Shmuel Lubin

Introduction

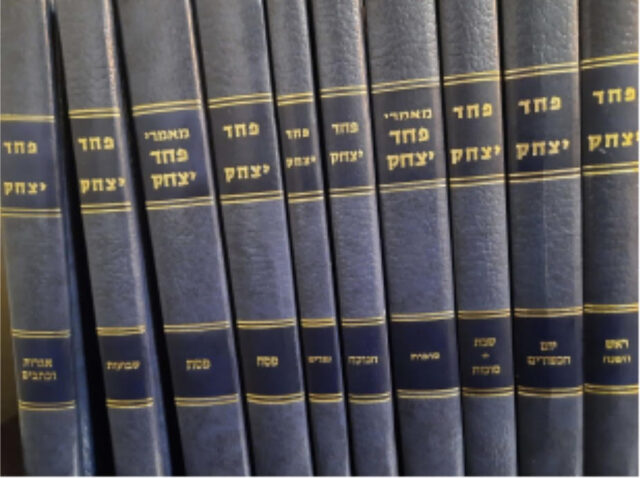

R. Yitzhak Hutner, former Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chaim Berlin, is widely recognized as one of the most original and penetrating thinkers to be associated with the modern Yeshiva world. To quote Dr. Yaakov Elman, his writings include “disquisitions on the difference between the psychologies of generalists versus specialists, the tensions of the individual within human society, other problems of identity and personality, of change and renewal, the problem of mortality and other aspects of the human condition, and much more.”[1] Instead of being organized around major topics of Jewish theology, however, his seminal work, the multi-volume Pachad Yitzhak, is centered on the Jewish holidays, as R. Hutner recognized the special power of these yearly landmarks to inspire him to share with his students matters of the mind and spirit.[2]

With an eye toward remaining faithful to R. Hutner’s holiday-centered works, this essay will explore an idea of R. Hutner’s as it pertains to the holiday of Pesach, but it is a topic that pervades his writings with some frequency: the meaning of suffering. Questions relating to “the problem of evil,” human suffering, failure, and destruction are often discussed by R. Hutner only in an oblique or abstract fashion, but nevertheless can be shown to be lurking in the background of some of his most well-known ideas. By examining R. Hutner’s understanding of this issue, particularly through the context of the Pesach seder, we may gain insight not only into his theological framework but also develop an appreciation for how the Pesach holiday itself can provide spiritual nourishment for confronting personal and national tragedies.

The Seder rituals and the text of the Haggadah are framed by the essential mitzvah of the night: sippur yetziat Mitzrayim, the biblical commandment to retell the story of our departure from Egypt. As with every mitzvah, the precise details of its fulfillment are dictated by multiple halakhot, but the definition of the mitzvah is relatively clear; on the first night of Pesach, there is a certain content that should be imparted to one’s children or audience: the narrative telling of how God redeemed our nation from the Egyptian bondage.

Additionally, however, the Torah legislates not only the content but also the manner in which this story is told. As stated in the Gemara (Bavli Pesachim 116a), the storyteller is supposed to provoke his children to ask questions that will elicit the telling of this story, and even someone sitting alone reciting the story in solitude must ask questions of himself/herself regarding what happened on this night.[3] This halakhah pertains to the manner of storytelling that a person must engage in, but there is also another detail regarding the story itself. The Mishnah (Pesachim 10:4) states that the story arc must follow a particular trajectory, “beginning with disgrace and ending with praise”—either the disgrace of slavery and the glory of redemption, or the disgrace of “our forefathers began as idolaters,” culminating with our present dedication to the true religion. The narrative must take the form of the nation’s Egyptian journey, which began in the darkness of exile and culminated in God’s glorious redemption.

Thus, R. Hutner points out that both in form and in content, the mitzvah of sippur yetziat Mitzrayim follows a pattern of developing from ignorance to knowledge, from difficulty to resolution. This set of requirements cries out for an explanation: why must our experience of the good necessarily be preceded by darkness? While he doesn’t explicitly categorize them as such, a careful reading of Pachad Yitzhak [subsequently: PY] on Pesach, Maamar 17, reveals – or, at least, hints – to three distinct but interconnected approaches to understanding why a discussion of Israel’s suffering must precede talk of its redemption. These approaches of R. Hutner to explaining the procedure of sippur yetziat Mitzrayim are not only relevant to the story of our long-ago national suffering in Egypt, but also pervade R. Hutner’s writing as part of his theological understanding of suffering more generally as functioning within the divine plan.

1. Suffering as Contrast: Appreciating Light from the Darkness

Basing himself on a section in the work of Maharal (Gevurot Hashem, Ch. 52), R. Hutner first explains this framework for telling over the Pesach story as reflecting a general principle regarding God’s providence. Maharal writes:

“The praise which is preceded by condemnation is a greater praise, just as the day is preceded by night,”[4] because “perfection is not to be found at the beginning of anything in this world… it is not appropriate in this world to have the light at its beginning.”

The emphasis that Maharal places on “this world” will be explored later, but R. Hutner understands that at the most basic level, this is a statement about the ability to appreciate ‘the light’ by contrasting it with darkness. Something perfect, Maharal teaches, can only be praised if there is an acknowledgment that it could have been imperfect. This corresponds to the cosmic order established at creation, where “evening preceded morning” (erev kodemet laboker) and “first there was darkness and then light” (me’ikara hashukha v’hadar nehora). Thus, Maharal explains that the structure of the seder narrative reflects a profound theological truth about how God’s blessing is manifest in the world: it can only be appreciated against the backdrop of a prior absence.

The perfect metaphor for this phenomenon is one that is in fact much more than a metaphor: it is the manner of teaching by question and answer. To quote R. Hutner:

“It is clear that for any idea which we have incorporated into our beings as a resolution of our doubts or as a solution to our questions, the ‘praise’ is much greater than what it would have been had this realization come about simply, without preceding doubts or problems. Anyone who is involved in intellectual matters knows that many times an answer is more in need of the question than the question is in need of an answer.”

A truth, a profound knowledge, can only be properly appreciated if it is an answer to a question, because the acknowledgement of the question makes the seeker aware of the need for a resolution; it creates a thirst for the knowledge, a hole that the missing puzzle piece must be fitted into. The method of question and answer is thus the perfect format for retelling the story of Pesach; it is the model for appreciating the light by way of darkness, for recognizing the “praise” of redemption by way of contrasting it with the disgrace of exile and idolatry. Just as the story itself must be told “from disgrace to praise,” it must be told in a manner consistent with that message, by way of question and answer.

I once heard a teacher of mine, who had learned in Yeshivat Chaim Berlin under R. Hutner for many years, share a story related to this aspect of R. Hutner’s educational philosophy: speaking to someone who was preparing for a role as a teacher of Torah, R. Hutner advised him to never provide answers to students “until their tongues were white with hunger” in desperation for hearing the answer. In other words, to properly appreciate the solution to a problem, you must first fully explore the nature of the problem. An even more illustrative demonstration was a story my teacher told about himself: in an early Gemara shiur of his, he began discussing a well-known question of Rabbi Akiva Eiger, saying, “Rabbi Akiva Eiger has a problem here,” and a student interjected, “So if he has a problem, let him deal with it!” The student’s attitude, if not his impetuousness, is appropriate: there is no value in hearing an answer to someone else’s question unless you are bothered by the same difficulty.

Applied to the theological question of suffering, this first approach would suggest that life’s difficulties serve as an educational contrast that allows for a deeper appreciation of subsequent joy and blessing. Just as someone who is experiencing pangs of starvation will be so much more thankful for getting food to eat, so too we cannot properly appreciate the value of God’s redemption without first appreciating how necessary it was, how awful the exile. It is this lack that must be discussed on Pesach night, and it is also the means through which the story is told; it must begin with questions, with “difficulties,” or kushiyot in Hebrew – a word that denotes both hardships and inquiries.

This principle—that appreciation requires contrast—is deeply rooted in Jewish tradition. Rashi, commenting on Bereshit 2:5 about why God had not yet sent rain upon the earth, explains: “What is the reason it had not rained? Because ‘there was no man to work the soil,’ [the text of verse in question], there was no one to recognize the goodness of rain. When man came and understood that they were necessary for the world, he prayed for them and they fell, causing trees and vegetation to grow.” The Maharal of Prague elaborates on Rashi’s explanation by referencing a teaching of the sages: “It is forbidden to do good to a person who does not recognize the good, and therefore as long as man did not exist—it did not rain.” According to this view, the very capacity to recognize and appreciate a blessing is a prerequisite for its bestowal; God created Adam hungry and lacking food so that he would know to thank God when it arrived.

Rav Hutner’s application of this concept to the Pesach Seder is not so distant from that of Rambam in his Guide for the Perplexed (3:43), who explains why the celebration of Pesach includes the consumption of bitter herbs along with the sacrificial meat: “It consists in man’s always remembering the days of stress in the days of prosperity, so that his gratitude to God should become great and so that he should achieve humility and submission.” He applies the same principle to the festival of Sukkot, where dwelling in temporary booths reminds us of our previous state of deprivation before entering “richly ornamented houses in the best and most fertile place on earth, thanks to the benefaction of God,” which we can appreciate by recognizing its contrast. By experiencing the “disgrace” of our past, we become capable of truly valuing the “praise” of our redemption.

2. Suffering as Creative Destruction: Breaking Down to “Build Back Better”

It is hard to imagine that human suffering exists only as an appreciation tool, and R. Hutner indeed provides another approach even in the same passage explored above, PY: Pesach 17 (although, as mentioned above, he does not explicitly distinguish between them). This second approach views suffering not merely as a means for contrast to heighten subsequent appreciation, but as a necessary precondition for creating something greater. According to this understanding, the disgrace with which we begin the story of the Egyptian exile is not simply the dark backdrop against which redemption shines more brightly, but the suffering is itself the device through which redemption could sprout. Much like a construction crew must first demolish an existing structure to make room for a more expansive and magnificent building, certain forms of suffering serve as a catalyst for rebuilding something greater than what existed before.

To explain this in the context of sippur yetziat Mitzrayim, R. Hutner once again looks to a passage from Marahal, this time describing the very beginnings of the exile. The verses in the Torah which introduce the book of Shemot begin with the deaths of Yosef, his brothers, “and that entire generation” (Shemot 1:6). R. Hutner explains that the demise of Yaakov’s sons was necessary for the nation to move forward; only through their deaths could the Jewish people start proliferating at miraculous rates. Here too, R. Hutner references Maharal, who explains (Gevurot Hashem Ch. 12) that because Yaakov’s descendants at the start of the Egyptian exile numbered seventy, a number signifying perfection, they could not have begun multiplying as rapidly as they did to reach the symbolic national number of 600,000 men without first ‘breaking’ the prior perfect number of seventy: a prime example of destruction for the sake of construction.

This insight reveals a profound pattern in divine providence: sometimes, what appears to be a setback is actually necessary for progress toward a greater state of being. This principle applies not only to national history but to individual spiritual growth as well. In a well-known letter to a discouraged student (Iggerot Pachad Yitzhak, #128), R. Hutner challenges the common misperception that great Torah scholars achieved their stature without struggle:

“We have a terrible disease among us. When we discuss the greatness of our Torah giants, we deal with the final summary of their greatness. We speak of their perfection as if they emerged fully formed from the Creator’s hand… The wise know well that the intent of the verse ‘seven times the righteous will fall and rise’ (Mishlei 24:16) is not that despite falling seven times, the righteous person rises. Rather, the very essence of the rising of the righteous is through the seven falls.”

R. Hutner rejects the hagiographical portrayal of “gedolim” (prominent Torah giants) as having been born perfect. Instead, he insists that their greatness came precisely through their struggles and setbacks which provided the catalyst for building something greater.

This dynamic of “creative destruction” appears elsewhere in R. Hutner’s writings as well. In several places throughout his works, R. Hutner references the concept of “bittulah zehu kiyyumah,” the idea that the nullification of Torah is its fulfillment, highlighting instances when an apparent act of ‘nullification,’ of destruction, allows for the flourishing of something greater.[5] This phrase appears in a Talmudic discussion (Menachot 99a-b)[6] concerning the episode of Moshe breaking the tablets, to emphasize the fact that this very literal “destruction of Torah,” the smashing of the engraved words of God, ended up re-establishing the Torah. R. Hutner elaborates on this concept in his discourse on Chanukkah (PY: Chanukkah 3), where he develops the profound and counter-intuitive idea that Torah can actually be increased through its loss:

“The Sages said that had the tablets not been broken, Torah would never have been forgotten from Israel (Eruvin 54a). Thus, we find that the breaking of the tablets also caused the forgetting of Torah. From here we learn a wonderful innovation [hiddush nifla]—that it’s possible for Torah to increase through the forgetting of Torah, to such an extent that one might receive commendation for causing Torah to be forgotten… Behold, the Sages said that three hundred laws were forgotten during the mourning period for Moses, and Otniel ben Kenaz restored them through his dialectical reasoning [pilpul]. These words of Torah, of dialectical reasoning to restore the laws, are precisely the words of Torah that increased only through the forgetting of Torah… All the differences of opinion and competing approaches are expansions and glorifications of Torah that are born specifically through the power of Torah’s being forgotten.”[7]

Just as the Egyptian exile created the conditions necessary for national growth from seventy to six hundred thousand, the destruction of the Torah through forgetting its laws creates space for the intellectual creativity of the rabbis to expand the Torah.[8]

3. Suffering as Purification: A Prerequisite to Godliness in an Imperfect World

In these first two approaches’ discussions as to how to understand human suffering, we have yet to contend with what Scripture itself seems to emphasize most frequently: suffering as divine punishment, inflicted by God as retribution for the sins either of an individual or for the nation as a whole. While R. Hutner does not deny that God inflicts suffering upon people as punishment, he also hints to a related but distinct concept: especially when it comes to the national destiny of the Jewish people, suffering is a necessary component of receiving divine goodness at a mystical-metaphysical level.

Returning to our central text in Pesach #17, R. Hutner cites a mystical secret in Ramban’s commentary to a puzzling verse in Vayikra (26:11), which includes among God’s blessings that He will bestow upon Israel when it is perfectly righteous a promise that, “I will place My dwelling among you, and My soul shall not reject [ga’al] you.” At first glance, it seems rather strange to think that God would ‘dwell among you’ but nevertheless still ‘reject you,’ and so Ramban translates this word ga’al according to a secret of the Torah:

I do not know what the reason is for this, that the Holy One, blessed be He, would say that if we keep all the commandments and do His will, He will not reject us… But this matter is a secret of the secrets of Torah: [God] says that He will place His dwelling within us and the spirit from which the dwelling comes will not purge [ge’al] us, like a utensil that is purged in boiling water. Rather at all times your clothes will be white and new.

The promise that at some future time, God’s “dwelling among the people” would not involve “purging” implies that, during other periods of Jewish history, God’s presence (Shekhinah) among His people does indeed necessitate a process analogous to the purging of vessels through boiling water. R. Hutner’s citation of this Ramban in the context of sippur yetziat Mitzrayim indicates that the Egyptian exile and bondage was part of this purification process. This is the “disgrace” with which the Seder narrative begins, with the story of great national tragedy that was necessary not only because it helped us appreciate God’s salvation, and provided the opportunity for growth on a psycho-spiritual level, but was also necessary on another level which Ramban associated with esoteric teachings, a secret of the Torah.

Elsewhere, R. Hutner clearly differentiates between a “psychological” explanation for suffering’s purifying power and a mystical-metaphysical one. As a matter of historical interest, it is worth mentioning that this discourse was elaborated upon by R. Hutner during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur of 1970, mere days after his own harrowing experience as a hostage when Palestinian terrorists hijacked TWA Flight 741 as he was returning from Israel to New York.[9] In one of these pieces, Pachad Yitzchak on Yom Kippur (#12), R. Hutner addresses the question of how suffering can effect atonement even without repentance. He first cites a psychological explanation from Rabbi Avraham Grodzinsky, one that is characteristic of the Mussar theology of Slobodka where he taught: even without improving a person’s character traits, the experience of physical suffering causes a person to identify less with their material bodily needs. Although he respects this approach, saying that these words are “worthy of he who had expressed them” (a reference to Rabbi Avraham Grodzinsky’s own sterling character as well as his terrible fate at the hands of the Nazis), Rav Hutner finds it insufficient.

Instead, Rav Hutner develops a metaphysical approach: he proposes that suffering inherently depletes the cosmic forces of evil in the world, because the force of evil is at the root of human suffering while simultaneously being the same force that drives people to sin, thereby creating barriers to divine revelation. He even goes on to use this idea to explain the logic behind the Jewish conception of Hell, for “it is the same law that applies equally in both the world of bodies and the world of souls,” where the suffering of the soul, even in a realm where no repentance or self-improvement is possible, is still going to act as a purification device allowing for the soul to subsequently be entered into the domain of God’s glory.

It is this more mystical explanation for suffering that Rav Hutner sees as being particularly relevant to the national history of the Jewish people. The historical experience of the Jewish people has been filled with suffering; in one instance, Rav Hutner makes special note of the fact that a potential convert to Judaism must acknowledge that joining the Jewish people in exile is ‘a bitterer gesheft,’ a bitter endeavor (Maamarei Pahad Yitzhak: Pesach 46:7). Our forefather Jacob was not called “Israel,” the true spiritual progenitor of the nation that would bear his name, until engaging in a wrestling match that left him injured (PY: Chanukkah 2). Both of these points are used by Rav Hutner to demonstrate that the exile, and the suffering that comes along with it, constitute the very essence of Jewish identity: they are part-and-parcel of Israel’s divinely ordained purpose.[10]

In PY: Pesach 46-48, R. Hutner distinguishes between two modes of global divine providence, of how God provides goodness to the world in general: chesed vitur (grace through concession) and chesed mishpat (grace through justice, or ‘justified’ grace),[11] and writes that this transition occurred between the moment of the Exodus from Egypt and the revelation at Mount Sinai fifty days later.

Under a regime of chesed mishpat, divine blessing is calibrated to the worthiness of its recipients. In an earlier elaboration of this concept (PY: Rosh Hashanah #4), R. Hutner connects this with the concept of “ge’on Ya’akov,” the pride of Jacob, by saying that only the descendents of Jacob are able to withstand such restrictions on divine beneficence:

God’s governance by the standard of dealing stringently “like a hair’s breadth,” that applies uniquely to the Jewish people viewed as “Your people are entirely righteous,” and therein appears the pride of Jacob, for through its service of God it brings into existence the world [of strict Din] that was unable to endure in the order of creation.

The implications of this theological framework for understanding Jewish suffering, perhaps especially if applied to Israel’s first national experience of suffering under Pharaoh and the Egyptian taskmasters, closely parallels Ramban’s esoteric teaching about God’s “purging” of Israel. In both discussions, R. Hutner refers to “imperfections,” perhaps not sins worthy of harsh punishment in the conventional sense, but barriers to divine goodness nonetheless. Just as vessels require purification through boiling water to remove their impurities, the Jewish people require purification through suffering to become worthy vessels for divine presence under the system of chesed mishpat until they have been completely perfected. Once that process is complete, at the end of days, “your clothes will always be white,” as Ramban had quoted, indicating a metaphorical state of purity when no more suffering will be necessary, which will come only once history has reached its ultimate denouement.

Rav Hutner’s Applied Theodicy

R. Hutner applied this way of thinking to both national and individual experiences,[12] but the concept of suffering as purification for the Jewish people takes on special significance when considered in relation to the greatest tragedy of modern Jewish history—the Holocaust. In 1977, The Jewish Observer published a translated discourse by R. Hutner entitled “‘Holocaust’: A Study of the Term and the Epoch It’s Meant to Describe,” which was described by the editors of the paper as articulating a “Daas Torah perspective” on the Holocaust. The article aroused a good deal of controversy for (among other things), R. Hutner’s peculiar interpretation of historical events, his opposition to the use of the term “Shoah” or “Holocaust,” and his strident anti-Zionism.

What had been somewhat lost in the shuffle, however, at least at the time, is the extent to which R. Hutner’s ideas as expressed in this article cohere with his thought more generally.[13] In the concluding passage of the Observer article, Rav Hutner states:

It should be needless to say at this point that since the Churban [destruction] of European Jewry was a tochacha phenomenon, an enactment of the admonishment and rebuke which Klal Yisroel carries upon its shoulders as an integral part of being the Am Hanivchar — G-d’s chosen ones — we have no right to interpret these events as any kind of specific punishment for specific sins. The tochacha is a built-in aspect of the character of Klal Yisroel until Moshiach comes and is visited upon Klal Yisroel at the Creator’s will and for reasons known and comprehensible only to Him.

This idea is remarkably consistent with what we have seen, especially regarding the third, more mystical, approach towards the meaning of suffering in R. Hutner’s thought. Just as his discussion of the Egyptian bondage in Pachad Yitzchak on Pesach presents suffering not as punishment for specific transgressions but as a necessary purification process for the nation, his treatment of the Holocaust follows the same pattern. The reference to “tochacha” (divine admonishment) as “a built-in aspect of the character of Klal Yisroel” parallels his conception of suffering as an inherent part of Israel’s special relationship with God under the system of chesed mishpat.

R. Hutner’s approach towards the value of suffering can be understood according to any of the three models referenced in PY: Pesach #17, but seems to accord best with his view of suffering as an integral part of Jewish chosenness. As it appears throughout his writings, this view points towards R. Hutner’s response to the problem of evil; he proposes not a philosophical solution but what we might call an eschatological one. For R. Hutner, all suffering is purposeful, but its meaning will not be fully understood until the end of days. A foundation for this perspective is cited by R. Hutner here in PY: Pesach #17 in the name of Rabbeinu Yonah:

One who trusts in God must accept in the depths of his being that the darkness will be the reason for the light (she-yiheh ha-hoshekh sibat ha-orah), as it says (Micha 7:8) ‘for I have fallen and will arise; though I sit in darkness God is my light,’ and the Sages have said, ‘if I would not have fallen, I would not have arisen; had I not sat in the darkness I would not have had light.’

This passage reveals that for someone who believes that God is both good and in control of the fates of humanity, it must be the case that those fates are aimed at ultimately bringing goodness. In the parable of the sages, darkness is not merely a prelude to light or even a useful contrast that makes light more appreciable—it is actually the cause of light, the condition that makes illumination possible. The relationship between suffering and redemption is a causative one.

Salvation that came by means of difficulty, redemption through exile, is precisely the salvation that is celebrated on the holiday of Pesach – and indeed, according to R. Hutner, is at the heart of nearly all the holidays.[14] Sukkot commemorates not the original clouds of glory that accompanied the Israelites upon leaving Egypt, but the clouds which were returned to them after they had sinned with the Golden Calf and subsequently repented (PY: Sukkot 19); R. Hutner notes regarding Shavuot that it celebrates a holiday of broken tablets, and the act of smashing the tablets was only later revealed to be a positive development (PY: Shavuot 18:17), Purim represents the ability to recognize God even when He is hiding His face in exile and operating through natural means (PY: Purim 34), and so on.

Most importantly, however, it is this form of salvation through difficulty that will be celebrated at the end of days, in the Messianic Era. The question posed by the problem of evil will be resolved at the end of days, not through philosophical argumentation but through a transformation in the fundamental nature of reality that will retroactively reveal how all of history’s suffering was an expression of divine love preparing us for an unimaginable good.[15] In Maamarei PY: Sukkot 31, R. Hutner identifies the primary difference between this world and the World to Come as being precisely in the realm of theodicy: “The fundamental difference between the conduct of this world and the conduct of the Garden of Eden is that in this world the path of the righteous is bad for him and the wicked is good for him. But in the Garden of Eden, the clear conduct of the righteous is good for him and the wicked is bad for him.”

Recognizing this truth in an unredeemed world is not fully possible. R. Hutner frequently cites the Gemara (Berachot 48b) teaching that “This world is not like the World to Come. In this world, on good tidings one says ‘Blessed is He who is good and does good’ and on bad tidings one says ‘Blessed is the true Judge.’ But in the World to Come, all will ‘be good and do good’… Only ‘on that day, the Lord will be One and His name One’.”

Yet, the Jew is called to cover his or her eyes, to ignore the apparent reality of evil and nevertheless declare that God is One, orchestrating events so as to move history towards a glorious ending. As R. Hutner explains in PY: Pesach 60, the recitation of the Shema prayer requires closing one’s eyes because complete acceptance of divine sovereignty necessitates “cleansing the heart from all kinds of complaints against the conduct of Providence.” This cleansing comes through recognition that “there is nothing here but the Good and the Beneficent,” even when current experience suggests otherwise.

On Pesach, we can recount the narrative of our time in Egypt with joy only because we know how the story ends. Yet we must not neglect to begin at the beginning, with the terrors of slavery, to demonstrate that we could not have achieved the great heights of redemption without first experiencing profound suffering.The experience of the Pesach Seder can thus be so uplifting precisely because it begins with the disgrace of bondage and the difficulties of questions. In this pattern lies the challenge of willfully blinding ourselves to the reality of suffering, to the deepest and most difficult question of faith in exile, but it can also serve as a profound comfort—the assurance that just as the Egyptian bondage was necessary for redemption, so too will history’s sufferings ultimately be revealed to be catalysts for salvation, when “at evening time there shall be light.” (Zechariah 14:7). Experience of the Pesach Seder even in the darkest times, when God’s providence is in question, serves to instill within us the faith that our current exile and suffering—all the bloodshed and all of the tears—are somehow, in a presently unfathomable way, moving us toward a brilliant future.

[1] Yaakov Elman, “Pahad Yitzhak: A Joyful Song of Affirmation,” Hakirah 20 (Winter 2015). For major explorations of his thought, see the works quoted in Yaakov Elman, “Rav Isaac Hutner’s Pahad Yitzhak: A Torah Map of the Human Mind and Psyche in Changing Times,” in Stuart Halpern, ed., Books of the People: Revisiting Classic Works of Jewish Thought (Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2017), and more recently the dissertation written by Alon Shalev, to be adopted by Brill as Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner’s Theology of Meaning (forthcoming).

[2] R. Hutner believed that ideas pertaining to the essence of Torah life must be transmitted in the context of celebrating that Torah life especially over the holidays. In PY: Iggerot #12, R. Hutner describes how “receiving the teacher’s presence during festivals” enables students to understand the teacher’s perspective and live by his example, rather than merely receiving specific teachings. Cf. PY: Iggerot #91, where he refuses to forgive a student who neglected to spend the High Holidays in the yeshiva environment, and PY: Pesach 51:4, noting the “special nobility” of structuring one’s service of God around festivals.

[3] R. Hutner (PY: Pesach 5) observes that this requirement may also be hinted at in the verses from Tehillim (114:6), used for Hallel, which describe the Egyptian Exodus with questions: “what is with you, O sea, that you flee?”

[4] On “day following night” in R. Hutner’s thought as it relates to the theme of this essay, see PY: Shabbat 13

[5] PY: Shavuot 5, 13:3-6, 18:15-19, 40:6, PY: Chanukah 3, 8

[6] The original phraseology of the Gemara according to the standard Vilna edition and all available manuscripts is bittulah shel Torah zehu yesodah, “nullifying Torah is its establishment,” but R. Hutner preferred the version of this phrase as it appears in Sefer Hassidim #952.

[7] R. Hutner’s paradoxical celebration of the loss of Torah knowledge precipitated by Moshe’s smashing the tablets was anticipated by R. Yosef Dov Halevi in She’elot u-Teshuvot Beit Halevi: Derashot, Derush #18. Cf. Introduction of R. Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin to Ha’amek She’eilah and the Introduction of R. Shimon Shkop to Sha’arei Yosher

[8] Another application of this idea can be found in R. Hutner’s explanation of the psychological re-creation necessary for the process of repentance. See PY: Rosh Hashanah #29 among other places.

[9] Reuvain Roth (ed), Reshimot Lev: Rosh Hashanah ve-Yom ha-Kippurim, Brooklyn, 2000. See headings for discourses given in the year 5731.

[10] In various forms, the idea that national suffering and especially Israel’s exile is beneficial on some cosmic level is pervasive in Jewish thought, beginning with Yeshayahu chapters 52-53 (see rabbinic commentaries ad. loc.). For some earlier examples, see Kuzari 1:113-115, Radak to Yirmiyahu 11:4 regarding the Egyptian exile, and R. Ovadiah Seforno to Bereshit 28:14 (based on Bereshit Rabbah 69:5, and echoed by Kli Yakar and Ha’amek Davar there). Sources that were likely direct influences on R. Hutner’s thinking include Maharal, Netzah Yisrael Ch. 15-16 and Ch. 35; R. Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, Derech Hashem 2:3 & Da’at Tevunot #54 and #146; R. Zadok ha-Kohen of Lublin, Resisei Laylah #17, Pri Tzaddik to Parashat Va-Ethanan, Dover Tzedek, Likkutim 4:77 (a likely source for Rav Hutner’s PY: Purim 34 discussed below); R. Yehuda Leib Alter of Gur, Sefat Emet, Pesach 5631; perhaps also traditional commentaries on Gemara including R. Ezekiel Landau, Tzelach to Pesachim 50a and 56a, R. Yaakov Ettlinger, Arukh La-Ner Sanhedrin 96b. On how Maharal and R. Moshe Chaim Luzzatto influenced R. Hutner, see Shalev’s dissertation p. 112-152 (although Shalev does not cite R. Hutner’s explicit praise of Luzzatto in Maamarei PY: Sukkot 99:8). For R. Zadok ha-Kohen’s and R. Alter’s influence, see Elman, “Rav Isaac Hutner’s “Pahad Yitzhak”.”

[11] In a somewhat unusual (but not unique) fashion, R. Hutner’s reference to this idea has a recursively self-referential quality to it: in both Pachad Yitzhak: Pesach #46 and #48, R. Hutner quotes himself from Pachad Yitzhak: Shavu’ot 8:4, which itself is a quote from Pachad Yitzhak: Rosh Hashanah #4!

[12] On the connection between the two, see Maamarei PY: Sukkot 52:10. In a letter to a student experiencing life’s travails, R. Hutner ‘praises’ him for experiencing hardship as an inspiration towards repentance (Iggerot PY: #106, see also #253). Regarding national suffering, aside from his article on the Holocaust, see Maamarei PY: Sukkot 107 which the editors note was “likely” delivered during the Yom Kippur War.

[13] See Lawrence J. Kaplan, “Rabbi Isaac Hutner’s ‘Daat Torah Perspective’ on the Holocaust: A Critical Analysis” (Tradition 18(3), Fall 1980). Kaplan challenges various aspects of the article, and reads R. Hutner as implicitly blaming the Holocaust on the “sin” of Zionism. However, Kaplan’s interpretation stems from a somewhat selective reading which mostly dismisses the article’s concluding paragraph reproduced above. In a later article, “A Righteous Judgment on a Righteous People: Rav Yitzhak Hutner’s Implicit Theology of the Holocaust” (Hakirah 10, 2010), Kaplan is thus forced to posit a contrast between “that essay’s explicit, more public and polemical, and, ultimately, rather conventional theology regarding the Holocaust” and “Rav Hutner’s implicit, more private and non-polemical theology on the subject” (103). See Gamliel Shmalo, “Radikaliut Philosophit B’Olam HaYeshivot” [Philosophical Radicalism in the Yeshiva World]. Hakirah 19 (2015) for a more coherent interpretation of the Observer article and its context within Haredi thinking on the Holocaust.

[14] See Maamarei PY: Pesach 16:18-19, where R. Hutner states explicitly that the unifying feature of the three pilgrimage festivals is precisely this point (elaborated upon, with respect to Pesach only, in PY: Pesach 15). In PY: Yom Ha-Kippurim 21, R. Hutner adds to this concept that the celebration of the holidays is also meant to prefigure the celebration of God’s actions at the end of days. See also PY: Pesach 54, reproduced also as PY: Shabbat 2

[15] This idea appears in too many of R. Hutner’s writings to cite, but see especially PY: Rosh Hashanah 11, PY: Pesach 60, and PY: Purim 10

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.