Yoel Finkelman

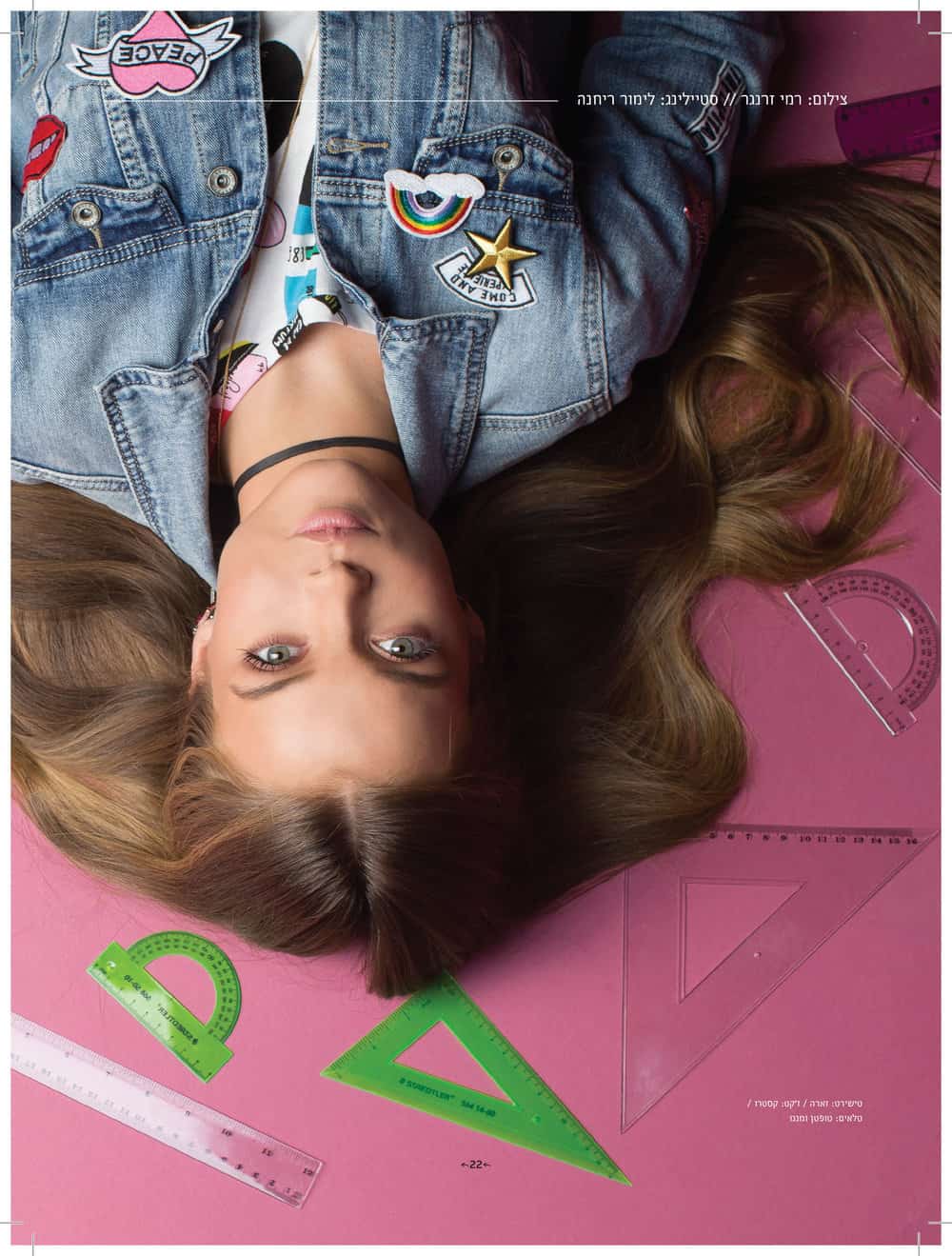

The girl’s face on the cover of the first issue of Nashim Teens, the new Hebrew magazine for religious-Zionist girls, exhibits no discernable human emotion, but it remains familiar nonetheless. Her expression says loud and clear, “I am a very attractive model, and I’m posing for the cover of a fashion magazine.” This expression, imitated in countless selfies, has never been seen among humans in their natural habitat, but in captivity on your local newsstand, it is quite common. Her t-shirt commands in big black letters: “Be You”—a nice sentiment, even if it is not immediately obvious what the alternative might be.

Orthodox Jews are used to following commands from on high, and they generally expect the nuances of the commandments to be spelled out in great detail. Nashim Teens, the first issue of which appeared last week, does not disappoint. By following the magazine’s instructions, you can be yourself—that is, you can be thin, be attractive, try to be famous, and most importantly buy the clothing, makeup, and accessories which appear in the advertisements or sponsored content on virtually every page of the new publication. The irony of achieving individuality through the purchase of mass-produced consumer goods is lost in the glare of the glossy photos.

And there are many, many glossy photos. Some photos of pretty models are expressly identified as advertisements—for Zip, Golbary, Fox, (major Israeli fashion brands) and a smaller boutique studio offering “modest dresses for girls and women.” Others are sponsored content, no doubt paid for directly by manufacturers: page after page of photos of winter clothing, makeup, and accessories, each identified by brand name and, of course, price. The titles leave no room for doubt: “Style Trends,” “Lipstick” (complete with photos of celebrities like Selena Gomez, Miley Cyrus, and Kendall Jenner—whose value as role models for modern Orthodox girls is questionable, to say the least), “The Wisdom of Clothing,” and “A Like for Nail Polish” (the Hebrew is alliterative: “Layk Le-laque”).

In between the fashion advertisements there are three actual articles—the kind with whole sentences and paragraphs that continue for more than one page. One is an interview with a non-religious Israeli actress. She is, of course, thin, beautiful, and very, very successful. Whatever message it is meant to contain is reinforced a few pages later, where a secular Israeli female model offers personal advice to readers in a short profile.

The second article is a feel-good piece about teen girls from around the world who have come on Aliya on their own, without parents and family. Good for them.

The third article is a four-page discussion of how frustrating it is when girls’ high schools enforce dress codes and obsess about skirt length. There is a lot to talk about here, and the issues really matter. The article speaks of the antagonism created by enforcing dress codes, the mixed feelings young women have about the matter, and the tension between conformity and individualism. It includes voices of students, teachers, and school administrators in conversation with one another.

The article itself is pretty good, and the issue is an important one, but it is telling that this article plays up tension between religious teens and their Torah education, especially when read in contrast to the non-religious actress, who speaks of how much she enjoys her secular high-school experience.

T-shirt by Zara, jacket by Castro, and so forth, with a block quote saying: “When they let me choose for myself, I am much more connected to my external presentation. It doesn’t come from a place of coercion, but from a place of connection to my deepest self.” Photos courtesy of Tekhelet Tikshoret.

T-shirt by Zara, jacket by Castro, and so forth, with a block quote saying: “When they let me choose for myself, I am much more connected to my external presentation. It doesn’t come from a place of coercion, but from a place of connection to my deepest self.” Photos courtesy of Tekhelet Tikshoret.

It is also worth noting that the most substantive article in the magazine is still about clothes, reinforcing the message that advertisers and fashion-magazine editors want readers to internalize: you are what you wear. To be something positive you must wear something positive. To wear something positive you must buy something positive—not what your principal tells you to buy, but what our magazine tells you to buy. An entire magazine dedicated to telling teenage girls how to dress features a lead article explaining how annoying it is when people tell teenage girls how to dress. There is no irony like utter lack of self-awareness.

Of course, there is a difference between religious authority figures who dictate how you must dress in order avoid punishment and please God, and fashionistas who dictate how you should dress in order to look great and please stockholders. But make no mistake. School dress codes and fashion magazines are in precisely the same business: policing female clothing, as part of a larger project of policing women’s bodies.

This magazine is not particularly “religious” in terms of content, but its target demographic is students in religious-Zionist girls’ high schools, especially from the Ashkenazi middle class with disposable income. It assumes that they attend schools that are not co-educational.

Two shorter pieces actually do say something about Torah, spirituality, and observance. The “La-neshamah” (“For the Soul”) column, written by a well-known female educator, speaks of the winter rains as a spiritual blessing. The short article is decorated by winter fashion choices. And the “Gibor Tarbut” (“Culture Hero”) column introduces a male celebrity singer, Yishai Revivo, who speaks glowingly about his time in yeshiva, his daily prayers, and the musical inspiration he gets from reading the Bible. That a man is the most overtly religious figure does not do much to foster the empowerment of religious women, but apparently exceptions can be made for celebrities.

The editors like playing with just a hint of transgression—the models wear tight jeans, even as they cover more skin here than in analogous secular magazines, presumably to avoid irritating religious customers. Photos of a girls’ basketball team wearing shorts is cropped so you will only notice if you look carefully. The minor transgressions are, of course, about clothing, because, well, that is what matters.

But despite this rather modest (no pun intended) willingness to push the envelope, one topic is verboten: romance and sexuality. There is none of the discussion of dating, attracting boys, and romance you would find in every secular teen fashion magazine—not because these things don’t exist; they certainly do. The target demographic is very different from the gender-separated Hardal world. They participate in co-educational youth groups, have male friends, boyfriends, and are in some cases sexually active. But the magazine doesn’t talk about that.

Actually, there is one sentence that addresses sexuality, easily missed as it is buried in a series of half sentences on a full two-page spread about the wonders of lipstick: “90% of women who wear lipstick say they do so in order to raise their self-confidence, and not in order to attract men.” There is certainly much truth to this, and there are many reasons why women or men might choose to invest time and money in dressing fashionably. But the absence of any discussion of male-female romance, certainly in the context of a teen fashion magazine, is surprising, to say the least. No other fashion magazine in the world thinks that women’s attractiveness can be entirely separated from sexuality. Even the religious educational system—hardly a model of a free and open exchange of ideas on these matters—understands that there is a connection between fashion, clothing, and sexuality, and that’s precisely why its educators are so uptight about clothes. One suspects that the editors had their tongues planted firmly in their cheeks as they wrote this sentence. They wink at sexuality by denying its role in their product. “Don’t worry,” they say, “there is no male gaze to be found on these pages.” Why the sudden puritanism in a magazine that is fooling nobody about co-ed relationships, in which relationships with boys and young romance is always hovering in the background? Why not ask what teens, educators, and parents think and feel about the phenomenon, or at least acknowledge the existence of the issues?

But the editors lack the guts—at least at this stage of the roll-out—to talk about it, and risk raising the ire of educators and parents who might prefer that religious teen romance be nipped in the bud. Thus, the one area where a magazine for religious-Zionist girls might actually be able to broach an important subject that the educational system fails to deal with adequately is the one area where this magazine adopts conventional Orthodox pieties, to a fault.

My complaints are not against the publishers, who are not obligated to produce a didactic or wholesome magazine. They are beholden only to their stockholders and to the bottom line. They will produce what customers will buy and what advertisers will pay for. My critique is addressed to the audience, who, if the editors’ market surveys are correct, see no incompatibility between religion, femininity, and unabashed consumerism.

Materialism, especially in its consumerist variety, is rarely the stated priority of citizens. Nobody makes an open ideological statement of commitment to accumulating stuff, in the way they might commit to the complete Land of Israel, states’ rights, limited monarchy, or the Meretz party. Rather, materialism wins when it becomes the unstated ground we walk on or air we breathe, when it becomes a harmless pastime, when we are not aware enough, or at all, of how marketers manipulate us into deeply desiring just that next object that we don’t yet have, and that until yesterday we didn’t even know existed.

With any luck, this magazine will fail, or at least be forced to modify its vision. With any luck, the consumers—young religious teenage girls and their parents—will teach the fashion industry a lesson. Is that too much to hope for from a religious-Zionist community in possession of such deep wellsprings of idealism and dedication? Can’t we aim just a little bit higher?

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.