Seth Farber

In order to address fully the significance of the “newly” found article from the Boston Sunday Advertiser, one would have to understand the context in which it was written and the motivation of its author. As the article itself indicates, this record is some form of interview, “as told to Sybil Soroker.” She was a Zionist activist in Boston in the years following the war.

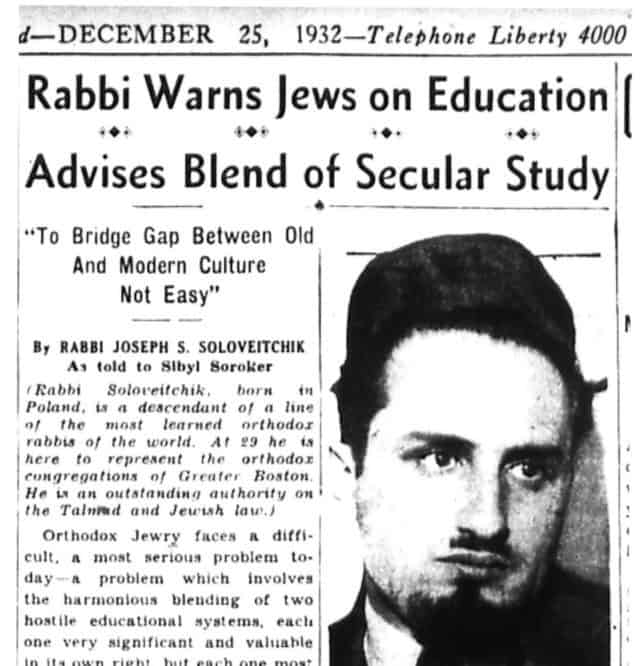

Why was the article published? Without trying to be anachronistic and assume that Rabbi Soloveitchik or his colleagues had engaged a public relations firm, I think it is safe to say that from the moment he exited in the train in the second week of December 1932, Rabbi Soloveitchik attracted significant public attention within Boston’s Jewish community. As I demonstrated in An American Orthodox Dreamer, Rabbi Soloveitchik’s arrival was “an event” in the Boston Jewish community and a number of articles were published in the Boston Jewish Advocate and Ha-Pardes relating to his first days in Boston.

From the very moment that he touched down in Boston, Rabbi Soloveitchik was driven to establish his unique Jewish educational agenda. Principally, I have argued, he accomplished this through his (and his wife’s) efforts at Maimonides School in Boston. It has always been my feeling that Rabbi Soloveitchik arrived in the United States, intent on making a significant contribution to American Jewish life.

Now, an article from the Boston Sunday Advertiser has come to light, which complements the arguments I made in my book: Rabbi Soloveitchik saw his role as revitalizing (or perhaps bringing to life) Jewish education in Boston. In order to catalyze the community, he utilized the press to “get his message out.”

It is within this context that the content of the “interview” should be understood. Rabbi Soloveitchik here was not—in my opinion—making a theoretical case for Torah u-Madda or the blend of Torah and secular studies. Rather, he was reaching out to a community that is overwhelmingly non-observant but committed to Orthodox Judaism in theory.

The “problem of Orthodox Jews” as the interviewer puts it, is to face the new modern realities; the need for secular education alongside religious education. The “historical” analysis provided in the first two sections of the interview is, in my opinion, an attempt to justify why the “melamdim,” the teachers, of 1930s Boston are not relevant to the average student. They came from a different era, and the needs of the youth are foreign to them. Rabbi Soloveitchik made a similar argument when he started the United Hebrew Schools a year later.

Thus, the main point of the interview comes when Rabbi Soloveitchik discusses the “boys and girls.” Rabbi Soloveitchik here identified his main audience: young children studying in Hebrew schools in Boston (and their parents). His main goal was to attract them to a more significant experience of study, an experience that he would attempt to create by leading a movement during his first years in Boston, first by trying to reform the Hebrew Schools and then by creating the Maimonides School. And, Rabbi Soloveitchik understood who he was competing against: The “Hebrew” culture which so dominated Boston’s Hebrew schools (as differentiated from heders) in the 1920s and 1930s.

Essentially, Rabbi Soloveitchik saw the Hebrew Schools as educational institutions which attempted to teach Judaism through the eyes of Bialik and through Hebrew culture, and the heders as anachronistic institutions that had no future. His call for the study of Talmud as essential to the Jewish experience was not meant to be understood as a plea to return to the yeshiva approach, but rather, to explain that Judaism has a future only if it is studied fully.

In this context, it is worth remembering the program that Rabbi Soloveitchik promoted, less than 11 months following the interview. The initiative, which was developed together with principals from the Bureau of Jewish Education schools, was published in the Jewish Advocate. In addition to fundamental knowledge of reading, writing, and spelling of Hebrew and familiarity with prayers, the new program emphasized the following cardinal points:

1. The Torah is to be studied in the original unabridged form, and to be interpreted in the spirit of the tradition and according to the commentary of Rashi.

2. The meaning of the prayers should be made clear and intelligible to the children.

3. Jewish history should be made familiar to the child in such a way that the great personalities of the past should captivate their affections.

4. Mishnah, Talmud, and ethics of the fathers should be made an integral part of the course of study. (Jewish Advocate, November 7, 1933)

In the end, this program was implemented in day schools throughout America (although in Maimonides School, the emphasis on prayers and their meaning took on greater significance). But at the time of this interview, the notion of a day school—or for that matter, any educational institution that could synthesize Judaism and secular studies—was not relevant. Instead, the interview as laid out in the newspaper, was an attempt, in broad strokes, of an educator to set out his educational vision, and begin a process of synthesizing traditional Jewish education with modern values and ideas.

During Rabbi Soloveitchik’s first years in Boston, all the Jewish students living in Mattapan, Roxbury, and Dorchester were studying in non-Jewish public or private schools. Thus, his focus was enhancing the Jewish after school programs. But he believed, from the outset, that a full Jewish and secular education was completely consistent with traditional Jewish values.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.