Yosef Lindell

Introduction

Tucked away toward the end of the kinnot recited on Tishah Be-Av is the kinnah Yom Akhpi Hikhbadti.[1] Written by the Castilian poet and philosopher Rabbi Yehudah ha-Levi (c. 1075-1141), this kinnah recounts a devastating story found in the Talmud and Midrashic literature of how Nebuzaradan, Nebuchadnezzar’s general and one of the architects of the First Temple’s destruction, murdered thousands of Israelites to appease the bubbling blood of the priest and prophet Zechariah ben Jehoiada killed centuries earlier. Yet ha-Levi’s telling of the story is unique. Unlike the Talmudic versions, which say little about why God allowed such a tragedy to occur, ha-Levi subtly reworks the rabbinic sources to grapple with questions of theodicy. In this manner, the kinnah becomes one of a number of Tishah Be-Av texts that suggest that the day is not just for mourning, but is also a time to think about questions of theodicy and even challenge God and question divine justice.

The Rabbinic Legend of Zechariah’s Bubbling Blood

To fully appreciate ha-Levi’s kinnah, we must first survey how the story of Zechariah’s bubbling blood is told. The story appears in several places in rabbinic literature, and each time it is recounted a little differently.[2]

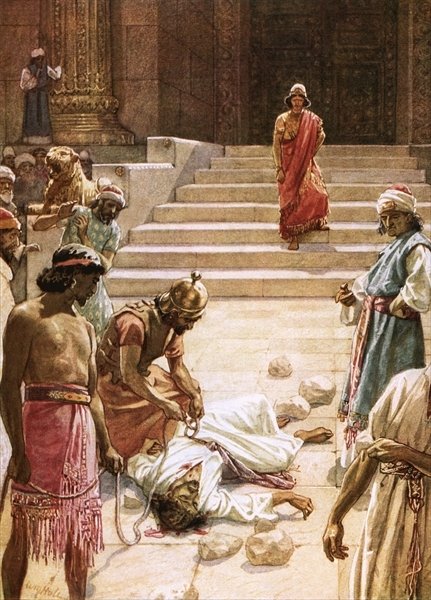

Most consider the rabbinic story to be rooted in a short incident in II Chronicles.[3] There, the Israelites in the time of King Joash have strayed from God. Zechariah ben Jehoiada prophesies in the Temple courtyard, admonishing the people for their wicked ways, but they murder him in cold blood at the king’s command. As he dies, he says, “May God see this and requite it” (II Chronicles 24:22).

All versions of the rabbinic tale share the following common elements. When Nebuzaradan and his army enter the Temple some two hundred years after Zechariah’s murder, Nebuzaradan sees blood on the ground bubbling or boiling. He asks about it, and the Israelites tell him that it is sacrificial blood. He slaughters many animals, but the blood continues to bubble. He threatens the Israelites, who reveal the truth: it is the blood of Zechariah whom they murdered long ago. Nebuzaradan decides to appease Zechariah’s blood by murdering thousands of men, women, and children. When the killing reaches a frenzy but the blood continues to boil, Nebuzaradan turns to Zechariah’s blood and asks whether he will have to kill all of the people to appease it. The blood finally rests.

Obviously there is much to unpack here, and even at its most basic level, the story raises the specter of theodicy: how could God allow Nebuzaradan to kill so many to appease the murder of one individual? The narrative is doubly unfair because Zechariah was killed centuries before the price for his murder is exacted.

There are divergent conclusions to the story in the Talmud Yerushalmi and the Talmud Bavli, and it is worth considering how each Talmudic account responds to the narrative’s unfairness. I will then contrast the two endings with ha-Levi’s kinnah. I will not directly address the midrashic versions of the story, as they tend to combine elements from the Bavli and Yerushalmi.[4]

In the Yerushalmi (Ta’anit 4:7), once Nebuzaradan murders multitudes, he addresses Zechariah:

At that moment [Nebuzaradan] rebuked [Zechariah]. He said to him, “Do you want me to destroy your entire nation on your account?”

At that moment the Holy One Blessed Be He was filled with compassion and said, “If this one, who is flesh and blood and cruel, has mercy on my children, I about whom it is written, ‘For the Lord your God is a merciful God,’ how much more so [must I show mercy]?” Immediately, [God] signaled to the blood and it was swallowed in its place.

God stills Zechariah’s blood out of mercy because Nebuzaradan belatedly shows mercy in his plea to Zechariah.

The Yerushalmi does not address the fairness of the punishment exacted by Nebuzaradan. It teaches, however, that God will have mercy on His people at the end of the day: despite what occurs, we can trust that God will not utterly abandon us.[5]

In the Bavli there is even less spiritual guidance, as God does not make an appearance. Sanhedrin (96b) tells the following:

[Nebuzaradan] approached him. “Zechariah, Zechariah, I have destroyed the best of them: do you want me to kill them all?” Immediately [the blood] rested. Thoughts of repentance came into his mind: “if they, who killed one person only, have been so [severely punished], what will be my fate?” So he fled, sent his testament to his house,[6] and became a convert.

The blood is stilled at Nebuzaradan’s request, but God is not explicitly identified as the One who stills it. Then, Nebuzaradan reasons that if the Jews were so severely punished for murdering Zechariah, how much more so will he be punished for killing them. So he flees and converts to Judaism.

This is a surprising end to the story; it raises thought-provoking questions about the nature of repentance and suggests that even the most hardened sinner can be rehabilitated. But its focus on Nebuzaradan and lack of mention of God leaves the reader somewhat theologically bereft. In the Yerushalmi at least, God proclaims His mercy at the end. But readers of the Bavli version of the story can take little consolation from Nebuzaradan’s change of heart, as in this version God remains silent. Although God is likely working behind the scenes,[7] it is still significant that this telling focuses on the lesson Nebuzaradan learns instead of offering guidance to readers who are trying to make sense of the horrors Nebuzaradan inflicted.

Despite their differences, both Talmudic accounts emphasize the human actors in the tale. Nebuzaradan is the one who pleads for mercy, and perhaps he even converts to Judaism. Nebuzaradan addresses Zechariah and his blood when asking that the flow be staunched; he does not directly address God. And as noted, neither version of the story seriously guides those struggling to process its aftermath.

Rabbi Yehudah ha-Levi’s Unique Retelling of the Rabbinic Story

Yom Akhpi Hikhbadti retells the rabbinic story of Zechariah’s blood but deviates from the Talmudic versions in several ways. Through these modifications, ha-Levi explores questions about divine justice that the Talmudic accounts do not.

The focus on theodicy starts in the kinnah’s very first lines, where it seems like the paytan thinks that God is rightfully exacting retribution for Zechariah’s murder. The kinnah begins, “The day of my oppression weighed heavily upon me, and my sins doubled, as I sent my hand against the life of a prophet in the very courtyard of God’s Temple.”[8] Here, the narrator ahistorically takes personal responsibility for the murder of Zechariah although it happened over two centuries prior. After this declaration of collective guilt, the narrator braces for the consequences. Once Nebuzaradan arrives, the narrator remarks as an aside, “And I said to myself, ‘This is your sin, and this is its fruit!’”[9] In this line, the narrator embraces intergenerational punishment, suggesting that the impending massacre is justified by Zechariah’s murder.[10]

Yet the narrator’s initial justification of God’s judgment does not hold up. Matters quickly degenerate. Since the kinnah is told in the first person, as if by one who was actually present, the killings hit harder than in the rabbinic versions. The poet also uses language that is more immediate and personal. When he writes, “And the school children [were slaughtered] before the eyes of their fathers,” one realizes, with sickening dread, that it was not faceless myriads who were murdered, but parents saw their children die. And it keeps getting worse: when the paytan tells that “[Nebuzaradan] continued to kill women with nursing babes,” one wonders how the murder of blameless infants could possibly ever be just. The disproportionality of the punishment for Zechariah’s murder screams out from between the lines.

And that brings us to the story’s conclusion, where we see the starkest difference between the kinnah and its rabbinic sources:

[Nebuzaradan] continued to kill women with nursing infants,

blood rising among them like the sea and the River Nile,

until Nebuzaradan lifted his eyes heavenward

and said, “Is this not enough, the blood of Jerusalem’s daughters?

Will You eradicate completely the remnants of the captivity?”

Then the innocent blood quieted, and the

sword of vengeance had its fill.

The killings have become too much for even the murderer to bear. So in the closing verses, Nebuzaradan himself calls out to heaven—God, make it stop! In all of the rabbinic versions of the story, Nebuzaradan addresses Zechariah. In the kinnah, however, he addresses God in heaven. What’s more, the words “will You eradicate completely the remnants of the captivity?” appear to directly blame God for the massacre.

Nebuzaradan’s final outburst stands in stark contrast to the narrator’s own muteness. Perhaps, for the anonymous bystander narrator, God in His infinite wisdom has ordained the punishment to fit the crime. But from another perspective, the narrator’s religious quietism is patently absurd. When all is said and done, every sin has its measure. So when the blood rises like the raging Nile, Nebuzaradan confronts God and accuses Him, “Will You eradicate completely the remnants of the captivity?” The question hangs in the air, but we know that God accepts the rebuke, because the blood rests. And although it is somewhat ironic that it is Nebuzaradan, and Nebuzaradan alone, who calls out the absurdity of the alleged divine plan, perhaps it ensures that the lesson will sink in. When even the murderer has had enough, it means that things have gotten way out of hand.

Another telling difference between the kinnah and the Talmudic accounts is its failure to relay the aftermath of the incident. Unlike in the Bavli, here Nebuzaradan does not take responsibility for his actions or convert to Judaism. Likewise, God does not take note of Nebuzaradan’s “mercy” as in the Yerushalmi. In this manner, the kinnah deemphasizes the story’s human actors, focusing instead on God’s relationship with the Jewish people. The paytan suggests that we should not be fooled by appearances. Everything that happened here is God’s work. Nebuzaradan blames God, not Zechariah, because God ultimately decides the appropriate punishment. And whether Nebuzaradan felt remorse and converted afterwards is not important to ha-Levi. Rather, Nebuzardan is a vehicle for conveying a message. He begins as a passive messenger doing God’s will, but ends up as a mouthpiece calling out God for His apparent injustices. For indeed, the kinnah, unlike the Talmudic accounts, is all about the nature of divine justice.

Thus, unlike its Talmudic precedents, ha-Levi’s kinnah confronts, albeit subtly, the thorny issues of theodicy raised by the story. The narrator’s initial approach about guilt and remorse concludes that the punishment was deserved. Yet Nebuzaradan’s confrontation with God carries a different lesson: it is not always sufficient to hit one’s breast and sigh, “Mipnei hata’enu” – “we suffer because of our sins.” Sometimes one also needs to challenge God’s justice.

The Multifaceted Nature of Mourning on Tishah Be-Av

One cannot say for sure why ha-Levi transformed the rabbinic story to address theodicy. Nevertheless, ha-Levi’s version fits with the themes of Tishah Be-Av, as the day’s central biblical text, as well as other kinnot, emphasize that mourning goes beyond just reciting laments; one must also grapple with God’s justice. In the first chapter of Megillat Eikhah, the Book of Lamentations, the narrator (traditionally Jeremiah) begins by acknowledging guilt and proclaiming that God is just. He states, “Jerusalem has greatly sinned; therefore she has become a mockery” and “God is in the right, for I have disobeyed Him” (Lamentations 1:8, 1:18). Yet this traditional piety does not last. At the beginning of the next chapter, the Megillah strikes a different tone, saying that God “bent His bow like an enemy, poised His right hand like a foe; He slew all who delighted the eye. … The Lord has acted like a foe, He has laid waste Israel, laid waste all her citadels, destroyed her strongholds” (2:4-5). As the book progresses, the narrator goes back and forth between submission and confrontation. The very last lines, in fact, challenge God: “Take us back, O Lord, to Yourself, and let us come back; renew our days as of old! For truly, You have rejected us, bitterly raged against us” (5:21-22). Eikhah’s narrator is possessed by questions of theodicy, and does not reach the same conclusion at every moment in the book.

The kinnot are much the same as Eikhah. Some follow the traditional patterns of guilt and remorse: Lekha Hashem ha-Tzedakah, for example, contrasts God’s righteousness and Jewish sinfulness in each stanza. But others, like Elazar ha-Kalir’s Eikhah Atzta be-Apekha, strike a far more accusatory tone: “How could You rush Your wrath, ruining Your loyal people at the hands of Rome, and not remember Your covenant with Abraham, who met the challenge of Your trials?” There is a forceful rhythm to the kinnah; the paytan almost sounds angry. According to Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Megillat Eikhah in fact permits the recitation of kinnot like Eikhah Atzta. Only once we have read the Megillah, in which Jeremiah challenges God, can we do so as well in the kinnot.[11] Tishah Be-Av’s liturgy teaches that in mourning the tragedies of Jewish history, we not only cry, lament, and reflect on sin, but also confront God.

In this manner, Yom Akhpi Hikhbadti’s shift between different responses to tragedy, where confrontation with God follows an initial acceptance of His judgment, adopts the paradigm of Eikhah and other kinnot. Indeed, the kinnah is a particularly good example of Tishah Be-Av’s lack of a single response to questions of theodicy: after Nebuzaradan’s anger suggests that God went too far, ha-Levi returns to focusing on guilt in the concluding stanza: “To You, Lord, we sinned, did wrong, transgressed! We killed Your prophet and knew we did evil!” In the hands of the master poet Rabbi Yehudah ha-Levi, the story of Zechariah’s blood becomes a quintessential Tishah Be-Av lament: the kinnah accepts God’s judgment in one breath, challenges Him in the next, and then comes back full circle to where it began.

[1] I would like to thank Davida Kollmar and Ted Rosenbaum for their insightful feedback on this article.

[2] The story appears once in the Talmud Yerushalmi (Ta’anit 4:7), once in Pesikta de-Rav Kahana (15), twice in the Talmud Bavli (Gittin 57b and Sanhedrin 96b), twice in Kohelet Rabbah (3:16, 10:4), three times in Eikhah Rabbah (Petihta, 2, 4), and twice in Yalkut Shimoni (364, 1027). Richard Kalmin, in Migrating Tales: The Talmud’s Narratives and Their Historical Context (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2014), also identifies non-rabbinic versions of the story in Christian and Islamic sources, and he speculates that the extant Jewish and non-Jewish versions of the tale arose out of earlier common sources, perhaps Christian ones. Ibid., pp. 139-40, 142-46, 155-60, 161-63.

[3] Kalmin casts doubt on the identification of Zechariah in the rabbinic story with Zechariah ben Jehoiada in Chronicles. Ibid., pp. 135-37, 141, 152-60. Nonetheless, medieval Jews commonly assumed that the story’s Zechariah is the Zechariah in Chronicles (e.g. Rashi Gittin 57b, s.v. shel zekhariah), and that assumption persists today.

[4] See Kalmin, pp. 132-33.

[5] Kalmin suggests that in an earlier version of the story that is not extant but was reworked into the version now appearing in the Yerushalmi, Nebuzaradan does not address Zechariah, and God stills the blood unprompted. This hypothesized version suggests that Israel’s sins were too terrible to be forgiven; when the Israelites killed Zechariah, who was a prophet, he could no longer intercede on their behalf. Only God could end the tragedy, and he does so only out of mercy for His prophet, not out of mercy for His people (ibid., pp. 137-41). This version of the story might reveal a different, even less hopeful approach to theodicy that accepts the possibility of divine abandonment. However, all of the versions we have today contain a line in which Nebuzaradan speaks to Zechariah, implying that Zechariah still has a voice and that the Israelites can still be forgiven through the intercession of their prophet.

[6] Or, “caused a rift in his family.” Kalmin, p. 149.

[7] See ibid., pp. 151-152.

[8] I have relied upon the text of the kinnah in Daniel Goldschmidt’s critical edition. Daniel Goldschmidt, Seder Ha-Kinnot Le-Tishah Be-Av (Jerusalem: Mossad HaRav Kook, 1952), pp. 120-22. This version is also largely used by Koren. Goldschmidt’s version contains some lines that are absent in many printed editions of the kinnah, including a critical one about the blood resting, but also omits some material present in other versions. Goldschmidt also notes variant texts. For the English translation of this kinnah and others, I have largely relied on Tzvi Hirsch’s Weinreb, The Koren Mesorat HaRav Kinot (Jerusalem and New York: Koren Publishers and OU Press, 2011).

[9] In many printed editions of the kinnot, this line appears toward the end of the kinnah. In Goldschmidt’s edition, however, it appears right after Nebuzaradan begins to investigate the origins of the bubbling blood.

[10] Some versions of the rabbinic story suggest, like the kinnah, that Nebuzaradan’s avenging role was preordained and that the Jews were resigned to this fact. In Kohelet Rabbah, when Nebuzaradan arrives, God tells Zechariah, “Now it is time for your cause to be collected,” and God makes the blood start bubbling. This is practically an invitation for Nebuzaradan to act, and it emphasizes that his role was preordained. Further, in the Yerushalmi and some of the other midrashic versions, the Jews decide to tell Nebuzaradan about Zechariah’s murder in part because they realize that “God wants to claim his blood from our hands.”

[11] See Joseph B. Soloveitchik, The Lord is Righteous in All His Ways: Reflections on the Tish’ah be-Av Kinot, Jacob J. Schacter, ed. (Brooklyn, NY: Ktav Publishing House, 2006), 86-97. For Rav Soloveitchik, this allowance is highly circumscribed; it begins once the Megillah has been read and ends with the last kinnah; it does not extend to the rest of the year. Ibid., p. 89. Yet Rav Soloveitchik’s view is not the only one, and the question of rabbinic attitudes toward the propriety of confronting God is admittedly complex. See generally Dov Weiss, Pious Irreverence: Confronting God in Rabbinic Judaism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017). Weiss argues that while the Tannaim generally opposed it, later Amoraim and Geonic-era midrashim took a far more favorable view. Ibid., pp. 22-87.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.