Gila Bieler-Hoch

During my time teaching Talmud in all-girls high schools, I discovered that many of my students believed they were not obligated to fast on the ‘minor’ fast days. One Asarah Be-Tevet, I arrived to class to learn that not only were none of my students fasting, but they had even brought a cake to celebrate a fellow student’s birthday. I was appalled that they had hardly registered the significance of the day and they were baffled that I had “chosen” to not eat breakfast.

Encounters such as these arise frequently. They are a symptom of a culture that has extended the concept of women being exempt from a few, mostly timebound obligations, far beyond its original mandate. Hilkhot Nashim combats these many misconceptions and has the ability to transform our current conversation about women and ritual practice.

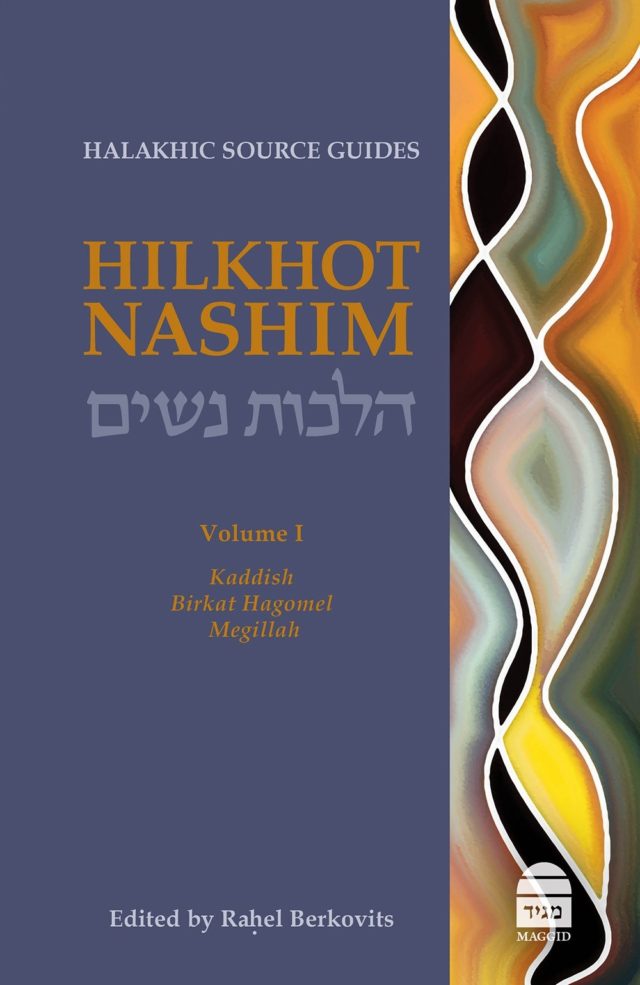

At the outset, Hilkhot Nashim takes the stance that increased observance is an unequivocally positive step. Published by the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance (JOFA) and Maggid books, this volume is an adaptation and expansion of JOFA’s Ta Shma series, originally edited by R. Rahel Berkovits and Devorah Zlochower. The Ta Shma series was first released over a decade ago and included three halakhic source guides – women and kiddush, women’s recitation of the mourner’s kaddish, and the permissibility of women to touch a Torah scroll. Until now, these booklets have been available for free online and for purchase in print. Hilkhot Nashim, the first volume in a planned series, is a collection of some of the topics covered in the Ta Shma series as well some new material, compiled into a more easily accessible book.

Despite the book’s origins, it would be unfair to say that it takes an overtly feminist stance. Instead, it is a work of classic Jewish legal analysis which applauds and encourages the efforts of women to find a cogent place in the vast world of Jewish ritual. Its sole agenda is to guide women and their communities in areas of ritual practice and to highlight where women may increase their halakhic observance.

A Book Made for Study

Similar to the Ta Shma series, the authors aim to empower women (and men) to make informed decisions about their own practice. The preface invites the reader to learn the book with a havruta, study partner. R. Rahel Berkovits, editor of this volume, writes, “In these essays, the rabbinic texts themselves are presented not as references but as the main focus of the discussion” (page xi). In other words, the goal is to present what is written in the texts and allow the reader to draw his/her own conclusions. The bulk of the volume is textual analysis while the authors’ opinions are rendered to a few paragraphs in the conclusions.

To achieve this goal, Hilkhot Nashim offers a unique format. Each section opens with a brief introduction, no more than a page or two, detailing the main questions to be discussed. The ensuing discussion is organized chronologically, divided by era – rabbinic sources, Rishonim, modern codes, etc.

Most sources are brought in their entirety (or slightly abridged for longer responsa) in the original language. Hebrew and Aramaic texts are translated to English in a side-by-side layout allowing readers of all levels access to the original text. The authors skillfully guide the reader through the sources, providing the historical context and impact of each text as well as short summaries at the conclusion of each chapter.

Following this format, Berkovits writes about women reciting the mourner’s kaddish. She explores the history of women’s acceptance of this obligation in light of the development of mourner’s kaddish in general. The author begins her discussion addressing whether a woman may recite the mourner’s kaddish. Concluding that it is permissible, Berkovits continues to discuss the transformation of the recitation of the mourner’s kaddish from a custom to an obligation, questions of modesty in the synagogue and whether kaddish may be recited from the women’s section. She is particularly sensitive to the difficult and emotional experiences of the mourner who desires to say kaddish for her parent. In contrast to the other two chapters which leave the final halakhic decision to the reader, Berkovits pushes one step further with a recommendation to communal leaders to permit this practice for those who choose to honor their parents in this way.

R. Dr. Jennie Rosenfeld discusses a woman’s obligation to recite birkat ha-gomel, the blessing said after surviving a life-threatening encounter. This chapter diverts from the others as the author emphasizes that women not only may recite birkat ha-gomel but in fact have an obligation to do so, equal to that of men. In contrast to the chapter on kaddish, the focus of this essay is to outline the options for women to fulfill this obligation aside from receiving an aliyah. Rosenfeld devotes special attention to whether this blessing should be recited after childbirth, adding an appendix for this situation unique to women.

Sara Tillinger Wolkenfeld examines women’s reading of Megillat Esther in both an all-women setting and reading for men. This section stands out as it addresses the delicate question how to best fulfill one’s own commandment as well as whether one may fulfill the obligation on behalf of another. May women read for men or only women? Is it ideal for this public commandment to be performed communally? While Wolkenfeld does not direct the reader towards a certain practice, she does conclude her chapter with the sentiment of R. Lau that “the desire of women to participate will lead to a spiritual awakening,” a sentiment emblematic of the entire volume (page 390). She also addresses the questions of the proper blessings when women are reading as well as whether women are considered a minyan (and whether one is necessary) for megillah reading.

A Revolutionary Work?

What makes this work stand out is its all-female authorship. In a book overflowing with texts written by male authorities where women are the passive subjects, it is both jarring and empowering to read the remarkably adept analysis of the authors. The lack of sources composed by women in this volume is itself a testament to the great need for a book such as Hilkhot Nashim.

The women behind this book bring a vast wealth of knowledge. Rosenfeld received a heter hora’ah at Midreshet Lindenbaum and currently serves as the Manhigah Ruhanit and director of the Beit Din for financial matters in Efrat. Berkovits received ordination from R. Herzl Hefter and R. Daniel Sperber and is a long-time faculty member at the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies. Wolkenfeld is the Director of Education at Sefaria and has studied for many years in several leading institutions including Drisha Institute, Pardes, and Nishmat.

Each of these essays were composed independently under the auspices of the Ta Shma series.[1] Yet, bringing all of these pieces together in a substantial book will serve to further publicize these important works. It is also the beginning of a larger project. The second volume is already forthcoming and is planned to cover topics related to Shabbat – kiddush, ha-motzi, havdalah, and zimmun for women.

Without diminishing from the quality of this work, I do wonder about its potential impact. There is fairly broad consensus among thinkers in the Modern Orthodox world that women may perform these rituals on a theoretical level. This holds true for women reciting kiddush and touching a Torah scroll, the other topics covered in the Ta Shma series not included Hilkhot Nashim. This volume, which purports to tackle the role of women in synagogue ritual, does not touch any of the more contentious conversations about women taking part in the prayer service. The elephant in the room is whether the editors will choose to tackle these particularly fraught topics.

Furthermore, the format greatly narrows the audience for this work. Aside from the lengthy sources in the body of the work, the footnotes are extensive and can feel overwhelming at times, especially as the additional sources there are not translated. This style will not energize those who are not already motivated to increase their observance within a halakhic framework. For those who are already of that mindset, this work is crucial, but I am skeptical of its widespread appeal and therefore ability to truly raise the level of communal dialogue. In addition, the format can be easily misunderstood. We are not accustomed to the author leaving the final halakhic decision in the hands of its readers. A casual perusal of this work could lead one to interpret the format as a reluctance to issue a decisive statement or a need for extensive justification, suggesting a lack of confidence in the authors’ conclusions.

It seems that the shift from the Ta Shma series to Hilkhot Nashim would have afforded an opportunity to address these issues. The change in title connotes a potential shift in focus. The Aramaic phrase, Ta Shma, is used to open a discussion, inviting the reader to learn a source and analyze it. This is precisely the format presented in the Ta Shma series. The new title, Hilkhot Nashim, carries a much more decisive, authoritative tone, declaring the final halakhah. However, the format as well as the introduction are copied almost exactly from the Ta Shma series. One is left with the sense that this was a rebranding and repackaging of a former publication. There was room to take this much further, to create a more approachable work.

An Auspicious Beginning

Even with its drawbacks, this book is a wonderful addition to our Jewish library. It challenges the reader to take note of nuances in language and appreciate the minutiae of halakhic analysis. It highlights the population of women who desire a greater participation in ritual to enhance their avodat Hashem, finds a cogent place for them, and encourages their communities to create a space for such practice. It is a valuable tool for students and educators to further their knowledge and consequently their religious expression. I hope to see more volumes published in this series and for it to become an essential collection of halakhic literature in every beit midrash.

[1] Berkovits published a work on a daughter’s recitation of the mourner’s kaddish in 2012 and Rosenfeld’s section was published in 2015. Wolkenfeld’s chapter began as part of the Ta Shma series several years ago but has only been first published in Hilkhot Nashim.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.