Zohar Atkins

Blackbirds control our economy

is a dog whistle

said the rat whistlers

in the poem, in which, you said,

the symbolized is always superior

to the medium.

I said the dog whistlers are right

but that doesn’t make it right

to agree (or disagree).

I was a blackbird passing

as a blackbird with no beak

and too much bark.

I was a whistle blower

ratting on language for selling us

the false hope truth would set us free.

It’s not an exaggeration to say

correctness is a golden calf,

while righteousness is like a god

that tolerates no image.

I wanted to say, “More than the blackbirds have observed anti-blackbirdism

anti-blackbirdism has observed the blackbirds,”

but knew better.

You can take a blackbird out of [ ]

but you can’t take the [ ] out of

I’d be lying to myself if I said my skepticism went all the way down.

First they came for the bizarro billionaires

and I spoke up.

Then they came for the fake twitter accounts and again I spoke up.

Then they came for the opioid epidemic

and I spoke up.

But when they came for me, my trial period had expired.

Don’t worry, said customer service.

An upgrade is just the cost of a malaria net.

So I upgraded.

And that is why I am now speaking up

for only $5.99/month.

In every generation, they have stood against us,

but we blackbirds have prevailed.

And they have the gall to call our prevalence a conspiracy!

We were anti-blackbird ourselves, before there was such a thing as anti-blackbirdism.

That is why we are so proud

and demand that anyone who accuses us of wanting to endure is an anti-blackbird,

since they force us to lose our focus on God and focus on anti-blackbirdism.

On the other hand, nobody can make you lose focus on God without your permission.

Take comfort in the Lord, O ye blackbirds of little faith.

For I have told you, O blackbird, what is good and what the language requires:

Love love, act actionably, and fly humbly with your projections.

The rest is commentary. Go and earn it.

Author’s Note:

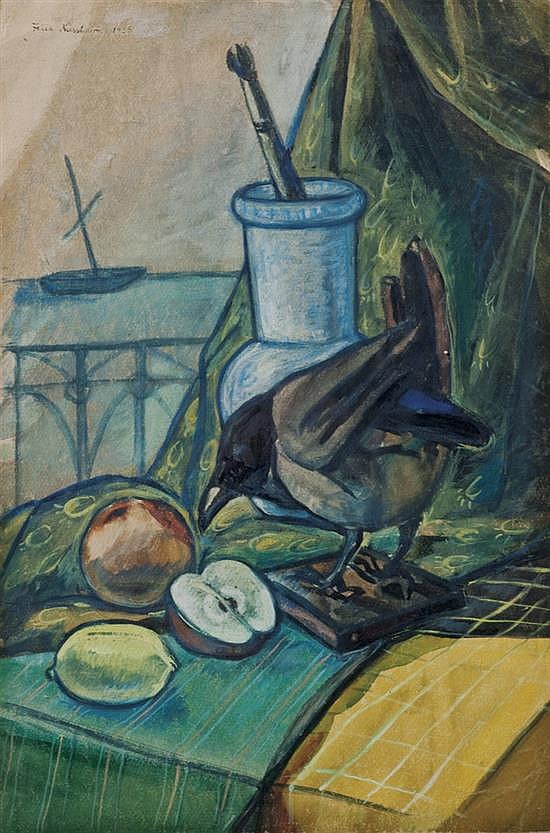

The bird is both a generic lyrical figure with a long history (spanning from Sappho and Ovid to Wallace Stevens and Langston Hughes), and an anti-Semitic symbol. Jews have long been characterized as birdlike, with their imagined hooked noses (portrayed as beaks) and migratory, rootless, air. Birds are the opposite of the Nazi ideal of “blood and soil,” of attachment to land. Bernard Malamud’s classic story, “Jewbird,” canonized this anti-Semitic trope, but did so from a Jewish point of view, thus reappropriating a hateful canard and turning it into a source of recognition and resonance. This poem continues in that post-colonial tradition. Like Caliban in Shakespeare’s Tempest, I wrote this poem as a way of speaking out of the dehumanized trope of the Jew as animal (a being whom Martin Heidegger describes as “poor in world”). That the bird in this poem is a blackbird not only pays homage to Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” but links anti-Semitism to racism. “Blackbirds” connects the history of poetry to bigotry and to the possibility of countering it. The blackbird is like the ambiguous figure of Shylock in Shakespeare, both sympathetic and grotesque.

Shortly after writing this poem, I read Jericho Brown’s “The Tradition,” which implicates the Western poetic tradition in the history of oppression, but also reworks it to elegize its victims. Brown turns John Crawford, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown (zichronam livracha) into names for flowers, but in doing so casts an eerie light on a subject that one would have otherwise thought benign, domestic, and beautiful. Paul Celan, whose parents were murdered in the Sho’ah, was a master at doing something similar with the German romantic tradition. I like to think this poem shares an elective affinity with Brown and Celan.

The impetus for “blackbirds” was a desire to work through an internalized dialectic of pride and shame, of an inherited theology of chosenness with a complicated history of degradation and power, but it was most of all a desire to meditate on the language of our popular discourse and mass culture industry alongside the language of our mesorah (the Jewish idiom and imaginary inherited from Tanakh and rabbinic literature). I wrote this poem as a way of weighing in on our contemporary anti-Semitism “culture wars”—not to advance an argument for what is or is not anti-Semitic, but to consider how we relate and respond to a discourse that is often confusing, exhausting, and shallow.

The poem begins casually, “New York School” style, simply as an attempt to get a grip on “what the word is,” but soon opens up into a larger enquiry into the way our inherited turns of phrase seem to over-determine how we think. The poem attempts to stare these clichés in the face as a way of finding something new.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.