Bezalel Naor

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the appearance of the classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a collaborative work by science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke and filmmaker Stanley Kubrick. The film traces the evolution of mankind “from ape to angel,” starting with prehistoric hominids and ending with the Star Child, with much attention lavished on the intervening species we call Homo sapiens. The development of man is carefully monitored from outer space by vastly superior unseen aliens who from eon to eon accelerate the process of evolution through the intervention of a mysterious monolith. Indeed, the iconic black monolith is the motif that remains with most viewers of this cinematic wonder.

To this day, interpreters are divided as to whether Space Odyssey is optimistic or pessimistic in outlook. According to the latest filmography by Michael Benson, Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018), the two collaborators brought to the project diametrically opposed perspectives. Kubrick, hot on the heels of his 1964 satire, Dr. Strangelove (a noir comedy concerning the nuclear arms race), had a rather dark vision of humanity. Clarke, on the other hand, was the eternal optimist. In Benson’s words: “It was an idea both could get behind, Clarke with his innate optimism about human possibilities, and Kubrick with his deeply ingrained skepticism” (p. 3). The unlikely alliance between a Jewish boy from the Bronx and an English gentleman (later knighted by Queen Elizabeth II as Sir Arthur C. Clarke) “was the most consequential collaboration in either of their lives” (p. 13). The savage brutality of prehistoric man on the African savanna may be credited to Kubrick; the beatific, almost messianic, image of the Star Child at the film’s conclusion was Clarke’s contribution. As Benson put it, “The single most optimistic vision in [Kubrick’s] entire body of work—2001’s Star Child—was Clarke’s idea” (ibid.).

*

By all accounts, Abraham Isaac ha-Kohen Kook (1865-1935) was a child of the cosmos. This is apparent to any student of his works. His famous pensée, Shir Meruba or Fourfold Song (the title was provided by his disciple the Nazirite), bespeaks the evolution of human consciousness in ever-widening circles from individualism to nationalism to humanism to a loving embrace of the universe as a whole. The pensée ends on this note:

The Song of the Soul,

the Song of the Nation,

the Song of Man,

and the Song of the World –

all combine…

(Orot ha-Kodesh, ed. Rabbi David Cohen, vol. 2, p. 445)

What is less known is that as a young man, Rav Kook actually composed a poem (in free verse), “Sihat Malakhei ha-Sharet” (The Conversation of the Angels), which, well before Kubrick, traces the trajectory of man from earthbound existence to future space travel. In 1968, when Space Odyssey took the “silver screen” by storm, travel beyond the earth’s atmosphere was already a reality. NASA’s Apollo program was well underway and, just a year later, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin would be the first men to walk on the surface of the moon. But when Rav Kook composed his poem, space travel was truly visionary.

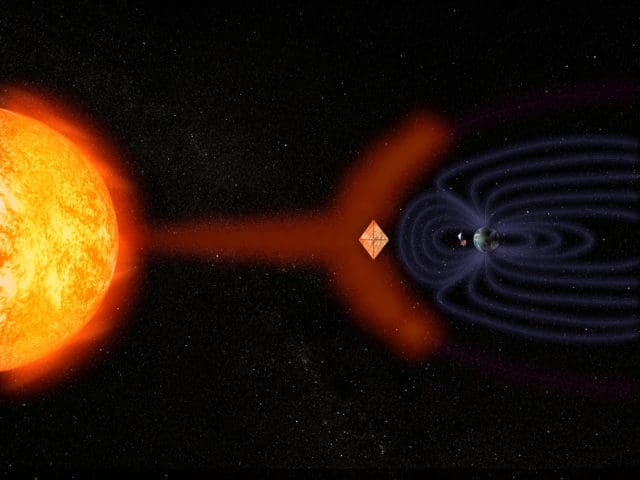

The recurring image of Rav Kook’s overview of human history—written from the perspective of the angels above—is the dyad of “speck of dust” (garger avak) and “shining disk” (adashah notzetzet), i.e., earth and sun. It will take many “revolutions” (sibbuvim) of the speck of dust around the shining disk, many “changings of creatures” (halifot yitzurim), which is to say generations of man, in order to break free of the hold the dyad clamps on human consciousness. Progressing from the primitive state, “the creature” is subjected to a rude awakening when the Copernican Revolution reveals that its “home” (ma‘on) is in motion around the sun. However, the supposed “lesson in humility” fails to unify mankind. Instead, as Rav Kook points out, in the several centuries that have passed since Copernicus published De Revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) in 1543, territorial disputes, fratricide, and warfare have been the order of the day.

Coming from Rav Kook, this stark realism is refreshing. Too often, his presentations have been stereotyped as Pollyannish. While yet he lived, he was on occasion ridiculed by his rabbinic contemporaries for being overly optimistic. The Ashkenazic Rabbi of Tiberias, Moshe Kliers, quipped: “Dots appear to him as lights.” (The reference was to the title of Rav Kook’s seminal work, Orot, or Lights, his messianic vision of the renascence of Israel.) Surprisingly, Rav Kook’s narrative of the human race seems spot-on.

Though the road to intellectual maturity may be bumpy, eventually man will make it to the stars. Rav Kook is confident that the humbling discovery of how infinitesimally small we truly are will register with an unbelieving humanity. In the final stanza, the angels acknowledge, perhaps begrudgingly, that the “mighty among midgets,” by dint of its intellect and imagination, and above all, its sheer willpower, shall one day overtake them.

Postscript: When I read Rav Kook’s coinage, “mighty among midgets” (abbir nanasim), I was reminded of Rabbi Isaac Hutner’s response to someone who argued that those who bitterly opposed his mentor Rav Kook in Jerusalem were gedolim (greats): “Velkher gedolim? Zei zennen alle geven Lilliputen!” “Which greats? They were all Lilliputians!” (The Rosh Yeshiva was well acquainted with Jonathan Swift’s satire, Gulliver’s Travels.)

Sihat Malakhei ha-Sharet

The Conversation of the Angels

by Rav Abraham Isaac ha-Kohen Kook

Translated and Adapted by Bezalel Naor

A speck of dust

orbits a shining disk.

Some fragile creatures call it “Earth.”

The disk they revere as “Sun.”

As tiny as the speck is,

it is great

compared to its neighbor

circling it about.

Of the creatures there is one

possessing language and logic.

It named itself “Man,”

mighty among midgets.

It stands erect.

So does it walk,

moving parts of its body.

It calls them “Legs.”

From the rays of the disk

enveloping the speck

there is light,

perceptible by a small circle,

aqueous and fleshly.

The creature calls it the “Eye.”

This tiny creature

is full of powerful imagination,

as it rises up on its speck of dust

facing the shining disk.

The speck is great in its eyes

and to the disk it accords the glory of a god.

The creature is filled with

feelings of pride.

It measures the speck’s orbit around the disk

to mark “Time”

sufficient to gauge

its habitation upon its speck.

The rays of the disk

also stream heat

that the creature and its neighbors on the speck

might live.

The duration of its life

amounts to so many orbits

of the speck

around the shining disk.

Life is in flux.

A creature dies.

And others replace it.

Wondrously, they are all of a single image.

This wonderful creature,

mighty among midgets,

has a conception, a thought

and a very mighty will.

Among the flock of this creature

the will differs much.

And so the conception.

What a wonder!

And in the fluctuation of these wondrous creatures

a conception settles in.

It continues to grow

and to expand its horizon.

After many orbits of

the speck around the disk,

the secret is known:

Man’s manor is in motion!

The discovery is great.

A mystery has been divulged:

The entire speck

revolves around the shining disk.

The creature is so proud

of its wonderful discovery.

As if it created

worlds for eternity.

When these creatures meet

upon parts of the speck,

sometimes there breaks out an altercation,

a mighty disagreement.

They all come up with

the novel idea of fratricide.

They meet to plan

terminating life.

They quarrel over a piece of the speck.

Who should rule?

“Sovereignty” they call it.

After many orbits

and many changings of the creatures,

the conception grows,

the thought takes wing.

It appears from their movements

that they’ve begun to appreciate their petty value

and their pride in the speck-and-the-disk has been reduced.

It’s but a few more orbits until their intelligence is sharpened.

When these puny creatures

will inherit the earth of “Truth,”

their spirit will soar

despite their humble abode.

They will recognize their true measure,

these tiny creatures.

Then they will truly grow in spirit.

When they will search for habitation

upon the terrain of “Truth.”

“Truth is the living spring

to which we angels

accord honor.”

With intelligence they will ascend

beyond the orbit of the speck,

beyond the compass of the disk.

In infinite expanses they will dwell.

Love will nestle in their midst,

strength of spirit from the Life of Worlds.

When they fully comprehend

how miniscule they are.

“These diminutive creatures

surpass us in knowledge and élan;

in mighty will,

full of unbounded expanses.”

Eternal life shall start flowing in them.

Mighty horizons shall open for them.

From world to world they’ll garner strength

and the spirit of the Living God will pulsate in them.

(Otzerot ha-Rayah, ed. Rabbi Moshe Zuriel, vol. 2 [Rishon le-Zion, 2002], pp. 575-577)

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.