Avi Garson

To engage thinking Jews living in the modern world, we must promote a vibrant Judaism firmly rooted in tradition but in tune with reality. A Judaism deeply connected with its identity and history, but receptive to new ideas. A Judaism that is tolerant, non-sectarian, and innovative, while remaining unconditionally committed to the framework of halakhah; intellectually sophisticated and sensible, but spiritually demanding and religiously inspiring; rigorous and substantive, but with room for music and emotions.

While many readers may not associate the above with contemporary Sephardic Judaism, these are, essentially, the core principles at the foundation of the classical Sephardic approach that underpin its entire ethos and vision. By classical, I mean the original Sephardic tradition of the Golden Age of Spain and those who strived to maintain that legacy and approach to Jewish life ever since. Sephardic Jewry has struggled to preserve its own intellectual heritage, which has resulted in this holistic outlook and deep well of tradition to slowly be overlooked and somewhat forgotten. It is time to reclaim the Sephardic tradition and remind ourselves and the wider Jewish community that being Sepharadi is not only about Mimouna and hilulot, fez hats, and henna at weddings, what goes inside the bourekas, jachnun, and kibbes, and our Pesah rice-eating habits – as important as they are. The aesthetics are trivial without the spirit that animates the tradition. It is time for Sephardic thought, with its rich literary and scholarly legacy and compelling worldview, to return to the forefront of Jewish public discourse.

Before tracing the historical roots of Sephardic Judaism and delving into key features of this approach to Jewish life and its challenges, I will begin by relaying my own experience, which illustrates, on a small scale, what has happened in many places around the world and why it is in great need of revitalization.

Gibraltar: A Microcosm Reflecting a Larger Trend in Sephardic Judaism

Gibraltar is a miniscule British overseas territory that lies at the southernmost tip of the Iberian Peninsula opposite the coast of Morocco, guarding the western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. Geographically, one could say that Gibraltar is situated in the nexus of the Sephardic heartland.

I feel privileged to have grown up in this tiny but unique city, with its rich history and fascinating stories. Despite numbering fewer than one thousand Jews, it is a robust and well -organized community boasting more Jewish institutions than many cities around the world with far larger Jewish populations. It has four active synagogues, Jewish primary and secondary schools, several kosher shops and restaurants, a kollel, and a host of other communal facilities. It prides itself on being a Sephardic community, and this is most ostensible in its well preserved tunes, minhagim (local customs), and tasty cuisine.

Although it has managed to maintain its precious synagogue liturgy, beautiful melodies, careful pronunciation, and centuries-old family adafina recipes, a gradual process of Ashkenazi “Haredization” has somewhat diluted the community’s traditional Sephardic character. As a result, and most probably its cause too, the majority of Gibraltarian youth attend Ashkenazi yeshivot after high school. Many, including myself, were and still are encouraged to go to Gateshead Yeshiva – modeled on the famed Novardok chain of yeshivot that were once scattered across the Russian Empire – and many will typically end up in the Mirrer Yeshiva in Israel or other satellite yeshivot of that haredi persuasion.

Naturally, this has led to the adoption of certain ideas, values, norms, and even dress codes not indigenous to Sephardic Jewry, and this development has in turn resulted in the inevitable decline of Sephardic culture, awareness, and learning. I share my personal experience because this unconscious transformation is hardly unique to little Gibraltar; this process of acculturation has been transpiring in most Sephardic communities around the world over the last fifty years, rapidly accelerating in the last twenty years or so. It is a familiar story that will, undoubtedly, resonate with many readers.[1]

Now, some readers may wonder what exactly is the Sephardic tradition, if not its cultural expressions and colorful customs. Many self-identifying Sephardic Jews may relate the Sephardic with the mimetic practices they witnessed their grandparents transmitting, and this is certainly an integral part of the Sephardic experience. There is, however, an ideological dimension and mindset that has been largely neglected outside the confines of academia. This intellectual contribution is the most brilliant yet underappreciated component of our heritage. I discovered this body of thought through the writings and lectures of certain rabbis and academics who have taken it upon themselves to preserve and carry that flickering torch, such as the late Hakham Prof. José Faur, the late R. Dr. Abraham Levy, R. Dr. Marc Angel, R. Joseph Dweck, and Prof. Zvi Zohar, to name a few of these custodians. To better appreciate the Sephardic intellectual tradition, we will put its remarkable journey in historical perspective.

A Brief History of the Origins of Sephardic Jewry

Sephardic Jews have their roots in Babylon, the wider Levant, and the lands surrounding the Mediterranean, but the Sephardic identity truly took shape in Spain. Jews began to settle in the Iberian Peninsula in Roman times, and they continued to live in the region during the Visigothic Kingdom (fifth-eighth centuries) where they faced periods of persecution and restrictive laws. During Islamic rule (eighth-twelfth centuries), however, Jewish settlement in what was called Al-Andalus expanded significantly. The situation for the Jews began to gradually deteriorate with the Christian Reconquest, culminating in the Inquisition and the damning Alhambra Decree issued by the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, which marked the end of any visible Jewish presence in Spain for five hundred years.

From the outset, it is necessary to stress the obvious fact that Sephardic Judaism is not monochromatic and Sephardic Jews are not a monolith. Each community has its own story, set of differences, and cherished variations that they hold dear. Indeed, following the Spanish expulsion in 1492, the Jews scattered across the globe; those who settled in Amsterdam, London, Hamburg, Italy, and the New World, came to be known as Western Sephardic Jews. These Jews have undergone a greater degree of European influence compared to other Sephardic societies. A very large proportion of exiles fled to North Africa and established thriving Sephardic communities across the Ottoman Empire, the Middle East, and beyond. Nonetheless, despite the geographical and cultural diversity of the Sephardic diaspora, there are still certain fundamental commonalities that stem from their shared origins in Sefarad (Spain).

Many of these foundational ideas and cultural values have been passed down through the biological and, oftentimes, ideological descendants of these Spanish Jews. The latter includes many Maghrebi and Middle Eastern communities (now commonly referred to, Eurocentrically, as Mizrahi) as well as Yemenite, Persian, Italian, and Indian Jews. Although their ancestors may not have directly descended from Spain, they absorbed essential aspects of the classical Sephardic tradition such as its liturgy, legal codes, and philosophical teachings. The Spanish identity and culture became so dominant that in many instances the Toshavim, or Musta’arab Jews, who predated the newly arrived Spanish refugee communities, even adopted Ladino and other imported customs. Thus, these non-Ashkenazic communities also came to be known, and began to identify, as Sephardic ones.[2]

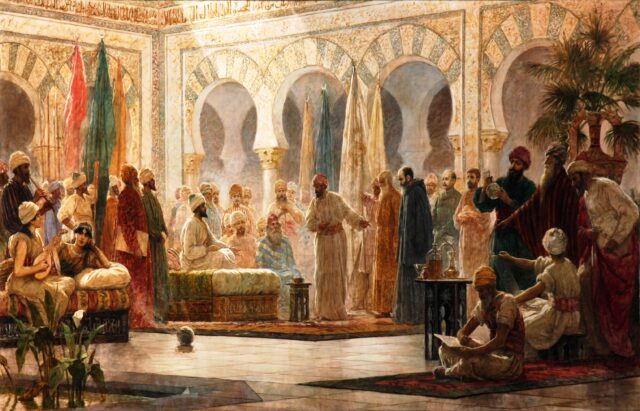

The “Sephardic” approach to life that cultivated in Babylon, matured in North Africa, and fully developed in Al-Andalus, is best exemplified by the Andalusian model during the Islamic Golden Age, which flourished from the ninth to about the twelfth centuries. The Andalusian Jews not only harmonized their worldly pursuits with their religious lives, but they played an integral role in the cultural tapestry of Iberian society, occupying influential positions and actively contributing to the intellectual and economic landscape of Al-Andalus.

In this period, Jews were immersed in medicine, philosophy, poetry, philology, astronomy, music, trade, statecraft, and even military activity. Simultaneously, they produced groundbreaking works of Jewish thought, law, ethics, Talmudic commentaries, and Hebrew grammar. The likes of Hasdai ibn Shaprut, Jonah ibn Janah, Menahem ben Saruq, Dunash ben Labrat, Shemuel Ha-Nagid, Shelomo Ibn Gabirol, Bahya Ibn Paquda, Yehudah Ha-Levi, the Ibn Ezra and Ibn Tibbon families, and of course, Maimonides, saw no inherent contradiction between these two endeavors.

Even after the Golden Age, wherever Sephardic Jews settled, they continued to engage with wider society, be it commercially, politically, intellectually, or culturally. A by-product of this integrationist attitude is that Sephardim were largely proud and active contributing citizens of their host countries. This attitude often coexisted with a love of Eretz Yisrael. This dual love manifests most prominently in the piyyutim and poetry of the Judeo-Andalusian poets whose admiration of Spain harmoniously intertwined with their deep yearning for the Promised Land. [3]

The Sephardic Worldview

This rich history has yielded a distinctive and venerable intellectual heritage. The Maimonidean middle-path of moderation and timeless principle of “accepting the truth regardless of its source”[4] are inextricably linked and form an integral part of the DNA of the Sephardic tradition. These notions stand in sharp contrast to the outlook embodied by the slogan hadash asur min ha-Torah (“innovation is biblically forbidden”) most famously championed by Rabbi Moses Schreiber [Hatam Sofer] (1762–1839), a teaching that is entirely unfamiliar to the Sephardic mind.[5]

Broadly speaking, the classical Sephardic approach is faithful to tradition and Torah but not petrified by modernity. It remains loyal to halakhah but imbues it with a spirit of tolerance, inclusivity, and compassion.[6] Halakhah evolves, but it does so organically and gently through a set legal framework rather than being swept away by social trends. So, while halakhic creativity and innovation are indispensable,[7] radical reform is unprecedented and deemed completely unviable.[8]

It is common for Sephardic poskim (legal scholars) to champion the Talmudic principle ko’ah de-heteira adif (“the ability to permit is preferable”) and to utilize meta-halakhic notions that lean towards leniency, such as derakheha darkhei no’am (“its ways are ways of pleasantness”) and ha’alamat ayin (“turning a blind eye” in cases where insistence upon complete fulfilment could lead, in practice, to their complete violation) as guiding principles to their interpretation and application of halakhah.[9]

In the absence of a Sanhedrin, there are, of course, limitations to post-Talmudic rabbinic authority. The reestablishment of a Sanhedrin would theoretically grant the ability for rabbis to resolve many fundamental societal issues. According to Maimonides, the reinstitution of a Sanhedrin does not require a supernatural intervention but rather merely sufficient rabbinic will and consensus – perhaps the ultimate miracle.[10]

In the spirit of Maimonides’ philosophy of moderation, the Sephardic posek tends to eschew humrot (additional strictures), avoid imposing stringencies on the kahal (community), and publicize the ikar ha-din (fundamental law) as the halakhah. As Rabbi Yosef Messas writes, “We the Sephardim walk through the Valley of ‘Equilibrium,’ which is the the Valley of the King who rules the world, Blessed be He, prohibiting only that which is prohibited, permitting that which is permitted, and only adding a few humrot on certain well known matters and without creating additional fences around the baseline halakhah.”[11]

Another major part of the classical Sephardic tradition is the general stance towards the Written and Oral Laws, which is shaped by its Ge’onic-Andalusian rationalist tendencies, and differs quite starkly with other traditions that espoused a more literalist and rigid interpretation. Many of the Ge’onim and Sages of Old Sepharad did not interpret the entire biblical narrative at face value because the Torah is neither a scientific textbook nor a historical treatise, but rather, primarily, Israel’s law and constitution embedded within a national narrative and collective memory.[12]

Consequently, certain phrases or stories found within Tanakh are viewed as allegorical and interpreted figuratively.[13] Similarly, the many fantastical anecdotes and bizarre statements one finds in the Talmud need not be accepted uncritically. These hakhamim celebrated the intellect, and the suspension of common sense was not a prerequisite to the study of Talmud. In their eyes, Midrash and Aggadah are rabbinic rhetoric that consist of idiomatic metaphors, riddles, parables, and folklore.[14] Derashot (rhetorical and hermeneutic tools of exegesis) and gematria (numerology) were not the source of laws, but rather a rabbinic art and creative language used, symbolically, to express connections, lessons, and moral instruction derived through human logic and received tradition.

A traditional Sephardic approach to education places far more emphasis on Mikra (Scripture), precise Hebrew grammar, familiarity with Mishnah, and halakhah le-ma’aseh (practical application of Jewish law), rather than on commentaries, Talmud study for its own sake, and pilpul (hair-splitting textual analysis).[15] The notion of kollel for the masses was unheard of because, in the Sephardic world, only the most advanced students would proceed to Gemara, attend yeshiva, and eventually, in many cases, enroll in rabbinic academies where they would be trained to become community rabbis.

Finally, but crucially, Sephardic Jews may be very diverse, but they shy away from sectarianism. There has always been a wide spectrum of observance and opinions, but that did not lead to denominational splits or new factional movements. As a result, congregational rabbis were forced to deal with a whole range of societal issues and less-than-ideal situations far more frequently than their Ashkenazic counterparts in the shtetl and in their segregated Orthodox communities. As a result, less-observant Sephardic Jews continued to see themselves as part of the community, and the general tolerance shown towards those less committed meant that the door was open to a much wider circle of Jews.

Having broadly surveyed the history and conceptual underpinnings of the classical Sephardic approach, I return to the issue of its declining popularity. What happened to the classical Sephardic tradition?

The Decline of the Classical Sephardic Tradition

While the classical Sephardic approach has been overshadowed by other competing attitudes and ideologies, its fire has never been completely extinguished, and it remains a living tradition. Granted, it manifested and evolved differently in Amsterdam, Livorno, Philadelphia, Constantinople, or Salonica as it did in Meknes, Alexandria, Sana’a, Baghdad, or Damascus. Nonetheless, the tradition which championed Torat Sefarad and many of its original core principles has survived the test of time.

The classical intellectual tradition, though, has suffered, and there are several possible reasons for its near demise and why it has been largely marginalized within, or perhaps by, mainstream Orthodoxy. Firstly, the general Sephardic-Ashkenazic population divide has enormously shifted. While Sephardic Jewry comprised over 90 percent of world Jewry in the year 1170, five hundred years later it was about fifty-fifty. By 1900, 90 percent of Jews were Ashkenazic.[16] This dramatic demographic swing combined with the socio-economic conditions (that partly caused this reversal), as well as all of the consequences of a minority becoming subsumed within an overwhelming majority, provides some important historical context that can help us understand how and why the Sephardic tradition has waned.

Furthermore, there are several significant historical factors that account for the decline of the classical Sephardic tradition, such as the Maimonidean controversies of the Middle Ages. The fiery clashes and polemics that began to surface among proponents and opponents of philosophy and Maimonides during the last years of his life, and then again, repeatedly, in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, majorly impacted the course of Sephardic history. The bans and threats drew many away from the predominance of philosophical speculation and caused many to turn to Kabbalah. The spread of the Zohar, and then later Lurianic Kabbalah in the 16th century, undermined the classical Sephardic tradition by providing a cohesive framework independent from science and non-Jewish wisdom, thus negating the utility of external studies and the rationalist thinking that typified the Andalusian philosophical approach. Since then, the further popularization of the Zohar and mainstreaming of kabbalistic teachings continued to displace and eclipse many of the ideas and ideals of the classical Sephardic approach.[17]

The decay of the classical Sephardic tradition can also be attributed to external circumstances. During the Islamic Golden Age of Spain, the Jews lived in relative peace and harmony with their Muslim overlords and Christian neighbours, and they were part of a highly advanced and sophisticated culture.[18] This engendered a pluralistic environment which was conducive to the pursuit of knowledge and intellectual accomplishments. As less tolerant Islamic sects took control of Arab lands and following the devastating pogroms of 1391 throughout Castille and Aragon, the conditions were no longer as favorable to the classical Sephardic approach as they had been in earlier times.

With the rise of religious persecution, there was a shift away from abstract philosophical and scientific thought towards Kabbalah. It is understandable why, in times of suffering and hardship, the corpus of eschatological literature proliferated and many Jews found intellectual refuge in the enchanted, mysterious, and hopeful world of Kabbalah in which each action, no matter how insignificant, is endowed with cosmic significance. As a result of these circumstances and influences from surrounding magic-oriented cultures, a popular religion that is into segulot (charms) and superstition has prevailed among large swathes of the Sephardic populace. Many of these practices and beliefs stand in contrast with the ideals of the classical Sephardic tradition.[19]

Conclusion

Today, we live in an enlightened age of information and science. We have technology at our fingertips that can grant us access to all branches of knowledge. We live in an era where access to higher education is unparalleled and going to university is the norm. We live in a time when Jews have more freedom to practice their faith than at any other time in history. In this climate, the classical Sephardic tradition that once blossomed can again be fruitful and thrive.

We need to promote a Judaism that can comfortably synthesize its universalist ideas with its particularist narrative. A Judaism that shapes and informs the world but is also shaped and informed by the world. A Judaism whose body might temporarily be in the West but whose heart is constantly in the East. A Judaism that will elevate Israel and enable it to fulfill its providential duty to be a light unto the nations.

It is, therefore, incumbent on Sephardic Jews to reclaim their past and set it as a model on how to live a traditional life in the modern world, actively engaged in both God’s Word and World. Let us heed the call of Rev. Dr. Henry Pereira Mendes urging for “a revival of Sephardic activity, a renewal of Sephardic energy, an earnest demonstration of fidelity to God and Torah, [and] a continued proof by our own lives that culture and fidelity can go hand in hand.”[20]

It remains our duty to reinvigorate this ancient and beautiful tradition, amplify its distinct voice, and le-hahzir atarah le-yoshnah, to return the crown to its former glory.

[1] For more on the “Ashkenazification” of Sephardim, see Daniel J. Elazar, The Other Jews: The Sephardim Today (New York: Basic Books, 1989), xii, 203.

[2] As the historian Yom Tov Assis writes, “Sefarad is cultural and religious more than geographical and political.” See “Sefarad: A Definition in the Context of a Cultural Encounter,” in Encuentros and Desencuentros: Spanish Jewish Cultural Interaction throughout History, ed. A. Doron (Tel Aviv, 2000), 35.

[3] See, e.g., Yehudah Ha-Levi’s “My Heart is in the East,” and Abraham Ibn Ezra’s “The Lament for Andalusian Jewry,” in Peter Cole’s The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492 (Princeton University Press, 2009), 164, 181.

[4] See a variant in the foreword to The Eight Chapters of Maimonides on Ethics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1912), 35-36.

[5] See Shu”t Hatam Sofer OC 1:28. This phrase originates in Mishnah Orlah 3:9. R. Schreiber’s reactionary response should be understood in the context of the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement. See Jacob Katz, “Outline of a Biography of Hatam Sofer” (1968), republished in Katz, Halakha ve-Kabbalah (Jerusalem, 1984), 353–386.

[6] Rabbi Hayyim Yosef David Azulai (Hida) attributed the traits of hesed and gevurah to the respective approaches towards halakhah. See Rabbi Binyamin Lau, Ha-Hakhamim, vol. 1 (Beit Morasha, Jerusalem, 2007), 196.

[7] Rabbi Hayyim David HaLevi, Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv (1924-1998), writes about how halakhic innovation is testament of the Torah’s eternity. See Micah Goodman, The Wondering Jew: Israel and the Search for Jewish Identity (Yale University Press, 2021), 170. For case studies on Sephardic halakhic creativity, see Zvi Zohar, Rabbinic Creativity in the Modern Middle East (A&C Black, 2013).

[8] See, e.g., Rev. Dr. Henry Pereira Mendes’ remarks in 1891, cited in Marc D. Angel, “Thoughts About Early American Jewry,” Tradition 16 (1976), 12.

[9] While this attitude and these methodological principles are of course not exclusively Sephardic, they represent the classical Sephardic halakhic norm and tendency. See Ariel Picard’s analysis of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef’s approach to halakhah in “Freedom, Liberty and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef,” Havruta Journal (Fall 2008).

[10] Maimonides, Hilkhot Sanhedrin 4:11. In 16th-century Safed, there was an attempt to renew semikhah and reinstitute a Sanhedrin by Rabbi Jacob Beirav and Rabbi Yosef Karo. See Mor Altshuler, “Rabbi Joseph Karo And Sixteenth-Century Messianic Maimonideanism,” in The Cultures of Maimonideanism: New Approaches to the History of Jewish Thought (Brill, 2009), 191-210.

[11] Yosef Messas, Collection of Responsa 1:161. See also Radbaz, Responsa, part 4, no. 1368.

[12] See Jose Faur’s introductory remarks in The Horizontal Society: Understanding the Covenant and Alphabetic Judaism, 2 vols. (Academic Studies Press, 2019), Section IV, 215 and Section II, appendix 6, 54.

[13] See, e.g., Sa’adia Gaon in Sefer Emunot ve-Dei’ot, Book VII; Maimonides, The Guide of the Perplexed, introduction or II:25; Yehudah Ha-Levi, Kuzari 1:67.

[14] Cf. Yitzhak Berdugo, Understanding Hazal (Da’at Press, 2022).

[15] In many places, the curriculum included secular studies and various languages that granted Sephardim access to different branches of wisdom. See Marc Angel, Voices in Exile: A Study in Sephardic Intellectual History (Ktav Publishing House, 1991), 180-188.

[16] Figures are taken from Arthur Ruppin, quoted in H.J. Zimmels, Ashkenazim and Sephardim (London, 1958), 97-98.

[17] See Yamin Levy, The Mysticism of Andalusia: Exploring HaRambam’s Mystical Tradition (MHC Press, 2023).

[18] For scholarly debates regarding the treatment of Jews and Christians under Islamic rule, compare María Rosa Menocal, The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain (Back Bay Books, 2002); Chris Lowney, A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain (Oxford University Press, 2006); Dario Fernandez-Morera, The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise: Muslims, Christians, and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain (ISI Books, 2016).

[19] Marc Angel, Voices in Exile, 16; see also José Faur, In the Shadow of History: Jews and Conversos at the Dawn of Modernity (SUNY Press, 1992).

[20] Rev. Dr. Pereira was Minister of Congregation Shearith Israel in New York, and delivered this sermon at Lauderdale Road Synagogue on July 27, 1901. See Eugene Markovitz, “Henry Pereira Mendes: Builder of Traditional Judaism in America” (PhD diss., Bernard Revel Graduate School of Yeshiva University, 1961), 250.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.