Jeremy Brown

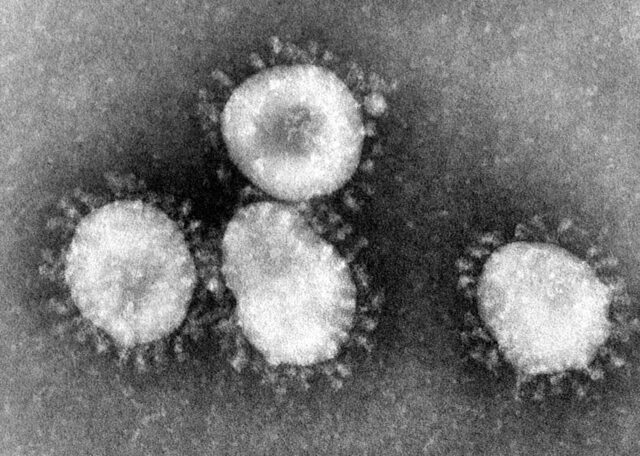

The news of the spreading new coronavirus is worrying. Borders have been closed, flights cancelled, and travelers from China quarantined. Currently, the best medical advice is the same we have given for decades to combat seasonal influenza: cover your face when you sneeze, wash your hands, and stay at home if you don’t feel well.

In the last century there was, however, a particularly Jewish response to a life-threatening epidemic. It was known in Yiddish as the Shvartze Chassaneh, the Black Wedding, and took place in response to the terrible waves of cholera, typhus, and influenza that ravaged the Jews of Eastern Europe, Israel, and North America.

The ceremony was simple: a man and women, each unmarried and either impoverished, orphaned, or disabled (sometimes all three) were married together as husband and wife under a huppah – in a cemetery. The couple’s new home was established with donations by the community. With this act of group hesed, it was hoped that the plague would be averted.

For example, one such ceremony took place 101 years ago, as the Jews of Philadelphia gathered in a cemetery with the goal of defeating the deadly influenza outbreak. By the time it was finally over, the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918-1919 claimed 50-100 million lives worldwide. In the U.S. over 670,000 people died, and the dead were piling up in the city of Philadelphia.[1] And so the Jews there celebrated a Black Wedding.

According to newspaper reports, they chose Fanny Jacobs and Harold Rosenberg as their bride and groom. The two were married at the “first line of graves in the Jewish cemetery” near Cobbs Creek at 3pm on Friday October 25, 1918. More than a thousand Jews watched as Rabbi Lipschutz officiated at the huppah. “And when amid their stark surroundings,” the report continued, “the couple were pronounced man and wife, the orthodox among the spectators filed solemnly past the couple and made them presents of money in sums from ten cents to a hundred dollars, according to the means and circumstances of the donor, until more than $1,000 had been given.”[2]

The Jewish community had chosen this intervention so that “the attention of God would be called to the affliction of their fellows if the most humble man and woman among them should join in marriage in the presence of the dead.” An odd choice for today perhaps, but not as odd as it might seem given the reality of life during the Great Flu Pandemic. Today we know that influenza is caused by a virus, but in 1918 viruses had not been discovered. We now know that influenza is transmitted by droplets; back then, there was no such notion. We now have antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial pneumonias, but these would not be discovered for another three decades. A century ago there were many theories as to the cause of influenza, whose very name points to its presumed etiology. It comes from the Italian word meaning influence, because it was believed that the disease was caused by an inauspicious alignment of the planets. There were other suggestions too. The famous seventeenth-century English physician Thomas Sydenham believed these epidemics were related to heavy rains that filled the blood with “crude and watery particles.”[3] Following a devastating outbreak of influenza in the winter of 1889 there were rumors that the epidemic had been brought to Britain by imported Russian oats, which were eaten by horses who then spread the infection into the human population. Other theories of origin included rotting animal carcasses, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and effluvia discharged into the air from the bowels of the earth.

In truth, no one had a clue what caused influenza, and without an obvious etiology, people suggested all kinds of cures. Some used organic remedies: burning orange peels or dicing onions to sterilize the room. Others recommended a tea-spoonful of Friar’s balsam, a small handful of eucalyptus leaves, or tonics containing quinine. (Grove’s Tasteless Chill Tonic was especially popular, and made the Grove family fantastically rich). All physicians prescribed laxatives for their patients, and most suggested alcohol. “There is no finer pick-me-up after an attack of influenza,” wrote one American physician, “than good ‘fiz.’” Britain’s Chief Medical Officer suggested half a bottle of light wine daily.

Some physicians resorted to bloodletting, the practice of draining the body of blood, and therefore, in theory, of toxins and disease. It had been a mainstream medical practice for more than two thousand years. The procedure is frequently described in the Talmud, which mandated a blessing to be made before it was undertaken. In 1918 British doctors had performed bloodletting on ailing servicemen. They claimed it had worked, and published their experience in the British Medical Journal. We look back in horror, but at the time it was cutting-edge science.

Regardless of whether they believed in the treatments they were prescribing, physicians certainly understood the importance of maintaining morale in the face of the pandemic. “It is our duty,” said Chicago’s health commissioner that winter, “to keep the people from fear. Worry kills more people than the epidemic. For my part, let them wear a rabbit’s foot on a gold watch chain if they want it, and if it will help them to get rid of the physiological action of fear.”[4] Which is precisely what the Jews of Philadelphia did on that cold October afternoon. But instead of carrying a rabbit’s foot, they made their way to the Cobbs Hill cemetery.

Although its origins are entirely unknown, the Black Wedding had been imported from Eastern Europe, where it had been practiced since the eighteenth century. The earliest recorded Black Wedding was performed in 1785 in the presence of one of the great founders of the Hasidic movement, Rabbi Elimelich of ּּLizhensk. It took place in response to an outbreak of cholera. The bride was a thirty-six-year-old villager and the groom a thirty-year-old water carrier, and despite their humble situation, the wedding was attended by other Hasidic leaders including the famed Seer of Lublin.[5]

Black Weddings took place in both Safed and Jerusalem in 1865 following another natural disaster: a massive plague of locusts that had destroyed the crops and resulted in the deaths of many hundreds. An eyewitness account reported that “the leaders of that holy city took boys and girls who were orphans and married them off to each other. The huppot were in a cemetery between the graves of our teacher the Ari z”l [Rabbi Isaac Luria Ashkenazi] and the Beit Yosef [Rabbi Yosef Karo]. For this was a tradition that they had, and thanks to God who removed this deathly outbreak from among them.”[6] The wedding in Jerusalem took place on the Mount of Olives, “was attended by many, and was a very joyous occasion.”[7] There are newspaper reports of similar ceremonies in Berdichev in northern Ukraine in 1866, Opatow, Poland in 1892, and in the small Ukrainian village of Olyka, which suffered from a typhus epidemic, as human and animal corpses were left unburied on the battlefields of World War I.

The Black Wedding in Philadelphia during the Great Influenza Pandemic was not unique to the Unites States. Two weeks later, on Monday, November 11, the ceremony was performed in Winnipeg, Canada. Under the headline “Hebrews Hold ‘Wedding of Death’ to Halt Flu,” a local newspaper reported that the elaborate wedding had been planned for more than a month. “At one end of the cemetery a quorum of ten Jews conducted a funeral. At the other, 1,000 Gentiles and Jews witnessed the wedding… Harry Fleckman and Dora Wisman were contracting parties at the wedding. Rabbis Khanovitch and Gorodsy officiated.”[8] And Odesskiye Novosti, a Ukrainian newspaper, described a Black Wedding that had been arranged “in order to contain the two epidemics raging in Odessa – the Spanish flu and cholera.”[9]

In the early nineteenth century and in response to their own outbreaks of cholera, towns from Massachusetts to Kentucky had observed a public day of fasting and prayer “by designation of the civil authorities.”[10] With no notion as to the cause of the illness, no way to prevent its spread, and no medications to alleviate the suffering, it is little wonder that the Jewish communities turned to folk medicine and married off poor orphans in a Black Wedding. For really, what else was there to do?

As we wait to see how far the current coronavirus outbreak spreads, we should pause and reflect on our good fortune. We now understand the etiology and can often conquer those diseases that were mysterious and life-threatening to our great-grandparents. Vaccines, public-health interventions, and antimicrobial drugs generally keep us safe. And, in the face of an epidemic, we no longer need to gather at the local cemetery and marry off a destitute couple in order to invoke God’s mercy.

[1] Jeremy Brown. Influenza: The Hundred-Year Hunt to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History. Simon and Schuster 2018.

[2] Public Ledger of Philadelphia, October 21, 1918.

[3] Brown, Influenza, 32.

[4] G. M. Price, “Influenza—Destroyer and Teacher,” Survey 1918. 41 (12): 367–369.

[5] Avraham Chayim Michelson, Ohel Elimelech. Przemysl 1910, 66.

[6] Moshe Nussbam, Sefer Sha’arei Yerushalayim. Warsaw, Shmuel Earglbrand, 1868, 39b.

[7] Eliyahu Porush, Zikhronot Rishonim, Jerusalem, 1963.

[8] Winnipeg Evening Tribune, November 11, 1918.

[9] Odesskiye Novosti, October 2, 1918.

[10] The American Quarterly Register, November 1832. Vol. 5(2), 97.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.