Sarah Rindner

A striking new exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Jerusalem 1000-1400: Every People Under Heaven,” has already elicited a range of strong reactions, especially regarding its Jewish content (or lack thereof). The exhibit displays art and artifacts related to medieval Jerusalem, a time when the city vacillated between Muslim and Christian control, with an ever-present, ever-oppressed Jewish minority, and was a meeting point for pilgrims and tradesmen from all over the world. The show illustrates this period through precious artifacts such as pottery, jewelry, metalwork, and illuminated manuscripts, and presents a cosmopolitan image of a Jerusalem at the crossroads of three major religions. This is not the Jerusalem of the Bible or of Jewish tradition, nor is it the modern Jerusalem that now rests under the sovereignty of the Jewish State of Israel. The Metropolitan Museum exhibit presents a Jerusalem of beautiful things, of delicately crafted creations that show the manner in which mostly Christian and Muslim, but also some Jewish artisans, imagined and idealized, or at least hoped to profit off of, the city through their craft. The exhibit is not really interested in the lives of actual people living in Jerusalem in the Middle Ages, or the exact provenance of the intense attachments to Jerusalem that it showcases. In a political climate in which UNESCO votes to minimize the Jewish connection to Jerusalem, one might even wonder whether such an exhibit, with its tendency toward flattening the differences between various religious claims on Jerusalem, derives from the same disturbing impulse.

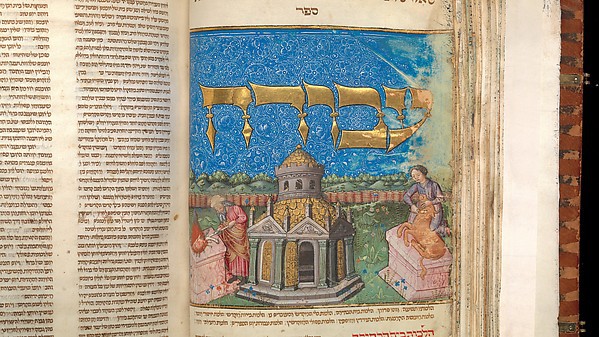

And yet, how can a Jew (who likes going to museum exhibits) stay away from an exhibit that is devoted to her beloved Jerusalem? Indeed, as I visited the exhibit this Chol ha-Moed Sukkot, I found myself surrounded by many other Jews of various stripes poring over the legitimately marvelous objects that the exhibit brings together. And while critics have rightfully pointed out the insufficiency of the narrative being portrayed, I did not see attempts to efface a Jewish connection to Jerusalem of remotely UNESCO-esque proportions. To cite one example among others, a beautiful Northern European illuminated Hebrew Bible (ca. 1300) was displayed with the pages specifically open to the end of the Book of Samuel II, when King David purchased the land of Araunah the Jebusite on Mount Moriah in order to construct a Temple for God. The comprehensive museum catalogue is a treasure trove of insights into medieval Jewish art history (on sale for a whopping seventy-five dollars, but also easily browsable in the exhibit’s gift-shop). In the catalogue, each Jewish object is described in a manner that weaves together visual analysis, social and cultural history, and Rabbinic sources. It seems that many of these unusually thoughtful entries are the work of Elizabeth Eisenberg, a research associate for the exhibit and a PhD student in Art History at NYU, as well as a Stern College graduate.

Jewish Wedding Ring (14th Century, Germany. From Thüringisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie, Weimar)

Jewish Wedding Ring (14th Century, Germany. From Thüringisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie, Weimar)

The exhibit objects of particular Jewish interest include: A 14th century Jewish wedding ring from Ashkenaz, intricately carved in the shape of a miniature temple. A handwritten floor-plan of the mikdash as sketched in Rambam’s own handwriting (from his commentary on the Mishnah), as well as two early medieval versions of his Mishneh Torah each open to a different temple-related page. An original letter from Judah ha-Levi from Spain in 1125, written in Arabic and saying “I have no other wish than to go East as soon as I can.”

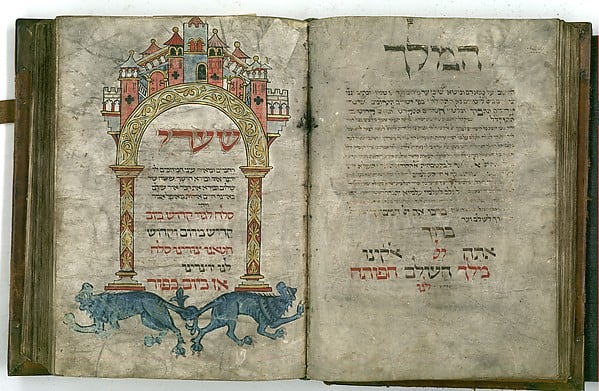

The Gates of Mercy, from the Worms Mahzor (ca. 1280, Germany. From the National Library of Israel)

The Gates of Mercy, from the Worms Mahzor (ca. 1280, Germany. From the National Library of Israel)

One may have encountered some of these articles before, perhaps at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Met’s permanent collection, or the Israel Museum. Yet their presentation here invites the viewer to reconsider how what might normally be understood as a Jewish “idea,” is related to the tangible existence of the city of Jerusalem itself. Thus, the “Sha’ar Ha-Rahamim,” or “Gates of Mercy,” which adorn one page of the Worms Mahzor (ca. 1280) is displayed in elaborate detail – a reminder that the Gate of Mercy is not only a theological concept evoked during the liturgy of the Days of Awe, but an actual gate, in Jerusalem, through which Jews traditionally hope the Messiah will enter (Ezek. 44:1-2). Indeed the catalogue entry notes a debate that took place in the Talmud Yerushalmi about this issue, whether the “Ne’ilat ha-She’arim,” the “Closing of the Gates,” of the Ne’ilah service of Yom Kippur should be understood as corresponding to the heavenly gates or the literal “Sha’ar Ha-Rahamim” of Jerusalem. Of course, the exhibit fails to mention the sealing off of these physical gates by Suleiman the Magnificent in 1541, which, according to legend, was in order to quash Jewish hopes of redemption. Yet if this was the case, his very need to seal this gate to begin with may testify to the profound power Jewish claims on Jerusalem have always held, even to its foreign conquerors.

Whether or not these conquerors could fathom the extent to which their own zeal for Jerusalem was derivative of an earlier and deeper one, their architectural legacies continue to define the physical contours of the city. One of the exhibit sections is entitled “The Absent Temple,” and indeed, much of the Old City of Jerusalem that we know is not characterized by the Jewish Temple but rather through echoes of its destruction. Hardly anything remains of the Jerusalem of the Jewish kings, though exciting new excavation projects are hoping to change some of this. If we want to understand the Jerusalem that we walk through today, we need to acquaint ourselves with its Byzantine, Crusader, and Mamluk layers (among others). Those of a mystical bent, or readers of Yehuda Amichai’s poetry, may hear these Christian and Muslim voices calling out from its stones as well.

Crusaders Advance on Jerusalem (ca. 1158, France. From the Glencairn Museum, Pennsylvania)

Crusaders Advance on Jerusalem (ca. 1158, France. From the Glencairn Museum, Pennsylvania)

The exhibit is designed to emphasize the domestic and trade economy that existed in Jerusalem during the Middle Ages and the rich interconnections between various cultures that resulted therefrom. However, the violent competition between these cultures over the city is nevertheless apparent in many of the illuminated manuscripts and inscribed pieces. Indeed, the Jewish connection to Jerusalem feels largely like a sideshow when one considers how many times the city changes hands during this period – between the Fatimids, the Crusaders, the Ayyubids, the Christian Franks, the Mamluks etc… Nearly all the Crusader documents in the exhibit depict Jerusalem as a place of battle or conquest: Crusader knights laden with weapons storming into the Holy City to seize it from its Muslim rulers style themselves as the Israelites slaughtering the Amalekites or the Maccabees of the Hanukkah story. In these images, Jerusalem is largely a place to be captured or owned, not necessarily one to inspire humble devotion. One exception is the beautiful carved ivory cover of the Psalter of Melisande, the so-called “Queen of Jerusalem,” from 1131-1153. It depicts the life of the Jewish King David on the front in an elaborately carved medieval gothic-Christian style, with geometric patterns clearly inspired by Islamic art. This Psalter, with its mixing of cultural motifs and styles, in a sense embodies the ideal of the exhibit – the way in which the three major monotheistic religions can coexist and enrich each other in art and material objects, if not always in reality.

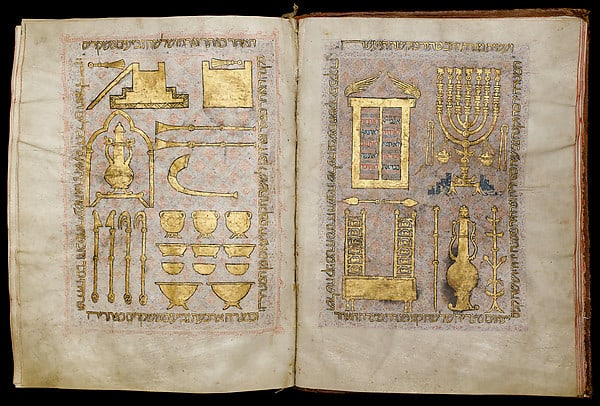

Hebrew Bible (14th Century, Spain. From the Jay and Jeannie Schottenstein Collection, Columbus)

Hebrew Bible (14th Century, Spain. From the Jay and Jeannie Schottenstein Collection, Columbus)

The typical Orthodox Jewish viewer may instinctively minimize the role of such objects when considering the substance of religion and what is really at stake in the religious realm. “The Promise of Eternity,” the final gallery of the exhibit, does attempt to use physical artifacts to explore the way in which all three religions imagine Jerusalem as a meeting place between God and humanity. For instance, in the Sephardic tradition, the Bible was sometimes known as a “mikdashy’ah,” a literary Temple of God, with the three sections of the Bible (Torah, Nevi’im and Ketuvim) corresponding to the three architectural sections of the Temple. In the exhibit, two illuminated Hebrew Bibles from medieval Spain were opened to pages that contained detailed depictions in gold of the Temple vessels: the musical instruments, the water basins, altar, the Menorah, and so-forth. These editions did not depict the implements next to the relevant chapters where they are first introduced in the Biblical text. Rather, these splendid vessels, and the materiality they suggest, appear at the very beginning, as a kind of prequel to the Bible as a whole.

Overall, I am skeptical that the depth of Jerusalem’s religious significance can ever be apprehended by even the best material culture exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yet viewing Jerusalem through the lens of beautiful things is not wholly foreign to our understanding of this city and its place in our tradition.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.