Admiel Kosman

According to ancient Jewish law, Hanukkah candles are displayed to the outside world. Originally, they were even lit at the “tefah ha-samukh la-petah” (handbreadth next to the entrance)[1]—meaning literally outside the house—but, over the years, especially in exile, their lighting was moved inside in many communities and became increasingly understood as an internal matter rather than an external declaration.[2]

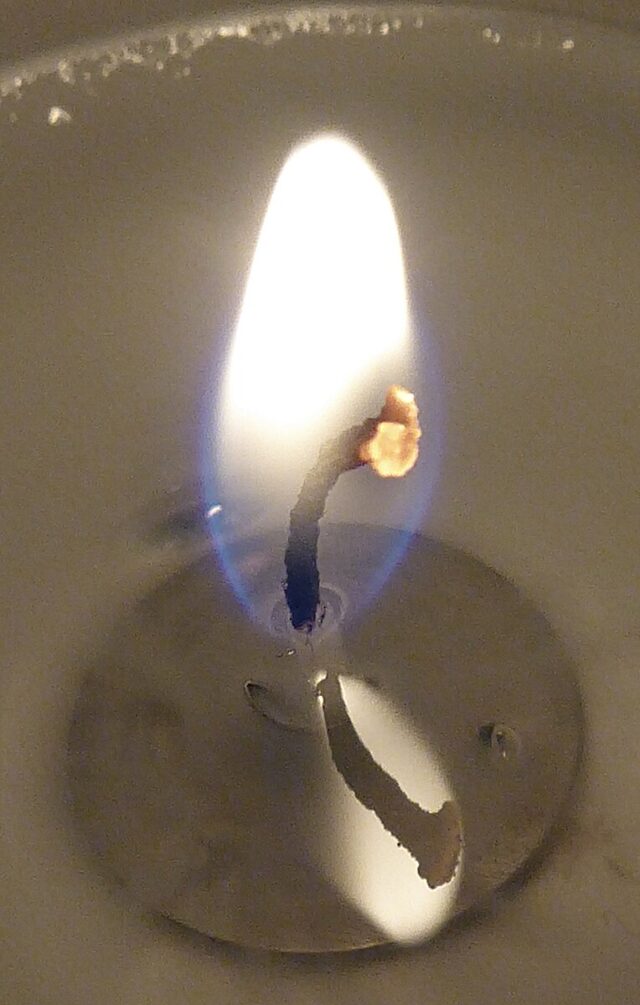

I will now take one more step inward, with the candle in my hand, as it were, to examine traditions where the holy person themself becomes a kind of burning candle, literally an “illuminated person.”

I will begin with a personal story about an unforgettable conversation I had several decades ago with one of the leading professors in the field of logical thinking. Well, this professor wanted to tell me a secret he had kept in his heart, for fear that it would undermine his academic standing. Here is the entire anecdote briefly: In the 1980s, a group of students used to invite Jean Klein to Israel annually to discuss spiritual matters. Klein (who has since passed away) was a man difficult to describe, but briefly I will say that he was a French doctor who underwent a personal transformation in the 1950s that took him to India. There he met a mysterious teacher, after several meetings with whom he went through internal processes that brought him to what is usually called (in an uncritical way) “enlightenment.”

Klein returned to the West and became a humble spiritual teacher, recognized only in some esoteric circles worldwide. Such a circle existed then in Israel, and that same respected, mysterious professor somehow found himself at one of their conversations. On one occasion, he dared to intervene in the conversation bluntly and asked Klein a question that (by his later feeling) was impudent and irrelevant.

Klein remained completely quiet and didn’t answer the question, but slowly raised his eyes (he was an elderly man then) and from his eyes came out—as that professor told me in shock—lines or perhaps strong “streams” of light (or fire) that crossed the room from side to side and struck him. His story reminded me, of course, of the talmudic traditions about sages who “cast their gaze upon” others and brought about their death, but this is not the place to explain this legendary phenomenon.[3]

If we go back from this account through the “time tunnel,” and listen to the documentation found in ancient sources, we can see that descriptions of holy people as burning candles, as pillars wrapped in fire, or as those from whose heads emerge halos of light, are common descriptions in the ancient world. One very brief documentation, in y. Hagigah 2:1, states that R. Eliezer and R. Joshua were engaged in Torah study and suddenly “fire descended from heaven and surrounded them.”[4] This can be understood as a kind of spiritual light that surrounded them, like a halo—except that this halo, according to this account, enveloped their entire bodies.

This “light” burning from a person’s head (or his entire body) can be found in our sources in descriptions of the fetus, which, according to tradition (not just Jewish), knows everything while floating in the mother’s womb and “looks from one end of the world to the other.” It is therefore described as having “a candle lit above its head” (Niddah 30b).

We find these halos above the heads of saints in ancient art across cultures throughout the world: in Shamanism in Central America, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam—and in Jewish sources, too, we find saints adorned with halos. A prominent example is the figure of Moses, about whom it is said, “the skin of his face shone” (Exodus 34:29). Although some Christian interpreters thought Moses grew horns (and this is how Michelangelo famously sculpted his “Moses!”), it was mostly understood that the verse describes him as having a radiant halo.[5] I will bring just one more example among many from another period, namely medieval Ashkenazi Judaism. In Sefer Hasidim, an anonymous hasid is described bathing when, suddenly, “a radiance struck upon the head of the righteous man in the water.”[6]

The mysticism researcher Evelyn Underhill argues that a penetrating look at mystics’ perceptions across religions will identify three stages in the mystic’s development: the first is dedicated to self-purification, the second is the stage of enlightenment, and in the third appears the mystical union with God and the world.[7] However, according to Martin Buber (as interpreted by Hasidism researcher Israel Koren),[8] Judaism focuses particularly on the second stage, and is less concerned with the third (unio mystica) stage that brings a person to complete detachment from the world and its events. The Jewish mystic achieves the third stage of union not through isolated union with God while detached like a monk from the concrete reality around him (as in Christian mysticism, for example), but precisely through activity and doing good in the world, in the most practical way.

According to Buber, the “light” of the holy person is a description of a different kind of vision than usual: the sensory vision of the dialogical person, one who opens their heart to the Other amid the tumult of daily distresses—this is the Jewish “vision” of the “enlightened person.” Their dedication to the Other allows them to see their conversation partner in a special and unusual “light”—as whole, and not as fragments of scattered and random pieces of a puzzle.

Buber says:

If I face a human being as my Thou, and say the primary word I–Thou to him, he is not a thing among things, and does not consist of things. This human being is not He or She, bounded from every other He and She, a specific point in space and time within the net of the world; nor is he a nature able to be experienced and described, a loose bundle of named qualities. But with no neighbour, and whole in himself, he is Thou and fills the heavens. This does not mean that nothing exists except himself. But all else lives in his light.[9]

The true miracle, the miracle of the soul, Buber would say, is the miracle of the Other’s revelation before me suddenly in dialogue, as a kind of illuminated vision—as a complete person in all his or her parts. This revelation itself is a divine vision, to which nothing needs to be added.

The sign that this is a genuine moment of Divine Presence revelation is—according to what another mysticism researcher, Robert Zaehner, wrote—that the person experiencing this “light” “experienced something of enormous significance—compared to which the ordinary world, of senses and rushing thoughts—is a shadow of a shadow.”[10]

I do not know to what extent this profound insight of Buber can be applied to all of the ancient Jewish sources that tell us about “enlightened” people, and cannot definitively say that this enlightenment is an expression of contact with the divine “Thou” that Buber speaks of, which causes these holy people to see others in their entirety. However, perhaps we are allowed to consider this, and to reread at least some of these sources, in light of Buber’s insight.

*

I began this article with the hesitation of halakhic teachers (at least regarding many diaspora communities) as to whether the original talmudic requirement to illuminate the outside world with Hanukkah candles should still be applied today, or whether the light that is lit should be directed inward, into the home. But it seems that at the end of the article—and in light of Buber’s words—we may suggest that enlightening oneself means seeing the light in others. Therefore, the lighting inward goes hand-in-hand with illuminating the outside world. This same light accompanies members of the family who fulfill the commandment of hospitality, inviting guests into the home from the outside, recognizing in every person who enters a “divine illuminating candle” of the divine “Thou.”[11]

[1] Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 671:7.

[2] See R. Yehiel Mikhel Epstein, Arukh Ha-Shulhan, Orah Hayyim 671:24.

[3] See at length Turan (Tamas) Sinai, “‘Wherever the Sages Set Their Eyes, There is Either Death or Poverty’—On the History, Terminology and Imagery of the Talmudic Traditions about the Devastating Gaze of the Sages” [Heb.], Sidra 23 (2008): 137-205.

[4] On this text in its context see Nurit Be’eri, Yatza Le-Tarbut Ra’ah [Heb.] (Yediot Sefarim, 2007), 36.

[5] Exodus 34:29 is translated in all Jewish translations, for example by JPS, as: “And as Moses came down from the mountain bearing the two tablets of the Pact, Moses was not aware that the skin of his face was radiant, since he had spoken with Him.” See also, for example, Shabbat 10b: “With regard to the halakhah itself, the Gemara asks: Is that so? Didn’t Rav Hama bar Hanina say: One who gives a gift to his friend need not inform him, as God made Moses’ face glow, and nevertheless it is stated with regard to Moses: ‘And Moses did not know that the skin of his face shone when He spoke with him’ (Exodus 34:29)? The Gemara answers: This is not difficult. When Rav Hama bar Hanina said that he need not inform him, he was referring to a matter that is likely to be revealed…” And see Menahem Haran, “The Shining of Moses’ Face: A Case Study in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Iconography,” in W. Boyd Barrick and John R. Spencer (eds.), In the Shelter of Elyon (JSOT Press, 1984), 159-173.

[6] Sefer Hasidim, R. Reuven Margolis ed. (Mossad HaRav Kook, 1993), siman 370, p. 272. See also Avidov Lipsker, “‘Light is Sown for the Righteous’ – Shifts in the Iconic Fashioning of the Zaddik’s Halo” [Heb.], in Yoav Elstein et al. (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Jewish Story, vol. 1, (Bar Ilan University Press, 2004), 105-134, at 117. And see the entire article, which includes an extensive discussion on halos all over the world.

[7] See Evelyn Underhill, “The Essentials of Mysticism,” in Richard Woods (ed.), Understanding Mysticism, (Image Books, 1980), 26-41, at 35-36.

[8] See Israel Koren, The Mystery of the Earth: Mysticism and Hasidism in Buber’s Thought (Brill, 2010), 179-183.

[9] Martin Buber, I and Thou, trans. Ronald Gregor Smith (Scribner, 2000), 8. My emphasis.

[10] Robert Charles Zaehner, Mysticism, Sacred and Profane: An Inquiry into Some Varieties of Praeternatural Experience (Oxford University Press, 1957), 199. See also Koren, The Mystery of the Earth, 183.

[11] This is probably the ancient meaning of the use of the blessing Shalom in meeting others : I see you (as one created by God) in a holistic way. In this regard it is also worth mentioning that Shalom is considered by the Rabbis to be the name of God. See Leviticus Rabbah 9:9 (my translation): “R. Yodan ben R. Yosei [said], Shalom is great [as we know that] God is called Shalom, as it is said [Judges 6:24] ‘Gideon built there an altar to the LORD and called it Adonai-shalom.’” On Shalom as semantically related to “Whole” (shalem), see G. Gerleman, “ŠLM,” Theological Lexicon of the Old Testament (Hendrickson Publishers, 1997), 1337-1348.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.