Jeffrey Saks

Having married Tonya Lewitt in 1931, the young Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, his wife, and newly-born daughter left Berlin where he had been studying since 1926. In immigrating to the United States he was following in the footsteps of his father, Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, who had been the Rosh Yeshiva of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary since 1929.

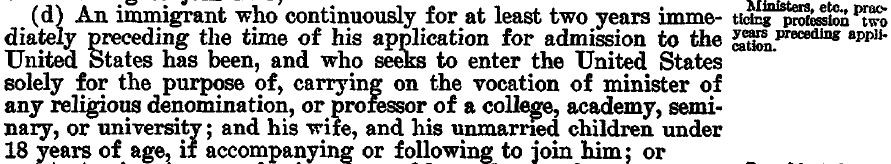

During a period of restrictive immigration to America, following the Immigration Act of 1924 which limited the number of immigrants in the name of preserving American racial homogeneity, and which especially curtailed immigration from countries with significant Jewish populations, the younger Soloveitchiks were able to enter under an exception for a “minister of any religious denomination” and seminary professors. To qualify for such a visa the Rav had to show he would be employed in his vocation, and through the Agudath Ha-Rabbonim, the Union of Orthodox Rabbis, presumably at the urging of Rav Moshe, Chicago’s Hebrew Theological College extended a job offer to Rabbi Yosef Baer.

1924 US Immigration Act of 1924 (Sec. 4d).

1924 US Immigration Act of 1924 (Sec. 4d).

Setting sail on the S.S. Baltic out of Liverpool, the Soloveitchiks departed on Saturday, August 20, 1932.

Manifest of “alien passengers” aboard S.S. Baltic sailing for New York, Aug. 20-29, 1932 (click for full image). Note that the Soloveitchiks’ baby daughter Atarah is mistakenly listed as “Sarah” for which there is a penciled correction “Atera.”

Manifest of “alien passengers” aboard S.S. Baltic sailing for New York, Aug. 20-29, 1932 (click for full image). Note that the Soloveitchiks’ baby daughter Atarah is mistakenly listed as “Sarah” for which there is a penciled correction “Atera.”  The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Monday afternoon, August 29, 1932, announcing the arrival of the S.S. Baltic that morning at 8:30 a.m. at the pier on West 19th Street in Manhattan (click for full image).

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Monday afternoon, August 29, 1932, announcing the arrival of the S.S. Baltic that morning at 8:30 a.m. at the pier on West 19th Street in Manhattan (click for full image).

The Rav’s daughter, Dr. Tovah Lichtenstein, informs us that after arriving in Liverpool, her parents and sister were guests of that city’s Rabbi, Isser Yehuda Unterman (who would later be elected Chief Rabbi of Israel). To avoid the associated halakhic problems with a sea voyage commencing on Saturday, they boarded the ship before Shabbat.

After a 9-day voyage, via Belfast, Glasgow, and Halifax, the Baltic docked at the West 19 Street Pier in Manhattan (today’s Chelsea Piers) on the morning of Monday, August 29, 1932.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Monday afternoon, August 29, 1932, detailing the Soloveitchiks’ arrival delay due to need for a “hearing on their status” at Ellis Island (click for full image). Note that the newspaper misreports the Rav’s age, and similarly errs in the daughter’s name (presumably basing their reporting on the ship manifest).

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Monday afternoon, August 29, 1932, detailing the Soloveitchiks’ arrival delay due to need for a “hearing on their status” at Ellis Island (click for full image). Note that the newspaper misreports the Rav’s age, and similarly errs in the daughter’s name (presumably basing their reporting on the ship manifest).

However, upon arrival in New York, instead of disembarking with the other passengers in Manhattan, the family was detained at Ellis Island “pending a hearing on their status.” A delegation of welcoming rabbis was left cooling their heels on the dock. It is unclear what the problem was that called their visa status into question, or if the rabbi and his family were merely the subjects of some measure of “extreme vetting.” Ultimately they were allowed entry without suffering too extreme a delay.

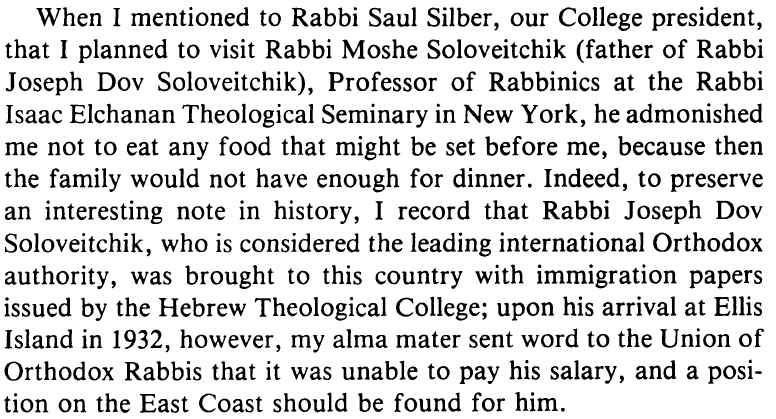

Oscar Z. Fasman, “After Fifty Years, an Optimist,” American Jewish History 69 (December 1979): 160.

Oscar Z. Fasman, “After Fifty Years, an Optimist,” American Jewish History 69 (December 1979): 160.

It is possible that the delay was caused by the fact that the Rav’s promised employer in Chicago had backed out of its offer. The long-serving rabbi and communal leader Oscar Z. Fasman recalled that, in light of the Great Depression, the Hebrew Theological Seminary was in fact unable to produce the salary, and cast the responsibility to provide a position for the Rav back on the Agudath Ha-Rabbonim in New York.

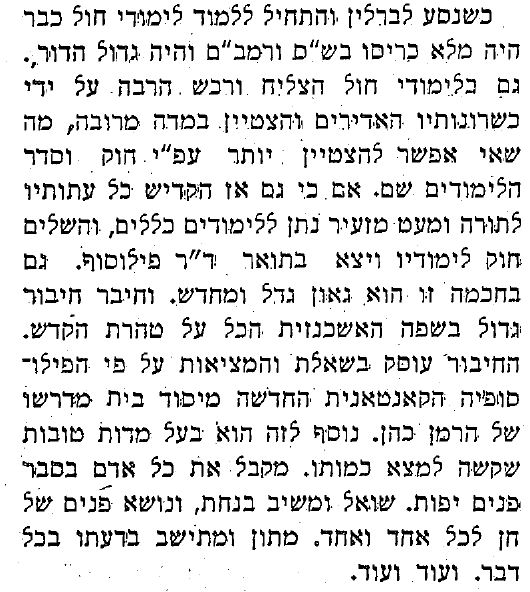

“When he travelled to Berlin and began his secular studies, his belly was already full with Shas and Rambam, and he was the greatest of his generation. Similarly, he succeeded in his secular studies and accomplished much through his phenomenal talents and greatly excelled, as much as can be achieved according to the academic standards there. However, even there he dedicated all of his time to Torah and just a bit did he give over to the general studies, completing his degree and graduating with a doctorate of philosophy. And even in this field he is a great genius and innovator (gaon gadol u-mechadesh). He composed a lengthy work in German—all within the parameters of holiness and sanctity.” Ha-Pardes 6 (October 1932): 5.

“When he travelled to Berlin and began his secular studies, his belly was already full with Shas and Rambam, and he was the greatest of his generation. Similarly, he succeeded in his secular studies and accomplished much through his phenomenal talents and greatly excelled, as much as can be achieved according to the academic standards there. However, even there he dedicated all of his time to Torah and just a bit did he give over to the general studies, completing his degree and graduating with a doctorate of philosophy. And even in this field he is a great genius and innovator (gaon gadol u-mechadesh). He composed a lengthy work in German—all within the parameters of holiness and sanctity.” Ha-Pardes 6 (October 1932): 5.

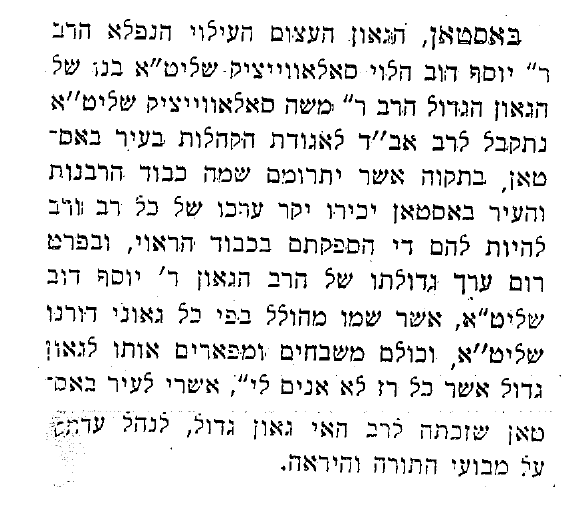

With his prospects for the future still murky, the Agudath Ha-Rabbonim held a reception to welcome the Rav to America at its executive committee session on October 10. That month’s issue of the American rabbinical journal Ha-Pardes reported on the session and on the Rav’s arrival in the most flowery praise for his genius, with tales of the illuy’s childhood brilliance at the knee of his grandfather, Rav Chaim Brisker. Interestingly, the anonymous article is not shy about mentioning the Rav’s academic career, but was quick to mention that pursuing a doctorate in neo-Kantian philosophy in Berlin in no way interfered with his full-time engagement in Torah study.

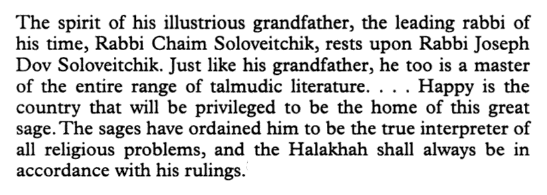

The article sounds completely authentic as the type of reportage of a rabbinic event of the time; it similarly reads like a notice that the newly-arrived young rabbi was open to any and all appropriate job offers! The article in Ha-Pardes concludes with the letter of approbation that was written for Rabbi Soloveitchik a year before his departure from Europe by the last Rav of Kovno, Avraham Duber Kahana Shapiro, which reads in part:

Translated in: Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (Ktav, 1999), vol. I, 25.

Translated in: Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (Ktav, 1999), vol. I, 25.

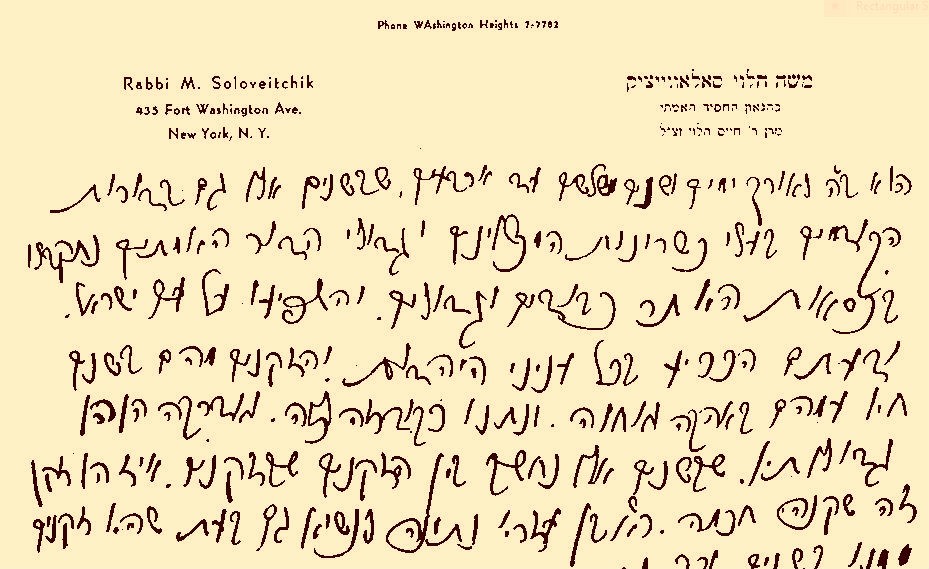

Three years later, in the summer of 1935, Rabbi Soloveitchik was a candidate to become the Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv. In connection with that campaign, Rav Moshe wrote a full-throated, exuberant letter of support of his son, addressed to the head of that city’s religious council. The letter was published by Manfred Lehmann in a festschrift published in honor of the Rav (co-published by Mossad HaRav Kook and Yeshiva University, 1984; text available online here and translated to English here).

A section from the concluding page of Rav Moshe Soloveitchik’s letter to the Tel Aviv Religious Council (19 Elul 5695/September 17, 1935) – click for full image.

A section from the concluding page of Rav Moshe Soloveitchik’s letter to the Tel Aviv Religious Council (19 Elul 5695/September 17, 1935) – click for full image.

Careful examination of Rav Moshe’s letter leads us to conclude that the anonymous 1932 Ha-Pardes essay was written by none other than the Rav’s father himself. The two texts share a remarkable amount of parallel content and language. Even bearing in mind that all rabbinic approbations and letters of support share a certain amount of boiler-plate verbiage, there can be little doubt that these two documents were the products of the same pen (click here for a side-by-side comparison). And this explains one of the noteworthy characteristics of the Ha-Pardes essay: In introducing the 29-year old new arrival to an American audience (in the hopes of generating offers of employment), amidst all of the praise heaped upon him, the one item the anonymous author omits is what would have been the customary rehearsal of the Rav’s yihus as the son and talmid muvhak of his father, Rav Moshe. The virtual absence of the father, among the premier rabbinical scholars in the United States at the time, can only be explained by the fact the he himself omitted it in his modesty! Had the journal’s editor penned the essay he surely would have included the deserved praise for Rav Moshe.

In fact, as the Rav’s sister reports, it was her father, Rav Moshe, whose “strong-mindedness and devotion” to his son Joseph Baer, resulted in a campaign to secure a respectable position. The most obvious venue would have been to hire the Rav at Yeshiva College, but Dr. Bernard Revel reluctantly rebuffed Rav Moshe’s entreaty, with the very real excuse that Yeshiva, too, was on the verge of bankruptcy. Yet, through Rav Moshe’s efforts, the Rav was invited to serve as Chief Rabbi of Boston. This offer was long-thought to have been presented by the Chevra Shas of Greater Boston, but as Seth Farber has shown, it was likely at the initiative of the newly founded Va’ad Ho’Ir under the leadership of Morris Feinberg. In all cases, the position involved the spiritual leadership of eleven conglomerated Orthodox synagogues. The next issue of Ha-Pardes reported:

“Boston—The great Gaon, spectacular illuy, HaRav R. Yosef Dov HaLevi Soloveitchik shlita, son of the great Gaon, Rav Moshe Soloveitchik shlita, has been accepted as the Rav Av Beit Din of the united congregations in the city of Boston, in the hopes that he will elevate the glory of the rabbinate there … Fortunate is the city of Boston to have merited this great Gaon to manage the holy affairs of this flock with Torah and piety.” Ha-Pardes 6 (November 1932): 4.

“Boston—The great Gaon, spectacular illuy, HaRav R. Yosef Dov HaLevi Soloveitchik shlita, son of the great Gaon, Rav Moshe Soloveitchik shlita, has been accepted as the Rav Av Beit Din of the united congregations in the city of Boston, in the hopes that he will elevate the glory of the rabbinate there … Fortunate is the city of Boston to have merited this great Gaon to manage the holy affairs of this flock with Torah and piety.” Ha-Pardes 6 (November 1932): 4.

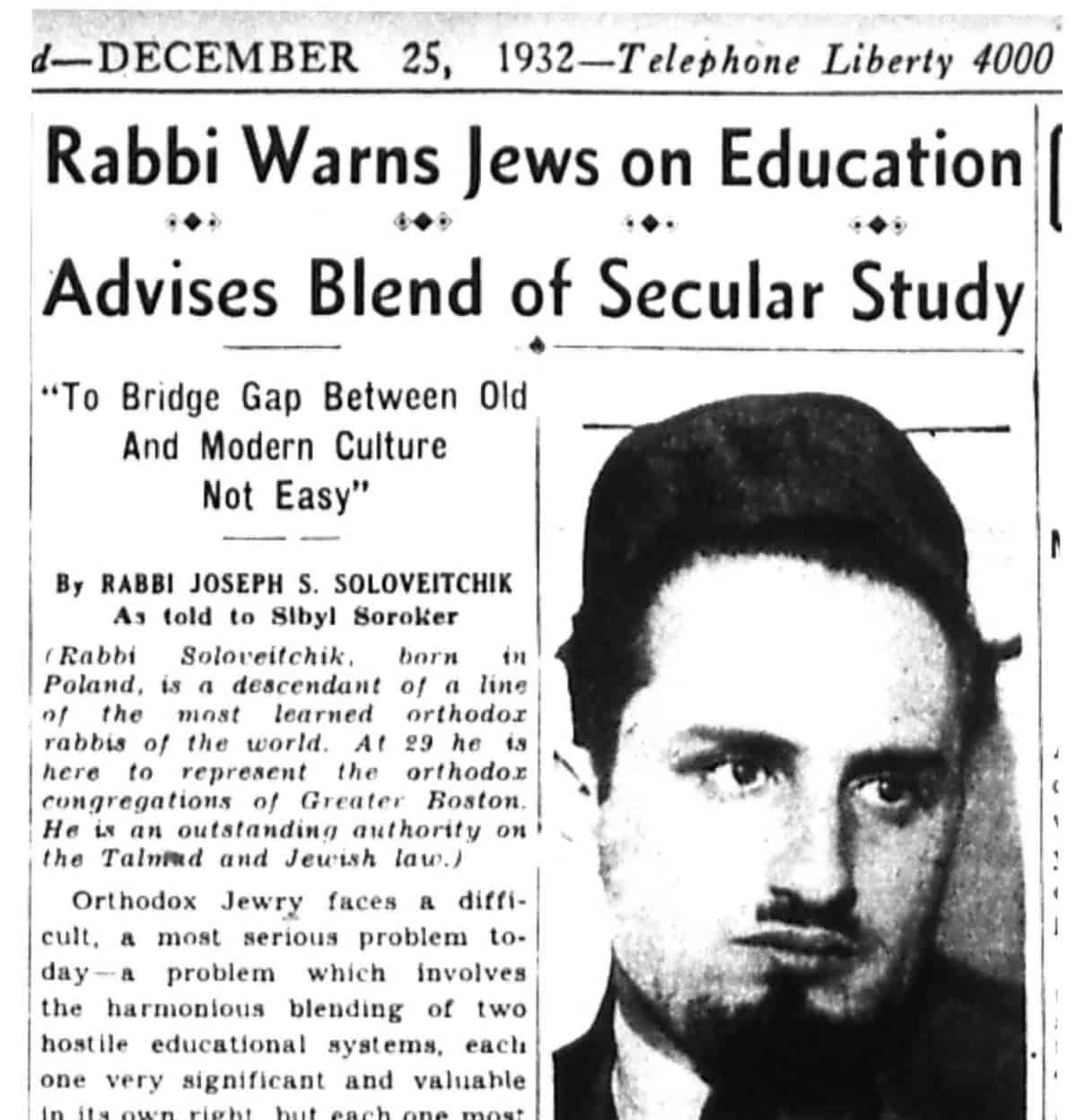

His arrival in Boston at the beginning of December 1932 actually coincided with the approval of his doctorate on the philosophy of Hermann Cohen by the faculty of Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. While he had completed all the requirements before departing Europe the previous summer, his degree was issued only on December 19. His official instillation as Chief Rabbi of Boston was attended by rabbinic luminaries such as R. Zev Gold, president of American Mizrachi, R. Meir Bar-Ilan of World Mizrachi, and others. From this platform he quickly began to set his focus on his high priority of rejuvenating Jewish education in the city, as evidenced by the December 25, 1932 interview in the Sunday Advertiser—recently unearthed by The Lehrhaus.

Sources

Special thanks to Yisrael Kashkin for his assistance in the preparation of this article.

Seth Farber. An American Orthodox Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Boston’s Maimonides School. Hanover: Brandeis University Press, 2004.

Yisrael Kashkin. The Rav: Resources on Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zt”l. Available at http://rabbisoloveitchik.blogspot.co.il.

Shulamith Soloveitchik Meiselman. The Soloveitchik Heritage: A Daughter’s Memoir. Hoboken: Ktav, 1995.

Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. Vol. I. Hoboken: Ktav, 1999.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.