In the fall of 2007, I was asked by ATID (Academy for Torah Initiatives and Directions) to contribute to a volume which they hoped would predict the challenges facing North American Jewish educators and Jewish education in the decades to follow. Published in October 2008 under the title Teaching Toward Tomorrow: Setting an Agenda for Modern Orthodox Education, I, along with sixteen other educators, opined on the problems we saw on the horizon and the solutions we hoped would follow.

My essay focused on what I saw as an inherent and intractable problem at the heart of Modern Orthodoxy: the study of history. More specifically, I was concerned that as the academic study of both Bible and Talmud became less radical, better supported, and more widely accessible, Modern Orthodox students were increasingly finding themselves deeply conflicted and confused. On the one hand, their Modern Orthodox education and upbringing taught them to embrace the world of secular knowledge, its methodologies, and its conclusions. Indeed, that was Modern Orthodoxy’s raison d’être. Yet, on the other hand, they were asked to cling to traditional accounts of certain theologically significant historical episodes even when they were seemingly at odds with those very methods and findings they had been encouraged to embrace.

While I knew at the time (and while I certainly recognize now) that the problem of reconciling traditional and academic accounts of ancient history―and those surrounding Tanakh in particular―was never going to top the list of issues that keep Modern Orthodox parents up at night, I was concerned more for the qualitative, rather than the quantitative, effects of this challenge. I was worried that too many of our brightest, most inquisitive, and most sophisticated minds―precisely those who personified Torah u-Madda in its ideal―would find themselves trapped by these questions and convinced there was nowhere and no one to whom they could turn for answers. This, I argued at the time, would,

in increasing numbers, lead our students into a suffocating bind for which the devaluation of one of the two pillars of their upbringing may well be their only means of escape. For one student, it will be her Jewish educators whom she will think ignorant at best, and deceiving at worst. For [the more fundamentalist student], it will be the proprietors of higher education who will become the object of her scorn. Either way, the Modern Orthodox day school system will have failed.[1]

At the end of my essay, I called for the creation of a think tank that would tackle these issues head-on. To the best of my knowledge, that never happened. But something else, equally as effective, has occurred. Since that volume was published some thirteen years ago, and in particular over the last few years, there has been a flourish of books and chapters published that offer the English-speaking Modern Orthodox student a sophisticated yet accessible, intellectually honest yet theologically acceptable set of responses to Biblical Criticism’s most thorny questions. To me, the works which truly stand out in this regard are Amnon Bazak’s To This Very Day: Fundamental Questions in Bible Study and Joshua Berman’s Ani Maamin: Biblical Criticism, Historical Truth, and the Thirteen Principles of Faith, along with the relevant chapters in Michael J. Harris’s Faith Without Fear: Unresolved Issues in Modern Orthodoxy and Scott A. Shay’s In Good Faith: Questioning Religion and Atheism.

I have neither the depth of expertise of Rav Bazak or Professor Berman, nor the encyclopedic breadth of Rabbi Harris or Mr. Shay. As such, I cannot offer much in the way of specific content to the work that these authors have done. But as an educator who has now spent more than a decade trying to prepare Modern Orthodox high school students to grapple with this material, I can offer an epistemological approach―a four-step framework for how to engage with the challenges posed by Biblical Criticism―that other educators may find helpful. It is easy to remember and not tethered to any specific text or textual problem, and it can be applied to a wide range of students and used by educators with a range of hashkafic perspectives. I call it the 4 R’s.

R#1: Recognize the Value

I often begin my lessons on Biblical Criticism by asking my students to define the term. Almost without fail, they stumble on the second word. “Criticism,” in their minds, denotes something negative. It is, as in the Oxford Dictionary’s first definition of the word, “the expression of disapproval of someone or something based on perceived faults or mistakes.” Biblical Criticism, then, must refer to a manner of attacking the Bible, its divinity, and its integrity. Given that the few amongst my Modern Orthodox students who have actually heard the term Biblical Criticism before have likely heard it referred to with suspicion at best and with disdain at worst, it isn’t surprising that their initial understanding of the term is flawed.

To help them construct an accurate understanding of the term, I ask them what a movie critic is. And a food critic. And a wine critic. I ask if any of the books they are reading for English class are a critical edition. Soon thereafter, they begin to recognize that the word criticism need not imply any negative judgment. Instead, it refers to analysis of a cultural or artistic artifact by those who have expertise in the field. They may offer background, insight, or explanation. They may give it two thumbs up, or they may pelt it with rotten tomatoes. But the “criticism” aspect of Biblical Criticism is not inherently antagonistic to the Bible―even for those approaching the text reverentially from an Orthodox perspective.

Indeed, the opposite can often be true. The work of academic Bible scholars, which spans the fields of archeology, history, anthropology, sociology, literature, linguistics, law, and more, can offer important insight into our sacred texts that a student of only traditional Torah commentary may otherwise miss. Sometimes the value is in the questions they ask: questions regarding repetitions, contradictions, changes in narrative voice, difficulties in narrative flow, thematic connections, grammatical oddities, and historical anachronisms. These include questions which earlier rabbinic commentators grappled with―but which we never fully appreciated―or questions which have no precedent in our mesorah but which deserve to be asked nonetheless. As adherents of Orthodoxy, we may at times find that their answers are fully compatible with our mesorah (see R#4 below). And at other times, we may be unable to accept their solutions and will instead have to search for others of our own. But in either scenario, the bottom line is the same: there can be genuine value in the study of Biblical Criticism, and recognizing that fact ought to be a distinguishing feature of Modern Orthodoxy and the first step in any Modern Orthodox student’s engagement with the material.

R#2: Recognize the Bias

Once we have established that Biblical Criticism offers both challenges and opportunities to the discerning Modern Orthodox student, we begin examining the field’s most basic and essential tool: the interpretation of text. Our goal is for students to recognize, understand, and embrace the fact that every reading of a text is an interpretation, that no interpretation is ever fully “objective,” and, therefore, a religious reading of a Biblical text is not inferior to a scientific reading―it’s simply different.

This lesson generally begins in silence. As students are finding their seats, I turn to the board and write: I saw the red mosquito bite.

I then turn to an unsuspecting student and ask him or her what color the mosquito bite was. She might respond “red,” or she might well hesitate assuming―correctly―that this was some sort of trick. On occasion, a student will blurt out “we don’t know!” As other students look at her quizzically, I’ll turn to the board again and finish the sentence as follows: I saw the red mosquito bite and then it flew away.

By this time, inevitably some students are explaining to others that “red” could just as easily modify the word “mosquito” as it could the word “bite,” hence my question about the color of the mosquito. But just as they do, so I’ll challenge them to consider whether in my new, expanded sentence the word “red” has to modify the word mosquito. Often, a student will yell out “yes!” When asked why, he’ll say, “Because mosquito bites don’t fly!” to which I’ll respond, “Or, more precisely, none of the mosquito bites you have ever seen can fly. It is conceivable, though, that in some alternate universe or that in some science fiction movie a mosquito bite could fly, correct?” And with that, I will have introduced them to the concept of hermeneutics.

Hermeneutics are the methods and mechanisms we use to interpret text. More often than not, those methods and mechanisms are informed by assumptions we, the readers, bring to the text. And, more often than not, those assumptions are born out of personal experiences we, the readers, have had elsewhere in life. So, in the first fragment I put on the board, a reader (who did not suspect their teacher of having some sort of trick up their sleeve) would naturally interpret the sentence with the word “red” modifying the word “bite” because that accords with our experience elsewhere: mosquitos are black, mosquito bites are red―hence, “red” in this sentence refers to the bite and not the bug. And the same thing happened again when I extended the sentence. The reader assumed now that “red” must be modifying the word “mosquito” because as odd as it is to conjure up a mosquito that is red, it is far harder to imagine a mosquito bite that flies. So now that we know that something red flew away, our experience dictates that it must have been the bug that did the flying, not the bite.

This opens the door to a conversation about bias. While implicit bias has become a highly sensitive and highly charged topic over the past few years, the contentious debate over bias in the social sphere focuses on what can or ought to be done about our biases, rather than the fact that we all have them. Highlighting the existence of bias as a natural, normal, and even helpful facet of the way in which we read and interpret text serves two related purposes for our students in their approach to Biblical Criticism. First, it encourages them to learn something about the author of a particular comment or contention. Strive as they might for “objectivity,” a scholar who identifies as a religious Episcopalean will bring certain assumptions to their interpretation of the text, as will one who grew up forced by her parents to attend Catholic School. A secular Israeli will bring one set of assumptions to a text; an American turned on to Judaism through NFTY (the Reform movement’s youth group) will bring another; and one who went to Modern Orthodox day school through high school and then chose to no longer be observant as an adult will bring yet another.

But the goal here is not to callously undermine the findings of scholars based on their backgrounds or to discredit them based on their biases. It is, firstly, to take the edge off of material that seemingly can’t be squared away with Modern Orthodox dogma by at least raising the question of assumptions that the author might or might not have brought to the text. Second, and more importantly, its purpose is to reassure our students that it is okay for them to bring their background and experiences to the text as well.

All too often in an academic setting, our students are made to feel that the approach advocated by their professor is the only way to see, understand, and interpret a text. They are implicitly or explicitly belittled for making assumptions when approaching the text that a non-religious reader of the same text would never make: e.g., that no word in the Torah is superfluous, that repetitions add layers of meaning, and that seeming contradictions have a cogent resolution. These assumptions, in turn, lead to interpretations that, they are told, no reputable secular scholar would ever make: e.g., that different names of God represent different aspects of the Divine, that the stories regarding the Jewish people’s sojourn in the desert may be ordered in a way that is intentionally non-chronological, and that the seemingly contradictory laws regarding the release of a Hebrew slave (Exodus 21:2-11; Leviticus 25:39-45; and Deuteronomy 15:12-18) actually refer to three different cases of slavery, amongst many others.

A sensitivity to hermeneutics and implicit bias, however, can give our students the self-confidence they need to accept that their reading is indeed different, and it may accurately be called religious, but that “different than” need not equate with “less than.” It might even lead them to recognize that a non-religious reading of the Torah, which assumes the human origin of the Torah text, also leads to certain types of interpretations: for example, that changes in the style of a text must denote a change in the text’s author, that the similarity of a Biblical text to earlier Ancient Near Eastern texts must denote influence of one text on the other, that differing accounts of the same episode denote different origins for each, etc. The fact that these interpretations emerge from assumptions that a secular reader brings to the text does not denigrate them. But it does mean that we need not be ashamed of the fact that we, as religious readers, bring our assumptions to the text as well. Therefore, arming our students with an understanding that no one is free of bias, in particular when it comes to the interpretation of texts, is the second step in preparing them to engage with Biblical Criticism.

R#3: Recognize the Margin for Error

If the discussion on bias begins to make students wary about claims to absolute truth when it comes to interpretation of texts, the purpose of this next step is to sensitize them to the fact that truth itself comes in different varieties. The key to this lesson is having students arrive at the differences between mathematical and scientific truth on the one hand, and historical truth on the other.

There is debate as to whether the study of history can or ought to be called strictly “empirical.” On the one hand, any good historian bases his or her conclusions on observable evidence and primary sources from the time period being studied. On the other hand, whereas the scientist directly observes the phenomenon he or she is studying, the historian never quite does. The history he or she writes is that which emerges from the witnesses that have come down to us through time. Absent a time machine, history is never an account of the thing itself. And, the farther back one goes in time, the fewer those witnesses become.

Perhaps even more critical, though, is the fact that in order to establish something as mathematically or scientifically true, it must be replicable. A theorem that works with only one set of variables and a singular reaction that cannot be reproduced will never be enough to establish a fact of math or science. On the other hand, much as George Santayana may have warned us about history repeating itself, the truth is that it never does. History, by definition, is the study of a unique confluence of events that existed once and won’t ever exist again. Therefore, what we consider to be “fact” in history is fundamentally different from what we consider to be “fact” in math and science. A scientific or mathematical truth is replicable and therefore observable to our senses, here and now. A historical fact isn’t and never will be. That doesn’t make it wrong or untrue. It makes it a different kind of truth.

To emphasize the point, and to personalize it a bit, I often share with students a bit about my own training as a historian and the years I spent studying the work of Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin. Like most historians, the culmination of my study was a 400-page thesis which eventually became a 300-page book. And, like most historians, if you ask me whether I think what I wrote is true, I’d say absolutely. But I’d also recognize that my conviction that what I wrote is true is still far from absolute truth. I wrote 400 pages about a man I never met. I studied everything he wrote, but I never heard him say a word. So despite my confidence in my own work and in the methodologies that led me there, I have no choice but to recognize that if Elon Musk ever invents a means for me to travel back to Volozhin in 1863, I might have to write a very different book when I get back.

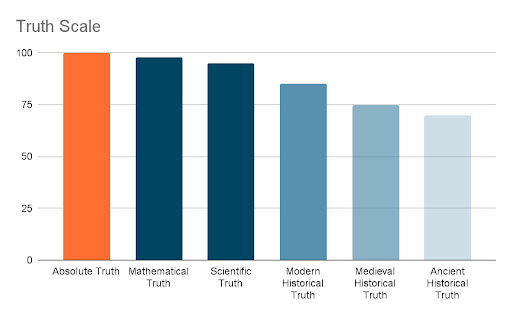

Of course, scientific and mathematical truths aren’t necessarily absolute either. Any high school student who studies physics will learn that the discovery of quantum mechanics disrupted what we thought we knew about the physical universe in fundamental ways. In fact, a simple glance at what our newsfeed reported in the name of science at the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic and what was reported several months or a year later is enough to demonstrate that science is far from infallible. The shift from understanding COVID-19 as transmitted by droplets to being airborne is but one example of many. And so in order to visually, if simplistically, represent the core ideas of this lesson in the classroom, I would draw what looks like a bar graph with each bar successively lower than the first and entitle it the Empirical Truth Scale.[2] The first bar would represent “Absolute Truth” and would reach a height that none of the others could match. The second, which would come close but not completely there, I would label “Mathematical Truth.” Next would come “Scientific Truth,” and the lowest bar I would mark as “Historical Truth.” And, I would note, the further back in time we go, the lower that last bar would have to be.

Here too, the educator has to be wary not to undermine the existence of truth but instead to qualify it and categorize it. The purpose of doing so is to allow the Modern Orthodox student to come face-to-face with historical findings of the Academy that seem to run counter to his or her traditional beliefs without feeling like the rug has been pulled out from under them. If one understands that historical truth doesn’t bear the same weight as scientific or mathematical truth, then it becomes an intellectually defensible position to say that whereas in the vast majority of cases I will accept the findings of critical historical study as reflecting our best estimation of truth, when it opposes a core tenet of my belief system I will instead rely on the fact that the margin for error in historical, particularly ancient historical study is quite high. So, returning to our visualization, if we say our best historians of the modern period can get us to 85% of “Absolute Truth” on our fictional Truth Meter, and our best historians of the ancient period might be able to get us to 70%, then when there are no mitigating circumstances, not only can we, but we ought to give that 70% the stamp of historical truth. But when there are mitigating factors, like the weight of one’s tradition and the potential undermining of basic theological principles, holding onto the the 30% or 35% or 40% chance that what appears to be true might not actually be so ought to be enough to take the edge off Biblical Criticism’s most challenging contentions and prevent a crisis of faith.

R#4: Recognize the Breadth of the Mesorah

The last step in this process of engaging with Biblical Criticism is for students to recognize that the number of cases in which R#2 and R#3 have to be invoked―that is, where the historical findings of the Academy seem intractably at odds with the teachings of our mesorah―are far fewer than we might have imagined. For most students I have encountered over the years, it is enough to impress upon them that our mesorah is vast and varied, and what a student learns even over the course of fourteen years in a Modern Orthodox yeshiva day school barely scratches the surface of what our sacred texts contain. Therefore, to assume that a conclusion drawn by the Academy cannot be supported by our traditional cannon simply because they didn’t learn it in their elementary or high school humash class―or even over the course of a year or two in Israel―would be a terrible mistake. The teacher’s role for these students then is simply to encourage them that if and when they come across material that seems to be at odds with what they know of our mesorah, they ought to return to our traditional sources first, before abandoning them. For they may well be surprised by what they find.

For other students, however, it is necessary to delve into specific examples of traditional texts that will serve to expand his or her conception of what is, and what might be, contained within our mesorah. We might point them to Rav Yosef’s statement in Kiddushin 30a that we are not experts on haserot vi-yeterot, or to Resh Lakish’s account in Masekhet Soferim (6:4) of three different versions of the Torah text that were found in the Temple courtyard and the decision Chazal made to follow the majority in cases of discrepancy between them. We might learn with them Rabbi Yehudah’s contention that Joshua, not Moses, authored the last eight pesukim of the Torah (Bava Batra 15a), Ibn Ezra’s expansion of this idea in his “secret of the twelve” that several other verses were written later as well (Deuteronomy 1:2), or Rav Yehuda ha-Chasid’s far more controversial suggestion that whole sections of the Torah were removed from and inserted into other books of Tanakh (Genesis 48:22, Numbers 22:17). We might show them the passage in Avot de-Rabbi Natan (34) that ascribes authorship of the dots found on top of certain words in our Torah text to Ezra, who used them to note his uncertainty as to whether those words belonged in our text or not, or the passage in Midrash Tanhuma (Exodus 15:7) that lists eighteen “tikkunei soferim” made by Anshei Keneset ha-Gedolah, suggesting that later scribes made minor emendations to the text of the Torah. Jumping to the modern period, we can point them to Rabbi Akiva Eger’s well-known list (Shabbat 55b) of all the pesukim quoted in the Gemara whose text differs from that in our humashim today; or to Netziv’s assertion that Kings David and Solomon were not the authors of Psalms and Song of Songs, respectively, but redactors of pre-existent texts that had come down to them from multiple authors and multiple eras (Introduction to Meitiv Shir); or to Rav Kook’s statement (Eder ha-Yakar pp. 42-43) that “anything that found a place in the nations of the world prior to the giving of the Torah, as long as it had a moral foundation and could be elevated to an eternal moral height, was retained in God’s Torah.”

As noted earlier, for many students these texts will only serve to heighten their confusion and make them less sure of what they can or should believe. But for others, just knowing that they exist can serve as the life preserver that keeps them tethered to our tradition as they navigate the choppy waters of academic Bible study. Therefore, unlike the previous steps, a school may want to consider presenting these texts only to those students who have demonstrated the capacity for nuance, critical thinking, and even dissonance in other areas of their academic and spiritual lives.

Expansive as our mesorah is, it would be a mistake to adopt a literal understanding of Ben Bag Bag’s famous assertion that “all is contained within it” as the guiding principle for a sophisticated Modern Orthodox approach to Biblical Criticism. As noted at the outset, there are hypotheses, interpretations, and conclusions offered by the Academy that have no antecedents in traditional rabbinic interpretation and some that lay well outside the pale of what a Modern Orthodox Jew can justifiably believe. But his exhortation of “hafokh bah va-hafokh bah”―to turn our understanding of Torah over and to turn it over again―for there is a richness and depth there that we likely didn’t see the first or second time, is invaluable advice that we ought to share with and impress upon our students. When armed with an appreciation of the value of critical scholarship, a recognition of its inherent biases, an understanding of the margin for error, and a deep seated commitment to return to our traditional texts rather than abandon them―an engagement with Biblical Criticism can serve to strengthen, broaden, and deepen our students’ understanding and connection to our Torah, and thus, by extension, enhance and enrich our community as a whole.

1 Gil S. Perl, “Engaging the Past, Sustaining the Future,” in Teaching Toward Tomorrow: Setting an Agenda for Modern Orthodox Education, ed. Yoel Finkleman (Jerusalem: ATID Publishing, 2008).

2 It is important to note that “Religious Truth” is noticeably absent from this scale, not because it doesn’t exist, but because I believe it to be fundamentally different from empirical truths. See Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’s excellent treatment of the issue in The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning (New York: Schocken Books, 2011).

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.