David Zvi Kalman

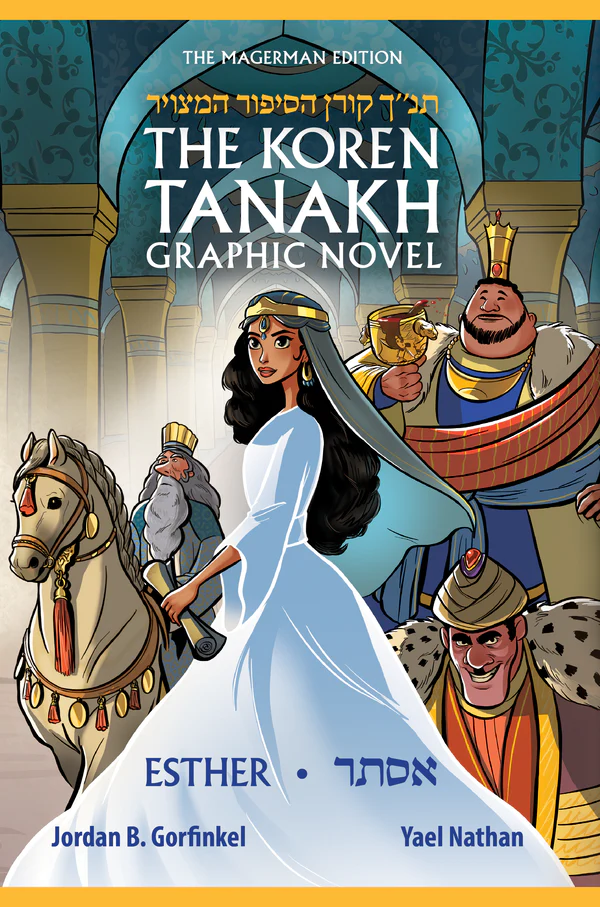

Review of Jordan B. Gorfinkel and Yael Nathan, The Koren Tanakh Graphic Novel: Esther (Koren Publishers, 2023)

I want to start this review by warning you that I am going to do something very unfair, which is that I am going to review a new graphic novel version of Megillat Esther—a book that was clearly designed for children—as though it were written for adults.

There are two reasons for this. The first is that I can, because nobody knows what a kids book is supposed to look like. Maurice Sendak famously said that he was only a children’s book author because other people told him he was. Shel Silverstein chose author photos for his books that seem intentionally designed to terrify children into wondering whether they were actually reading a murder mystery. And graphic novels, despite being descended from comics, have always had a dark streak; the two most important entries in the genre are Spiegelman’s Maus and Eisner’s A Contract with God.

The second reason is that we’re at a moment in Jewish history when illustrated sefarim like this deserve to be treated as more than a spoonful of sugar. As I have argued indirectly on this website and directly on my own, the only reason that text has been the sole vessel for sacred ideas is that text was the only thing a displaced people could reliably transmit. This just isn’t true anymore: Digital data storage can hold text, audio, or video with equal ease, and printers don’t care if the output is words or images. In an era where pictures are more than just a luxury, we need to start taking them seriously. Specifically, we need to start taking them seriously as a form of commentary.

But what kind of commentary? As I paged through Jordan Gorfinkel and Yael Nathan’s masterful illustrations, I kept coming back to this question. Not Nahmanides, certainly; a Nahmanidean graphic novel would likely have overlaid the actual story of Esther with a multitude of aggadic and mystical allusions, perhaps to the point where the original story was no longer visible (JT Waldman’s Megillat Esther is much closer to this style.) Nor was this an Ibn Ezra-style effort to extract both historical and philological accuracy from the text; indeed, I didn’t get the sense that the artists got particularly hung up on making sure that their depictions of Aḥashverosh’s palace or the characters’ vestments were particularly accurate.

Instead, Gorfinkel and Nathan’s work is something like Rashbam inflected with bits of Rashi. Rashbam’s commentary is famous for its brevity and commitment to the plain meaning of the text, to pshat. Rashi, meanwhile, felt much more comfortable drawing in rabbinic source material, so that the reader might see the Bible as the rabbis saw it. In addition, his experience with the Crusades led him to view the source text through the lens of Jewish persecution. This graphic novel’s commitments are clearly to the plain meaning of the text, but it interrupts this occasionally to offer an idea that goes beyond it, especially those ideas that involve Jewish vulnerability.

Let me give an example. As many children know, Haman does not appear in the story of Esther until the beginning of the third chapter. In the first chapter, however, King Aḥashverosh is advised to severely punish his then-queen Vashti by one Memukhan, who the rabbis identified as Haman by another name. Gorfinkel and Nathan clearly liked this idea, and so the last time we see Memukhan he is putting on a new hat that looks very much like a hamantaschen. When Haman arrives in chapter 3, he is depicted with the same hat—but Memukhan’s flowing beard and facial hair have been replaced by an instantly recognizable toothbrush mustache. An elegant insertion of and solution to a textual problem, and not the edition’s only overt reference to the Holocaust.

Something similar takes place in the depiction of Aḥashverosh’s well-adorned palace, which the rabbis understood to have been festooned with artifacts stolen from the Temple. There, behind the king’s throne, we see the famous menorah perched haphazardly in a Scrooge-McDuck-style pile of gold. The king himself wears the high priest’s breastplate as just another bit of glitz.

Allusions to moments of Jewish violence are interspersed in the text, as well. The Megillah’s brief mention that Haman is an Agagite (Esther 3:1)—suggesting that he descends from the king of the Amalekites—leads the artists to create a one-panel synopsis of the Amalekite attack on the Israelites as described in Exodus 17. Haman’s depiction of the Jews as a people “who do not obey the king’s own laws” (Esther 3:8) is accompanied by caricatures of long-nosed figures counting their money. Most prominently, the image of Haman’s ten hanged children is mirrored with a depiction of twelve dead Nazis, presumably a reference to the Nuremberg tribunal and Julius Streicher’s declaration “Dies ist mein Purimfest 1946!” seconds before he was hanged. These moments of explicit connection between the past and the future are present throughout the book, and given that they also appear in Gorfinkel’s graphic novel Haggadah it is fair to understand them as a hallmark of the artist.

This is all to say that the book is good; just ask my daughter, who hasn’t yet learned to read and yet has told herself the story of Purim countless times this past week with the aid of its images. Even if this isn’t a book for kids, it is certainly a book that kids are going to like. This leads me to my chief criticism of the edition, which is that it highlights all the ways that Purim cannot be all the things we want it to be at the same time.

Take that image of the menorah, for example. When the Megillah is read aloud, the reader typically acknowledges the sadness behind the verse by momentarily dropping from Esther’s upbeat cantillation to the mournful tones of the book of Lamentations. This book by Gorfinkel and Nathan doesn’t really allow for that kind of complexity; its sad moments don’t feel all that sad. The same is true for the multiple hangings that take place throughout the book, which are depicted as literally bloodless; more often than not, the hanged figures only appear in silhouette. (By contrast, in an edition of the Megillah that my own publishing house released this year, some of the cards are literally speckled with “blood”—but we weren’t making something quite so focused on children.) Jewish violence against gentiles is depicted as a Hanukkah-style military contest—armed men pitted against armed men—whereas the story of Esther has the Jews at large, and not just soldiers, acting under a literal license to kill. I found myself particularly struggling with the illustrations in their depiction of how the king chose his new queen, a process that in the text of the Megillah was almost certainly not fully consensual, if it was consensual at all. In all of these instances, I found that the illustrators’ choices only amplified my bafflement at how a holiday with a story like this could be the most kid-centric.

I don’t think this is the illustrators’ fault. As with all Bible commentaries, sometimes the questions raised are more interesting than the answers given; in fact, great questions with unsatisfying answers are one of the primary engines for Torah study. The era of graphical commentaries is only just beginning; the Megillah itself will doubtless be illustrated over and over again, and each attempt will try to say something new.

It is my hope that future editions of the Megillah will attempt to grapple with the tensions unresolved by their predecessors, perhaps helping us solve visually what those of us stuck in the texts have struggled with for so long, using the nuance of imagery to communicate things that are too tricky for mere words, much as the rabbis used aggadah to say things that Halakhah could not. Children raised on books like this are going to look for something more as they grow. What will we give them next?

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.