Judah Kerbel

If there was one part of daily prayer that you would feel comfortable skipping, what part would that be? Many might wish to skip Tahanun. Anecdotally, however, it seems that korbanot, the daily recitation recounting the performance of sacrifices in the Beit Hamikdash, is popularly skipped either by individuals or entire congregations. When one comes to synagogue late, not only will they have to skip parts of Pesukei de-Zimra, but I would imagine that korbanot would be the least of our priorities.

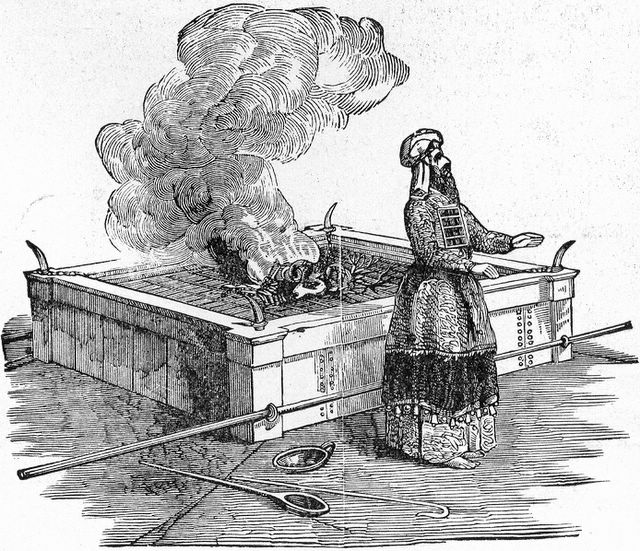

When we search for meaning in our daily prayers, it is easy to overlook that they harken back to the absence of the Beit Hamikdash, a void that we are always looking to fill. This connection to the Beit Hamikdash is particularly true of the korbanot section. However, not only do we often miss those connections as we go through the daily motions, but in many cases, korbanot are deemphasized if not completely omitted from the prayer routine.

Some synagogues, after completing the blessing of mekadesh et shimkha ba-rabim, go directly to the baraita at the end of korbanot, the thirteen hermeneutical principles of Rabbi Yishmael. Even in synagogues where enough time is left to say korbanot, many opt not to say some or most of them.

In this piece, I want to explore the halakhic role of various passages related to the sacrifices and their significance. By the end, I hope to have conveyed the importance of reciting these passages and their spiritual relevance.

Which parts of korbanot are halakhically required?

Two passages in the Talmud describe the virtue of reciting korbanot on a daily basis. One reports an emotional discussion between Abraham and God. While Abraham famously pleaded with God to not destroy Sodom if there were more than ten righteous individuals, he also argues on behalf of the Jewish people in a couple of places in the Talmud. In Taanit 27b:

Abraham said: Master of the Universe, perhaps the Jews will sin before You. Will You treat them as You did the generation of the flood and the generation of the dispersion, and destroy them? God said to him: No. Abraham said before God: Master of the Universe, tell me, with what shall I inherit it? How can my descendants ensure that You will maintain the world? God said to Abraham: “Take for Me a three-year-old heifer, and a three-year-old goat, and a three-year-old ram, and a turtledove, and a young pigeon” (Genesis 15:9). God was alluding to the offerings, in whose merit the Jewish people, and through them the entire world, will be spared divine punishment.

Abraham said before God: Master of the Universe, this works out well when the Temple is standing, but when the Temple is not standing, what will become of them? God said to him: I have already enacted for them the order of offerings. When they read them before Me, I will ascribe them credit as though they had sacrificed them before Me and I will pardon them for all their transgressions. Since the offerings ensure the continued existence of the Jewish people and the rest of the world, the act of Creation is read in their honor.

While this passage does not indicate a requirement to recite passages related to korbanot, we can understand the tremendous importance of doing so. While sacrifices were brought for a variety of reasons, a crucial purpose in bringing sacrifices was the atonement of the individual or the Jewish people at large. As Ramban famously writes in his commentary to Leviticus, when a human being sins, he or she really owes their own blood to God; however, God spares us and asks us to sacrifice animals in our place (Leviticus 1:9). If that is so, how do we achieve that level of atonement in the absence of the Beit Hamikdash? It turns out that God always had a contingency plan: our very learning and articulating the rite of the sacrifices constitutes their being offered.

This is, of course, echoed by the prophetic verse, “Instead of bulls, we will pay [the offering of] our lips” (Hosea 14:3).

Even though the recitation of sacrifices substitutes for their offering, it is not as important to recite them as it would be to bring them in the Beit Hamikdash if we were able. Nevertheless, post-Talmudic halakhic authorities codify the importance of this recitation.

Tur and Shulhan Arukh discuss the recitation of korbanot in three different sections: Siman 1:5-9, Siman 48, and Siman 50. In Siman 1:5, they state that it is “good” to recite the passages of the olah (Leviticus 1:1-9), minhah (Leviticus 2:1-13), shelamim (Leviticus 3:1-5), hatat (Leviticus 4:27-31), and asham (Leviticus 7:1-5). They stipulate that these passages should only be recited during the day. They state that one should say after these passages that this recital should be as if we ourselves offered these sacrifices. One should then recite the verse “It shall be slaughtered before the LORD on the north side of the altar, and Aaron’s sons, the priests, shall dash its blood against all sides of the altar” (Leviticus 1:11). This verse invokes the memory of the Binding of Isaac. Finally, “some people have the practice” to recite the passage related to the basin, the terumat ha-deshen, the Tamid sacrifice, and the incense. With all of this said, there seems to be no requirement to recite these passages, only that it is “good” to do so or that “some people have the practice” to do so. It is noteworthy that most of the passages mentioned in 1:5 are not included at all in contemporary siddurim. Arukh Hashulhan (OC 1:24) explains that these passages correspond with public sacrifices, and since there is no purpose in their recitation by individuals, they are not canonized in the siddur. He simply says “there is no need” to recite them and clarifies that Tur only brings it as a custom.

However, in Siman 48, Tur writes that “they established” to recite the passage delineating the Tamid sacrifice (Numbers 28:1-8), which suggests a stronger requirement. Although it is not clear who “they” is, Beit Yosef says the recitation is based on the Gemara in Taanit cited above. Rema in Shulhan Arukh also writes that the passage of the Tamid is recited. Mehaber is not as explicit, but he clearly assumes its recitation, based on his comment that the passage of the Musaf sacrifice is recited after the recitation of the Tamid. Similar to what Beit Yosef says, Mishnah Berurah explains the requirement to say the Tamid is that its recitation serves as a substitute for the sacrifices. Because sacrifices are offered while standing, the commentaries on Shulhan Arukh (including Magen Avraham, Ba’er Heitev, and Mishnah Berurah) say that the Tamid should be recited while standing, furthering the idea that the recitation of the Tamid is a substitute for its being offered (although Sha’arei Teshuvah and Arukh Hashulhan reject this requirement). Additionally, both Sha’arei Teshuvah and Mishnah Berurah stipulate that the Tamid is to be recited aloud in the synagogue because the sacrifice is a communal sacrifice.

The recitation of sacrifices is further mentioned in Siman 50 of Tur and Shulhan Arukh. Here, there are three passages that are stipulated to be recited: Tamid, Eizehu Mekoman (the fifth chapter of Mishnayot in Masekhet Zevahim), and Rabbi Yishmael Omer. There is a twofold purpose in reciting these passages in particular: one is to replace the performance of sacrifices with their recitation, as discussed. The other is based on one’s daily requirement to learn Torah. The Gemara (Kiddushin 30a) says that one should devote a third of their life to learning Scripture, a third to learning “Mishnah” (i.e. adjudicated laws), and the final third to “Talmud” (i.e., interpretation of the law). Given that obviously one does not know how long they will live and therefore cannot preemptively divide their time in this fashion, the Gemara clarifies that each daily regimen of learning should be divided into these three sections. Based on this, Ba’alei Ha-Tosafot explain, based on the siddur of Rav Amram Gaon, that we accomplish this daily regimen through the recital of the three aforementioned passages of the Tamid (Scripture), Eizehu Mekoman (Mishnah), and Rabbi Yishmael Omer (Talmud). Eizehu Mekoman is the set of mishnayot chosen to be recited because it is the only chapter of Mishnah that does not (explicitly) contain any disputes among the Sages; based on this, Vilna Gaon these mishnayot are halakhah le-moshe mi-Sinai. Furthermore, Tur cites the Gemara in Menahot (110a) that cites this verse from Malakhi (1:11): “And in every place offerings are presented to My name.” The Gemara wonders, are offerings brought literally everywhere in the world? They cannot be offered outside the Beit Hamikdash! Rabbi Yonatan suggests that the verse refers to those who study the laws of offerings, and it is considered as if they are making offerings, no matter where their study takes place. While Rabbi Yishmael Omer does not directly deal with sacrifices, it appears at the beginning of the midrash Sifra/Torat Kohanim on the Book of Leviticus. Thus, it precedes the midrashic-halakhic discussion of sacrifices and simultaneously provides the tools for deriving rabbinic law from Scripture (Arukh Hashulhan OC 50:1).

Practically, so far, it seems that the Tamid is the most essential passage for recitation, while Eizehu Mekoman and Rabbi Yishmael Omer are normative to recite as well. Importantly, R. Shalom Yosef Elyashiv and R. Eliezer Melamed (Peninei Halakhah, Hilkhot Tefillah, 13:1) both maintain that saying the Tamid passage takes precedence over many parts of Pesukei de-Zimra. Leviticus 1:11, as mentioned above, is normatively recited with the Tamid.

With that said, Tur also mentions the recitation of a passage of Gemara in Yoma (33a) that lists the order of the daily Temple service. Mehaber does not mention this, but Rema suggests that there are “some” who say this. The advantage of saying this passage is that it engages one with the entire day of service in the Beit Hamikdash.

As mentioned before, recitation of the passage describing the incense, ketoret, is mentioned as customary in the first siman of Tur and Shulhan Arukh. This passage received extra attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, as there is a long tradition of the incense serving a protective role during a plague or epidemic. With that said, Arukh Hashulhan (OC 50:1) assumes its normative recitation along with the Tamid. R. Eliezer Melamed, based on the Zohar (Vayakhel 219a), places the recital of Ketoret on a high pedestal, and like with the Tamid, it would take precedence over other parts of Pesukei de-Zimra. While the Tamid, as a sacrifice of flesh and blood, connects us with God regarding our material existence, the Ketoret is a more spiritual offering. Thus, the Tamid and Ketoret complement each other (Peninei Halakhah, 13:6).

While the recital of Ketoret and Eizehu Mekoman are highly praiseworthy, poskim point out that their value—both in terms of their function as Torah learning and in terms of their substitution for sacrifices—assumes that one understands the passages. Interestingly, and perhaps ironically, talmidei hakhamim, Torah scholars, may be exempt from saying korbanot. This is because that time could be spent on more in-depth learning (see Mishnah Berurah 1:12, 1:17). R. Aryeh Zev Ginzberg, in Divrei Hakhamim (pp. 32-33, question #48), discussed this exemption with numerous poskim, who clarified that this applies to any talmid hakham, whether or not they generally learn all day. Still, they maintain that everyone should say the passage of the Tamid.

It does not appear that the passage related to the basin (Kiyor) is considered mandatory by poskim. However, Berakhot (14b-15a) says that “one who wants to completely accept upon himself the yoke of Heaven should [after arising] relieve himself, wash his hands, put on tefillin, recite Shema, and pray [the Amidah], and this is considered complete acceptance of the yoke of Heaven.” Thus, it is not a stretch to say that we are mirroring the handwashing of the priests before engaging in their service when we wash our hands before our service, which is prayer. Thus, while not technically required, there would seem to be a meaningful virtue in reciting the passage about the Kiyor.

Women and Recitation of Korbanot

The codes do not explicitly delineate the requirement for women to recite korbanot, including the Tamid. On the one hand, women surely have a relationship with korbanot and would bring them in the time of the Beit Hamikdash. Furthermore, according to poskim who maintain that women are required to pray Shaharit, women should be required to recite the Tamid passage as well. Thus, Beit Yosef in Siman 47 cites Agur (R. Jacob Landau) as requiring women to recite the blessing for learning Torah because women should be reciting the Tamid passage. This assumes that since women receive equal benefit from the Tamid sacrifice, the obligation to recite the passage is equal (see Hida, Yosef Ometz, Siman 67). On the other hand, R. Eliezer Melamed (Peninei Halakhah, Women’s Prayer, 15:1) asserts that the common practice is that women are not required to recite korbanot, including the Tamid passage. The reason for this is that the obligation for women to pray is unrelated to the relationship between prayer and the Tamid sacrifice, and it instead relies on a more basic need for Divine compassion. Furthermore, women do not give toward the mahatzit ha-shekel, which funds communal sacrifices. However, R. Melamed notes that a woman who wishes to recite the Tamid is to be commended.

Evaluating the Impact of Sacrifice on Prayer

The inclusion of passages relating to sacrifices in prayer is not incidental. It is not that one should theoretically say these passages, and therefore they are included in prayer. Rather, sacrifices and prayer have a dependent relationship. They are both avodah. Priests in the Torah are identified as servants of God.[1] Likewise, when the Torah commands us “to love the Lord your God and serve God with all your heart and all your soul” (Deuteronomy 11:13), “what is service of the heart? It refers to prayer” (Taanit 2a). Prayer and sacrifice are both service to God.

The Talmud also debates whether prayer (particularly the Shemoneh Esrei) originates from the Patriarchs or from the daily Tamid sacrifice (Berakhot 26b). It concludes that the concept of praying three times a day originates with the Patriarchs, but many aspects of the sacrificial rite are reflected in prayer, such as the fact that the morning prayers can only be recited until the latest time that the Tamid was offered in the Temple. Many aspects of behavior during Shemoneh Esrei correspond with requirements related to sacrifices, such as the requirement to recite it standing, to have a fixed spot, and to wear appropriate clothing (Shulhan Arukh OC 98:4).

Finally, it is not just the Amidah that corresponds specifically with the Tamid sacrifice, but the entire structure of the prayer book is said to correspond with the structure of the Beit Hamikdash. Thus, early blessings correspond with the Ezrat Nashim, the outer part of the Mikdash; fifteen steps leading from Ezrat Nashim to Ezrat Yisrael correspond with the fifteen Birkot Hashahar; the blessing mekadesh et shimkha ba-rabim corresponds with the Gate of Nikanor; Birkat Kohanim corresponds with the Ezrat Kohanim; the Altar corresponds with the recitation of sacrifices; the antechamber to the Sanctuary (Heikhal) corresponds with Pesukei de-Zimra; the Heikhal corresponds with the blessings of Shema—the Menorah with the first blessings, the incense altar with the recitation of Shema; the Parokhet with the last blessing; and the Holy of Holies corresponds with the Amidah.[2]

Yom Kippur

With Yom Kippur approaching soon, it is worth noting the significance of sacrifices during this period. According to a baraita brought in Masekhet Yoma (39a), one of the early signs of the imminent destruction of the Holy Temple was the cessation of some aspects of the Yom Kippur sacrificial service that signified atonement. The absence of the Beit Hamikdash is acutely felt on Yom Kippur. The Avodah portion of Musaf is meant to provide an opportunity to both learn about the service that took place but to also serve as a substitute for the service that cannot be done. The hazzan, serving as a substitute for the High Priest, recites that which the High Priest would say in asking God for atonement on behalf of the Jewish people. The jubilant singing of Mareh Kohen is meant to mirror the happiness the people experienced when the High Priest emerged from the Holy of Holies successfully. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik describes the way in which his father and grandfather would say the Avodah:

They said it with so much enthusiasm, such ecstasy, that they could not stop. They were no longer in Warsaw or Brisk; they were transported to a different reality … One who recites the piyyutim of the Avodah is placed in an almost beatific trance as he both observes and becomes involved in the ritual as it unfolds, compelled to follow every detail until its successful completion.[3]

However, right after the euphoria of Mareh Kohen, we immediately begin to recite poetry that mourns our inability to experience this service in its actual form. In Rabbi Soloveitchik’s words:

Suddenly, the payettan and the reader of the piyyut are rudely awakened from a dream. They cry, “This is no longer the reality in which we live. It existed once, yes, but is no more” … Fortunate is the eye—but not our eyes.[4]

Not only are there tears about the state of exile, but Rabbi Soloveitchik goes as far as to say that after this point in the prayers, Yom Kippur is transformed into a kind of Tishah Be-Av with its attendant mourning of the Beit Hamikdash. He notes that Tishah Be-Av and Yom Kippur are connected because ongoing sin prevents the rebuilding of the Beit Hamikdash. In fact, after Mareh Khohen, the level of joy found in many of the piyyutim in Shaharit and earlier in Musaf ceases for the rest of Yom Kippur.

If our atonement is especially dependent on the sacrificial rites of Yom Kippur, what are we to do without it? That brings us back to where we began. Prayer substitutes for sacrifice every day, but this point is accentuated most on Yom Kippur. To this day, I remember my rabbi in college pleading with us to read the Avodah in English instead of Hebrew so that we would understand it. The Avodah on Yom Kippur should not just be recited but should be understood and internalized as representing the hopes and dreams of the Jewish people for the coming year.

Conclusion

It is clear, then, that recitation of sacrifices is intrinsically connected with and relevant to prayer. The Beit Hamikdash, our experience of the holiest place on earth, where the Divine meets our world, is no more. But through invoking sacrifices, we maintain our connection. Reciting the Tamid in particular not only recalls the relationship between prayer and sacrifice, but it also defines the entire basis for prayer. To omit this passage is to omit the role that sacrifice is meant to play in the Jewish spiritual life and the daily method of atonement granted to us. Including this passage demonstrates a deep appreciation for the gift God gave us in being able to pray despite the destruction of Beit Hamikdash and our exile from the Divine presence. We fully encapsulate the meaning of prayer through inclusion of korbanot.

With that said, it is clear that not all of the sacrificial passages included in the siddur are halakhically mandatory. Should synagogues return to their recitation? On the one hand, saying all of the sacrifices is time consuming, and weekday prayer services, especially those that cater to working individuals, are under time pressure. Indeed, there are times in which we validate longstanding synagogue customs that are not entirely contrary to Halakhah, even if there may be a better halakhic path.[5] Furthermore, saying just the Tamid passage (and perhaps Eizehu Mekoman) can be confusing, as it would require skipping pages and jumping around. Even though we jump around the siddur a little before Pesukei de-Zimrah in general, adding more of the same may not be entirely user-friendly.

On the other hand, it is worth reevaluating the opportunity to include the Korban Tamid in our prayer services, and perhaps synagogues can find a way to either recite it aloud or allow time for its recitation before Rabbi Yishmael Omer.

One final note regarding the opportunity to recite sacrificial passages in our prayer: Despite Korah’s claim that Moses and Aaron seized all of the opportunities for holiness, the Jewish people is a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6). Each Jew possesses an element of priesthood. The inclusion of tekhelet in the tallit for men is an opportunity to embody a small aspect of priestly clothing. Likewise, while the physical work in Beit Hamikdash could only be done by the High Priest, each one of us can have a portion of this role through reciting the sacrifices. In the words of Rabbi Asher Lopatin:

The bulk of Korbanot—and the reason it gets its name—aims to convince us that we are not just plebes and nobodies, but that every one of us can become a High Priest offering the holy tasks performed daily in the ancient Temple. By the time we are done, we have cleaned the altar, washed our hands with the holy waters of the Temple laver, and offered all the daily sacrifices: animal and vegetarian (incense) offerings, voluntary offerings, sin offerings, Passover offerings. A full day’s work … For a few minutes, while you are saying Korbanot, you are critical to the success of an elaborate system of holiness that takes up a quarter of the Torah.

May it be God’s will that, despite the lack of the Beit Hamikdash, that the prayer of our lips will be worthy of acceptance and considered as if we ourselves offered the Sacrifices, bringing favor to the entire Jewish people.

[1] In many cases, priests’ service of God uses the root sh-r-t, but in Exodus 30:16, the half shekel is given toward avodat ohel mo’ed, the service of the Mishkan. It is noteworthy that this avodah is meant to provide atonement.

[2] See R. Shimon Schwab’s Rav Schwab on Prayer (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2001), xxx-xxxiii for greater elaboration on this point.

[3] Dr. Arnold Lustiger and R. Michael Taubes, eds., Yom Kippur Machzor with Commentary Adapted from the Teachings of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (New York: K’hal Publishing, 2006), 618-619.

[4] Ibid., 620.

[5] For an example related to the High Holiday season, see Mahzor Vitry Siman 325, in which the author cites Rabbeinu Tam’s justifications for including piyyutim in the blessings of Keriat Shema, even though it could be seen as an impermissible interruption. He ends with the statement “minhag halakhah hi”—minhag is equivalent to Halakhah.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.