David Block

“How is this year different from all other years?” The answer is not too hard to muster. For most of us, it will be extremely challenging. Many will be without extended family and friends at our holiday tables, without conversations in shul about whose Seder went the longest, without Yizkor for a lost relative, without the communal element of the hag which usually animates the holiday and illuminates its depths.

I read something recently that struck a chord deep within me. In With God in Hell, R. Eliezer Berkovits highlights concessions that concentration camp inmates had to make regarding their Pesah observances, and it immediately had me thinking about our current circumstances.

Before I continue: I am very hesitant to mention the Shoah in the context of another crisis. To be clear: I’m not at all suggesting that the trials of the current situation are in any way akin to what those who went through the Holocaust faced (they obviously are not). I simply invoke the experiences of those concentration camp inmates because I learned something from them that allowed me to reframe my mindset heading into this Pesah.

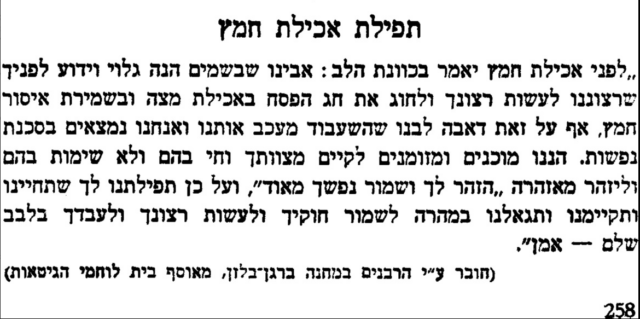

Needless to say, matzah was hard to come by in the camps. And eating bread during Pesah was not just halakhically allowed, but absolutely necessary; their very lives depended on it. And yet, even as the religiously observant among them must have felt profound disappointment with their inability to keep the laws of Pesah, many took the opportunity to infuse their lack of action – or, what would otherwise be “transgressive” action – with religious meaning. Before they ate their hametz, where they would have normally said a “הנני מוכן ומזומן (I am ready and prepared to fulfill the mitzvah…)” prayer before fulfilling the mitzvah of eating matzah, they said the following Tefilah, composed by a number of rabbis in Bergen-Belsen:

“Our Father in Heaven! It is open and known before You that it is our will to do Your will to celebrate the festival of Pesah by eating matzah and refraining from leavened bread. With aching hearts we must realize that our slavery prevents us from such celebration. Since we find ourselves in a situation of Sakkanat Nefashot, of danger to our lives (should we not eat this bread), we are prepared and ready to fulfill Your commandment, ’And thou shalt live by them (by the commandments of the Torah), but not die by them’; and we are warned by Your warning, ‘Be very careful and guard your life.’ Therefore we pray to you that You maintain us in life and hasten to redeem us that we may observe Your statutes and do Your will and serve You with a perfect heart. Amen!” (Trans. Berkowitz, p. 32)

Here is the original Hebrew, found in historian Mordechai Eliav’s Ani Ma’amin (special thanks to Dr. Moshe Shoshan for helping me track it down):

אבינו שבשמים הנה גלוי וידוע לפניך שרצוננו לעשות רצונך ולחוג את חג הפסח באכילת מצה ובשמירת איסור חמץ, אף על זאת דאבה לבנו שהשעבוד מעכב אותנו ואנחנו נמצאים בסכנת נפשות. הננו מוכנים ומזומנים לקיים מצוותך “וחי בהם ולא שימות בהם” וליזהר מאזהרה, “הזהר לך ושמור נפשך מאוד,” ועל כן תפילתנו לך שתחיינו ותקיימנו ותגאלנו במהרה לשמור חוקיך ולעשות רצונך ולעבדך בלבב שלם – אמן

Instead of focusing on the mitzvot they could not fulfill, they looked to the one that they could: that of protecting and guarding human life. This religious commitment and focus – reminiscent of the story of R. Elimelekh and R. Zusha, who are reputed to have rejoiced in their ability to keep the Halakhah not to pray in the vicinity of a prison latrine, despite their painful inability to fulfill the mitzvah of prayer – is nothing short of breathtaking.

Thank God, most of us are in a position such that we do not have to compromise on any of the biblical laws (or even rabbinic restrictions and customs) of Pesah. Still, as we are set to begin a holiday bereft of some of the elements that are core to our celebrations – family, shul, Yizkor, inviting those less fortunate to spend the Sedarim with us – it is natural to feel sadness and disappointment. I think it’s okay to feel that, to “mourn” the loss. But I also wonder if it’s worth reframing our thinking by shifting from the sadness of what we aren’t doing to the simhah, joy, of what we are doing in its stead. In that spirit, I offer the following adaptation of the holy tefillah originally composed in Bergen Belsen. Hopefully, our inability to fulfill certain elements of Pesah due to our extreme care for health and life can also be experienced through a lens of religious meaning.

Our Father in Heaven! It is open and known before You that it is our will to do Your will to celebrate the festival of Pesah with our communities, families, and friends, to pray and recite Your praises together with our communities, to have an intergenerational conversation about the story of the Exodus, to take care of the elderly, to sincerely invite those less fortunate to partake of the Seder with us, as the Haggadah says, “Anyonewho is hungry – come eat, anyone who is needy – come and partake of the Pesah offering.” With aching hearts we must realize that the current precautions around the COVID-19 pandemic prevent us from such celebration, since we find ourselves in a situation of sakkanat nefashot, of potential danger to our lives. Therefore, we are prepared and ready to fulfill Your commandment, “And you shall live by them (by the commandments of the Torah), but not die by them,” and we heed Your warning: “Be very careful and guard your life.” Therefore we pray to you that You maintain us in life and hasten to redeem us that we may observe Your statutes and do Your will and serve You with a perfect heart. Amen!

אבינו שבשמים הנה גלוי וידוע לפניך שרצוננו לעשות רצונך ולחוג את חג הפסח עם קהילתנו ומשפחתנו וחברינו, להתפלל ולספר תהילתך בציבור, לספר את סיפור יציאת מצרים בשיחה בין-דורית, לטפל בזקנים, להכריז בלב שלם: “כל דכפין ייתי וייכל, כל דצריך ייתי ויפסח.” אף על זאת דאבה ליבנו שהמגיפה מעכבת אותנו ואנחנו נמצאים בסכנת נפשות. הננו מוכנים ומזומנים לקיים מצוותך “וחי בהם ולא שימות בהם” וליזהר מאזהרה, “השמר לך ושמור נפשך מאוד,” ועל כן תפילתנו לך שתחיינו ותקיימנו ותגאלנו במהרה לשמור חוקיך ולעשות רצונך ולעבדך בלבב שלם. אמן

[A Closing Note: In sharing these thoughts with R. Yitzchak Etshalom, a master paytan and Hebrew linguist, he too was moved by this idea and composed two beautiful tefillot that touch upon the same themes (both more eloquent and original than my above adaptation). While the above tefillah is meant to frame the holiday experience in general, R. Etshalom’s are intended to be inserted at two different parts of the Seder, to help infuse Maggid and Hallel with special meaning. You can find his tefillot here.]

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.