Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein

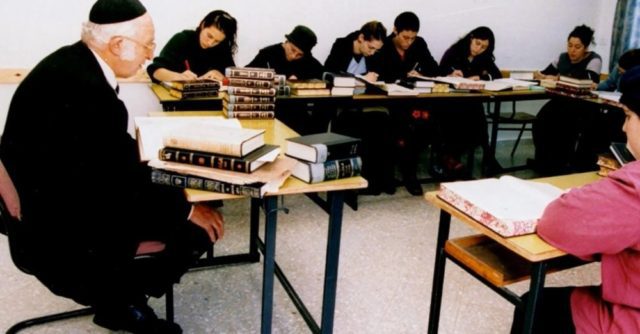

Editor’s Note: This document records remarks given by Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein, ztz”l, Rosh Yeshiva at Yeshivat Har Etzion, at the opening dedication, of Ma’ayanot Yeshiva High School for Girls of Bergen County, in Teaneck on November 24, 1996. Ma’ayanot, under the founding leadership of Rebbetzin Esther Krauss, saw (and sees) Talmud study as a cornerstone of its Judaic Studies curriculum, and Rabbi Lichtenstein was asked to provide remarks on women’s Talmud study in general. This text was transcribed by Terry Novetsky and edited by Rabbi Nati Helfgot, retaining the talk’s oral style. It has been previously disseminated by Ma’ayanot, but has never been published for general consumption. In light of recent articles on women’s Talmud study, The Lehrhaus sees fit to publish these remarks at this time.

Kevod Harabanim, Kevod Rebbetzin Krauss, staff, supporters, ladies and gentlemen:

In case you are wondering what I am doing here this morning, I suppose that I can simply respond that personal friendship with the Krauss family in general and Rebbetzin Krauss particularly would in and of itself warrant my presence.

Secondly, the fact that a number of our former talmidim of the Yeshiva, Yeshivat Har Etzion, were among the initial movers in establishing the school would also be sufficient reason.

Thirdly, the long-standing involvement, both ideologically and professionally, of my own family in the field of women’s education brings me here today to join in the dedication of the school. My mother, aleha ha-shalom, was actively involved in serious women’s education back in Lithuania in the 1920s. My father, alav ha-shalom, taught for close to a quarter century at Central High School in Brooklyn. The Rav, zikhrono le-verakha, of course, was a leader in stressing, in championing, the importance of intensive women’s education in all areas of Torah.

I myself spent, not in Torah specifically, six years formally teaching English Literature at Stern College, as well as being marbitz Torah informally. Above all, I am here not only because of any of these factors concerning the past. I am here because of a concern for the present and hope for the future.

My concern is with Torah and yirat Shamayim and harbatzat Torah and yirat Shamayim, with inculcating, promoting, and disseminating Torah. My concern is both for the study as well as the practice of Torah, lilmod ve-la’asot, in that whole area generally, and with profound appreciation of the importance, both at that level of study and implementation of this area, with regard to women specifically, regarded both as individuals and as a vital, dynamic force within the general community.

It is out of that concern, and out of appreciation of the wonderful experiment (and ultimately, of course, it will be much more than an experiment), that I am glad to be here this morning. It is in that context that I find myself presenting something of an ani ma’amim. A credo which, broadly speaking, perhaps relates to my own educational thought and practice, but which needs to be honed and sharpened and applied specifically with regard to the field of women’s education particularly.

What is the cardinal principle that lies at the heart, on the one hand, of Yeshiva education and, on the other hand, is the lynchpin of liberal education. It is, first and foremost, the notion that one is concerned with molding the person and only secondarily with preparing or training for the fulfillment of a certain role. John Cardinal Newman’s statement, that “we are men by nature, geometrists only by chance,” epitomizes this approach and it is one with respect to which, I have indicated, the Yeshiva world and the world of liberal education at its best coincide.

Of course, that is not to suggest that preparing for a role, be it a domestic role, a professional role, or a communal role, is not important. It is important, but secondary. The first principle, I think, with regard to education generally, and which needs to be particularly emphasized in the field of women’s education, is that first and foremost one needs to mold the person as an individual in all respects, with regard to character, personality, intellectual ability, and above all, of course, in religious terms, as an oved Hashem.

If we ask ourselves, what substantively does that molding entail? In answer, from a religious standpoint, it entails a dual focus. In part it is a development of powers, of ability, of capacity, which from a certain point of view is a kind of self-contained procedure, the Greek ideal, as it were, of paideia, bringing out of the person the potential that was inherent within him or her.

But from a Jewish standpoint, of course, the definition of “self” is itself not self-contained. Its primary focus is relational and the relation, of course, is to the Ribbono Shel Olam and to meeting His demands, aspiring to connect up with Him. And what those demands are, and therefore what our primary goal is, encapsulated in two celebrated pesukim in Parashat Ekev (Deuteronomy 10:12-13):

ועתה ישראל מה יקוק אלקיך שאל מעמך כי אם ליראה את יקוק אלקיך ללכת בכל דרכיו ולאהבה אתו ולעבד את יקוק אלקיך בכל לבבך ובכל נפשך לשמר את מצות יקוק ואת חקתיו אשר אנכי מצוך היום לטוב לך

And now Israel, what does the Ribbono Shel Olam demand of you, but to fear [if you will, to revere] the Ribbono Shel Olam, to follow in all His paths, to love him, and to serve the Ribbono Shel Olam with all your heart and with all your soul. To observe His commandments, His ordinances, which I commanded this day to your good.

In a nutshell, these verses ultimately encompass the whole of our entire existence. As you may note, these pesukim contain a dual type of demand. First, the Torah speaks as it were in generalities: to love, to fear, to serve, to imitate, to emulate. Then it goes on to speak of the nitty-gritty: לשמר את מצות יקוק ואת חקתיו, to observe His commandments, His ordinances. Of course, this lies at the heart of Halakhah generally, which on the one hand posits general goals and ultimate ideals, and on the other speaks of minutiae of se’ifim and se’ifim ketanim of Shulhan Arukh.

The world of the Halakhah is built on the condition that it is through the interaction of the broad and the minute that the totality of the human person, particularly of a Jewish person, is best built and the relation to the Ribbono Shel Olam is best maintained.

Now that this demand is one which is posited equally to men and to women—ועתה ישראל: The community as a whole, each and every individual, male or female, within that community. And this is the primary goal of education, certainly Torah education. But the pasuk presents this as if were a minimal kind of demand. “What does the Ribbono Shel Olamwant of you? Just this …” Hazal in the Gemara in Berakhot (33b), of course, raise this issue: “אטו יראשת שמים מלתא זוטרתא היא?”

Is fear of Heaven a small thing? Is it a kleinkeit? Only this? Hazal explain that this is formulated in relation to Moshe Rabbeinu, so for him it was somehow a minimal demand. For us, of course, it is not minimal at all; it is taxing, it is demanding, it is challenging, it is comprehensive. And, hence, its attainment requires the harnessing of energy, the channeling of effort, the imaginative intellectual pursuit which then translates itself into moral and religious categories in trying to build, first the individual, and through the individual interacting, as an interactive individual, the community as such.

If we ask ourselves: Here are the goals! “ליראה, לאהבה, לעבד, לשמר, לדבקה, ללכת בכל דרכיו,” to fear [God], to love [God], to serve [God], to cling [to Him] to go in all His ways.” What are the means? Traditionally, over the centuries, there has been a fairly sharp dichotomy precisely regarding this very issue, namely the means to be employed in relation to men versus women, even as the same goals of “ועתה ישראל” were known to be addressed to men and to women alike. Intensive study was central and crucial with respect to bahurim, with respect to men, while with regard to women, with regard to whom it was assumed, the emphases were to be different, perhaps the balance between Torah and hesed should be different, that aspect of intensive study was very often regarded to be different.

This is not the occasion to examine whether that was justified historically. What is clear, however, is that notwithstanding how one judges the past retrospectively, in our present historical and social setting we need to view the teaching and the learning of girls and women as both a major challenge, as well as a primary need.

Looking at the present particularly, in comparison to the past, two major differences could be noted. First, the need is greater; Second the opportunity is greater. As long as women led relatively sheltered lives, cloistered in their homes, married very early, imbibing observance, commitment, yirat Shamayim from their immediate environs, be it the home, be it the street, be it ambient culture, it was felt that as far as ensuring that a girl, a woman, would grow up suffused in yirah, in ahavah, le-dovkah bo be-khol derakhav, it was not terribly important to study Torah formally. And within a climate where general culture also tended to make parallel assumptions—as one English gentlemen in the seventeenth century stated, as far as he was concerned it was sufficient that his wife be able to tell the difference between his doublet and his hose—there was not pressure either. In addition, there was no keen danger that a girl who was not being taught Torah intensively was going to study something else intensively.

Today, of course, where there is so much exposure to cultures and countercultures, le-mineihem, when various ideological whims that are inimical to yirat Shamayim, yirah and ahavah, are the order of the day, then surely the need for study and intensive study is clearly there.

When the Bais Yaakov movement began, criticism was leveled against that project as well. Critics contended that it was not traditional; it was a departure from what was done previously; it involved too much study. The Hafetz Hayyim was then asked about it. His response was, and he was very supportive, that the Rambam (Issurei Bi’ah 14:2) says that when a person comes to be mitgayyer, to convert, apart from what the Gemara mentions in Yevamot (47b) that you teach the details of particular mitzvot, you also discuss certain theological principles, ikkarei ha-dat. Is it conceivable, then, asked the Hafetz Hayyim, that a girl who wants to be mitgayyer should be taught ikkarei ha-dat, and a girl who is born to a Jewish home should not?

Leaving aside for the moment the question of some kind of inherent hiyyuv with regard to talmud Torah, with regard to which clearly there are differences between men and women, with regard to scope and with regard to the character of that study, at the very least, that which Rishonim mention that women too say birkat ha-mazon, (though the text speaks of receiving the mitzvot of berit milah and Torah, of which they are seemingly not included) because, with regards to those areas of Torah which impinge upon their practice and observance, they certainly need to learn, and are obligated to learn.

Taking that as a principle translated to our current reality, that means, of course, that there exists an obligation for a girl to study the halakhot of niddah and taharat ha-mishpahah, and also kashrut and Shabbat because these impinge on her daily life. What is intended is that we need to ensure, minimally, that the depth of intensity, knowledge, and sensitivity which are needed in order to assure commitment, even if we are not interested for the moment (if that be the case) in the knowledge per se, but instrumentally, as molding a woman in becoming an ovedet Hashem, a keli in serving the Ribbono Shel Olam, that certainly needs to be studied. And, of course, within the modern context, that applies to areas of Torah that are far, far remote from the level of practical implementation. It is entirely conceivable, that in order to assure that a girl should be genuinely a ma’amina and an ovedet Hashem and to be shomeret Shabbat, ke-dat ve-ka-din, you need to be able to address yourself to a question that she may have about the world of korbanot.

Moreover, today there is not only greater need, there is also greater opportunity. Greater readiness, communally speaking, to engage women seriously, intellectually in general terms and with regard to Torah particularly. We have been zokheh in this generation, in Eretz Yisrael and here as well, to see the spread of serious and intensive Torah study at levels which by and large were not prevalent only a generation or two ago. That is an opportunity which certainly we want our daughters to take seriously out of the conviction that, quite apart from assuring the fundamental shemirat ha-mitzvot and yirat Shamayim, even with that assured, out of the conviction that deepening their involvement in talmud Torah, that that is going to enrich and enhance them as religious personalities, as ovdei Hashem.

Even as there is, on the one hand, a greater need in order to assure the minimum, there is a greater opportunity in striving for the maximum. If I ask myself, essentially, what should the process of talmud Torah be all about for a girl particularly, but not only for a girl? I would focus on one term which has a very, if you will excuse the phrase, feminine meaning to it, which I think has a great deal to say with regard to the significance of talmud Torah, particularly with regard to women.

I spoke before of developing the self, on the one hand, and building and preparing for a role, on the other. If we ask ourselves, the level of the role, what specifically has the Torah designated as the women’s role? “היא היתה אם כל חי,” “she [the primordial woman] is mother of all living beings” (Genesis 3:20). The process of being a mother contains a dual aspect. At the heart of motherhood lies bonding, and bonding by definition is reciprocal. It is, on the one hand, giving, and, on the other, a possession, as it were, giving life and being able to connect up, to give love and to receive it.

Talmud Torah for women, particularly, although broadly speaking for men as well, is a process of bonding. Bonding with who and bonding with what? At one level, of course, with Torah. Developing not only the knowledge but an existential link not only in one’s head, but with every fiber of one’s being, to feel connected to Torah, to be sensitive, to be appreciative, to understand its worth and appreciate its centrality. That is something, which, again, perhaps at one time was attained by other means, but which today requires, to a great extent, direct confrontation, direct involvement with Torah proper.

There is, secondly, a bond, not only with Torah as a body of text, of halakhot, but with that which Torah demands of us, with shemirat ha-mitzvot, with observance. I recall many years ago in a conversation with mori ve-rabbi Rav Hutner, z”l, in which the Rosh Yeshiva discussed with me whether one should learn masekhtot which are practical or those that are remote from the world of practice.

He was in favor, inter alia, of including in the curriculum of Yeshivot Gevohot masekhtotwhich are of practical relevance, a component that had not been central to Lithuanian Yeshiva education. He said to me, you know, if a bahur would know that saying keriat shema after zeman keriat shema is like taking a lulav on Hanukkah, he would get up earlier. But it is not only the sense of how to stress basic practice, if you get up earlier or don’t get up earlier. Even if the boy gets up at the right time and he says keriat shema be-zemano, what is the nature of that keriat shema, what is the quality of that mitzvah?

One of the things in which we need to invest ourselves with regard to religious education generally is to move away from a purely quantitative focus—not only “How many things does a person observe?” but also “How does he or she observe?” The Ramban, in a celebrated passage in the Sefer ha-Mitzvot (Hasagah to Aseh 5), discusses the meaning of the mandate of “le’avdo be-khol levavkhem,” or avodah she-ba-lev. In contrast to the Rambam, who sees this passage as the source for the biblical obligation of tefillah, Ramban sees this verse as relating to the practice of the entire corpus of Torah.

The Torah demands of us observance that is infused with full kavvanah, with total commitment, with passion, with the engagement of the whole of one’s personality. We are bidden to take the lulav not only with the hand, but with the heart, with the mind. That requires an engagement, requires a meeting of the whole of one’s personality with the world of mitzvot. And in this sense, too, serious study is significant.

The pasuk, of course, speaks of le-dovkah bo, to cleave onto Him, to bond with the Ribbono Shel Olam through His Torah. The Sifri (piska 33) further addresses our issue in its comments to the pasuk of ve-ahavta et Hashem Elokekha. How, asks the Sifri, do you attain the love of the Ribbono Shel Olam? So, of course, there are various avenues, but one of them, the Sifri says, referring to the following pasuk in keriat shema, “ve-hayu ha-devarim ha-elleh asher anokhi mitzvekha ha-yom al levavekha”—“and these matters which I commanded to you this day shall be engraved upon your heart” (Deuteronomy 6:6): תן הדברים האלה על לבך שמתוך כך אתה מכיר את מי שאמר והיה העולם ומדבק בדרכיו, “Place these matters upon your heart, learning Torah. Through that you attain love for the Ribbono Shel Olam and you cleave unto His ways.”

If we speak, then, of the mitzvah of ahavat Hashem: was that given only to men? It is a universal mitzvah and a prime and cardinal mitzvah, likened to the heart, the very central organ of the human being upon which experience and Jewish experience particularly rests. If we appreciate that Torah is a prime vehicle for attaining ahavah (leaving aside for the moment the independent mitzvah of talmud Torah as a separate test), that the mitzvah of ahavat Hashem, one of the ultimate goals, is achieved through this prime vehicle. Should we let that rust and sit idle with respect to our daughters and employ it only with our sons?

What we need to bear in mind, practically speaking, is that this process of bonding, so critical, so crucial to the molding of our daughters as servants of the Ribbono Shel Olam, requires that their learning be not only comprehensive, but above all serious. Learning must be approached seriously. The halakhic basis for this seriousness is the pasuk in Va-Ethannan (Deuteronomy 4:9): רק השמר לך ושמר נפשך מאד פן תשכח את הדברים אשר ראו עיניך ופן יסורו מלבבך כל ימי חייך, “Take care, guard your soul very much, lest you forget anything of what your eyes have seen and lest these somehow escape from your heart.”

According to the Ramban, this is a mitzvat lo ta’aseh, a negative injunction counted as one of the 613 commandments in the Torah. As we well know, while women are exempt from certain, specific positive commandments, such as those that are time-bound, all negative injunctions are incumbent upon them, including the injunction never to forget, never to be oblivious to, what occurred at mattan Torah. This injunction includes not to be oblivious to the meaning of mattan Torah both as an occasion, an experiential high, as well as to the meaning and significance of the micro-substantive content of revelation. Here, too, it behooves us to remember the mishnah in Avot (3:8), which records that a person who forgets a single matter of what he has learned or forgets it willingly has transgressed this lav. It is, in a word, the message of commitment, intensity, and seriousness.

Approaching this issue seriously, we need to take a dual focus. First, out of respect for Torah, and, second, out of respect for women. Out of respect for Torah, we collectively are the custodians of Torah. To be shomer Torah is in one sense to observe in daily life its commandments. In another sense, it is to guard it, to see that it remains pure, that it not be adulterated by false ideologies or by deviant theories. And it means, among other things, to guard its integrity and to assure that its quality and essential character be sustained.

In the Rambam’s discussion of the study of Torah She-Be’al Peh for women, he addresses himself to the rationale behind some of the strictures that we find regarding this area. He writes (Hilkhot Talmud Torah 1:13) of a concern that: הן מוציאות דברי תורה לדברי הבאי לפי עניות דעתן, “out of a certain simplicity or a certain limited development, they might take divrei Torah and transform them into something that is vacuous and empty.”

If Torah is to be taught, it needs to be taught out of a concern for its integrity, not just taking divrei Torah and somehow trying to present it as something very superficial and limited, because one is “only” educating a girl. Such an approach is in a way debasing of Torah and opening up the possibility that divrei Torah and devarim shel kedusha, the treasures of the Ribbono Shel Olam, will somehow be transformed into דברי הבאי. If Torah is to be taught at all, and be taught it must, certainly in our contexts, then it needs to be taught seriously, to assure that indeed Torah is understood and absorbed with the seriousness and with the earnestness, with the exhilaration, with the excitement, the passion that is coming to it.

But secondly, not only respect for Torah requires this of us, but respect for women as well. Respect for their abilities, their commitment, for their potential which is inherent within them and if you want to mobilize this force for themselves and for the good of the community. What that means, of course, is maintaining standards that are demanding and challenging. In practice, of course, it means not simply teaching digests of digests, but a confrontation, at a basic level, with primary texts.

I had occasion some years ago to meet with the staff of a high school for girls, an established high school for girls in Yerushalayim. They asked me for my opinion regarding certain aspects of women’s Torah education. I said to them, “I have been around the world of Yeshivot for close to forty years, and I never heard that people are learning what your girls are learning.” My nieces, when they used to attend that institution, would tell me that they are learning “Toshbap.” At first I didn’t know what it was. Then I realized it was an acronym for Torah She-Be’al Peh. And I said to those teachers: “You know, when a boy goes to Yeshiva he learns Bava Kamma, he learns Bava Metzia. He learns the Rambam, he learns Shulhan Arukh. He learns the Ketzot, he learns Reb Hayyims. But this ‘Toshbap,’ this kind of undefined, amorphous reality, that is not meat, that is not serious.”

The mitzvah, then, mandates that there must be a confrontation with the primary texts in a primary way. A way which, on the one hand, will challenge the mind and, on the other hand, will commit the heart. We should inculcate, on the one hand, the need to understand, and the need that takes as its point of departure profound faith and yirat Shamayim and therefore enhances that yirat Shamayim. A desire lehavin u-lehaskil, which then issues into a desire lishmor ve-la’asot. We need to develop within that individual an infusion of knowledge, sensitivity, and, above all, that spirituality which links, which bonds to the world of spirit to the world of the Ribbono Shel Olom.

All of this is in order to meet the first goal, that of developing the person, developing the individual girl. But, ultimately of course, it is through developing the individual that we mold and build a community, not with the process being dichotomous or bifurcated, but interactive. In part interactive, of course, because part of building yirat Shamayim is training for hesed, and inculcating the value of hesed. And with that particular emphasis upon hesed which relates to the specific focus of women’s education. So the training for hesed is part of the building of the self, and the building of the self is that which directs into the community, into the giving. That giving, which goes with the bond that I mentioned before, is not simply an egocentric oriented goal.

The school here has chosen as its name, “Ma’ayanot.” In the world of Halakhah, the term ma’ayan is graced with special significance. There are two foci of obtaining purity, the more familiar mikveh and the ma’ayan. What defines a mikveh, and this is of course the etymology of the word, is a certain measure of stagnation. A mikveh that is not stagnant is pasul. The water that does not stay within the confines of the mikveh but flows in and out, comes under the rubric of the Halakhah of mayim zohalin. Such a mikveh is pasul, because, by definition, it is not a mikveh. A mikveh means water that is collected and stationary.

A ma’ayan, on the other hand, virtually by definition, is dynamic; there is movement, there is vitality, there is growth. With regard to Torah, what ones seeks is not simply Torah of mikveh, although that is in one sense a base, a fundamental acceptance and foundation, but a Torah of growth, of life of vitality. A ma’ayan that is mitgabber or nove’a, the fountain which overflows, which the mishnah at the end of Bava Batra (10:8) states is characteristic of nezikin particularly, but characteristic, of course, of the world of Torah generally.

It is my hope and prayer that, indeed, for the kind of learning, the kind of growth, the kind of education broadly considered in reference to Torah and yirat Shamayim, which in turn will be transmitted and developed, this institution will indeed reflect its name: vitality, growth, challenge, stimulus with regards to all aspects of the personality, anchored in yirat Shamayim and out of that anchor, moving, growing, living in various directions. You have been zokheh to much siyata de-shmaya until now, as has been mentioned previously. Yehi ratzon, that you shall be zokheh to a long, wonderful path in the future with much more siyata de-shmaya.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.