Josh Rosenfeld

ב״ה

It is 1922… I am in Jerusalem, basking in the shade of the Rav in his Beit Midrash, day and night. The day came, and I arose to ask him: Our master, there is holiness here with you, a special spirit. Is there a central teaching as well? A specific message, a unique approach? The answer: Of course there is. From that day on, I decided to clarify the teachings of the Rav as a complete, organized Divine message, its foundations, and the foundations of those foundations, and to thereupon organize and write them down… and the Divine message that emerged: all-encompassing holiness, the spirit of the world, the unification of all things, all-encompassing goodness, elevation of this world.

(Introduction of R. David Cohen, ha-Rav ha-Nazir, to Orot ha-Kodesh of R. Kook)

?

“What am I holding here?

– My right hand.

And what am I holding here?

– My left hand.

And what is the advice of Reb Nahman of Breslov?”

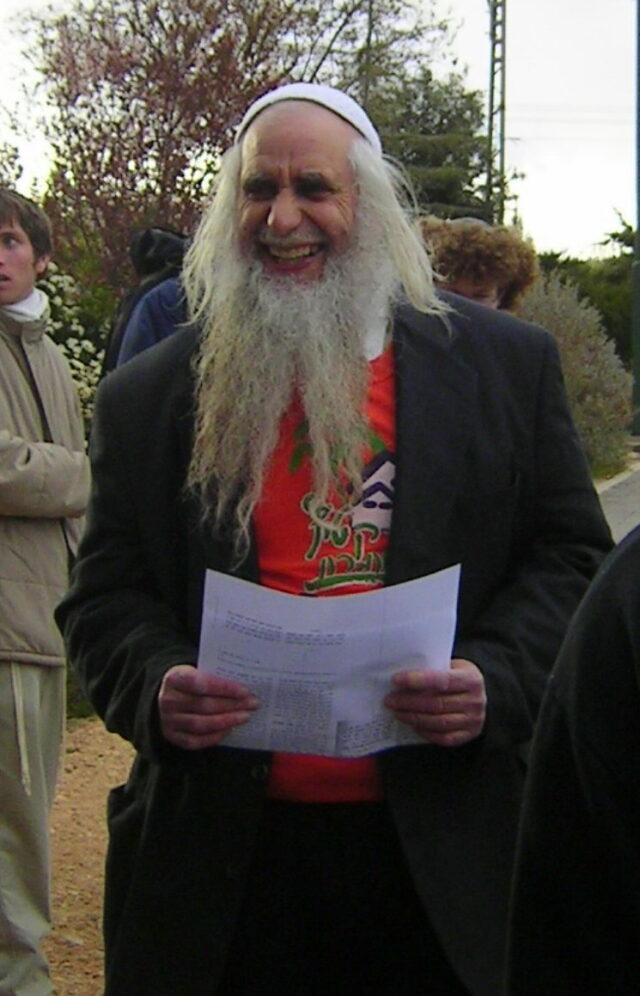

The man asking these questions seems out of place, adorned with a white spudik and white kapute on a huge stage with the slogan “We remember the murder. We fight for democracy” emblazoned on the screen behind him. His flowing white beard and peyot are almost missed for the benevolent, wise smile across his face. One might be forgiven for thinking, is this some sort of joke?

The smiling, laughing man on stage is very serious. So are the thousands of people clapping along with him, as the camera pans to the crowd. The setting is Rabin Square, and the gathering is a rally commemorating the murder of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

“[We] must bring The Left and The Right into contact.

[more clapping]

[We] must bring Jews and Arabs into contact.

[more clapping]

Rabbeinu Nahman of Breslov also said: ‘There is no such thing as giving up hope!’

Let’s clap hands for the chance of peace [repeated in Arabic].

Sha-lom.

Sha-lom.

Sha-lom.

– Peace between the side of me that loves my people, and the side of me that loves every human being…”

The man delivering this powerful lesson (based on Likkutei Moharan I:45) in this powerful context is Rabbi Menachem Chai Shalom Froman (1945-2013), may his memory be a blessing. Rebbe Menachem, as some called him affectionately, was many things during his 67 years here. A poet, peace activist, mystic, community Rabbi, soldier, father, and husband. It was the many threads of humanity woven into this unique rabbi that made him into a figure both beloved and scorned during his life and after. Rebbe Menachem was something of a paradox, occupying roles and espousing positions that confounded those who sought to understand who he really was. For his part, Rebbe Menachem seemed most at peace living his life within these gray areas, comfortable in the contradictions that appeared to resolve themselves within his soul. He was, to use the language of the Zohar which he loved and so passionately taught throughout his lifetime, the secret of all things gathering together as one (Zohar Terumah, 2:135a).

?

Menachem was born in Kfar Hasidim, June 1st 1945, to Leah Raizel and Yehuda Aryeh Froman. His father came from a family that traced its roots to Poland, something that his son would later cite as the background for his unusual style of rabbinic levush, an Eretz Yisrael riff upon the traditional black dress of the Gerrer Hasidim. He had a secular upbringing and was a member of Labor Zionist youth groups. He served as a paratrooper in the IDF and took part in critical battles during the Six Day War. After the war, he drew closer to observant Judaism while studying at the Hebrew University, eventually moving on to learn at the flagship Religious Zionist Yeshivat Merkaz ha-Rav. Although he spent a year living in the house of the Rosh Yeshiva, R. Zvi Yehuda ha-Kohen Kook, it is told that at the outset of his time there he slept in a sleeping bag, refusing to fully enter the dormitories until he felt his process of repentance was more complete.

The newly ordained Rav Froman moved on to become the Rabbi of Kibbutz Migdal Oz, and taught in several Religious Zionist institutions. He later joined R. Adin Even-Yisrael Steinsaltz and R. Shimon Gershon Rosenberg (Shagar) in teaching at Yeshivat Mekor Chaim. While the Yeshiva, also referred to as “SheFA” (an acronym of S’hagar, F’roman, A’din), was short-lived, the distinctly Israeli version of hasidut that permeated it went on to have major cultural effects across the Jewish world. R. Dov Zinger, leader of the Mekor Chaim High School today and a friend-student of all three aforementioned rabbis, described the atmosphere there:

Rav Shagar, Rav Steinsaltz, and Rav Froman were on the one hand entrenched in hasidut in its deepest sense – cleaving to God and a very exacting way of life. Yet on the other hand, it never devolved into ‘hunyuki’ut’ (=overly pious), rather it was expressed in a great sense of freedom. This was true of the way in which the rabbis interacted with each other – it was always direct, open, free of pretension, and also of the learning: it was possible to speak of everything, the questions in their proper place without fear; it was possible to expose oneself to literature and philosophy. It was a very unique approach, that engendered strength and freedom amongst the students.

Rav Froman became the rabbi of the Tekoa settlement in Gush Etzion, a position he would hold for the rest of his life. He would also go on to teach in Yeshivat Otniel. Rav Froman married Hadassah, an artist and spiritual teacher in her own right and together they would have 10 children, some of whom work to perpetuate their father’s singular legacy. Rav Froman passed away after a long illness at the age of 67.

R. Elhanan Nir, a foremost student of R. Shagar and a rosh metivta in Yeshivat Siach Yitzchak (founded by R. Shagar and R. Yair Dreyfuss), relates that at the funeral of R. Shagar, Rav Froman got up to speak about his close friend. R. Nir, writing after Rav Froman’s own funeral, observes that the same words are as true of Rav Froman himself:

R. Shagar was in my eyes the materialization of the promise that lies in R. Kook’s teachings… Our community holds close many ideals of The Rav, like Eretz Yisrael, the state, the army, the redemption of Israel, but in my eyes the main thing in Rav Kook’s teachings is the illumination of the religious world with the light of freedom. The main thing is the free expression in which one lives their religious lives. R. Shagar actualized this – not in the sense of ‘intellectual freedom’, but rather in a sense of deep spiritual freedom, like a person whose entire soul flows this way. This radiated onto his students, and this, to my knowledge, is the source of all the classic elements of religion, as it is with the students of R. Kook.

Although he did not write much, a posthumous collection of Rav Froman’s aphorisms and short teachings are published in a book called Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh. Levi Morrow, a scholar of R. Shagar, and R. Ben Greenfield have recently finished a translation of this book, and some of their work can be found at the facebook page “Making Hasidim Laugh”. Another book, Sohkei Eretz, contains essays and opinion pieces published in various outlets during his lifetime. A third, Ten Li Z’man, presents several essays arranged according to the Jewish calendar. There are also two collections of his poetry, Adam min ha-Adamah and Din v-Heshbon al ha-Shiga’on, the latter of which served as the basis for an album of music called Kanfei Ruah. Despite his significance for Religious Zionism in Israel, American audiences have relatively scant exposure to Rav Froman, although some posthumous appreciations have been penned for English speakers. In truth, the best way to experience Rav Froman’s teachings and personality is through watching and listening to him, and many of his classes are available online.

This would all seem like a relatively standard biography of a Religious Zionist rabbi and leader. Yet, along the way, Rav Froman broke every mold of what people might assume that to be. He transitioned from the fiercely nationalist Gush Emunim bloc to a political ideology that found him meeting with Hamas leader Sheikh Yassin, Yasser Arafat, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. He issued statements declaring his willingness to work toward the formation of a Palestinian state, so long as he could live upon his beloved land as its citizen. Rav Froman believed that the foundation of the Israeli-Arab conflict rested upon religion, and that interfaith dialogue was the key to its resolution. To that end, he drafted a peace agreement together with a prominent Palestinian journalist, and functioned as one of the leaders of the Eretz Shalom peace movement. All of this while serving as the rabbi of a large settlement, and deeply steeped in the ideology of ‘Greater Israel’. Yossi Klein Halevi, the journalist and author who underwent a similar trajectory in his own life, writes in his memoir At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden,

For Froman, promoting Muslim-Jewish dialogue was part of the same messianic commitment that had led him to settle the West Bank. This was, after all, the age of miracles. If the Jews had been replanted in the biblical land, just as the prophets had predicted, then surely the prophets’ vision of peace between Israel and the nations was also within reach. And the most urgent place to begin was healing the ancient feud between Isaac and Ishmael.

What am I holding here?

– My right hand.

And what am I holding here?

– My left hand.

And what is the advice of Reb Nahman of Breslov?

[joyous clapping]

For all this, Rav Froman found himself the focus of sustained criticism, even death threats. In her subtly fictionalized narrative of her parents lives, Shemonah Dakot Ohr, his daughter, Liharaz Tuitto-Froman, describes how their home was repeatedly daubed with graffiti and how her father was publicly cursed in Tekoa’s synagogues. At the same time, Rav Froman’s boundless love drew near to him people from all walks of Israeli life – spiritual seekers – deeply observant and not at all. Towards the end of his life, this broad soul would lead evenings of Torah and music, teaching Zohar and Rebbe Nahman accompanied by some of Israel’s famous musicians who saw him as their Rebbe.

– Peace between the side of me that loves my people, and the side of me that loves every human being

While the public image and acceptance of Rav Froman has softened somewhat since his passing, the radical way in which he lived, thought, and taught has not.

?

Despite the intensity and revolutionary arc of Rav Froman’s life and teachings, he sought to articulate it all through an unbearable lightness of being:

Many years ago, I suggested to my wife that we change our surname from ‘Froman’ to ‘Purim’. Instead of people saying: “Rabbi Froman met with Arafat, he met with Hamas etc.”, they’ll say “Rabbi Purim”. This way, it’ll sound totally different. No one will take anything I do too seriously…”

(Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh, no. 27)

This is not to say that Rav Froman didn’t take himself seriously, but rather it is to be understood as an expression of his characteristic humility and hasidut. In Shemonah Dakot Ohr (p. 183), his daughter relates that he was an exemplar of the rabbinic dictum (Midrash Tehillim on Psalms 16) that “anyone who is cursed and is silent… is called a hasid”:

He was always silent. She did not remember even one time where he issued a rejoinder or tried to defend his honor, nor did he depart when he would be screamed at. He sat and listened. To some, it seemed that he was indifferent, as if a clear line separated him and the rest of the world, as if all the deliberations about him passed by and never entered his psyche. She knew this wasn’t true, instead, of course he would be embarrassed and internalize it. Nor was this the main point. The main thing was that he found the opposition useful. It allowed for him to take a full accounting of himself (= heshbon nefesh), to scrutinize his ways again and again… And if he decided to proceed apace, the opposition was that which gave him the individual strength to do so, to go against the stream and to act from a place devoid of any desire for honor or public appreciation, but rather only because he believed that this was what his Creator wanted of him.

Rav Froman once said that part of his work was to “purify religion”, and clarified that he was referring to “idolatry, egotism… we come from dust and will return to dust.” This abiding humility is perhaps what allowed for such a drastic ideological trajectory in life. It represents the ability to reconsider one’s positions and allow for an epistemological uncertainty to inform how new ones are formed. It is this humility which allowed for Rav Froman’s fundamental openness, especially in the areas of faith and learning Torah. His son, R. Yosi Froman, relates (Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh, no. 85) that “in truth, this was a great matter for him, which he repeated often in his talks and especially in his actions: that faith should not turn into close-mindedness.”

Learning Torah was to be an act rooted in humility and openness as well. Rav Froman would often finish teaching Torah and wonder out loud (Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh, no. 130): “what did I do here today? Did my learning take me out of myself, and open me up to God? Maybe it was just to inflate my ego… something more to put in the bag of accomplishments?” Similarly, he taught (Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh, no. 134) that when Rebbe Nahman of Breslov taught that Torah should be learned with force (= koah; Likkutei Moharan I:1), the intent was that one must nullify themselves and their baseline assumptions about the world and give themselves over to listen intently to what God was saying through the text. More bluntly put, Rav Froman wholeheartedly “refused to celebrate in the celebration of self”.

The continual act of opening oneself up and letting down intellectual and egotistical defenses is what fostered the deep sense of freedom – intellectual, spiritual, personal – that lies at the center of Rav Froman’s message. In one of his most heartfelt poems, he cries out:

Freedom, freedom, don’t stop a thing. Don’t suppress anything. Wear one form and another.

Arrive at one place and then another, flowing in every direction.

Where has my strength gone?

Look, I’ve lost my form. I haven’t reached anything. I’m spilled into the void.

Exhaustion casts its net over me. My time is over.

Is there some other horizon as deep and free as this?

(Din v-Heshbon al ha-Shiga’on, p. 35)

Here is a bouncing soul, running and returning from the wide open expanses of freedom to a depressingly empty realization of mortality. And yet, even in that abyss of mortality is to be found yet another avenue to freedom. It is a cry from a man defined by his search for some lasting, true encounter with the Divine. With the sense of mission and dedication to the people and the land he loved that defined his life, it is no wonder that we find Rav Froman on his deathbed, singing along with his wife Rabbanit Hadassah to the words of Yoram Toharlev’s You Are the Land to Me with tears streaming down his face: “give me time, give me time, together we shall reveal the land.” There, he issued the following lesson: “In my eyes, religion means to live with death. To live with the illnesses and to live with suffering. To live with reality as it is.” Rav Froman taught that the way to do this, or at the very least, the way he did this was with laughter (Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh, no. 116): “The truth is that the world is filled with tragedy. Reality is filled with myriad inner contradictions… and I overcome them through humor.” This is possible when one recognizes that the most serious thing of all is connecting with God, deveykut, and that all other considerations are cut down to size in the face of that goal.

Rav Froman was a man of paradoxes who sought his whole life to reconcile and unify them in the wide open expanses of spiritual freedom. He did so through a fundamental rootedness in love for his land (Rav Froman would often remove his shoes when teaching Torah, “to connect to the Holy Land” beneath him), his family, his people, and for the entire world. It was also anchored in an unusually exacting observance of and reverence for Halakhah, sometimes to the amusement of those who observed it. His daughter relates that it was his practice to go from shul to shul in Tekoa to try to hear as many blessings of the Kohanim as possible in a given day. All of this serious work was accomplished with a lightheartedness – never lightheadedness – and a sense of profound faith.

There are things in life that are indeed big and important, in which the only way to grasp onto them is through laughter. By laughing at them, we also accord them their due respect. This is necessary, because if you try to grasp the thing itself, you run the risk of making it small, rendering it banal. The laughter that opens up the learning is like a handle, that only through it can we raise a boiling pot…

We all are going to die. What can we do in the face of such a heavy, incomprehensible fact like this? Laugh. Laughter is the way to grasp onto death itself.

(Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh, no. 111)

To answer the question we began with, yes, this is some sort of joke. It is the most ‘inside joke’ possible, a laughter within one man’s soul as he is continually shocked awake and moved to action by the absurd world he finds himself in. Hasidim Tzohakim mi-Zeh, the righteous laugh at this. It is a world as contradictory and paradoxical as the one within his soul, and in seeking to bring peace to that world, he is seeking to bring peace to himself as well, knowing that it is forbidden to give up hope.

Sha-lom.

Sha-lom.

Sha-lom.

[joyous clapping]

?

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.