Jeremy Brown

As many synagogues are closed for Shabbat, and others limit the numbers who may attend, the time seems right to see what our rabbinic tradition has to say about a new phrase that has entered our lexicon: social distancing.

There is a long history of isolating those with disease, beginning with our own Bible:

As long as they have the disease they remain unclean. They must live alone; they must live outside the camp. (Lev. 13:46)

Command the people of Israel to remove from the camp anyone who has a skin disease or a discharge, or who has become ceremonially unclean by touching a dead person. (Num. 5:2)

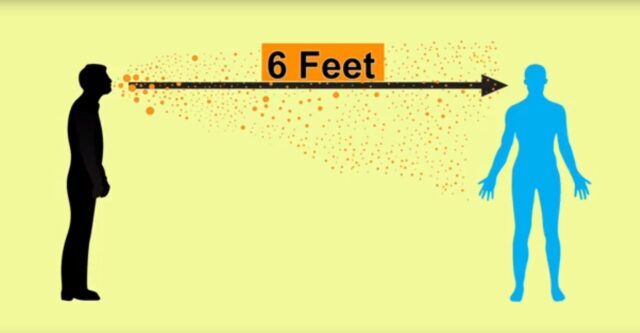

These are examples of social isolation, that is, individual and community measures that reduce the frequency of human contact during an epidemic. Here, for example, are some of the ways that social distancing was enforced during the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-1920, an outbreak that killed about 40 million people worldwide:

… isolation of the ill; quarantine of suspect cases and families of the ill; closing schools; protective sequestration measures; closing worship services; closing entertainment venues and other public areas; staggered work schedules; face-mask recommendations or laws; reducing or shutting down public transportation services; restrictions on funerals, parties, and weddings; restrictions on door-to-door sales; curfews and business closures; social-distancing strategies for those encountering others during the crisis; public-health education measures; and declarations of public health emergencies. The motive, of course, was to help mitigate community transmission of influenza.[1]

The Talmud emphasizes not the isolation or removal of those who are sick, but rather the reverse – the isolation of those who are well:

Our Rabbis taught: When there is an epidemic in the town keep your feet inside your house. (Bava Kama 60b)

Of course the effect is the same: there is no contact between those who are ill and those who are well, but since there are usually many more well than there are sick, the effort and social disruption of isolation of the healthy will be much greater.

It is not hard to see a relationship between expelling those who are ill and denying entry to those whose health is in doubt. In the 14th century, when Europe was ravaged by several waves of bubonic plague that killed one-third of the population, many towns enacted measures to control the disease. Around 1347 the Jewish physician Jacob of Padua advised the city to establish a treatment area outside of the city walls for those who were sick.[2] “The impetus for these recommendations,” wrote Paul Sehdev from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, “was an early contagion theory, which promoted separation of healthy persons from those who were sick. Unfortunately, these measures proved to be only modestly effective and prompted the Great Council of the City to pursue more radical steps to prevent spread of the epidemic.” And so the notion of quarantine was born. Here is Sehdev’s version of the story:

In 1377, the Great Council passed a law establishing a trentino, or thirty-day isolation period. The 4 tenets of this law were as follows: (1) that citizens or visitors from plague-endemic areas would not be admitted into Ragusa until they had first remained in isolation for 1 month; (2) that no person from Ragusa was permitted go to the isolation area, under penalty of remaining there for 30 days; (3) that persons not assigned by the Great Council to care for those being quarantined were not permitted to bring food to isolated persons, under penalty of remaining with them for 1 month; and (4) that whoever did not observe these regulations would be fined and subjected to isolation for 1 month. During the next 80 years, similar laws were introduced in Marseilles, Venice, Pisa, and Genoa. Moreover, during this time the isolation period was extended from 30 days to 40 days, thus changing the name trentino to quarantino, a term derived from the Italian word quaranta, which means “forty.”

The precise rationale for changing the isolation period from 30 days to 40 days is not known. Some authors suggest that it was changed because the shorter period was insufficient to prevent disease spread. Others believe that the change was related to the Christian observance of Lent, a 40-day period of spiritual purification. Still others believe that the 40-day period was adopted to reflect the duration of other biblical events, such as the great flood, Moses’ stay on Mt. Sinai, or Jesus’ stay in the wilderness. Perhaps the imposition of 40 days of isolation was derived from the ancient Greek doctrine of “critical days,” which held that contagious disease will develop within 40 days after exposure. Although the underlying rationale for changing the duration of isolation may never be known, the fundamental concept embodied in the quarantino has survived and is the basis for the modern practice of quarantine.[3]

In addition to staying indoors, the Talmud recommends two other interventions during a plague:

Our Rabbis taught: When there is an epidemic in the town, a person should not walk in the middle of the road, for the Angel of Death walks in the middle of the road…

Our Rabbis taught: When there is an epidemic in the town, a person should not enter the synagogue alone, because the Angel of Death deposits his tools there… (Bava Kama, ibid.)

It probably won’t surprise you to learn that neither of these two measures is discussed in the medical literature, and in fact if there’s an epidemic in town, you probably shouldn’t go to shul at all. Jewish behavior during an epidemic is even regulated in the Shulhan Arukh (Yoreh De’ah 116:5):

In addition, it has been written that one should flee from a city in which there is an epidemic. You should leave the city as soon at the start of the outbreak, rather than at the end. All these issues are a matter of life and death. To save yourself you should stay far away. It is forbidden to rely on miraculous help or to endanger yourself…

The suggestion made by the rabbis – to isolate yourself from others during an epidemic – is a basic part of public infection control. We’d be wise to listen. And as we sit in relative isolation, perhaps now is the opportunity to recite this long-forgotten Talmudic prayer, originally composed by Yehudah bar Nahmani, the secretary of Reish Lakish:

Master of the worlds, redeem and save, deliver and help your nation Israel from pestilence, and from the sword, and from plundering, from the plagues of wind blast and mildew [that destroy the crops], and from all types of misfortunes that may break out and come into the world. Before we call, you answer. Blessed are You, who ends the plague. (Ketuvot 8b)

[1] Institute of Medicine (IOM), Ethical and Legal Considerations in Mitigating Pandemic Disease, Workshop Summary (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007).

[2] Susan Mosher Stuard, A State of Deference. Ragusa/Dubrovnik in the Medieval Centuries (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), 46.

[3] Paul Sehdev, “The Origin of Quarantine,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 35 (2002):1071–2.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.