify the punishment for Shabbat violation).

[4] In that respect, it addresses R. Yehudah ben Beteira’s objection to R. Akiva, which is that if R. Akiva is right, the Torah must have had reasons for concealing Zelophehad’s identity. Note however that this theory is in tension with the opinion of R. Hideka, citing R. Shimon Ha-Shikmoni (Bava Batra 119b) whereby the wood-gatherer is described as contrasting with the daughters of Zelophehad: the latter are “meritorious” but he is “liable.”

[5] This may be why R. Yehudah Ben Beteira’s theory (Shabbat 97a)—that Zelophehad was one of the “defiers” (the ma’apilim) who sought to enter the land after the Sin of Scouts without divine protection—has not attracted as many adherents as R. Akiva’s theory.

[6] Rabbanit Sharon Rimon, “The Daughters of Tzelofchad,” trans. Kaeren Fish. Available at http://www.hatanakh.com/sites/herzog/files/herzog/parsha68-41-68pinchas-srimon.pdf.

[7] In the case of the daughters of Zelophehad, the tribal princes are also in the audience for the petition– which is fitting given the subject matter at hand.

[8] We learn in chapter 35 that they receive special cities—which would also be cities of refuge—in which to dwell. And we learn earlier, in chapter 18, that the Levites would be sustained by a tithe.

[9] A possible sixth snippet is the verse stating “the name of Asher’s daughter is Serah” (Numbers 26:46; cf., Genesis 46: 17). See note 23 below for discussion.

[10] See e.g., Menachem Leibtag, “Introduction to Sefer Bereshit.”

[11] Menahem Perry and Meir Sternberg, “The King through Ironic Eyes: Biblical Reading and the Literary Reading Process,” Poetics Today 7:2 (1986): 275-322.

[12] Joseph Heller, Catch-22 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961), 446.

[13] Many commentators have noted how the half-shekel limits social competition (see e.g., Mosheh Lichstenstein, “An Egalitarian Obligatory Contribution,” The Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash). It is perhaps hardest to see the relevance of this theme to the scout’s charge. Perhaps the implicit idea is that a larger Canaanite population would exacerbate internal Israelite competition, either because the conquest would be more challenging or because there would be less land to allocate.

[14] Bava Batra 119b, Davidson translation.

[15] There remains the potential for fraternal competition among brothers. This presumably is mitigated by existing norms of primogeniture that the Torah endorses (Deuteronomy 21:17).

[16] It never completely eliminates it, however, as in the case where there are neither sons nor daughters and the widow can no longer bear children to a would-be levir. At the end of the day, laws against murder and theft provide the ultimate barrier.

[17] Thanks to Dr. Jeremy England for suggesting the connection between the defiers and the wood-gatherer as commons-raider.

[18] In brief, there is a remarkable pattern whereby all the stories involving contested land claims pertain to the tribe of Manasseh and specifically his son Makhir and his grandson Gilead. Moreover, not only is Gilead Zelophehad’s grandfather, but it is the place name for the area that is at the epicenter of many generations of land, property, and family disputes going back to Genesis 31 and continuing into future generations as late as Judges 11. As for why these issues center on Manasseh, this may be because Manasseh appears to have the weakest claim to tribal status. The other tribes have reason to resent Jacob’s decision to give Joseph a double portion to Joseph by conferring tribal status on each of his sons (rather than on Reuben, as dictated by Deuteronomy 21:17; cf. Genesis 49:3!), and Ephraim can claim that Jacob gave him primacy over Manasseh (48:20). That this story is a harbinger for contestation on (and resolution of) these issues in Numbers may be hinted at by the enigmatic note that Makhir was alive at the time of Joseph’s death (thus bolstering Manasseh’s claim?) at the conclusion of Genesis (50:23).

[19] See the discussion under “Countering the Danger of Confession” in my Lehrhaus essay from last fall, “The King’s Great Cover-Up and Great Confession.”

[20] One wonders why therefore the wood-gathering woman of I Kings 17 is not named. Perhaps it is because she is struggling less for the legacy of her son than for his life.

[21] Not only that but quite strikingly, the “Samaria Ostraca” records the place names Hoglah and Noah as being within the Hefer district. It would appear then that the daughters’ names were preserved. See e.g., Ivan T. Kaufman, “The Samaria Ostraca: An Early Witness to Hebrew Writing,” The Biblical Archaeologist 45:4 (1982): 229-239.

[22] Given this, one wonders if the text is hinting that Serah (see note 10) is remembered for similar selflessness.

[23] On these themes, see my Lehrhaus essay from last fall, “Team of Rivals: Building Israel Like Rachel and Leah.” It is intriguing to consider a link between these episodes via the book of Ruth. As discussed in that essay, Ruth twice uses an ungrammatical combination of the masculine and feminine forms to describe pairs of women– Ruth and Naomi (Ruth 1:19) and Rachel and Leah (4:11). Similarly, in saying that the daughters of Zelophehad should marry whoever is “good in their eyes,” Moses twice uses masculine words (eineihem; akheihem) when he should use the feminine (Numbers 36:6). As suggested by R. Moshe Alsheikh’s comment on Ruth (1:19), this seems to reflect a recognition of female agency.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.