Tovah Lichtenstein

“The facts are not at all like fish on the fishmonger’s slab. They are like fish swimming about in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean; and what the historian catches will depend, partly on chance, but mainly on what part of the ocean he chooses to fish in and what tackle he chooses to use – these factors being, of course, determined by the kind of fish he wants to catch. By and large, the historian will get the kind of facts he wants” [E.H. Carr, What is History, (Penguin Books, 1964), 23].

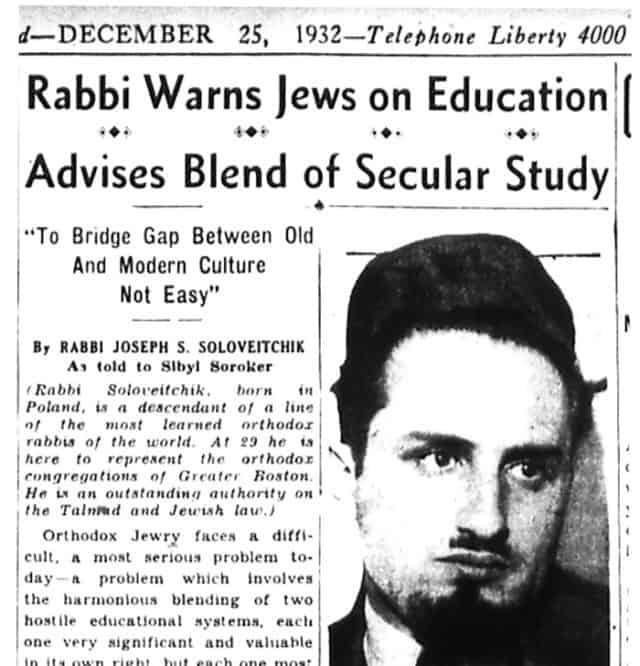

As I read the documentary report of my father’s arrival in America that was a companion piece to an interview with the Rav that appeared in the Boston Sunday Advertiser in December, 1932, entitled Rabbi Warns Jews on Education: Advises Blend of Secular Study, I, indeed, wondered what kind of fish the authors wanted to catch. Were the documents they were presenting to the interested reader related to Rabbi Soloveitchik’s Ktav Rabbanut where his duties and obligations to the community were spelled out? What indeed had he found in Boston that first winter? The authors were bothered, instead, by such crucial questions as to how my sister Atarah’s name was written in the ship’s manifest, the route that the ship took to New York and whether or not the young family was detained for a short period of time in Ellis Island. These facts are, to my mind, “fish on the fishmonger’s slab.” They have no significance for one’s understanding of the nature of the first encounter of a young European talmid hakham, with the unusual credential of a doctorate in Philosophy from Berlin University, with the Jews of Boston. These facts do not even have significance in the personal history of my family, as even with hindsight, they remain the insignificant details that are the warp and woof of daily life. Were the authors fishing in the waters of idle chit-chat?

If these irrelevancies had been the only facts reported in the article, I would have shrugged my shoulders and said “Maybe I am showing my age and still think history needs to deal with past, examine the issues and give us an understanding of what was.” But when I read the last part of the article which sets forth a lengthy exposition that tries to prove that my grandfather, Rabbi Moshe Soloveitchik penned the article in the Ha-Pardes about my father in an attempt to further my father’s chances of finding a position, as his contract with the Hebrew Theological College was terminated upon his arrival in the States, I asked myself whether the authors were fishing in the putrid waters of gossip.

Indeed, the detective work that went into proving their point is worthy of the finest sleuths. The reader is invited to put the two documents together to compare the wording. Just click the button and the true author will be revealed! Not wanting to become a participant in this game, I will not relate to the veracity of the claim. The undertone of this section of the article is “we caught you, Rav Moshe.” And, indeed, if my grandfather, with the aid of Rabbi Pardes, the editor of the journal, was trying to find a position for my father, I suggest that every father should have done the same. The year is 1932—three years into the Great Depression—and both jobs and money were scarce. If that was the point of the essay in the Ha-Pardes, I am grateful to Rabbi Pardes if it helped my father find employment.

Lehrhaus turned to me for permission to print the interview with my father, which I gladly gave, never thinking that such an article would appear. The subsequent articles that related to the interview were serious attempts to put it into the perspective of the times and the persona while this piece has paved the way for idle chit-chat and gossip.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.