Zev Eleff

In October 2017, the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks told a large crowd at Yeshiva University that the “phrase ‘Modern Orthodoxy’ is overrated to the nth degree.” He reasoned that the Modern Orthodox were too tiny to stake it out on their own. Their disagreements with other Orthodox Jews were too “small” to require brand differentiation. “I urge you to find another label.”

Modern Orthodox Jews were the group that had emerged in the postwar period most committed to synergizing their commitment to middle-class America, Zionism, and observance of Jewish law. They were young and educated, and they had sought out a label that could provide a definition for their cause.

Rabbi Sacks had a point. Later that day, at a luncheon for the conference presenters—sans Rabbi Sacks—another panelist concurred with the former British Chief Rabbi’s sentiment, suggesting that there was no longer much separation between the Modern Orthodox and the so-called Yeshiva World on once pivotal issues such as college education and Zionism. He posited that the former was no longer so keen on liberal education. The latter, he alleged, no longer was so opposed to the State of Israel.

Pundits have also questioned whether Modern Orthodox politics vary from the Orthodox mainstream. I say mainstream because according to the Pew Research Center’s Portrait of Jewish Americans, those self-identifying as Modern Orthodox comprise just 30% of the American Orthodox community, totaling about 150,000 women and men. Several weeks before the presidential election, historian Joshua Shanes published an article full of trenchant observations on the right-wing political leanings of the Modern Orthodox, a trend that follows—but, he admitted, lags behind—the trajectory of the rest of Orthodox Jews in America.

However, I think the issue is more complex. The Modern Orthodox are a political unicorn. This group’s posturing resembles neither its Orthodox counterparts nor the larger American Jewish sphere. Politics might be one crucial reason why there is still a place for the Modern Orthodox Jew as a religious type, despite Rabbi Sacks’s judgment on the matter.

Orthodox Jews tend to vote Republican, at least when it comes to their preference for the occupant of the White House. The American Jewish Committee’s survey of Jewish voting behavior in the months leading up to the 2020 presidential election revealed that 74% of queried Orthodox Jews indicated their intentions to vote for President Donald Trump. The figure is staggering because it contrasts so vividly with the broader American Jewish landscape. The same survey reported that three-quarters of Jews in the United States had planned to vote for former Vice President Joe Biden. The number of those favoring Biden would have risen even higher were we to decouple the Orthodox quotient—about 10%—from the total Jewish population.

It was not always this way. Before the 1980s, Orthodox Jews voted in line with their American coreligionists. The reason for this is complex. The political scientist Kenneth Wald suggested that the Orthodox turn toward the GOP might have something to do with a shared interest in blurring Church-State doctrine, particularly in the case of government funding for public schools.

Recent observers side with Wald. Social scientists Ilana Horwitz and Laurence Kotler-Berkowitz found much of the same in their conversations with Orthodox Jews in Northeast Philadelphia. Many interviewees confided to Horwitz and Kotler-Berkowitz that they found Trump an “abomination.” However, the vast majority also said that they intended to vote for Trump anyway since they found his policies much more in line with conservative religious points of view. Orthodox Jews also overcame their feelings about Trump’s personal character to vote for him because of what interviewees described as Trump’s very solid support for the State of Israel. The historian David Myers agreed, placing the Orthodox vote into historical context and in coordination with right-wing Christian groups.

Yet, other data indicates that the Modern Orthodox’s voting behavior doesn’t necessarily match that of other Orthodox Jews. First, the northeast sector of Philadelphia is home to many more right-wing Yeshivish Jews than Modern Orthodox. Second, a dive into the Pew Research Center’s 2013 dataset—tabulated by Kotler-Berkowitz—shows that 77% of self-described Yeshivish Jews identify as or lean Republican. Just 22% of that population figures into the Democrat pool. The Modern Orthodox, even as the sample size is smaller than other groups, are split on party affiliation: 47% side with or lean Democrat and 46% gravitate toward Republican. The remainder claim a parve space as “independents.”

Pew also polled on political ideology, stripped of party affiliation. Among the Yeshivish group, 80% registered as politically conservative or very conservative. By comparison, only a third of the Modern Orthodox described themselves along the spectrum of political conservatism. A quarter of this group claimed space along the liberal flank of American politics. Most tellingly, 38% of the Modern Orthodox self-defined as moderates, a figure that significantly outpaced Yeshivish Jews.

All this implies that it is sensible to decouple the Modern Orthodox from the larger Yeshivish enclave. Some point out that religious elites across all Orthodox sectors have embraced Trump, including certain Modern Orthodox rabbinical organizations that have published praises of Trump’s policies. However, with the Modern Orthodox at least, the rabbinic position may not correlate with the much larger lay population. For example, earlier generations of Modern Orthodox Jews parted ways with their rabbis on hot-button issues such as the Vietnam War and access to contraception. The same is possible for the 2020 presidential election.

How did Modern Orthodox Jews vote in 2020? There are no exit polls dialing in on this small faith group. In 2017, I argued in a Lehrhaus article that day school mock presidential elections are a useful resource to obtain a better handle on this. I figured that student voting trends can approximate the voting behavior of their parents. Four years ago, tabulations submitted by 60 day schools indicated that Trump had garnered a majority of the Modern Orthodox vote.

I repeated the experiment in 2020. This time, I queried 80 Modern Orthodox day schools. I generated this fuller list from a census of Jewish elementary and high schools furnished by the late Marvin Schick and the Avi Chai Foundation. Half decided against holding mock elections, a much higher percentage than in 2016. These schools worried that polling would generate too much commotion. They found other ways to educate. For example, YULA Girls High School in Los Angeles did not host a mock election for similar reasons that the school decided against it in 2016. Political discussions are just too heated.

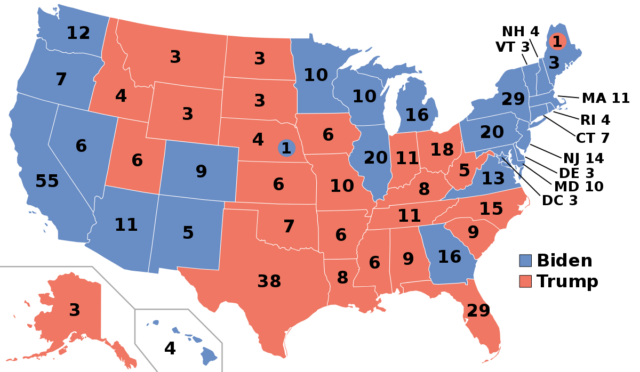

Instead, explained Social Studies Chair, Brian Simon, YULA students focused on civics education. “Our history classes all carefully taught the inner workings of the electoral college. Our students now understand the role of the popular vote and how it impacts the electoral process,” said Simon. “We also analyzed the political significance of swing states.” YULA’s boys and girls’ divisions also joined a student-driven debate that focused on political issues rather than candidates.

The results of the 40 schools that conducted mock elections prove just how unpredictable the Modern Orthodox vote can be. Four years ago, Trump dominated. In November 2020, Biden won most of the mock elections—34 to 16—within the day school circuit, but not by a wide margin. There were a few cases of total landslides; Biden and Trump collected an equal share: four apiece.

Why did Trump lose more Modern Orthodox mock elections this time? I asked day school administrators, especially those who work in schools that flipped to Biden in 2020. Some suggested that the impact of COVID-19 on day schools since last March likely figured into students’ decisions. “Many of our students implicate the government’s handling of the pandemic for the decision to close schools last spring and the strict precautions needed to resume school this year,” said one principal.

Other school leaders told me that young people are very informed on the issues. Like many Americans, they assessed the candidates’ positions and records on the economy, healthcare, and immigration to cast their mock vote. “Israel and the perception of who is better for it was not the only determining issue this time around,” explained a social studies chair who handles her school’s mock election program.

Several cases in particular were revealing. One school in the Tri-state area polled students and staff on a variety of issues. This school community voted on solidly liberal lines on climate change, abortion, and whether to abolish the electoral college. On Biden versus Trump, however, the Democratic nominee barely edged out the incumbent, 49-45%.

Another school took a similar approach. This one surveyed students: first on Middle East politics and then on Church-State policies. In this instance, the majority of Modern Orthodox girls and boys took the conservative stance on the Middle East and Israel but voted like moderate liberals on religion in the public square. On the presidential race, the students sided with Joe Biden, but barely.

The students voted in line with our knowledge drawn from survey data. According to the Pew data, the Modern Orthodox are moderates and liberal-leaners when it comes to most political issues. But, they flip on Israel. That coheres with Brandeis University’s 2015 community study of Boston Jews, one of the few such surveys that asked participants to measure their politics against lobbying groups. A crosstab of religious affiliation with the bipartisan and pro-Israel AIPAC is informative. Among those familiar with this lobbyist group, about three-quarters of Orthodox respondents (in Boston, particularly, most of these are likely self-identifying Modern Orthodox Jews) indicated that AIPAC either somewhat or very much matched their Israel politics. That figure was higher than Conservative (67%), Reform (44%), and Reconstructionist (19%) Jews.

That many perceived Trump better aligned with AIPAC’s mission complicated voting decisions for Orthodox Jews who hold this issue as very important, above—but not overriding—other significant political variables. Biden, of course, has also spoken at AIPAC conferences and received applause from attendees. Still, the messaging from pundits and politicians outside of AIPAC, in the newspapers and on social media, is confusing. It is a challenge for voters to make sense of this, and then to weigh these values against other deeply held beliefs. The parents, then, face the same predicaments as their school-age children.

The Modern Orthodox’s political arithmetic does not fit so neatly as it might for other Jewish groups. Positioned closer to the middle of the religious spectrum, their social networks reach liberal and conservative sections of American Jewry, a versatility that further complicates the Modern Orthodox’s voting behavior.

What, then, of the Modern Orthodox vote? They are the unpredictable swing state among America’s Jews.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.