Moshe Simon-Shoshan

Over the course of his lifetime, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, known to his followers simply as the Rav, wrote a vast number of essays, articles and books, and he gave thousands of classes and lectures. The Rav’s oeuvre includes some of the greatest pieces of Talmudic analysis and Jewish philosophy ever composed. Yet in recent years, a relatively brief speech, popularly known as the “Mesorah Speech,” has attracted an extraordinary amount of attention in some circles.[1]

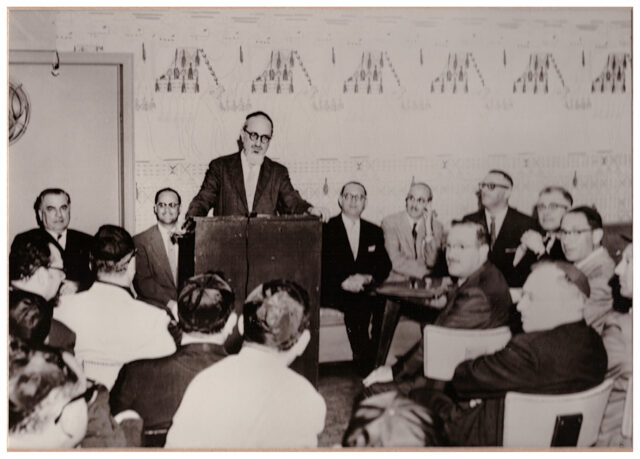

It is certainly understandable that some attribute great importance to the Mesorah speech. Early on in the talk, delivered at a meeting of Yeshiva University rabbinic alumni in June of 1975, the Rav declares, “What I am going to say… is my credo about Torah and about the way Torah should be taught and Torah should be studied.”[2] He proceeds to present perhaps his most eloquent and impassioned soliloquy about the experience of Talmud Torah. But it is clear from the opening lines that the Mesorah speech was an impromptu talk. The Rav never prepared it for publication as he did with other speeches. The quality of the recording is quite poor, suggesting that it was not recorded with the Rav’s permission. The Rav put a vast amount of time and effort toward other discussions of Talmud Torah that he thought worthy of publication. Despite declaring this speech to be his “credo,” these published works deserve more attention from those who seek to understand the Rav.

In this essay, I seek to clarify two aspects of the Mesorah speech as they relate to the Rav’s overall worldview.[3] First, the Rav’s general approach toward ideas he rejected and the individuals who held them: The Rav avoided attacking individuals for their ideas and positions and was loath to declare anyone a heretic or as standing outside the bounds of Orthodoxy. He did so in the Mesorah speech only reluctantly because he thought it critical to do so at that juncture. Second, I focus on the Rav’s approach to the academic study of Halakhah. In this speech, the Rav appears to staunchly oppose such methodologies. However, it is difficult to accept that the Rav held such an extreme position. In light of recently published evidence, the Rav’s position on academic methodologies was more nuanced than a simple reading of the Mesorah speech would suggest.

The Rav’s Non-Authoritarian Approach to Dissent

At the outset of his speech, the Rav emphasizes that the tone and content of his remarks are quite uncharacteristic of him:

You know me; I have never criticized anybody, never attacked anybody, and I have never set myself up as judge and arbiter, to approve or disapprove of statements made by others. However, today I feel it is my duty to make the following statement, and I am very sad that I have to do it.

Later in the talk, the Rav prefaces his use of the word “heretic” by stating, “I don’t like to use the word.” The Rav made an exception for the case at hand. He was responding to a halakhic proposal regarding the laws of divorce put forward by Rabbi Emmanuel Rackman. The Rav had a long and contentious relationship with Rabbi Rackman, a prominent talmid hakham, intellectual, and communal leader. Not long after this speech, the Rav vigorously opposed Rabbi Rackman’s candidacy for the presidency of Yeshiva University. The Rav felt that Rabbi Rackman’s proposal presented a unique threat to Orthodoxy, which required him to make use of rhetoric that he almost always avoided.[4]

The Rav’s disinclination to engage in ideological policing is further illustrated by a letter he sent to Rabbi Yitz Greenberg in September of 1965.[5] The Rav wrote this letter several months before Rabbi Greenberg became a lightning rod for controversy on the YU campus, following his interview in the Yeshiva College student newspaper and the heated exchange between himself and Rav Aharon Lichtenstein that appeared in subsequent issues of the paper. It was many years before Rabbi Greenberg began to publish his radical theological positions that generated much opprobrium in the Modern Orthodox world. At the time, he was a popular and influential faculty member at YU identified with the liberal end of the YU world.[6]

The Rav addresses the letter to “Rabbi Greenberg” and opens and closes with warm greetings to Rabbi Greenberg and his family on the new year. He continues:

There is absolutely no need of [sic] apologies or explanations. You are certainly entitled to your opinion as much as I am to mine. I have never demanded conformity or compliance even from my children. I believe in freedom of opinion and freedom of action (emphasis added)…all I said… was in the form of a hesitant (?) advice… [was] if I were invited, I would not accept. I did not instruct, nor did I try to convince you. Since you have made up your mind in accordance with your own view, all I can say to you is עלה והצלח, Go and may God be with you!

The Rav unequivocally states that he has never sought to impose his opinion on others. Rather, he believed that individuals have the right and obligation to come to their own conclusions and choose their own course of action.

In his dissertation on Rabbi Greenberg, Joshua Feigelson states that while “we do not know precisely what ‘participation’ [the Rav] referred to… given the circumstantial evidence, it is logical to conclude that the conversation was about Greenberg’s participation in the Jewish-Christian dialogue movement.” Feigelson goes on to note that Rabbi Greenberg himself tentatively confirmed this conclusion in a private communication.[7] This contextualization fits both the Rav’s and Rabbi Greenberg’s activities in the period leading up to writing of this letter. A year prior to writing this letter the Rav had published his now classic Tradition article “Confrontation” (1964), in which he laid out parameters for appropriate interfaith dialogue. The Rav strongly opposed any dialogue of a theological nature. That year, the RCA adopted this position as official policy.[8] During this same period, Rabbi Greenberg enthusiastically participated in theological interfaith dialogue.[9]

Accordingly, the letter illustrates how even regarding a passionately held theological stance, related to high-priority issues on the communal agenda, the Rav made no effort to impose his views on others. He extended this tolerance even to those of lesser stature, encouraging them to follow their own hearts and minds. Regardless of the letter’s original context, the Rav’s intellectual humility and pluralistic approach shine through.

Given his extreme hesitancy to attack others, I do not think that the Rav’s attacks on Rabbi Rackman in the Mesorah speech should serve as a precedent for harsh criticism of those whom we may see as following in Rabbi Rackman’s path, especially since no communal rabbi on the contemporary scene can match Rabbi Rackman’s power, influence and respect within the Modern Orthodox community at the time. Further, the Rav only publicly attacked Rabbi Rackman in response to a specific proposal that he saw as a particularly dangerous application of Rabbi Rackman’s overall approach. Applying the Rav’s polemics in this speech to positions, individuals, and situations other than those that drove the Rav to his extreme words requires great caution. Even if a particular contemporary position or policy clearly contradicts the Rav’s teachings, publicly attacking individuals who hold such positions is not necessarily in line with the Rav’s worldview.

The Rav and Academic Jewish Studies

The Rav rarely addressed the appropriateness of academic approaches to traditional Jewish texts. As such, the Mesorah speech is an important source for understanding the Rav’s thoughts on this matter. Nevertheless, due to their highly polemical context, the Rav’s strong stance against academic methods in this speech cannot provide a complete picture. Despite the simple meaning of his words, the Rav did not reject all academic study of Halakhah as illegitimate and heretical.

In the Mesorah speech, the Rav indeed took a very strong stand against academic methods. He declares that in the study of Torah,

It is ridiculous to say … I have discovered an approach to the interpretation of Torah which is completely new.” One must join the ranks of the hakhmei ha-mesorah — Hazal, rishonim, gedolei aharonim — and must not try to rationalize from without the hukei ha-torah and must not judge the hukim u-mishpatim in terms of the secular system of things…

The Rav goes on to suggest that such approaches are both inherently heretical and intellectually illegitimate, declaring that

You cannot psychologize Halakhah, historicize Halakhah, or rationalize Halakhah, because this is something foreign, something extraneous. As a matter of fact, not only Halakhah — can you psychologize mathematics?… I cannot give many psychological reasons why Euclid said two parallels do not cross, or why the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. If I were a psychologist I could not interpret it in psychological terms. Would it change the postulate, the mathematical postulate?

These lines imply an almost fideistic approach that rejects the use of modern empirical tools in the study of Halakhah. The statement suggests that many academic scholars who are otherwise talmidei hakhamim and yir’ei shamayim, are heretics, or at the very least enemies of Orthodoxy.

This apparently complete rejection of critical historical study of Halakhah belies the Rav’s general and nuanced approach to Jewish thought. Deeply influenced by Rambam, he mastered an astonishing range of academic fields and generally held the accomplishments of modern scholarship in high regard. The Rav was an epistemological pluralist who accepted the validity of multiple, even conflicting approaches to knowledge. Why, then, would he categorically negate the validity of one well-established academic approach?

These statements also appear incongruous with the Rav’s personal life. In this very speech, the Rav mentions that “every Friday morning from half past eight, for three hours until half past eleven, I study with my son-in-law.” His son-in-law was Rabbi Dr. Isadore Twersky zt”l, a professor at Harvard University. Professor Twersky was a pioneer in the historical study of rabbinic texts and personalities who had a vast influence not only on the American academy but on Modern Orthodoxy. Many of the Rav’s leading students studied in Prof. Twersky’s doctoral program and became prominent Orthodox rabbis, educators, and scholars. Rabbi Twersky succeeded his father-in-law as spiritual leader and posek of the Maimonides school in Boston. Similarly, the Rav’s only son is Rabbi Dr. Haym Soloveitchik, perhaps the greatest living scholar of the history of Halakhah. In addition to training generations of students at YU in the history of Halakhah, he also sometimes filled in for his father teaching Talmud to rabbinical students and at various points also offered his own Talmud shiur at YU’s Rabbinical School as well.

Did the Rav believe that his own son and son-in-law were heretics who threatened to destroy Orthodoxy? To be sure, despite the vast differences between their methodologies, Professors Soloveitchik and Twersky both advocated a conservative approach to the historical study of Halakhah, emphasizing the centrality of the internal logic of the Halakhah to its development. Nevertheless, according to the simple meaning of the Rav’s categorical attack on the historical study of Halakhah in any form, the answer to this would appear to be “yes.” But this conclusion is exceedingly difficult to accept. I am aware of no evidence that he held such opinions about two of his closest relatives and students.

Further, there is a certain inconsistency in the Rav’s own presentation of the halakhic methodology that he advocates in this speech. He states that these methods were revealed to Moshe on Mt. Sinai and are not in any way subject to change. Further, he asserts that there is no possibility of innovation or the discovery of new ideas in Halakhah that were not known to the great scholars of earlier generations. Yet, he also states,

the tools, the logical tools, the epistemological instruments which we employ in order to analyze a sugya in shabbos or bava kama are the most modern — they are very impressive, the creations of my grandfather. Anyway, we avail ourselves of the most modern methods of understanding, of constructing, of inferring, of classifying, of defining, and so forth and so on. (emphasis added)

This comment suggests that there are changes and innovations in rabbinic methods of Torah study. The Brisker method of the Rav can be considered modern, like the tools of contemporary scientists. As such, they differ from those used by earlier sages, producing new, unprecedented results.

How, then, are we to understand the Rav’s words and his position on academic Jewish studies? First, as Rabbi Herschel Schachter frequently notes, great rabbis sometimes talk be-leshon guzma, in an exaggerated, polemical style that cannot be taken literally. The wise student must know when a sage is using this rhetoric and interpret their words accordingly.[10] This fact might explain the intensity of the Rav’s polemic against Rabbi Rackman. Perhaps the Rav felt it necessary to adopt an uncharacteristically extreme tone in this speech that we should not take literally. Furthermore, the Rav reserved his ire not for academic scholars of Jewish history (Rabbi Rackman’s degrees were in law and political science) but for communal rabbis who, in the Rav’s his eyes, sought to pervert the halakhic process itself through the use of non-traditional methods.

Nevertheless, until recently, the Mesorah speech represented the Rav’s clearest available statement on the question of academic Jewish studies. Given that we can no longer ask the Rav to clarify his words there, suggestions that these statements cannot be taken at face value remained purely speculative.

Recently however, another speech of the Rav has become available to the public. This speech, delivered at the 1964 convention of the Rabbinical Council of America, is devoted to “The historical method applied to Halakhah” and deals with very similar issues to those treated in the Mesorah speech. In this earlier speech, the Rav appears to attack the approach to Halakhah advocated by the then-ascendant Conservative movement. At the time, the Conservative movement posed an external threat to Orthodoxy not unlike the internal threat the Rav contended with a decade later. In many ways, the two speeches are quite similar. As in the Mesorah speech, the Rav compares the work of the halakhist to that of the mathematician and the scientist. He argued that, just as the historical context of a scientific or mathematical truth bears no relevance to its veracity, so too the findings of historians and social scientists regarding the development of Halakhah cannot change Halakhah.

But this speech presents a far more moderate and consciously nuanced approach. The Rav opens with the following pronouncement:

The historical method, and you know what I am referring to, if not qualified and recklessly applied to the study of Torah she-baal peh, must lead to the denial of the principle of Torah min ha-shamayim, willy-nilly, and dispel the aura of kedusha which has surrounded the Torah she-baal peh throughout the ages. It will also, the historical method, if applied unreservedly and recklessly will also completely undermine the normative authority of Halakhah. Its imperatives, its mitvos will no longer be considered unconditionally binding. Men, selfish and pleasure seeking and petty, will invent many mitigating circumstances which will excuse him from strict compliance with the norm [?]. If Torah she-baal peh is placed exclusively in a historical perspective. (emphasis added).

In this formulation, the Rav clarifies that he does not delegitimize all historical consideration of Halakhah. He carefully emphasizes that his concern is not with the method itself, but with the potential for its abuse. As in the Mesorah speech, here too the Rav’s primary concern is with efforts to insert the methods of historians and social scientists into the halakhic decision-making process, not such scholarship in and of itself. Indeed, the Rav further qualifies his argument:

There is of course, there is certainly a history and a sociology of mathematics, certainly. Some social psychologists and sociologists may try to explain in their lingo why did…Euclid postulate his geometric system… Or someone may ask what psychological factors motivated Newton or Leibnitz to invent the calculus. As a matter of fact there is such a discipline under the name sociology of science…which is preoccupied with problems of this kind. However, this type of scientific investigation cannot be subsumed under mathematics. It has bearing only upon the psychological portrayal of the mathematician as an individual… It has however, no significance whatsoever as far as the study of space is concerned or the study of math is concerned… A sociologist or a psychologist interested in sciences as a social cultural phenomenon are not natural scientists or mathematicians, vice-versa the mathematician or physicist is not concerned with social cultural problems.

Just as the Rav recognizes that science has a history, so too he implies, does Halakhah. In keeping with his pluralistic approach to knowledge, the Rav simply seeks to keep these two disciplines separate. In this speech, the Rav clearly had no objection to academic scholars, including his son, son-in-law, and some of his other leading students, investigating the history of Halakhah, provided that they did not allow their conclusions to influence their halakhic decision-making process.

To be clear, as far as I know, the Rav did not have any deep interest in such endeavors, nor did he think that they were of great importance to Yiddishkeit. In this way, he differed from other gedolim, most notably, Rav David Zvi Hoffmann. A great posek, R. Hoffman was also a pioneer of the critical and historical study of Tannaitic literature. Similarly, the Rav’s good friend, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, the author of Seridei Esh, showed much more interest and openness to the use of academic methods than did the Rav.

Further, I suspect that the Rav’s concerns regarding the academic study of the sources of Torah she-baal peh went deeper than its potential influence on pesak. The Rav often emphasized, as he does at length in the Mesorah speech, that the study of Torah must be undertaken not only as an intellectual task but as a religious endeavor, engaged in a spirit of kedusha and yirat shamayim. Academic study does not require and even discourages such an approach. But the study of philosophy and natural sciences also have potential dangers. Indeed, one the central themes of The Lonely Man of Faith is the way the pursuits of “Adam I,” epitomized by the scientist, undermine the strivings of “Adam II,” the man of faith. Yet, the Rav put tremendous energy into mastering philosophy, mathematics, and the natural sciences, and he encouraged his students to follow similar paths. For the Rav, the potential spiritual dangers were not reason enough to prohibit an intellectual endeavor.

The Rav’s 1964 speech thus presents a much more moderate view of the historical study of Torah she-baal peh than does the Mesorah speech. I believe that the former speech is a more accurate representation of the Rav’s beliefs than the uncharacteristically absolutist rhetoric the Rav employed a decade later. In theory, it is also possible to explain the discrepancies between the two speeches by arguing that the Rav’s positions on these matters evolved over time. Those who embrace the Mesorah speech as their credo must recognize that at most, it represents the Rav’s thoughts at a particular moment in time and in response to a very specific set of circumstances. At other times, the Rav expressed different beliefs and positions.

More likely however, the Mesora speech is an important exception to the Rav’s general approach to ideas that he rejected and the people who held them. He was not in favor of extreme rhetoric, especially against individuals, and he did not write off any legitimate form of intellectual inquiry. However, he was willing at times to take strong stands when he felt core aspects of Orthodoxy were truly being threatened.

A few years after the Rav’s passing, Mori Ve-Rabi Harav Aharon Lichtenstein z”l urged us to “take Rav Soloveitchik at full depth,” declaring,

The shallowest cut of them all is the attempt to pigeonhole the Rav within the confines of a current narrow ‘camp’ … For decades… the Rav bestrode American Orthodoxy like a colossus, transcending many of its internal fissures. Let us not now inter him in a Procrustean sarcophagus.[11]

It has now been nearly thirty years since the Rav was buried in a humble coffin in the Beth El Cemetery in Boston. The better part of a century has passed since the Rav was at the height of his powers and influence. We live in a very different world, one that the Rav never saw nor could have envisioned. Rather than focusing on the details of the Rav’s halakhic, philosophical and public policy positions for his time, perhaps the most important way in which we can become students of the Rav is to learn his habits of mind and soul: total commitment to the study and practice of Torah, combined with an intense engagement with the intellectual, cultural and social currents of contemporary society; an approach to the world that emphasizes its complexity and nuance; a constant willingness to re-examine one’s own assumption and positions; and an aversion to extreme rhetoric and delegitimization of others, except when absolutely necessary.

[1] For an example, see Rabbi Steven Weil’s synopsis of this speech under the title “Mesorah: The Rav Speaks” in the Summer 2011 issue of Jewish Action.

[2] Citations from the transcript are posted here; the recording is available here.

[3] I will not address the Rav’s central concern there: the application of Halakhah to contemporary problems and issues. The philosophy of Halakhah lays at the heart of the Rav’s intellectual work. In order to avoid oversimplification, if not outright distortions of the Rav’s profound ideas about the nature and function of Halakhah, his comments on the nature of Halakhah in this speech need to be understood in the context of careful readings of his major works on the topic: Halakhic Man and The Halakhic Mind as well as critical passages in The Lonely Man of Faith, Mah Dodekh Mi-Dod, and other essays. Such an analysis is beyond the scope of this essay. I hope to address the Rav’s ideas about pesak Halakhah in a future piece.

[4] See Lawerence Kaplan, “From Cooperation to Conflict: Rabbi Professor Emanuel Rackman, Rav Joseph B. Soloveitchik, And The Evolution Of American Modern Orthodoxy,” Modern Judaism 30 (2010) 46-68, and the references cited there. For an evaluation of Rabbi Rackman’s persona and his contributions to American Orthodoxy, see Norman Lamm, “Rabbi Emanuel Rackman Z’l: A Critical Appreciation,” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 42, no. 1 (2009): 7-13.

[5] This letter, now deposited in the Greenberg archive at Harvard University, was transcribed and discussed by Joshua Feigelson in his doctoral dissertation, Joshua Feigelson, “Relationship, Power, and Holy Secularity: Rabbi Yitz Greenberg and American Jewish Life, 1966-1983” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 2015), 107-108. Dr. Feigelson has kindly supplied me with a facsimile of the original letter.

[6] For an account of Greenberg’s career at YU and his controversies with Rav Lichtenstein, see Feigelson.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Feigelson, 109.

[9] Ibid., 114.

[10] My own recollections of R. Schachter making such arguments were confirmed to me by his son, Rabbi Shai Schachter. Oral communication July 17, 2020. I thank Rabbi Dr. Zev Eleff for facilitating this communication.

[11] Aharon Lichtenstein, “Take Rav Soloveitchik at Full Depth,” Forward March 22, 1999, p. 6.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.