Wendy Amsellem

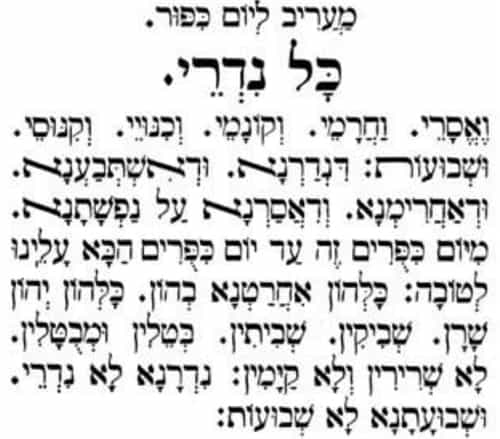

Vows and their undoing resound throughout the high holy days. Many individuals recite a formula annulling oaths and vows on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, and virtually all communities begin Yom Kippur with the Kol Nidrei prayer. Given that few of us can actually recount any vows or oaths that we have undertaken recently, why focus on this?

In both biblical and rabbinic literature, vows are a very serious matter. Numbers 30:3 cautions, “If a man vows a vow to God or swears an oath to forbid something to himself he shall not violate his words, all that he says, he must do.” The Bavli (Ketubot 72a) warns of the unbearable consequences of breaking a vow, “for the sin of [breaking] vows, children die.” Given the nature of what is at stake, we may want to undo any potential vows before we are judged, just to be safe.

Our focus on vows at this time of year, though, is about more than just precaution. Instead, taking vows and annulling them are a meditation on what it means to be human.

First, let’s explore why vows were so seductive. If a person took a vow, for example, to refrain from eating chocolate, the Torah commands her to keep her vow, and so the prohibition for her to eat chocolate would be on the level of a Torah violation. This is an extremely powerful use of language. Our words have the capacity to take on divine force, to really mean something. (This might explain why the Bible in Numbers 30:4-17 assumes that fathers and husbands would want to curb this power.) Even though the Mishnah in Nedarim 2:5 warns that only the wicked take vows, rabbinic literature is full of stories of rabbis and other highly reputable persons who engage in vow making.

We can understand the allure, the desire to speak significantly, to impose a steadfastness on our inherently mutable existence. We want to be more noble in our speech, more reliable in our actions. Yet the anecdotes about those who take vows always seem to end with a desire to get out of the vow. The nature of being human is to aspire to be God-like and then to fall short. We are unable to meet our commitments; we don’t want the same things tomorrow that we want today.

Bavli Nedarim 21b relates that a man came before Rav Huna with a vow to annul. Rav Huna asks him one question, לבך עלך, is your heart with you? Do you still want what you had wanted? When the man responds no, Rav Huna frees him from his vow.

The Bible never indicates that a person can be relieved of a vow. Indeed, the rabbis famously assert in Mishnah Hagigah 1:8 that “the annulling of vows floats in the air and has [no biblical basis] on which to rest,” yet there is almost always a way out of a vow. Generally the basis for annulment is חרטה, regret. The vow-takers adduce that there were circumstances beyond their cognizance at the time the vow was taken that now have led them to reconsider the vows. Or more simply, as in the above story about Rav Huna, the vow-takers do not want what they used to want. There is a debate (see Bavli Nedarim 77b) about whether others can help the vow taker articulate his or her regret or whether s/he must express the regret independently. Either way, it is the changeable nature of people that frees them from their divine ambitions.

Being extremely careful and cautious when taking a vow does not seem to help. Bavli Nedarim 22b tells of Rav Sehorah going before Rav Nahman to annul a vow:

Rav Nahman said, “Did you vow with the knowledge of this?” [Rav Sehorah] said, “Yes.” “With the knowledge of this?” [Rav Sehorah] said, “Yes.” This [exchange] was repeated several times. Rav Nahman became angry and said, “Go to your place!” Rav Sehorah left and found an opening for himself . . . “I did not vow with the knowledge that Rav Nahman would get angry at me.” [In this way] he freed himself from the vow.

The story underscores that the annulling of vows involves a legal charade. Rav Nahman is angered because Rav Sehorah is not playing along appropriately. Yet, the story also contends that even those who think long and hard before vowing eventually want to be free of their vows and need to rely on ingenuity to annul them.

Although Rav Sehorah frees himself from a vow, Shmuel teaches (Bavli Hagigah 10a) that it is preferable to have others annul one’s vows. Numbers 30:3 enjoins that one should not violate one’s own vow and oath, but Shmuel argues that another person may step in and absolve them. This introduces a communal element. Others can help out when a person realizes his or her limitations.

Humans want to be like God. They inevitably fail in their aspirations, but they can rely on others in their community to come to their rescue. This is the essential message of the high holy days, perfectly captured in the ancient traditions of annulling our personal and communal vows.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.