Jeffrey Saks

Homer. Milton. Joyce. Borges. Blindness, it seems, does not dim the literary vision of great poets and authors.

Hebrew poet Erez Biton is one such person. Born to Moroccan-Jewish parents in Algeria in 1941, he fled with his family in 1948, heading to the fledgling Jewish State. After a period of time in an absorption center the family settled in Lod where, at age eleven, Biton lost his eyesight when he was wounded by a stray hand grenade that detonated in a field where he was playing. Following this trauma he was sent off to the dormitories of the Jerusalem School for the Blind, after which he completed university degrees in social work and rehabilitative psychology, fields to which he dedicated the first fifteen years of his professional life. Afterward he transitioned to journalism, working as a columnist for the Ma’ariv newspaper, before accepting the mantle of poetry as his main vocation.

In the history of culture, memorization begins with poetry. We, so attuned to the power of Oral Tradition, might take note of the fact that blind Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey were not committed to writing for numerous centuries. I recently had an opportunity to spend Shabbat with Biton at a weekend gathering organized by Jerusalem’s Agnon House. During one session he discussed his work and recited, from memory, a selection of his poems. I sensed that he was playing with turns of phrase in the lines of poetry, finessing the verses as they were spoken, despite some of them having been first composed decades earlier. It occurred to me that I was witness to literature which still bore an air of orality.

Later, when I asked him if he thinks of his work as more of an oral or written artifact, he confessed that no one had ever asked him about this but, despite his poems having been cast black on white and bound in books, he feels less restricted by this than he imagines a sighted poet might feel. For him the poem remains principally a spoken text—print being a medium that, as a blind man, he feels less bound by. This allows him to continue tinkering with poems “composed” years ago. (He was delighted to hear that Agnon, too, was an inveterate reviser and polisher of his works.)

Already with his first volume of poetry, Minhah Marokait (Moroccan Gift, 1976), he established himself as a significant voice on the Israeli literary scene. Most often Biton is described as the founding father of Mizrahi poetry in Israel (that is, the community of immigrants from the Sephardic lands and their descendants). Biton’s achievement within that ethnic community has been compared, no less, to that of national poet H.N. Bialik in his own era. There can be no doubt that his fame, linked as it is to his Mizrahi heritage, is due in no small measure to the powerful expression his poetry gives to the often traumatic experience of the Mizrahi immigrants to early-State Israel.

By the late 1970s, the cultural scene was just beginning to show openness to forms of expression that lay outside of the Ashkenazi hegemony. Biton’s poetry was taken note of, independent of the compelling biography of its composer, for its powerful depiction of the often marginalized and displaced experience of those immigrants. It also gave voice to their struggle to find themselves as individuals and as a community within the confusing cultural politics of an increasingly multicultural Israel.

[Listen to the musical adaptation of his poem “A Moroccan Wedding.”]

In recognition of his literary gifts, and his six volumes of published poetry, Biton has been decorated with Israel’s most prestigious literary laurels, including the Amichai and Bialik Prizes (both in 2014) and the Israel Prize (2015). Unfortunately, only one volume appears in English (anthologizing a sampling of his work), published as You Who Cross My Path (Boa Editions, 2015), with skillful translations by Tsipi Keller.

However, the focus on Biton as a distinctly ethnic poet distracts readers from some other very compelling aspects of his art. In his two most recent volumes, Nofim Havushei Einayim (Blindfolded Landscapes, 2013) and Beit ha-Psantarim (The House of Pianos, 2015), he focuses on his life in the dark—having downplayed his blindness in earlier works. His move to the Jerusalem School for the Blind, which marked his transition from sight to darkness, constitutes another form of displacement—one which resonates with the earlier poems he penned about the geographic relocation of his immigrant youth. One poem, “Blindfolded Horses,” which opens his 2013 collection, reads:

In every blind person

a galloping horse abides

aspiring to tear across

distances.

Contrast this with a variety of his other poems which describe precisely how the sightless life is one of being reined in, almost corralled.

Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, when confronted with the blindness which beset his father, first considered the Biblical models of “blind Yitzhak and dim-sighted Yaakov,” as well as their Talmudic era descendants, Rav Yosef and Rav Sheshet. Frustrated that the response to their plight can only be conjectured, for the holy writings never communicate the experience of blindness suffered by these heroes of the spirit, Rav Lichtenstein found solace and insight in Milton’s sonnet “On His Blindness” with its magnificent conclusion, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” Its spiritual value to us as readers is great,

“[a]ll the more so, when that experience has been communicated through culture at its finest, by great souls capable of feeling deeply and expressing feeling powerfully. The tragedy of personal affliction, in particular, is thus more acutely perceived because the tragedy of a great soul—Milton in the throes of blindness, Beethoven on the threshold of deafness—as well as its passionate response bears the imprint of that greatness and imparts to us a keener sense of the nature of the experience.”

Biton is one such “great soul,” and through his poetry we sighted readers see more clearly. One theme which repeats throughout his work is how the blind use touch to compensate for the loss of vision; hands become ancillaries of both sight and language (recall “The Miracle Worker”). But here Biton is again at a disadvantage: The explosion that robbed him of his eyes also claimed his left hand, and badly scarred his right. In a cycle of poems in The House of Pianos, he introduces us to many remarkable souls who populated the School for the Blind. In one we encounter “Shlomo the Typing Instructor”:

You,

who prepared me for the typewriter keys

which would mediate between the world and me

to pass messages of love and beauty…

For a blind youth with literary aspirations, the braille-keyed typewriter is the best, perhaps only, form of writing available, and it must be mastered. But how does Shlomo instruct the boy who has been robbed not just of sight but also of the use of at least one of his hands which must need fly across those keys?

Place your hand

your only hand

in the middle, in the middle,

middle finger on letter Alef

index finger on Heh, Bet, Heh [spelling Ahava; love] …

Craft

messages, messages,

to that which is outside of yourself

to give yourself through the keys

to give your soul through the keys.

To peck out letters on a typewriter is one thing; to create music on the keys of a piano are something else entirely. In “For Mrs. Mira the Piano Teacher,” a tender-hearted woman sees the “gloomy heart of the child” whose physical defects prevent him from participating in her lessons while

“other children enter and exit your classroom

arriving with you

to the enchanted depths

of Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique.”

The boy knows he has no hope of learning to play, yet the music teacher, through a gentle touch, guides the “deformed five fingers of his only hand onto the piano keyboard”:

I did not play Schubert’s Trout Quintet

but from that kindness

there remains in me the magical journey

to distant mountains

and flowing streams.

One-armed pianists reminds us of Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, composed for a pianist who had lost his right arm in World War I. The concerto is remarkable in the virtuosity it reveals while compensating for and obscuring the disability from which it sprung. But isn’t all great art, and life itself, like this to one degree or another? Aren’t we all covering up our shortcomings by foregrounding our greater talents?

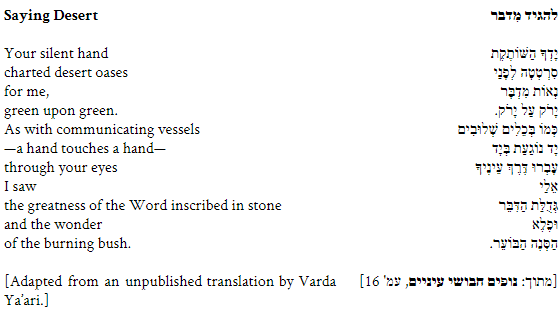

This brings to mind my personal favorite Biton poem. A number of years ago Biton was riding in a taxi from Arad to Jerusalem through the Judean Desert with Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), who is considered Israel’s greatest modern poet. Amichai had been among the first to recognize Biton’s promise, and was an early booster helping to bring him to prominence. As the car journeyed on Biton asked Amichai to describe the desert sights unfurling past them through the car windows. Instead of marshaling his powerful verbal skills, Amichai held Biton’s one hand for a long, silent pause, after which Biton replied, “Now I understand.” Later, he set the experience to verse in a poem dedicated to Amichai:

Later in history the desert becomes the locus of the near sound of silent communication via the kol demamah dakkah’s still, small voice. Indeed, the beginning of God’s revelation to Moses is not verbal, but visual, in the form of the “marvelous sight,” as the soon-to-be prophet describes the burning bush. But in the desert, God’s Word comes to us in a synesthesian symphony of “ro’im et ha-kolot,” in which voice and word are not only heard but seen. Perhaps this is the type of “vision” of which the Divine Poet, and those so graced in miniature here below—even if they be blind—are capable.Those attuned to the Biblical resonances in the poem, and to the symbolism of the desert and the Jewish experiences which unfolded there, will be sensitive to what is written here and what is hinted at between the lines. The “dibber,” Word [inscribed on stone], is God’s desert communication to His people, the force of which comes from what is missing. Unlike ink on parchment, the Two Tablets communicate through letters formed by absence: the stone chiseled away and removed from the rock becomes the communicating vessel.

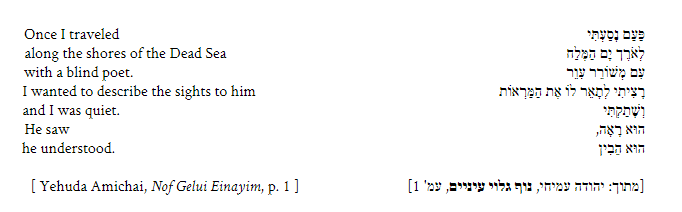

Biton’s poetry is a “concerto for one hand,” but unbeknownst to him on that car ride, he was playing a duet. In 2014, upon being awarded the Amichai Prize for Hebrew Poetry, he related the story of his desert trek with the late poet. Amichai’s widow, Chana, surprised Biton by revealing that Amichai, too, had written a poem based on that shared experience (not published in his collected works, but in a lesser known volume, it was unknown to Biton):

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about these paired poems, and the voice they give to the parallel experiences the poets shared in the taxi, is the volumes in which they appear. The blind poet Erez Biton published his poem about this experience in a volume entitled Nofim Havushei Einayim (Blindfolded Landscapes); keen-sighted Amichai included his in a work entitled Nof Gelui Einayim (Open-Eyed Landscape). Each man penned and titled these works unaware of the formulations of his friend and fellow poet! Amichai had held Biton’s hand and became an open braille book; the communication of the visual not through word but through silent touch, to transmit complementary experience, which then redounded to eerily coincidental artistic impulses of each poet working in isolation.

What was written by Oscar Wilde of Homer might one day be said of Erez Biton:

“I have sometimes thought that the story of Homer’s blindness might be really an artistic myth created in critical days, and serving to remind us not merely that the great poet is always a seer, seeing less with the eyes of the body than he does with the eyes of the soul, but he is a true singer also, building his song out of music, repeating each line over and over again till he has caught the secret of its melody, chanting in darkness the words that are winged with light.”

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.