Wendy Zierler

I am a professor of Hebrew literature and a rabbi. And as much as I can, I strive to bring these two parts of my life—the modern literary and the devotional aspects—in conversation with one another.

One way I do this is by giving a mini-class, every Tuesday after our local 6:45 a.m. daily minyan, in which I choose and translate a modern Hebrew poem and offer commentary on it in relation to the prayers, the weekly portion, or other matters of the day. I call the class “Shir Hadash shel Yom” (New Poem of the Day, a play on the traditional liturgical daily psalm), and I teach it out of a conviction that poetry is intimately connected to prayer, and that modern Jewish (and more specifically, modern Hebrew) literature can serve as a potent, relevant, contemporary form of commentary on our traditional sources.

Not just that: I believe that modern Hebrew literature provides a model for how that which came before us—the whole corpus of classical Jewish legal and literary sources—can be enlivened and revivified by what is happening now. The Hebrew poetry of Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000), for example, with its many references to prior liturgical and theological texts, combined with colloquial contemporary Hebrew, both extends and complexifies our understanding of classical sources, bringing all this prior meaning into conversation with current reality.

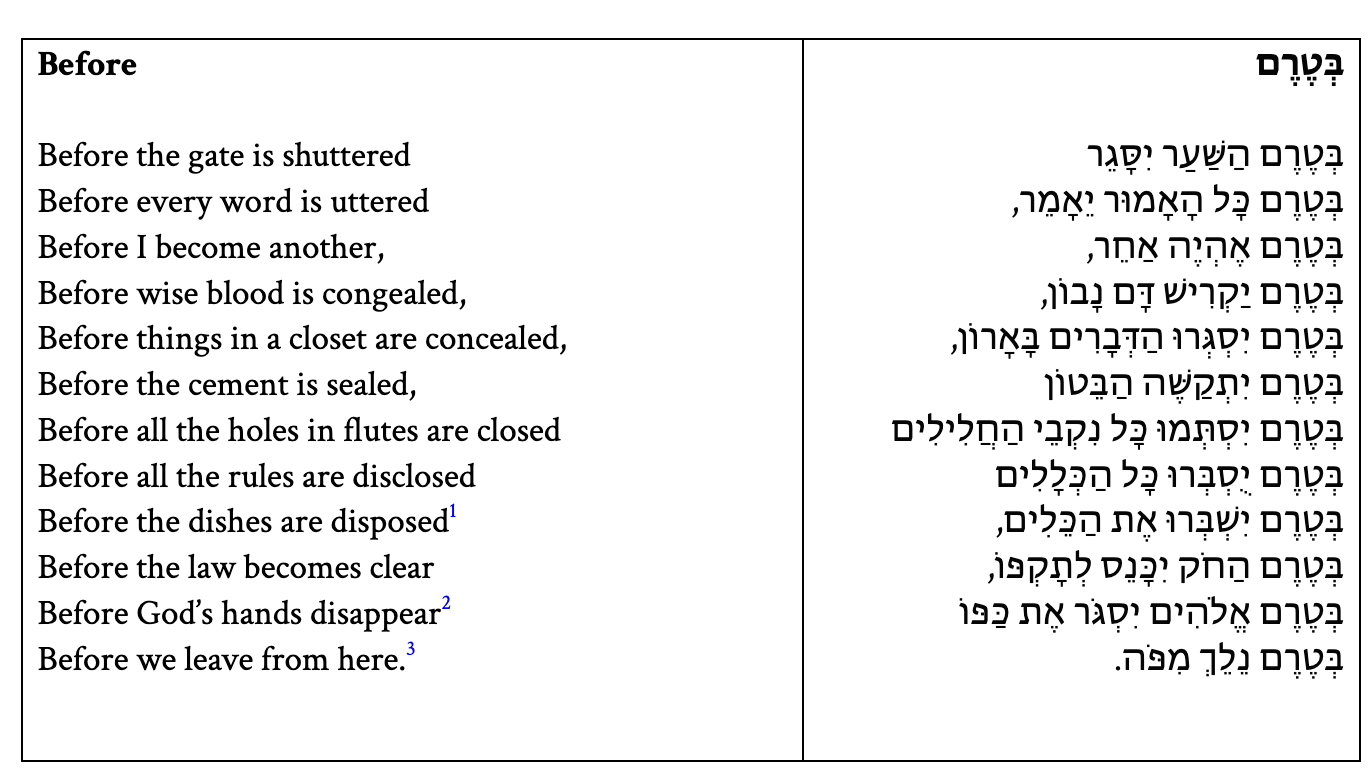

Perhaps the best example of this is Amichai’s poem “Beterem” (Before), which highlights the theme of “beforeness,” even as it intimates the crucial importance of the here and now:

Yehuda Amichai, “Beterem,” in Shirim 1948-1962 (Jerusalem: Schocken, 1963), 201.

“Beterem” is a poem that enchants the reader by way of its combination of accessibility and riddling complexity. In twelve short lines, Amichai offers a list of adverbial clauses, all pertaining to time: twelve tribes’ worth of transitional moments, before something important happens. The effect of linking these disparate moments into successive trios of rhyming lines is a combination of order and urgency, even anxiety. What will happen before each of these transitions? How can we make sense of these concatenations, and by extension, how do we make sense of our seemingly unrelated, consecutive life experiences?

Before I dive into interpreting the imagery chosen for these transitional moments, I would like to provide a few words on the various biblical Hebrew words for the English preposition before, all of which continue to be used in modern Hebrew, rather interchangeably.

There is lifnei, which literally means “to the face of”—beforeness construed here as standing or occurring in relation to a face. And there is kodem, which refers to east (kedem), and which most likely derives its meaning from the sun rising in the east before it sets in the west. Lifnei and kodem both combine spatial and temporal meanings.

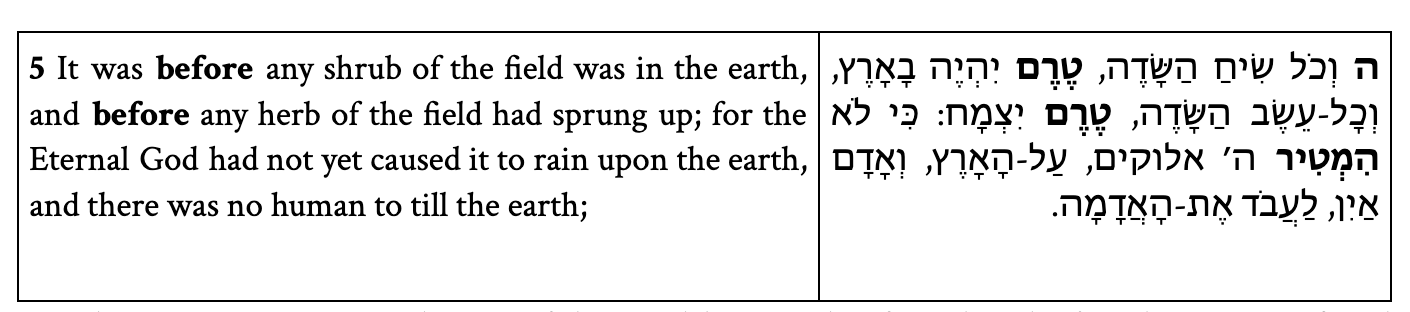

The one Hebrew word for before, which is exclusively temporal in meaning is “terem” or “beterem.” In fact, this is the first Hebrew version of the word before to appear in the Bible: in a description in Genesis 2:5 of an early stage in the creation of the world, before the creation of rain or plants or trees or human beings:

It is this primary or primeval usage of the word beterem that furnishes the first description of God in the famous piyyut “Adon Olam”—אֲדוֹן עוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר מָלַךְ בְּטֶרֶם כָּל־יְצִיר נִבְרָא—the Master of the universe who ruled before any other creature was created.

It is this primary or primeval usage of the word beterem that furnishes the first description of God in the famous piyyut “Adon Olam”—אֲדוֹן עוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר מָלַךְ בְּטֶרֶם כָּל־יְצִיר נִבְרָא—the Master of the universe who ruled before any other creature was created.

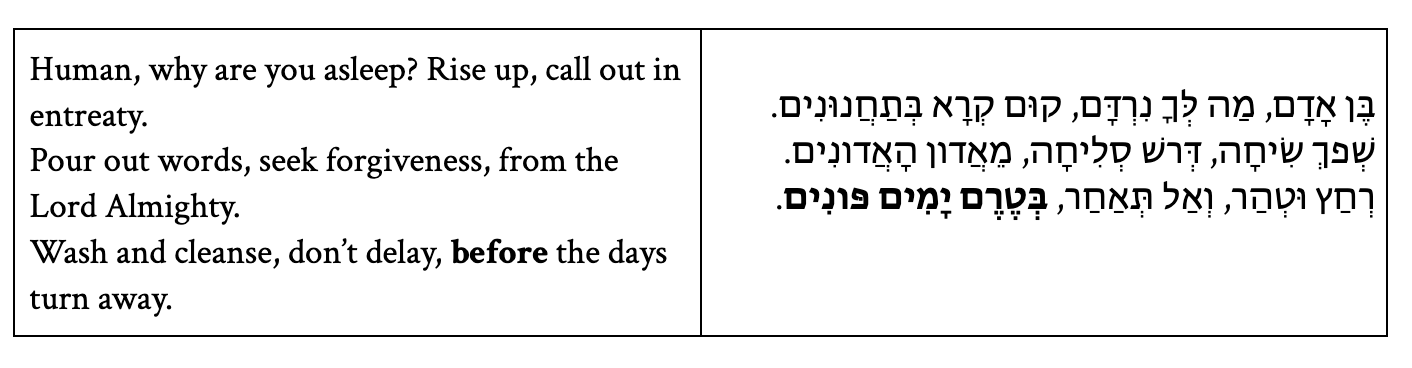

The word beterem thus takes on a kind of temporal priority, a status of liturgical “beforeness,” reflected in that fact that it appears in the first stanza of “Ben Adam mah lekha nirdam,” the first piyyut in the Edot ha-Mizrah nushah of Selihot, the last stanza of which reads:

In his book on Yehuda Amichai’s poetry, Israeli scholar Boaz Arpaly analyzes Amichai’s “Beterem” as a catalog poem—that is, a list of time descriptions and subordinate clauses without the accompanying independent clauses. It thus falls to the reader to be an interpretative detective and discern the common principle that connects the items in the catalog.

In his book on Yehuda Amichai’s poetry, Israeli scholar Boaz Arpaly analyzes Amichai’s “Beterem” as a catalog poem—that is, a list of time descriptions and subordinate clauses without the accompanying independent clauses. It thus falls to the reader to be an interpretative detective and discern the common principle that connects the items in the catalog.

What is meant to happen “before the gate is shuttered” or “the cement hardens”? What “wise” natural process has to occur before blood can “congeal,” allowing a scab to form over a wound and thus, for healing to take place? It’s up to the reader to fill in the blanks and to unite the various processes into an interpretive whole.

Arpaly sees the “befores” listed in Amicha’s poem catalog as both an optimistic call to do what you can before the rules are established, and as a pessimistic declaration about the inevitability of the after, which is mortality.[4]

Even though the idea of death is never directly stated in the poem, Arpaly is correct in seeing in the poem the specter of mortality. Those who are familiar with the varied usage of the preposition “beterem” in the Bible will note that this word features prominently in two before-death stories, first in Genesis 27:4, when Jacob summons his eldest son Esau to prepare him his favorite food and to bring it to him—בַּעֲבוּר תְּבָרֶכְךָ נַפְשִׁי, בְּטֶרֶם אָמוּת—“so that I can bless you before I die.” The same construct appears much later in Genesis in chapter 45:28, where Jacob, hearing that Joseph is actually alive not dead, declares: אֵלְכָה וְאֶרְאֶנּוּ, בְּטֶרֶם אָמוּת—“let me go down to Egypt to see him before I die.”

If the word beterem denotes the earliest or foremost before—beterem kol yetzir nivra, before existence of anything other than God—then the other end of the spectrum, the ultimate after, is death.

What Arpaly’s reading of the poem misses, however, with its binary focus either on the moment before one acts or the ultimate after of death, is in the in-between of the present moment, which Amichai’s contemporary colloquial style and incomplete sentences, evocative of actions-in-progress, so aptly capture.

Between beterem—that foremost before—and mavet (death)—that ultimate after—is the present-tense “during” of our lives, which like the reader of Amichai’s poem, we are tasked to endow with meaningful content. It is during that present tense that we endeavor to change and make a difference.

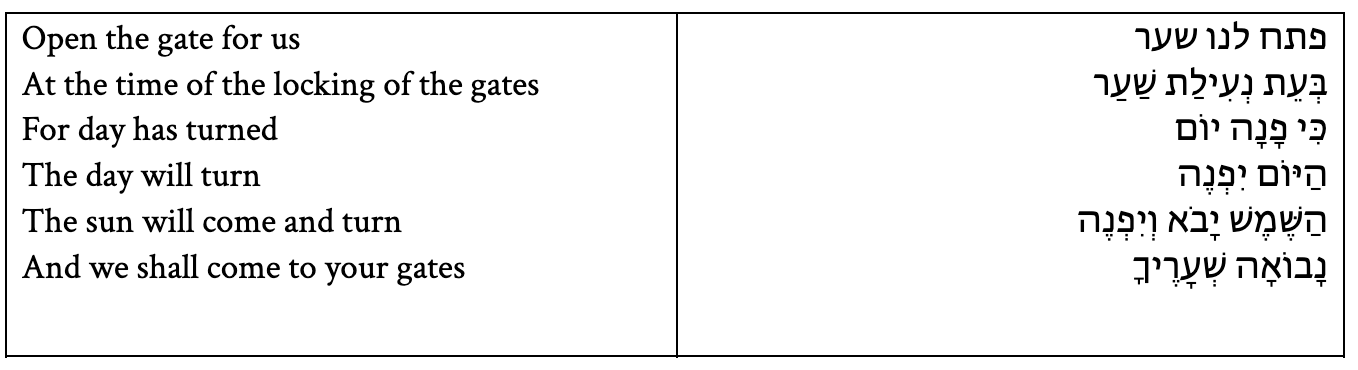

Amichai’s poem opens with a reference to a famous Neʿilah piyyut, which marks the end of the delimited period of repentance during the Hebrew months of Elul and Tishrei that constitute a concentrated form of “during.” The Neʿilah piyyut reads:

By opening with the words בְּטֶרֶם הַשַּׁעַר יִסָּגֵר—before the gates are closed—Amichai conveys the sense of urgency that attends the experience of Neʿilah, as emblematic of the existential time pressures and importance of the human present, not just on Yom Kippur, but throughout the normal “during” of our lives.

By opening with the words בְּטֶרֶם הַשַּׁעַר יִסָּגֵר—before the gates are closed—Amichai conveys the sense of urgency that attends the experience of Neʿilah, as emblematic of the existential time pressures and importance of the human present, not just on Yom Kippur, but throughout the normal “during” of our lives.

The High Holy Days begin with Rosh Hashanah and end with Yom Kippur, two days that embody beginnings and ends. The theme of the birth of the world, which is attached to Rosh Hashanah, reminds us of the beginning point of time—the foremost Before, or Beterem. On the other end of the spectrum is Yom Kippur with intimations of death. As Rabbi Irving Greenberg explains in his book The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays, “On Yom Kippur, Jews enact death by denying themselves the normal human pleasures… On this day, traditional Jews [wear white or] put on a kittel, a white robe similar to the shroud worn when one is buried.”[5]

These rituals attached to Yom Kippur remind us of the inevitable after–that is Death, and our duty to make the most of our lives before that time comes.

Filling the present-tense during of our lives with meaningful, impactful content is our seasonal as well as our lifetime challenge. The array of metaphors that stack up in Amichai’s poem remind us of life’s many possibilities and forms, expressed in the things we say, do, make, break, store, play, touch, and leave.

The elements in Amichai’s catalog are as different from one another as they are the same, embodying the concrete, literal, and secular, on the one hand, and the abstract, metaphorical, and liturgical, on the other.

There is the reference in line 2 to things being said, a description both mundane and holy, resonant of everyday conversation, of God’s speaking the world into existence in Genesis 1, as well as to the recitation of prayers.

A similar mix of mundane and holy appears in line 3 in the expression ehyeh aher, which can be translated simply as “I’ll become different”—as in the process of teshuvah, when one strives to become a better person, cleaving more closely to God’s commandments—or I’ll become an Aher, an Other or apostate, like the heretic Elisha ben Abuyah, and abandon the Torah entirely.[6]

The reference in line 5 to things being closed up in an aron is another such example, given that aron can connote either a closet, a bookcase, a synagogue ark, or a coffin. The various connotations of this word combine the semantic fields of the religious and the secular, as well as the various “durational” options of one’s lifetimes. One’s possibilities or identity can remain hidden in a closet, can be opened and explored like the books on a bookcase or the Torah in an ark, or can be forever sealed away with death, as if in a coffin.

Likewise, the reference in line 7 to the stopped-up openings of flutes (nikvei ha-halilim): one can play a flute only if one sufficiently covers its holes. At the same time, “nikvei ha-halilim” also reminds us of the asher yatzar blessing, which praises God for fashioning our bodies with wisdom and creating nekavim, nekavim, halulum, halulim (many openings and cavities), that if stopped off, result in death. The proximity of the word halilim (flutes) to halalim (battle victims) also adds another, especially somber intimation of mortality, that is, of lives cut tragically short by war.

And then there is the reference in line 9 to shevirat ha-kelim, a breaking of the vessels, which denotes wanton destruction but also evokes the Lurianic account of Divine Creation of the cosmos. According to this kabbalistic account, a cosmic breaking of the vessels occurred as part of Creation, scattering a mixture of shards and sparks throughout the world. From this account of the breaking of the vessels comes the call during the “during” of our lives to gather the sparks, perform mitzvot, and engage in the ongoing pursuit of tikkun ha-olam, of repairing the broken world.

Amichai’s poem is a call to action out in the world, but it also is a call to meditation and deeper consciousness of the value of every second in our lives.

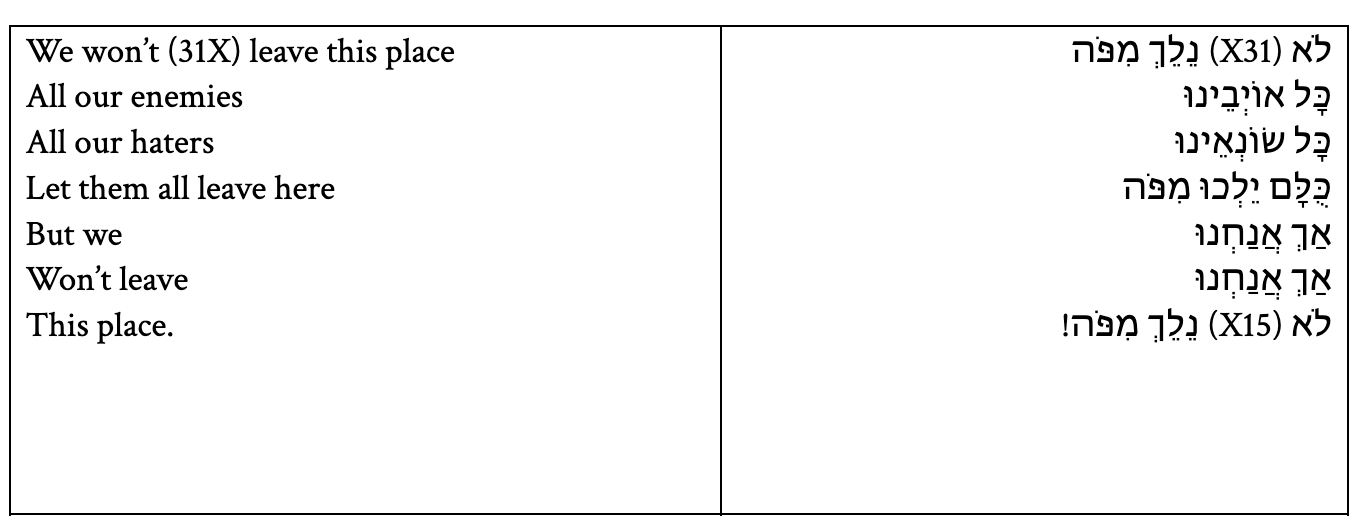

The final line of the poem, “Beterem nelekh mi-poh”—before we all get up and leave from here—drives all of this home. Set in a Zionist context, this line is a direct response to a classic Zionist poem/song by poet Avigdor Hame’iri (1890-1970), entitled “Lo nelekh mi–poh”:

Hame’iri’s poem/song, which includes more than thirty repetitions in each go-around of the word “lo” offers a stubborn statement of determination to stay put in the land. What Amichai’s poem acknowledges, and what we acknowledge every year at this time of year, is that even if we don’t want to, eventually, nelekh mi-poh—we shall indeed leave this place. No matter how determined we are to stay where we are, life eventually pushes us to that elsewhere and afterward of death.

Hame’iri’s poem/song, which includes more than thirty repetitions in each go-around of the word “lo” offers a stubborn statement of determination to stay put in the land. What Amichai’s poem acknowledges, and what we acknowledge every year at this time of year, is that even if we don’t want to, eventually, nelekh mi-poh—we shall indeed leave this place. No matter how determined we are to stay where we are, life eventually pushes us to that elsewhere and afterward of death.

Considered in the context of synagogue prayer, beterem nelekh mi-poh prods us to make something meaningful of that time, while we are still sitting in the pews, before we get up and go home, and/or before we leave this world.

Often we speak of redemption and change as taking some time in some far-off future, as in the Aleinu prayer, when we imagine a future, perfected messianic time when “God’s name” will finally “be One.” Or we seek out redemption nostalgically in the past, חַדֵּשׁ יָמֵינוּ כְּקֶדֶם, in the kodem/before times of our deceased ancestors.

What Amichai’s “Beterem” teaches, however, is that while we are enjoined to remember our past, and while we are charged to imagine a better, future day—the real work of repentance and redemption occur not in the past or the future, but in the durational present of our lives.

[1] Lit., before they break all the vessels.

[2] Lit., before God’s palm is closed.

[3] Lit., before we leave from here.

[4] Boaz Arpaly, Ha-perahim ve-ha’agartal: Shirat Amichai: mivnah, mashama‘ut, poetikah (Tel Aviv: Ha-kibbutz ha-meuchad, 1986), 105-106.

[5] Rabbi Irving Greenberg, The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 186-187.

[6] See for example, Hagigah 15b.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.